We now call it the First World War or World War One. Contemporaries certainly thought it was a world war and called it that. The term “World War” (Weltkrieg) first appeared in Germany in 1914. The French and British referred to the war as “La Grande Guerre” or the “Great War”, but also adopted the term “World War” later in the conflict.

The Germans, seeing themselves pitted against the global empires of Britain and France, felt the world was against them from the outset. From their perspective, the war was of such magnitude that it created a sense of the whole world collapsing – the term World War expressed the scale of fear the conflict unleashed.

After 1945, historians found the term “First World War” appropriate because they saw 1914-1918 as the first of a particular type of international conflict – the world’s first industrialised “total” war – which had been followed by a second industrialised world war of this kind – 1939-1945.

There are certainly arguments that can be made, however, that the titles “First World War” and “World War One” are misleading. The Seven Years War, the mid-18th Century battle for supremacy among Europe’s great powers, and the Napoleonic Wars were also fought across the globe, on multiple continents causing severe disruption to global trade. Moreover, if measured in comparison to World War Two, which saw widespread fighting in China, South-East Asia and the Pacific, then 1914-1918 looks more like a European conflict – the key fronts that would decide the outcome of the war were all in Europe. However, the war was clearly global in reach, whether it was the first to be so or not. In 1914, the key belligerent states brought their empires automatically into war with them. Together the British and French empires spanned much of the globe, including almost all of Africa and Australasia; the Russian land-based empire reached from Siberia in the North to the Caucasus and to Vladivostok in the East. Japan went to war on the side of the Allies in 1914, invading German colonial territory in China. The entry of the Ottoman Empire into the war brought its colonial possessions in the Middle East, from Iraq to Palestine into the conflict. When, later in the war, the United States and also Brazil entered on the side of the Allied powers, joining Canada and Newfoundland which were already at war as part of the British Empire, then the war truly spanned the global continents.

While none of the war’s land battles occurred in the Americas, which some historians have claimed meant that World War One was not as global as the Seven Years war or the Napoleonic Wars (if you include the Anglo-American 1812 conflict), this is to ignore the First World War at sea, which saw engagements off the Coronel and Falkland Islands, as well as the war’s disruption of American shipping across the Atlantic.

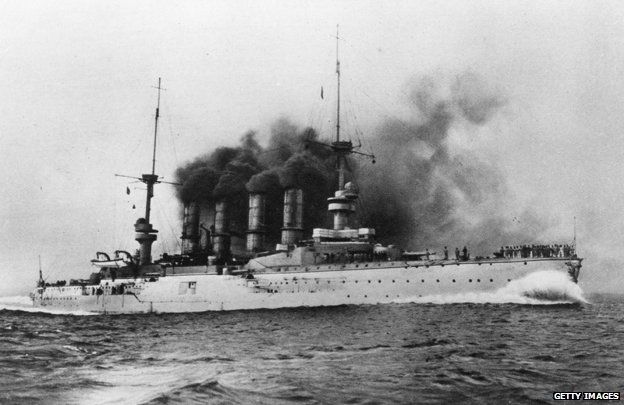

German armoured cruiser SMS Scharnhorst was sunk by the British in action off the Falkland Islands

German armoured cruiser SMS Scharnhorst was sunk by the British in action off the Falkland Islands

And even if there was no front in the Americas, there was fighting almost everywhere else. The opening shot by a member of the British forces in 1914 was fired not in Europe, but in Africa, by a soldier named Alhaji Grunshi serving with the British as they attacked the German colony of Togoland.

The Western Front, which cut through Belgium and Northern France, is well known, reaching, for much of the war, from Dunkirk in the north to Belfort on the Swiss border in the south. But much of the rest of Europe also became a war zone. The Eastern Front, which stretched from the Baltic’s in the north to the borders of Austria-Hungary in the south – with much fighting in what is now modern day Poland, Hungary and Romania – covered a vast swathe of territory; Serbia was harshly occupied. Italy fought on a front that cut across its north eastern border and through the Dolomite mountains, with cities such as Venice threatened by aerial bombardment. Russia fought the Ottoman Empire in a terrible and bloody front that stretched across the Caucasus. As the warring parties sought to break the deadlock the conflict spread even further. The British opened fronts in Gallipoli, at the Dardanelles straits; in Mesopotamia – what is now modern-day Iraq – where after a series of setbacks they ultimately captured Baghdad; and in Palestine, where they fought up from Egypt to capture Jerusalem. In the South Pacific, the Australians fought to capture a series of German colonial island territories, including New Guinea which Australia then occupied for the rest of the war. There was fighting in 1914, as the Japanese captured the German territory of Tsing-tau. In Africa, the Allies (principally Britain, France, Belgium and South Africa) fought to take over the four main German colonies there – German South-West Africa (now Namibia); German East Africa (now Tanzania); the German Cameroons and Togoland (modern-day Togo). Not all of the above fronts existed for the whole of the war, but their span is truly remarkable. An estimated two million Africans served in World War One as soldiers or labourers.

Moreover, beyond each front there was a massive hinterland where normal life was disrupted. Whole agricultural economies were ruined. Civilians starved or fled. In Africa, all of the armies used porters – locals used to carry the soldiers’ food and munitions during the campaign, who were often coerced and who endured terrible conditions and high death rates. The war also gave rise to epic refugee flows in much of Eastern Europe, particularly in Russia, a process aggravated even further by the outbreak of revolution there in 1917. The war saw severe treatment of minorities. In particular, Tsarist Russia persecuted its Jewish population and the Ottoman Empire deliberately destroyed its Armenian minority through massacre and deportation.

World War One was also global in terms of the range of ethnicities and nationalities mobilised to fight. The British mobilised more than a million Indian men for the war. They made up one third of the British army on the Western Front in 1914 – but also fought in East Africa and in Mesopotamia. The French, meanwhile, brought men to Europe from overseas, including Indochina, Madagascar, Senegal, Algeria and Tunisia. The Germans too mobilised black colonial troops but only for use in Africa – Germany believed using non-white troops in Europe was a dangerous breach of colonial racial hierarchies.

Along with fighting men, the British and French also recruited colonial labour on a massive scale, to work on the Western front and in other war theatres. Britain used black South Africans, Egyptians and even military volunteers from the West Indies. Both Britain and France also conducted an enormous recruitment campaign in China bringing some 135,000 Chinese labourers to Europe to do war work. Colonial labourers often found themselves close to the front lines, under fire.

Along with fighting men, the British and French also recruited colonial labour on a massive scale, to work on the Western front and in other war theatres. Britain used black South Africans, Egyptians and even military volunteers from the West Indies. Both Britain and France also conducted an enormous recruitment campaign in China bringing some 135,000 Chinese labourers to Europe to do war work. Colonial labourers often found themselves close to the front lines, under fire.

If we measure the war in terms of its ideological effects it was clearly global. The war’s economic legacy changed the world as the capital of finance shifted during the conflict from London to New York and, with vast swathes of European agriculture ruined, Argentina and Canada greatly increased their market share as food suppliers.

Global attitudes were also changed. The Japanese called for a clause on the equality of all races to be inserted into the League of Nations covenant after the war – they were unsuccessful, but the idea revealed changing mindsets. The first Pan-African Congress, held in Paris in 1919, advocated that African peoples should govern themselves. The war’s legacy was new global ideas about the right of peoples to self-determination and the need for a global system of international co-operation, which was embodied in the League of Nations. It was a war that utterly altered the world and in this regard, in the sheer scale of the changes it brought, it was certainly a first.

The Campaigns

More than 60 million soldiers fought in the armies of the different combatant nations. The total number of deaths includes about 10 million military personnel and about 7 million civilians. The Allies lost about 6 million military personnel while the Central Powers lost about 4 million. At least 2 million died from diseases and 6 million went missing, presumed dead. As well as killing 17 million people, the Great War caused another 21 million wounded. Even today communities around the world are still scarred by their legacy of World War One.

The Middle East Campaign

Main article –http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Eastern_theatre_of_World_War_I

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I saw action between 29 October 1914 and 30 October 1918. The combatants were on the one hand, the Ottoman Empire (including Kurds, Persians and some Arab tribes), with some assistance from the other Central Powers, and on the other hand, the British (with the help of the Jews and the majority of the Arabs) and the Russians (with the aid of the Armenians and some Assyrian tribes) from the Allies of World War I. There were five main campaigns: the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, the Mesopotamian Campaign, the Caucasus Campaign, the Persian Campaign, and the Gallipoli Campaign. There were also several minor campaigns: the North African Campaign, Arab Campaign, and South Arabia Campaign.

Allied military losses are placed between 1,000,000 and 1,500,000 which include those killed, wounded, captured or missing. Against this, total Ottoman losses are recorded as being almost as high as 25% of the population, which equates to approximately 5 million out of population of 21 million. Among the 5 million killed, only 771,844 were military casualties, killed in action or who died from other causes. Military casualties therefore only represent 15% of the total casualties, while 85% – slightly more than 4,000,000 (from all millets) – remain unaccounted for. Ottoman statistics analyzed by a Turkish professor, Kamer Kasim from Manchester University, claim that the cumulative percentage was actually 26.9% (1.9% higher than the 25% reported by Western sources) of the population, which stands out among the countries that took part in World War I. This increase of 1.9% is significant, representing a further 399,000 civilians in the total number. Also, one third of the population died in the largely forgotten famine of Mount Lebanon. A devastating confluence of political and environmental factors lead to the deaths of 200,000 men, women and children in the region.

Serbian Campaign

Main article: Serbian Campaign (World War I)

Austria invaded and fought the Serbian army at the Battle of Cer and Battle of Kolubara beginning on 12 August. Over the next two weeks, Austrian attacks were thrown back with heavy losses, which marked the first major Allied victories of the war and dashed Austro-Hungarian hopes of a swift victory. As a result, Austria had to keep sizable forces on the Serbian front, weakening its efforts against Russia. Serbia’s defeat of the Austro-Hungarian invasion of 1914 counts among the major upset victories of the last century. However, Serbia’s losses were enormous. It lost more than 1,100,000 inhabitants during the war (both army and civilian losses), which represented over 27% of its overall population and 60% of its male population. According to estimates by the Yugoslav government (1924) Serbia had lost 265,164 soldiers, or 25% of all mobilized people. By comparison, France lost 16.8%, Germany 15.4%, Russia 11.5%, and Italy 10.3%.

German forces in Belgium and France

At the outbreak of World War I, 80% of the German army (consisting in the West of seven field armies) was deployed in the west according to the plan Aufmarsch II West. However, they were then assigned the operation of the retired deployment plan Aufmarsch I West, also known as the ‘Schlieffen Plan‘. This would march German armies through northern Belgium and into France, in an attempt to encircle the French army and then breach the ‘second defensive area’ of the fortresses of Verdun and Paris and the Marne river.

Aufmarsch I West was one of four deployment plans available to the German General Staff in 1914, each plan favouring but not specifying a certain operation that was well-known to the officers expected to carry it out under their own initiative with minimal oversight. Aufmarsch I West, designed for a one-front war with France, had been retired once it became clear that it was irrelevant to the wars Germany could expect to face; both Russia and Britain were expected to help France and there was no possibility of Italian nor Austro-Hungarian troops being available for operations against France. But despite its unsuitability, and the availability of more sensible and decisive options, it retained a certain allure that the other plans due to its offensive nature and the ‘cult of the offensive’ that held great sway over much pre-war thinking. Accordingly, the Aufmarsch II West deployment was re-purposed to initiate the ‘Schlieffen Plan’ offensive despite the negligible chances of its then-unrealistic goals and the insufficient forces Germany had available.

The plan called for the right flank of the German advance to bypass the French armies (which were concentrated on the Franco-German border, leaving the Belgian border without significant French forces) and move south to Paris. Initially the Germans were successful, particularly in the Battle of the Frontiers (14–24 August). By 12 September, the French, with assistance from the British forces, halted the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September), and pushed the German forces back some 50 km (31 mi). The last days of this battle signified the end of mobile warfarein the west. The French offensive into Southern Alsace, launched on 20 August with the Battle of Mulhouse, had limited success.

The plan called for the right flank of the German advance to bypass the French armies (which were concentrated on the Franco-German border, leaving the Belgian border without significant French forces) and move south to Paris. Initially the Germans were successful, particularly in the Battle of the Frontiers (14–24 August). By 12 September, the French, with assistance from the British forces, halted the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September), and pushed the German forces back some 50 km (31 mi). The last days of this battle signified the end of mobile warfarein the west. The French offensive into Southern Alsace, launched on 20 August with the Battle of Mulhouse, had limited success.

In the east, the Russians invaded with two armies. In response, Germany rapidly moved the 8th field army, from its previous role as reserve for the invasion of France, to East Prussia by rail across the German Empire. This army, led by general Paul von Hindenburg defeated Russia in a series of battles collectively known as the First Battle of Tannenberg (17 August – 2 September). While the Russian invasion failed, it cause the diversion of German troops to the east, allowing the tactical Allied victory at the First Battle of the Marne. This meant that Germany failed to achieve its objective of avoiding a long-two front war. However, the German army had fought its way into a good defensive position inside France and effectively halved France’s supply of coal. It had also killed or permanently crippled 230,000 more French and British troops than it itself had lost. Despite this, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance of a more decisive outcome.

Asia and the Pacific

New Zealand occupied German Samoa (later Western Samoa) on 30 August 1914. On 11 September, the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force landed on the island of Neu Pommern (later New Britain), which formed part of German New Guinea. On 28 October, the German cruiser SMS Emden sank the Russian cruiser Zhemchug in the Battle of Penang. Japan seized Germany’s Micronesian colonies and, after the Siege of Tsingtao, the German coaling port of Qingdao on the Chinese Shandong peninsula. As Vienna refused to withdraw the Austro-Hungarian cruiser SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth from Tsingtao, Japan declared war not only on Germany, but also on Austria-Hungary; the ship participated in the defense of Tsingtao where it was sunk in November 1914. Within a few months, the Allied forces had seized all the German territories in the Pacific; only isolated commerce raiders and a few holdouts in New Guinea remained.

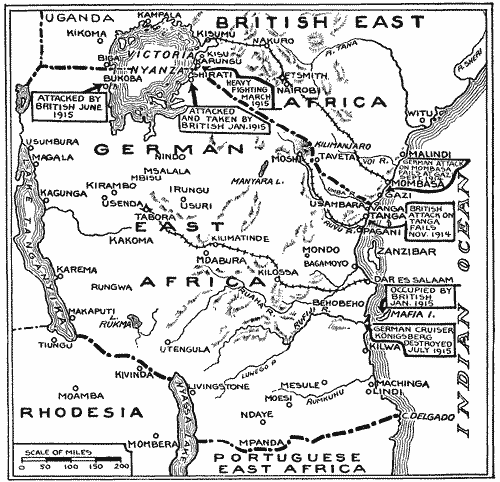

African campaigns

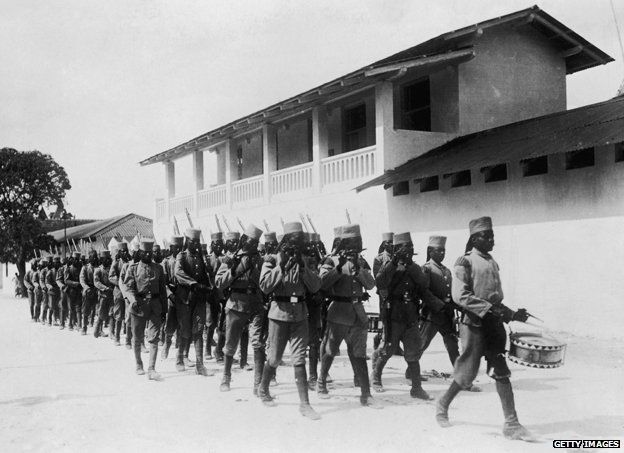

Some of the first clashes of the war involved British, French, and German colonial forces in Africa. On 6–7 August, French and British troops invaded the German protectorate of Togoland and Kamerun.  On 10 August, German forces in South-West Africa attacked South Africa; sporadic and fierce fighting continued for the rest of the war. The German colonial forces in German East Africa, led by Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, fought a guerrilla warfare campaign during World War I and only surrendered two weeks after the armistice took effect in Europe.

On 10 August, German forces in South-West Africa attacked South Africa; sporadic and fierce fighting continued for the rest of the war. The German colonial forces in German East Africa, led by Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, fought a guerrilla warfare campaign during World War I and only surrendered two weeks after the armistice took effect in Europe.

After the war former German colonies were divided between the Allied powers and this ended Europe’s ‘scramble for Africa’. The African campaighns caused an estimate of 350,000 casualties and a death rate of 1:7 people. African found on all sides and were largely coerced into being carriers and porters. They were rarely paid and food and cattle were stolen from civilians. A famine caused by the consequent food shortage and poor rains in 1917, led to another 300,000 civilian deaths in Ruanda, Urundi and German East Africa. The impressment of farm labour in British East Africa, the failure of the rains at the end of 1917 and early 1918, also led to famine. In September 1918, Spanish flu reached sub-Saharan Africa. In British East Africa 160,000–200,000 people died, in South Africa there were 250,000–350,000 deaths and in German East Africa 10–20 % of the population died of famine and disease. In sub-Saharan Africa, between 1,500,000–2,000,000 people died in the epidemic.

Kenya’s forgotten Heroes – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-28836752

Why was the first German Defeat in WW1 in Africa? – http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zck9kqt

The African soldiers dragged into a Europe’s war – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-33329661

Indian support for the Allies

Contrary to British fears of a revolt in India, the outbreak of the war saw an unprecedented outpouring of loyalty and goodwill towards Britain. Indian political leaders from the Indian National Congress and other groups were eager to support the British war effort, since they believed that strong support for the war effort would further the cause of Indian Home Rule. The Indian Army in fact outnumbered the British Army at the beginning of the war. About 1.3 million Indian soldiers and labourers served in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, while the central government and the princely states sent large supplies of food, money, and ammunition. The Indian Army included 800,000 Hindus and 400,000 Muslim soldiers. Over 130,000 Sikh men also served in the war and Sikhs made up 20% of the British Indian Army in action, despite being just 1% of the Indian population at the time. In all, 140,000 men from the Indian Army served on the Western Front and nearly 700,000 in the Middle East. Casualties of Indian soldiers totalled 47,746 killed and 65,126 wounded during World War I. Eight Victoria Cross were awarded to Indian Troops, the first of which was to Khudadad Khan, VC, a Muslim soldier, on the 31st October 1914. The suffering engendered by the war, as well as the failure of the British government to grant self-government to India after the end of hostilities, bred disillusionment and fuelled the campaign for full independence that would be led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and others.

Why the Indian soldiers of WW1 were forgotten – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-33317368

The War at Sea

The ‘Sea Front’ was a global war that lasted the longest. More than two weeks before the first British soldier was killed, some 130 souls were lost on HMS Amphion when it was sunk in the North Sea. The European war was barely 30 hours old. The North Sea was the main theater of the war for surface action. Although safeguarding the English Channel was vital to protect the British Expeditionary Force. The German U-boat campaign in the Atlantic sank much of British merchant shipping causing shortages of food and other necessities. Naval combat also took place in the Meditteranean, the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea and other Oceans throughout the war.

The only full scale confrontation of the war between British and Germans fleets took place on 31st May 1916 and came to be known as the Battle Jutland. Jutland was to be the World’s largest ever naval battle, and proved catastrophic for both sides. The British lost three battle cruisers, three cruisers, eight destroyers and suffered 6,100 casualties while the Germans lost one battleship, one battle cruiser, four cruisers and five destroyers and 2,550 casualties. The outcome of Jutland came as a huge shock to the British Admiralty, as the British fleet had clearly outnumbered German forces (151 to 99). However, Jutland is surprisingly still seen as a victory as it established that Britain had command over the North Sea. Victory would be total. But there was to be no further battle. After four years of naval stalemate, Germany delivered her warships into British hands, without a shot being fired. The date was 21 November 1918. World War One had ended on land 10 days earlier, but this was to be the decisive day of victory at sea. During the course of the war the Royal Navy lost; 2 dreadnoughts, 3 battle cruisers, 11 battleships, 25 cruisers, 54 submarines, 64 destroyers 10 torpedo boats and suffered total casualties of 34,642 dead and 4,510 wounded. Britain’s Merchant Navy also lost 3,305 merchant ships with a total of 17,000 lives.

The only full scale confrontation of the war between British and Germans fleets took place on 31st May 1916 and came to be known as the Battle Jutland. Jutland was to be the World’s largest ever naval battle, and proved catastrophic for both sides. The British lost three battle cruisers, three cruisers, eight destroyers and suffered 6,100 casualties while the Germans lost one battleship, one battle cruiser, four cruisers and five destroyers and 2,550 casualties. The outcome of Jutland came as a huge shock to the British Admiralty, as the British fleet had clearly outnumbered German forces (151 to 99). However, Jutland is surprisingly still seen as a victory as it established that Britain had command over the North Sea. Victory would be total. But there was to be no further battle. After four years of naval stalemate, Germany delivered her warships into British hands, without a shot being fired. The date was 21 November 1918. World War One had ended on land 10 days earlier, but this was to be the decisive day of victory at sea. During the course of the war the Royal Navy lost; 2 dreadnoughts, 3 battle cruisers, 11 battleships, 25 cruisers, 54 submarines, 64 destroyers 10 torpedo boats and suffered total casualties of 34,642 dead and 4,510 wounded. Britain’s Merchant Navy also lost 3,305 merchant ships with a total of 17,000 lives.

Naval Blockades

The British, with their overwhelming sea power, established a naval blockade of Germany immediately on the outbreak of war in August 1914. A blockade was a useful weapon to undermine German trade and keep the powerful German Navy in port. The British blockade lasted until July 1919 and was unusually restrictive in that even foodstuffs were considered “contraband of war”. The Northern Patrol and Dover Patrol closed off access to the North Sea and the English Channel respectively.

The Germans regarded this as a blatant attempt to starve the German people into submission and retaliated with unrestricted submarine warfare on Allied shipping.The blockade also had a detrimental effect on the U.S. economy which wished to profit from wartime trade with both sides, Eventually, Germany′s submarine campaign and the subsequent sinking of the RMS Lusitania and other civilian vessels with Americans on board, turned U.S. opinion against Germany.

It is widely accepted that the British Naval blockade made a large contribution to the outcome of the war. By 1915, Germany′s imports had fallen by 55% from their prewar levels and the exports were 53% of what they were in 1914. Apart from leading to shortages in vital raw materials such as coal and non-ferrous metals, the blockade also deprived Germany of supplies of fertiliser that were vital to agriculture. This latter led to staples, such as grain, potatoes, meat, and dairy products becoming very scarce. These food shortages caused looting and riots, not only in Germany, but also in Vienna and Budapest. The food shortages got so bad that Austria-Hungary hijacked ships on the Danube that were meant to deliver food to Germany. It is estimated that between 424,000 to 763,000 civilians died of malnutrition and disease deaths due to the blockade of Germany. The restrictions on food imports were not lifted until the 12th July 1919 when Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles.

Casualties

Over 1.1 million British and Commonwealth troops died, during World War 1. They are buried in over 23,300 cemeteries in more than 150 countries. Their graves are maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), which replaces 6000 of the 1.1 million individual headstones every year.

Six unexpected WW1 Battlefields http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-30098000

29 June 2014 on the Global war -WW1:Was it really the first World War?. Also Wikipedia for the Campaign information and Getty Images for the photographs. Reproduced here.