Hull officially lost 7,000 men in the First World War. Another 14,000 were wounded, of which 7,000 were maimed. The Hull casualty rate was officially 30% of those who served, that is 21,000 men killed or wounded, from a total of 70,000 men recruited. These were the figures reported by Hull Lord Mayor, in 1919, after the war.

When the foundation stone of the Hull Cenotaph was laid, on the 9th November 1923, the Lord Mayor then, declared that 12,000 people from Hull had died in the war. While this figure can not be verified, it suggests that perhaps, a third or 5,000, of the initial 14,000 wounded, may have already died prematurely, in the four years after the war.

The number of Hull’s war wounded actually increased over time as war injuries worsened and other war related wounds were reported. The Ministry of Pensions, for example, records 20,000 war wounded in Hull, in 1924.

In 1918, Hull covered a larger geographically area than the current city boundary. It encompassed many towns and villages in the East Riding of Yorkshire, which were tied to Hull by travel, work, and family. These included those lost from Beverley (452); Cottingham (105); Hessle (104); Sutton, (36); North Ferriby (24) and Hedon (21). Perhaps the Lord Mayor of Hull was including these casualties, when he declared in 1923, that Hull had lost 12,000 in the war. Few villages escaped the war. Catwick, located outside Hull, is the only “Thankful Village” in East Yorkshire, where, “Thirty men went from Catwick to the Great War and thirty came back, though one left an arm behind.”

Nationally, WW1 casualties were staggering. In the United Kingdom, one in six families, suffered a direct bereavement. 192,000 wives lost their husbands, and nearly 400,000 children had lost their fathers. A further 500,000 children had lost one of more of their siblings. Appallingly, one in eight wives died within a year of receiving news of their husband’s death.

Research from this website reveals that the number of Hull related war deaths was at least 9,984. The ‘Kingston Upon Hull Memorial’, is a data base, that can analyse these casualties, by name, rank, regiment, age, or street. Casualties can also be cross referenced by postcode, and date of death, to key dates in the war, to reveal how events impacted casualties on different areas, over time.

While it is not known exactly who and how the Hull Corporation compiled the city’s 7,000 war casualties, Council records at the Hull History Centre, reveal casualty figures were periodically reported, indicating that the counting began early and a running total was kept during the war. As Hull was geographical larger city, It is remarkable that the Council compiled so many casualties. For many reasons, names of the dead, were easily “lost” in the official reporting. People changed address and moved around frequently. Soldiers enlisted in different towns, under different names, transferred to different regiments, which would have confused the local connection. Discharged servicemen suffered from many war aggravated ailments and diseases, like dysentery, Trench foot, Trench fever, Gas Poisoning, Tuberculosis and Influenza. They were subjected to undiagnosed stresses and strains like “Shell shock”, prone to excess drinking, smoking, and venereal diseases, which contributed to early mortality, but may not have been counted as direct war deaths.

The way names for local memorials were collected, also limited accurate reporting. For example, Hull’s “Golden Book” at Hull Minster, contains only 2,400 Hull casualties. It was compiled through a newspaper advertisement, which required readers to submit a completed form, with a paid subscription. As people were poorer, did not always read newspapers, or have the money for subscriptions, casualties were understandably under reported. Similarly the names for street memorials were collected by well meaning individuals, knocking on neighbourhood doors. However, this may have excluded those who were not in, or unable to respond, or whose families had since left the area. Similarly, single men, with no next of kin, may not have had anyone to remember them. Records were also complicated by the hand written, clerical errors, of the time. Casualty names were sometimes miss spelt, duplicated, or lost in translation. War pension records show many transposed Service numbers, misspelt street names, or addresses of relatives who had moved away from the city, after the war. The people who compiled the Hull casualty figures, could not have known all the Hull men that died, living “outside the city,” serving other countries abroad or who died after being discharged from service during and after the war.

Even the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), which dedicates itself to remembering the Nation’s war dead, omits many Hull servicemen, who were discharged from the service, and died “out of uniform”. Yet Hull Cemeteries, reveal many names of men who died prematurely young, with inscriptions like “Died of shock”, “gas wounds” “after war service” etc. Similarly, local newspapers report many local casualties that do not appear in official CWGC records, even though other records confirm that they served and war pensions were awarded.

This “Kingston-Upon-Hull Memorial” with the benefit of on-line records and multi media sources, aims to remember all of Hull’s losses during the First World War. The 9,984 names recorded here reflect the wider Hull area at the time. It includes, 1,117 men from the East Riding that would have enlisted in Hull or included the city on their postal address. It also includes, 250 men from other parts of Yorkshire, 208 men from Lincolnshire, 86 Londoners, 84 men from other parts of England, 21 men from Scotland, 24 from Wales, 17 from Ireland and 30 men from Australia, Canada and New Zealand, that had a Hull connection, either by birth, work or residency. It also remembers seaman, from all around the world, that were lost on Hull ships during the war. This website can analyse losses in a variety of ways. It reveals that on average,

15 Hull servicemen, were killed and wounded every day during the First World War. Some days were worse than others.

115 Hull men, died on the 1st July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme;

241 Hull men died on the 13th November 1916, (the Hull Pals attacked Serre, at the Somme):

131 Hull men died on the 3rd May 1917, (the Hull Pals attacked Oppy Wood, near Arras):

77 Hull men died on 9th April 1917, serving with the 1st East Yorkshire Battalion, on the first day of the Arras offensive:

157 Hull men, died between the 21st and 23rd March 1918, during the Great German Offensive.

These casualties accelerated as the war progressed, with most Hull men killed in 1918. The 329 Hull men killed in 1914, increased to 1,266, lost in 1915, 2,450 in 1916, 2,593 in 1917 and 2,711 deaths in 1918. Another 298 Hull servicemen died in 1919, being killed in Russia, succumbing to war wounds or the Influenza Pandemic. This was consistent with the rest of country. Britain lost more men in 1918, the year of victory, than in any other year of the war, and more British soldiers were killed in 1918, than the entire Second World War.

As war injuries worsened, so did the death toll. War pension records show that 107 former Hull servicemen died in 1920, 105 in 1921, 26 in 1922 and another 19 in 1924. As war pensions were difficult to obtain, and not everyone applied, the losses could be much higher.

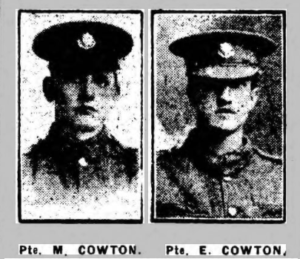

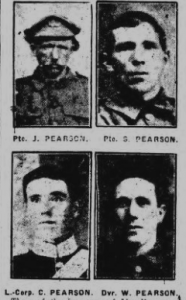

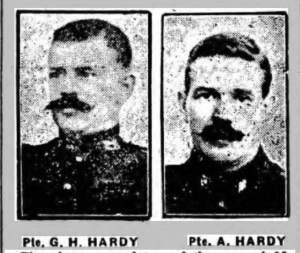

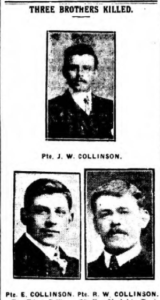

There were over a hundred families in Hull that lost two or more from the same family and at least ten Hull families that lost three sons. Four Hull families are known to have lost four sons. When other relatives are added, such as fathers, husbands, uncles, brothers in laws, cousins and grooms, the losses in some Hull families were immense and tragic.

This website reveals how Hull Communities were devastated by WW1. Twenty six Streets, in Hull, lost 50 men or more, during the WW1. Some of these, were Bean Street (122 men); Waterloo Street (99); Spyvee Street (79); Nornabell Street (75); Gillett Street (72); Walker Street (69), Wassand Street (69); Walcott Street (68); Barnsley Street (67); Courtney Street (65); Buckingham Street (63); St. Paul’s Street (59); Sculcoates Lane (57); New George Street (57); Clarendon Street (54); and hundreds more men died from surrounding streets along Hessle Road, Newland Avenue, Holderness Road, Beverley Road, Anlaby Road and throughout Witham and Wincolmlee, Hull’s industrial area. It is difficult to quantify the social and demographic impact of this great loss of men on the city. Those that lived through it are now gone. Newspapers can only hint of the suffering, with stories of suicides and families left heirless, penniless, orphaned, and homeless.

Hull men from East Yorkshire, served across all armed forces worldwide. Hull men are buried at 961 cemeteries across the globe. Many have no known grave. The National War Memorials to the missing, at Thiepval, on the Somme, lists at least 784 missing “Hull men”; the Ypres, Menin Gate Memorial, records another 485; the Tyne Cot memorial, Belgium, records another 315 and 830 sailors from Hull ships, are recorded on the Tower Hill Naval Memorial, London.

The casualties were mainly Privates, Non Commissioned Officers or from other lower ranks. There are less than 250 Officers listed on the ‘Hull Memorial’, which records 10.238 names of ‘local’ men killed in the First World War.

The first Hull casualty was Thomas Pearson Taylor, accidentally killed on 21/08/1914. The first Hull man to die in action, was Frederick Mileham, killed on 24/08/1914.

The oldest to die were two sailors, both aged 67. The Youngest were three boys, each aged 14 and killed on active service. The majority of Hull’s losses were young men, with 67% dying, aged 30 years or younger. This includes 1,249 Hull Teenagers, of which, 95 died, aged Seventeen, 45, were aged Sixteen, and 9 were aged Fifteen years old.

Hull men fought from the very start of the war, until its end. They served in the all major battles – the Marne, Gallipoli, Jutland, the Somme, Arras and Passchendaele. They fought in the Middle East, East Africa, the Western Front, Salonika and Russia, on land, sea and air.

The war at sea was the longest war and probably the most harshest. Hull sailors fought countless battles daily, mine sweeping, fishing and delivering vital war materials.

Hull trawlers were being lost to stray sea mines, long after the war ended. This Hull Memorial shows at least 1,175 Hull sailors, died at sea.

Hundreds of Hull men were decorated for bravery. Two Victoria Crosses were awarded, first to Private Jack Cunningham, on 13/11/1916 and then to Second Lieutenant, Jack Harrison, on 03/05/1917, both were “Hull Pals”, serving with the East Yorkshire Regiment.

-

The Hull Daily Mail published many photographs of the fallen, particularly during 1914 and 1915. The number of pictures printed declined as the war went on. Below are some Hull Brothers reported killed in WW1.

HULL News. In the early months of the war, there was a trade in soldier letters back home. Many of these were printed, in full, by local newspapers, often giving a graphic insight into the fighting. They reported death, the effects of shelling, the mud, cold and the deprivations of trench life. These publications became heavily censored after 1915.

Hindsight now reveals how local newspapers, often under reported grim news and spread out casualties, over time, to conceal the catastrophe. Mounting losses were often reported months after the event, pushed to the back pages, and mixed up with casualties from other towns, to dilute the impact. War deaths were also hidden between patriotic tales, good news stories of recovering wounded and the announcement of gallantry awards. These seemed to lighten the mood and soften the blow. However, news from returning soldiers, the sight of discharged wounded servicemen on street corners and the rush of over worked “Telegram Boys”, would constantly remind civilians of the brutality of war. The memoriam section on the back pages of the papers, provide many moving verses and poems to the fallen. These highlight the heart felt pain of bereaved friends, families and relatives. On the first anniversary on the Battle of the Serre, the Hull Daily Mail, printed many sorrowful messages, under the heading, “In Proud and undying Memory of the 13th November 1916” (Hull Daily Mail, 13/11/1917, page 3). The charge for a Memoriam Notice was two Shillings and Six pence, for three lines, and Ninepence, for every additional line of seven words. That said, people filled a page with their sentiments. Even a hundred years later, the reader cannot fail to be touched by these personal expressions of remembrance. The impact of war, on Hull, was clearly enormous.

Hull’s four main hospitals and Voluntary Aid Detachment units were constantly busy. Hull was also the main port for repatriated prisoners of war, which added to their work load. Hull cemeteries are littered with servicemen that died in Hull far form home. Those with sight impairments were found work at the ‘Blind Institute’ on Beverley Road. Shell shock victims were treated at De La Pole hospital which also had wards for gas wounds. The Brookland’s hospital, on Cottingham Road, looked after Officers. The Reckitt’s hospital cared for some 3,000 patients during the war. The wounded were very visible in the community. They were often amputees, mutilated, or with appalling facial injuries. Many houses with drawn dark curtains, marked a casualty. It seemed that every family had lost someone, or knew someone that had been killed in the war. Civilians wore dark mourning dress, or black arm bands, to indicate that they were morning the loss of a loved one.

Men physically and mentally broken, or young men who had sacrificed their apprenticeships to go to war, now faced unemployment at home. Rationing of food and basic goods added to the community tension. There were no psychologists or social workers, to treat the victims of shell shock or counsel the large numbers of bereaved. Many families had to cope as best they could.

Newspapers of the time, are full of incidents of violence, drunkenness and anti social behaviour. This reflected the general, poverty, illness and the untreated madness or war casualties. Initial enthusiasm for the war quickly gave way to sadness and shock and a deepening psychological affect on the civilian population. Returning Servicemen had been assured a ‘Land Fit for Heroes’, only to find unemployment, austerity and indifference. Women who lost their husbands in the First World War were granted the first State-funded, non-contributory pension (meaning that they did not have to pay a contribution towards it). They also received a dependent’s allowance for any children under 16. Charities such as “The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association” and “The British Legion” provided some families with additional support. Hull created it’s own unique “Great War Civic Trust“, to specifically help Hull’s many wounded and bereaved families. Not all women were granted the pension. A woman who married an ex-soldier after he had been discharged from the army would not get a pension if he later died from war wounds. Some women had their pensions withdrawn by the Local Pensions Office if they were judged to be behaving in the wrong way, for instance if they were accused of drunkenness, neglecting their children, living out of wedlock with another man or had an illegitimate child. Thousands of women wrote to the authorities to appeal for a pension. There was fear that if the pension was too generous, then it would mean that women would be discouraged from supporting themselves. ‘Eighteen shillings a week and no husband were heaven to women who, once industrious and poor were now wealthy and idle’ one man wrote to the Daily Express, complaining of the pension.

Even after the war, men continued to die from war wounds, accidents and disease, such as the “Spanish Flu”. Hull cemeteries contain many CWGC graves that show that these deaths continued into the early 1920’s. The Ministry of Pensions records 20,000 war wounded in Hull in 1924, so those who died of wounds as a direct result of the war, may well have continued for decades.

Another ongoing peril was unexploded sea mines which continued to take the lives of Hull fisherman, long after the war had ended. For example, the Hull Trawler, ‘Gitano’, struck a mine on the 23rd December 1918, and was sunk with all hands . The Hull Trawler ’Scotland’, struck a mine on the 13th March 1919, killing seven Hull men. Two days later the steam ship, ‘Durban’ exploded‘, killing another eight Hull sailors. The ‘Isle of Man’ (Hull), exploded on the 14th December 1919, killing a further seven Hull fishermen. The steam ship, ‘Barbados’ exploded on the 5th November 1920, taking ten Hull men. These included the two Weaver brothers killed on the same day. Many of these seaman had survived the war, only to be its victims after.

In order to maintain spirits and social order, newspapers released casualty figures sparingly and usually many months after they happened. Patterns of behaviour also changed, with people marrying across classes, taking on different types of employment and becoming more militant and questioning of authority. Crime increased after the war and became more brutal and organised, during the tough economic times ahead. Large numbers of wounded and disabled people adapted to a society, where there was only a limited welfare state to support them.

The scale of casualties and sense of loss, were strongly felt by all those who survived the Great War.