The war at sea is one of the lesser researched subjects of world war one. The main focus is usually on the naval battle of Jutland in 1916, or the lesser known sea battles off the Coronel and Falkland Islands in 1914. The sinking of three British cruisers, within an hour and with the loss of 1,400 lives, by the U-21, on 22nd September 1914 gets a mention. Sometimes an incident, such as the execution of Captain Fryatt, for ramming a U Boat makes the headlines. What is less remembered is that the war at sea was fought every day, during the entire war, across all the world’s oceans and how the vital contribution from Britain’s Navy, Merchant Seamen and fishermen, contributed to Britain’s final victory. Keeping Britain supplied, the sea’s safe and the enemy blockaded became the primary tasks of World War 1. Britain was quick to capitalise on its enduring naval supremacy and geographical position, by establishing a trade blockade of Germany and its allies as soon as war began. The Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet patrolled the North Sea, laid mines and cut off access to the Channel. It curtailed the movements of the German High Seas Fleet and prevented merchant ships from supplying Germany with raw materials and food. Defence was a vital strategy, but it was also gruelling, repetitive and unglamorous. The war at sea was a test of nerves and ingenuity. Both sides had to master technologies and ways of fighting unimaginable just a few years earlier. It was a marathon of endurance and persistence, often thankless, but always critically important. It is estimated that some 44,000 British sailors died during the war, half the bodies were never recovered and a fifth died of disease. Many more sailors were badly injured and their war time experiences would haunt them forever. Some 12 million tonnes of shipping and 5,000 ships were sunk by German U Boats. The Germans began the war with only 28 U-Boats. They ended the war with 380, of which 187 were sunk, with the loss of 515 officers and 4894 enlisted men.

Britain’s Royal Navy

In 1914, Britain was a Naval Super power. It controlled over 45% of the world’s merchant fleet and 60% of larger merchant ships over 3,000 registered tons, and much of Britain’s wealth came from this trade. Britain’s trade was supported and protected by the Royal Navy which in 1914 was the most powerful navy in the world. With 82 battleships, 136 cruisers, 142 destroyers, 80 torpedo-boats and 80 submarines, the Royal Navy’s power worldwide, was uncontested, and unbeatable, both by numbers and quality of the ships and crews. The Royal Navy safeguarded Britain’s immense colonial empire, and was a strong symbol of worldwide supremacy. Britain led the industrial revolution and dominated the European and world economy during the 19th century. It was the major innovator in machinery, such as steam engines (for pumps, factories, railway locomotives and steamships), textile equipment, and tool-making. It invented the railway system and built much of the equipment used by other nations. It was also a leader in international and domestic banking, entrepreneurship, and trade. It built a global British Empire, built upon “free trade,” with no tariffs or quotas or restrictions. The powerful Royal Navy protected its global holdings, while its legal system provided a system for resolving disputes inexpensively. The Royal Navy helped win the war by blocking German food imports. From 1916 onwards, many German civilians, especially those in towns and cities, suffered from severe malnutrition and by 1918 had neither the will or energy to continue the war. Food shortages also contributed to the defeat of German armies and their Allies, Austria and Hungary. On 5th August 1914, the Royal Navy blocked Germany’s international trade. 623 German and 101 Austrian merchant ships took refuge in neutral ports, while Britain and its allies seized 675,000 tons of enemy shipping. Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, established a Contraband Committee to control imports into neutral countries that might be destined for Germany. On 5th September 1914, the German submarine U21 sank the first Royal Navy cruiser, HMS Pathfinder. On 20th September, the U-9, sank three cruisers Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy, in rapid succession killing 62 Officers and 1.397 men. On the 4th February 1915, the German Chief of Naval Staff, Hugo Von Pohl (1855-1916) ordered Germany U Boats, to sink all enemy merchant vessels, without warning regardless of safety for passengers and crews. On 31st January 1917, Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare and on 18th March 1917, sank three American merchant ships, without warning and many American lives lost. U-boats sank 800,000 tons of shipping in April 1917 and between may and July 1917 sank 53 merchant ships for every U-boat lost. The Navy’s response was develop a convoy system to protect merchant vessels and employ Q-ships, armed vessels disguised as steamers which ambushed U-boats when they surfaced. of the 62 Q-ship engagements reported by British Naval intelligence, 11 U-boats were sunk.

Britain’s Merchant Navy

During WW1, the Merchant Navy or Mercantile Marine, was the supply service for the Royal Navy. It carried troops, shipped raw materials, delivered armaments and supplies to the armed forces. It transported food to Britain’s home front and coal and iron and other essential goods to keep factories in production. Britain was heavily dependent on food imports. Between 1874-1914, Britain’s population had increased from 32.5 million to 43.9 million people. British farmers grew only 20% of wheat required to make bread and by 1911, only 56% of Britain’s home meat was home produced. Britain was therefore very vulnerable to interruption of food imports and relied heavily on its merchant navy.

In 1914, it is estimated that about a third of Britain’s merchant fleet crews were born overseas. The majority were Asian, but there were also Caribbean, Japanese, West Africans, Chinese and Arabs. These sailors from across the globe, also served in Royal Naval vessels and made a vital contribution to the war effort. Non European sailors were widely known within the service as “Lascars”. About 51,000, or 17.5% served as crews in British Registered ships. They often suffered harsh, dangerous conditions, working in hot, cramped engine rooms, received inferior rations and less pay than white sailors. They also faced hostility and racism and were often denied senior ranks. While they are memorialised in their home countries, their war here, is largely forgotten or ignored.

In August 1915, 84 British Merchant ships and Fishing Vessels were sunk, by April 1917, losses had risen to 210 vessels, with over 1,130 lives lost in that month alone. Despite its wartime contribution, it was not until 2000 that the Merchant Navy was allowed to join the official march past the Cenotaph, although the Merchant Navy’s Red Ensign had been flown on the Whitehall monument since 1919.

During, and following, the war years, the Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society helped over 50,000 sailors, Merchant Navy and Fishermen, by providing clothing, food, accommodation and rail warrants for them to get back home to their loved ones. It also gave financial assistance to the widows, orphans and aged parents for whom the loss of the only breadwinner was devastating.

Britain’s Fishing Navy

In 1914, Britain possessed the World’s largest and most modern fishing fleet. Britain’s fishing industry included a substantial numbers of skilled and seasoned seafarers. Some 100,000 men and boys were employed in regular and part time fishing in the UK, with 49% of fishermen employed at one time or another in Admiralty service. Over the course of the war, 1,467 steam trawlers and 1,502 herring drifters were requisitioned by the Admiralty from British ports for military action and in 1917, a further 300 were formed into a Fishery Reserve to provide armed protection for fleets still fishing for Britain. Approximately, 39,000 fishermen served on these 3,000 vessels, whilst others, already members of the Royal Naval Reserve, joined other branches of the Royal Navy. The role of these fishermen were many and varied. About one quarter were employed in mine sweeping. The remainder in anti submarine patrols, protecting convoys and maintaining Britain’s fish supplies. Skippers, Thomas Crisp and Joseph Watt were two such fishermen, awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry during the war at sea.

In all, Britain lost 2,479 merchant vessels and 14,287 crew during the First World war. It also lost 675 British fishing vessels, 3,338 skippers and ratings and 434 fishermen. The majority had no known grave, but the sea. By the end of the war, fewer than 14,000 fishermen were left fishing from English and Welsh ports, of which 8,000 were above military age and 400 below it, but the fish trade still managed an average of 8 million tons of fish in every year of the war.

Britain’s Royal Naval Reserve

When the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) was first created in 1859, it consisted of up to 30,000 merchant seamen and fisherman who the Navy could call on in times of crisis. Fishing trawlers were strong, sturdy ships, designed to withstand severe weather conditions out at sea, and in 1907 the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet, Admiral Lord Beresford, recognised that trawlers could be used as minesweepers. Sea mines were shown to be an effective menace during the 1904-5 Russian Japanese war and were becoming more developed and sophisticated. His recommendation led to the formation of the Royal Naval Reserve (Trawler Section) in 1910, with approval to mobilise 100 trawlers during any crisis period and enrol 1,000 men to man them. It also introduced a new rank, that of ‘Skipper’ RNR, into the Navy List. By the end of 1911, 53 skippers had joined. In 1912 a further 25 enrolled and the Trawler Section of the Royal Naval Reserve, consisted of 142 trawlers manned by 1,279 personnel. 31 more skippers joined before the war started in August 1914, making a total of 109 skippers. Another 315 more volunteered by the end of the first week in October. By the end of 1915 the Minesweeping Service employed 7,888 officers and men. By the Armistice, the force consisted of 10,000 men, and 726 vessels, which included 412 steam trawlers, 142 drifters, 110 regular naval vessels, most of which were constructed during the war and 52 hired paddle steamers.

The Royal Naval Reserve (Trawler Section): The German cruiser “Konigen Luise“, laid mines off the English Coast on the first day of the war. This endangered shipping of all nations and was contrary to the Second Hague Convention of 1907. On the 19th August 1914, one of these mines sank the light cruiser, HMS Amphion. In response, 94 trawlers were allocated for minesweeping duties, during the first week of the war in 1914. They were dispersed to priority areas, including Cromarty, the Firth of Forth, the Tyne, the Humber, Harwich, Sheerness, Dover, Portsmouth, Portland and Plymouth. They were supplied with mine gear, rifles, uniforms and pay as the first minesweepers. They were commanded by naval officers, some from the retired list, who had received a brief training in minesweeping. Apart from the skipper’s, officers were also required to supplement the handful of crew of the existing minesweeping service. Most of the trained pre-war RNR and RNVR officers had already been called up for service in the Fleet. For the new minesweeping and auxiliary patrol flotillas, officers and civilians were obtained from the Merchant Navy and given temporary commissions in the RNR and RNVR. To bolster naval discipline, various Royal Fleet Reserve and pensioner petty officers were distributed among the vessels.

In August 1914 the Royal Navy began to requisition more trawlers and adapt them for minesweeping duties, fitting them out with heavy guns, machine guns and depth charges. By the end of 1916 the Navy had requisitioned so many trawlers, and the war had such an impact on shipping, that the supply of fish to the UK was severely limited. New trawlers were also built. Between 1914 and 1918, 371 trawlers were built in the Humber shipyards and almost all of them were taken up by the Navy and used as minesweepers, submarine spotters and coastal patrol boats. Men were asked to volunteer for the new service, and many did so. The Humber area provided over 880 vessels and 9,000 men from the fishing industry to support this war effort. After the war, a large number of fishermen remained in naval service in the British Mine Clearance Service, clearing 40,000 square miles of sea. When the service was disbanded at the end of 1919, 26,000 mines had been removed with the loss of six men.

Britain’s Auxiliary Patrol

This was a front line naval defence force, composed of numerous small craft, tasked with minesweeping and anti submarine patrols, initially around the British Isles, but later also in the Mediterranean. By December 1914, 21 areas around the British Isles had been created for the the Auxiliary vessels to patrol, a basic structure which largely remained throughout the war. The Dover Patrol for example protected the busy shipping lanes in the Channel, stopping and searching ships and deploying mined nets in anti submarine activities. A wide variety of vessels were used, including requisitioned fishing vessels, yachts and motor boats. Like the Minesweepers, the Auxiliary patrol was manned by fishermen and included seaman from all over the world. Their tasks were numerous, the main ones being, patrolling and protecting 565 miles of sea lanes to ensure safe passage. They carried few weapons, but escorted convoys on the outer flanks, listening for submarines with specially fitted hydrophone equipment. The main underwater armament used by the first auxiliary patrols was an explosive sweep, a line of gun cotton charges towed with an electric cable and kept at the right depth by a small kite. They would spot enemy aircraft and listen for any U Boat activity near the convoy and if detected drop depth charges. In many instances when a convoy was attacked or torpedoed, vessels would steam off to limit losses. The Auxiliary Patrol would however remain on the scene to pick up survivors, often putting their own vessels in danger of attack. Submarine warfare was usually a very personal and private war. If you were in it you knew all about it – how to keep watch on filthy nights, how to go without sleep, how to bury the dead and how to die bravely without wasting anyone’s time. The war at sea saw the loss of many fine ships and good men. The largest casualties were in the North Sea and East Coast War Channels. The magnitude of protecting British shipping from mines and submarines meant the Auxiliary Patrol expanded from around 80 ready ships in August 1914, to 3,301 vessels by January 1918, 2,736 of these around the British Isles. There were 150 patrol units, consisting of one yacht as leader, 4-6 Trawlers or drifters and several motor boats. To crew these vessels, men came from all over the Empire. Their success can be measured by the German U Boats sunk, the way they made the work of submarines more difficult and by the fact they kept Britain’s vital sea lanes open throughout the war. Demobilisation of the Auxiliary Patrol began on 15th July 1918 and was completed on 30th April 1920.

Hull’s Sea War

As Britain’s third largest port, at the time, Hull played an active part in all aspects of Britain’s sea war. Hull had twelve docks in all and the King George Dock opened in 1914, was Britain’s first electrified port, providing Hull with deep harbours and the most modern facilities. At first the outbreak of war badly affected Hull. Thirteen percent of Hull’s Trade was directly with Germany and this ceased overnight. Many of Hull’s ships were also arrested, or stranded in foreign ports and unable to return home due to German naval patrols. The Government also diverted cargo away from Hull, particularly after the bombing of Scarborough in December 1914 and in May 1915, which affected local coal supplies and employment. While Hull compensated with some increased trade with neutral countries, like Sweden and Holland, this too reduced in February 1917, when Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare on any shipping helping the Allies. Losses to Hull shipowners were also severe. The Wilson Line, Hull’s largest merchant shipping company, had lost 15 of its 79 ships by 1916, and by the end, over 40 of its 84 vessels and some 300 crew members. The tonnage of shipping registered in Hull Ports fell from 230,000 ton in 1913 to 182,000 by 1917. Therefore, from probably it’s most prosperous period in 1914, Hull declined through the First World war, and took decades to recover. With so many Hull people dependent on the docks for work, the war had an immediate impact on livelihoods and acted as an incentive for young men to enlist.

Over 70,000 men enlisted from Hull during the war. However, Hull still continued to contribute to Britain’s war at sea. Hull supplied 300 ships as Minesweepers, 61 of which were sunk. It also lost another 68 Merchant vessels and 9 fishing vessels. In all over 1,500 Merchant seamen, Royal Naval Officers and ratings and Royal Marines died in the war from Hull.

The Thomas Wilson & Sons Shipping Line, which operated 92 vessels in Hull in 1914, lost 56 ships during the war (3 steamers captured, 49 steamers, sunk and another 4 damaged). It also lost 401 crew, including 14 Masters, 31 Officers, 45 Engineers, 311 Ratings. The losses were so devastating that the company sold up in 1916.

While there were lulls in the fighting on land, the war at sea was a daily battle. Every day, in all weathers, sailors patrolled the seas, engaged enemy submarines, cleared mines and supplied the Nation with food and vital war materials. They also successfully blockaded enemy ports. The management of Britain’s food and shipping were as vital, as any military strategy, and was a daily struggle. Keeping Britain fed during the war, against poor harvests, such as in 1916, and unrestricted submarine warfare, in 1917, became a delicate balancing act. Britain was dependent on American supplies, but these had to be paid for and negotiated with America’s, whose neutrality for the first three years of the war, often threatened supplies. Attempts at food self sufficiency in Britain was largely unsuccessful. While more land was brought into agricultural use, there was a shortage of fertilisers and the supply of skilled agricultural labour and food distribution was disrupted by the war. Starvation was averted by the Government, which created the Ministry of Shipping and a Ministry of Food in 1917. This combined to ration scarce goods, and control both food, and prices. The British food system worked. Prices rose, but so did wages. It is estimated that, consumption of the average person in Britain, fell by only 3 percent during the war, and this became sufficient to avoid civil unrest and continue the war effort. German attempts to sink ship were off set by the Convoy system and Britain’s control of the world shipping fleets which enabled it to absorb huge losses. Britain also successfully blockaded the enemy, increasingly depriving Germany of food and supplies, almost to the point of starvation by the end of the war.

Britain’s Mine sweeping war was another heroic struggle that often goes unrecognised. At the beginning of the war, the Germans started laying mines in the North Sea to prevent food supplies reaching British ports. As the war progressed, a new danger came from German submarines. To combat this the Admiralty requisitioned many of the Hull and Grimsby trawlers, for mine sweeping and anti-submarine patrols. These ships were used to control the seaward approaches to major harbours. No one knew these waters better than local fishermen, and the trawler was the ship these fishermen understood and could operate effectively without further instruction. The larger and newer trawlers and also whalers, were converted for anti submarine work and the older and smaller trawlers were converted to minesweepers. New trawler minesweepers were also built by Cook, Welton and Gemmell Ltd of Beverley, and in total, Hull and the Humber supplied 880 vessels and 9,000 men for this work, during the First World War.

Hull’s War at Sea

Due to Hull’s coastal location, many Hull men joined the Navy in all its forms. Hull men served throughout the world, in the Royal Navy, Royal Marines, Royal Naval Reserve, Merchant Service and the Hull Fishing Feet. 14,000 merchant seamen were to die in the war, 4,000 of these sailors died in just 3 months during 1917, when the German U Boat attacks peaked.

As a maritime City, with a long tradition of seafaring, Hull played an important role in Britain’s sea war. Hull at the time was Britain’s third largest post and largest Fishing port. It built ships, repaired submarines and provided large numbers of ships and crews for all the Naval Services. Hull docks teemed with naval activity and the Humber Estuary was one of the busiest waterways in the world. From the outset, the Humber was designated as a protected area and Fort Paull was used as a submarine listening station. Large battle cruisers sailed up and down the Humber and below the water, a fleet of new submarines were also busily engaged in training exercises. Allied submarines regularly visited the Humber ports and took shelter from the North Sea. Sometimes there were major collisions between submarines and surface vessels, like the trawler “Ferriby”, on 13th August 1914 and the Steamer “Earl of Aberdeen”, on 24th November 1914, which led to a public Inquiry.

The Humber ports of Hull, Goole, Immingham and Grimsby, supplied over 880 vessels & 9,000 men from the fishing trade. These patrolled the North Sea, brought in vital food supplies and swept the sea lanes of enemy mines and other hazards to trade. They collected sophisticated German Sea mines and hauled these back to port, so that British intelligence could learn improvements. They would also collect floating torpedoes for scrap. Life at sea could be full of perils and dangers: submarines, mines, ice, storms, blizzards, hurricanes, ice-bergs, frost, fog, collisions, stranded ashore, wrecked on rocks, and, most of all, fatigue from the endless work in dangerous conditions. Nearly, 1,200 Hull sailors died during the First World war. Many others were wounded, survived sinking, and were emotionally scarred by their war time experiences.

Coastal Defences

In 1913 defence priorities for the Humber were identified and a Defence Plan was finalised just before the out break of war. Kingston Upon Hull, Immingham Docks, The North Killingholme Fuel Depot were all identified as strategic targets. There also many chemical plants, foundries, iron works and factories important to the war effort. Hull Docks, ship yards, saw mills, timber yards, oil depots, and railways were a tempting target. Several coastal guns were established to protect these facilities. The Humber Estuary was protected by gun batteries at Haile Sand Fort, Bull Sand Fort and Spurn Head. A defensive boom was constructed across the Humber from Sunk Island to Killingholme. This was guarded by HMS Albion, a former battleship.

Early in WW1, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was tasked with defending land and sea based targets against both submarine and air attacks. It established a base next to the Admiralty Fuel Depot, which became RNAS Killingholme. The East coast made the area vulnerable to attack and the Humber Estuary was a major navigational aid to bombers. This was shown when Zeppelin airships bombed Hull and the surrounding area several times between 1915 -1918. In response to these raids, Anti Aircraft guns were positioned in Hull. Airfields operated by the Royal Flying Corps were also established. Home Defence Squadron No:36 was based around Kingston Upon Hull to counter the threats of bombing raids. A Relief Landing Ground for this squadron was located at New Holland. The Anti Aircraft batteries included 12 pounders, 6 pound Hotchkiss, 6 ponder Nordenfeldt, 1 pound Naval carriage, 1 pound travelling carriage and 3 inch guns. They were located at Marfleet, New Holland, Chase Hill Farm, North Killingholme and another in North Killingholme itself. Arial bombing began in the First World War and for the first time, people had to adjust to these new defences and the psychological threats of air raids and invasion.

Losses along the Humber

In total, 670 fishing vessels, were lost from the Humberside region, of which 214 were minesweepers. Hull lost 129, of these ships, including 61 minesweepers. ‘Spurn’ Point at the mouth of the Humber is surrounded by 370 wrecks lost in the First World war. Like the ‘Pals’ battalions at the front, the loss of a ship’s crew could have a similar, sudden impact on the tight knit sea communities at home. On average half the crew of a minesweeper were lost when it was sunk. Sometimes the ship casualties were worse, including the loss of the entire crews, and included old men and grandfathers, who had vital sea experience, as well as younger spare hands and teenage cabin crew, who were required to carry out the exhaustive duties of running a ship. For example, the steam trawler ‘Egret’, which was sunk, while on patrol, without warning, on 1st June 1918, lost all eleven crew, including the Master, aged between 21 and 54 years old. Ten of these men were from the Hessle Road area, killed on the same day, while protecting the Humber. Their details are below:

CREW LOST ON EGRET (H21), sunk by the enemy, 2 miles E. x N. Humber, 1st June, 1918.

- CROWE, E (41), 53 Glasgow street, Hull. Cook

- FISHER, George (54), 3 Laura-grove, Tyne street, Hull. 2nd/Hand

- FRANCIS, Septimus (23), 9 Granville-ave, West Dock street, Hull. Deckhand

- McFEE, William (54), 75 Ena street, Boulevard, Hull. Skipper

- MEARS, Alfred (22), 3 Fern-grove, Harrow street, Hull. 3rd/Hand

- RIDSDILL, William (27), 6 Cedar-grove, Eastbourne street, Hull. Chief Engineer

- ROBERTS, Clarence (21), 5 Louisa-ter, St. George’s road, Hull. Trimmer

- SANDERSON, William (60), 8 Naburn street, Hull. 2nd/Engineer

- SMITH, William (43), 8 Langdale-crescent, Flinton street, Hull. Bosun

- TUTCHER, John (50), 2 Chiltern-villas, Division road, Hull. Sparehand

-

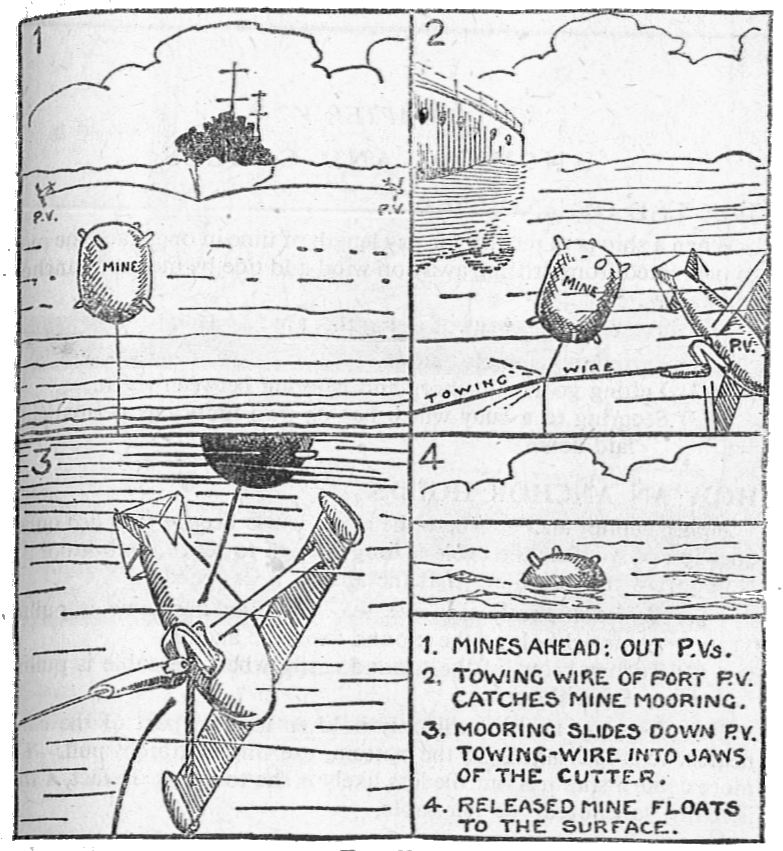

Hull Spring Bank War Orphans. The Orphanage was founded in 1863. Accommodated 210 children with preference for seaman children. Hull Daily Mail 27.07.1916 - During the First World War, 300 Hull ships were used as minesweepers and for searching submarines. 61 of these Hull ships were lost during the war. Fishermen were seen as the best people for the job, as their ships were ideal for this task, they knew the waters well and they could not continue fishing anyway. Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) trawlermen working on minesweepers, were known as ‘Harry Tate’s Navy’, and their rough and ready ways often clashed with the strict discipline and spit and polish of the regular Royal Navy. However, naval officers and ratings soon came to respect the trawlermen’s seamanship, courage and skill at handling the minesweeping gear. They swept an area one mile wide and a 540 miles in length from Dover to the Firth of Forth. This was known as the ‘War Channel’ and all shipping and convoys moved through this channel, which was swept of mines daily. The most effective method for minesweeping was the use of a serrated wire towed by two ships. This would cut through the mooring cable of submerged mines, either exploding them, or allowing the mine to rise to the surface, where it could be exploded by rifle fire. During the war, the Germans laid 1,360 minefields, containing 25,000 mines in British waters. These mines accounted for 46 Royal Navy warships, 269 merchant ships and 63 fishing vessels, which in total, amounted to over 1 million tonnes of allied shipping sunk.

Captain, Albert Thundercliffe, of 90 Waverley Street, Hull and the Hull crew members, of the HMT ‘Ermine’

Only 93 Hull trawlers were used for fishing during the war, and all fish & chips shops were closed in Hull throughout the war. The vessels which remained fishing, were usually old ships that had not been requisitioned by the Royal Navy. The were usually crewed by old men and young boys, unable to serve their country. Nevertheless, these men and boys took similar risks to the many warships. They sailed their unarmed vessels into a mine infested sea, knowing that at any time a U Boat could sink them. They were also prime targets for the German Air force, or Zeppelins that headed to the North Sea fishing Grounds, for easy prey. As the losses to the fishing fleet increased, further restrictions on vessel movements, made fish scarcer and demand could not be met. The rising price of fish was due to this shortage in supply. Prices increased so dramatically, that vessels which averaged a profit of between £6,000 and £7,000 a year before 1914, were by 1917, averaging profits between £30,000 and £40,000. Many of these profits went to the ship owners, rather than the crews. It also enabled the owners to build 40 new fishing vessels during the war, at the Earles shipyard in Hull. Other local firms built another 35 fishing ships during the war. This was a remarkable effort at a time when there was a shortage of skilled labour and materials.

Nine fishing trawlers from Hull were lost by mines, although others which were listed as missing may have met the same fate. The first Hull vessel sunk by a mine was the ‘IMPERIALIST H250’, on the 6th September 1914, 40 miles ‘ENE’ of Tynemouth.

Hull’s first Auxillary patrol vessel lost, was the HMT ‘COLUMBIA’. She was attacked by E Boats off Forness, on the 1st May 1915, with only one survivor.

Submarine Warfare. A far greater threat than the mine, and the largest number of losses, were due to submarine gunfire. A German submarine would surface close to the fishing fleet and in most cases at the beginning of the war, would take the crews off several trawlers and place them aboard another vessel to take them back to port. The unmanned vessels would then be sunk by shell fire from the submarine or a bomb placed aboard. The first Hull vessel sunk by a German U-Boat was the ‘MERCURY H518’ on the 2nd May 1915. This was to change when armed escorts were sent with the fishing vessels and the vessels themselves carried guns, Hull ships then became a target like any other warship and were sunk without warning. In several cases the crews were taken prisoner and were interned in POW camps.

On 3rd May 1915, eight Hull Vessels were sunk by submarine while fishing in the same area of the North Sea. These were the, ‘BOB WHITE H290’, ‘COQUET H831’, ‘HECTOR H896’, ‘HERO H886’, ‘IOLANTHE H328’, ‘MERRIE ISLINGTON H183’, ‘NORTHWARD HO H455′, and ‘PROGRESS H475’.

Hull lost 68 fishing vessels during the WW1. These were vessels that were not on Admiralty service, and not in the Fishery Reserve. Seven of these vessels were lost due to collision or grounding and were not a consequence of war, and 11 were listed as missing of which the cause was unknown. They may have been sunk by enemy action and unclaimed, or most likely contacted drifting mines or entered an unknown mined area. Of the remainder, 4 were sunk by Torpedo Boats. 19 ships where sunk by submarine gunfire and 13 had bombs placed aboard by submarine crew. There were also several other vessels sunk after this period due to mine contact. Another 5 vessels were lost while in the Fishery Reserve. (For the full list see the following link)

http://www.hulltrawler.net/History/WW1/Lost%20Fishing.htm

Hull lost 61 Minesweeping trawlers on Admiralty service during the war. On average half the crew of a minesweeper were lost with the ship. By the end of the War, only 91 Hull owned ships were afloat, 9 of which had been built during the war. Hull lost nearly 1,200 Merchant crewmen, another 267 Royal Navy sailors and 38 Royal Marines. The majority of these died at sea and have no known grave. To add to the tragedy, there was little compensation for a sailor’s family. A sailor’s pay stopped when their ship sank, and they were usually only paid if they died with the ship. Sailors who left their ship in life boats were deemed to have discharged themselves from duty and often had their sea pay docked.

At the end of the First World War, Lord Jellico declared that the Royal Navy had saved the Empire, but it was the fishermen in their boats who had saved the Royal Navy. The Royal Naval Reserve of fishermen was “a Navy within the Navy“. They swept mines, escorted convoys, hunted U-boats and carried out countless dangerous duties. While often overlooked by Admiralty officials, their contribution was at least recognized by Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon who said; ‘It is doubtful if we could have defeated the Germans, at any rate as quickly as we did defeat them, if it had not been for the assistance which the Royal Navy received from the fishing community.’

Hull ships and crews therefore played a major part in that victory. The ongoing peril of unexploded sea mines continued to take the lives of Hull fisherman, long after the war had ended. For example, the Hull Trawler ‘Gitano’ struck a mine and was sunk with all hands on the 23rd December 1918. The Hull Trawler ’Scotland’ struck a mine on the 13th March 1919, killing 7 Hull men. Two days later, the steam ship ‘Durban’ exploded‘, killing another eight Hull sailors. The ‘Isle of Man’ (Hull) exploded on the 14th December 1919, killing a further seven Hull fishermen. The steam ship ‘Barbados’ exploded on the 5th November 1920, taking ten Hull men. These included the two Weaver brothers killed on the same day. Many of these seaman had survived the war, only to be its victims after.

Illustrations of life on board a trawler – “In the Wheelhouse, Mail Day, playing cards, cleaning guns, the Galley cook, the stoker, the radio officer, slipping the “kite” which controls the mine sweeping depth.”

.

Early mine sweeps simply comprised of chains towed over the seabed between two ships, or even by a single ship to drag mines and their moorings out of a channel. These were later replaced with serrated wire cables towed between two ships (Actaeon Sweep). Development of the Oropesa Sweep, with its divertors and depth-keeping kite, allowed sweeps to be towed by a single ship. Sweep wires were made from flexible, steel wire rope and streamed from each quarter of a minesweeper. The cables were laid right or left-handed according to the side streamed. This helped the wires achieve hydrodynamic lift and spread. A single strand in each wire was laid in the opposite direction to provide a serrated cutting effect.

The ‘Paravane’, was a form of towed underwater “glider”. It was developed between 1914–16 by Commander Usborne and Lieutenant, C. Dennistoun Burney, and funded by Sir George White, founder of the Bristol Aeroplane Company. Initially developed to destroy naval mines, the paravane would be strung out and streamed alongside the towing ship, normally from the bow.The wings of the paravane would tend to force the body away from the towing ship, placing a lateral tension on the towing wire. If the tow cable, snagged the cable anchoring a mine, then the anchoring cable would be cut, allowing the mine to float to the surface where it could be destroyed by gunfire. If the anchor cable would not part, the mine and the paravane would be brought together and the mine would explode harmlessly against the paravane. The cable could then be retrieved and a replacement paravane fitted. Burney explosive paravanes were deployed from torpedo boat destroyers in a configuration known as the ‘High Speed Sweep’ to counter submarines. However, most paravanes were non-explosive and were streamed by larger warships and merchant ships as self-defence measures to divert moored mines away from their hulls. They comprised a wire streamed to each side from the bows with a float secured to the end to divert it outwards. This is illustrated below.

5 most successful U-boats

The following are the most successful U-boats during WWI, in terms of ships sunk.

| Boat | Ships sunk | Tons sunk | Ships hit during |

| U 35 | 226 ships | 538,500 tons | 1915 – 1918 |

| U 39 | 154 ships | 406,325 tons | 1915 – 1918 |

| U 38 | 139 ships | 293,134 tons | 1915 – 1918 |

| U 34 | 119 ships | 257,652 tons | 1915 – 1918 |

| U 53 | 88 ships | 225,364 tons | 1916 – 1918 |

The most successful U-boat commanders of World War I were Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière (189 merchant vessels and two gunboats with 446,708 tons), followed by Walter Forstmann (149 ships with 391,607 tons), and Max Valentiner (144 ships with 299,482 tons). So far, their records have never been surpassed by anyone in any later conflict.

Post WW1 – Mine Clearing:

At the end of the war, Britain was one of 26 countries represented on an International Mine Clearance Committee, dedicated to clearing 40,000 square miles of sea of leftover mines. Several hundred thousand mines had been laid during the conflict by both sides. Each power was allotted an area to clear. The British Mine Clearance Service was formed in 1919 and worked to clear Britain’s allocated area until it was disbanded the following year. By the time of the Armistice, the Trawler Reserve now consisted of 39,000 officers and men of whom 10,000 were employed in minesweepers and the rest in the auxiliary patrol. The 10 ex-torpedo gunboats available as minesweepers at the outbreak of the war had been replaced by purpose-built ships, including:

ur_collections/source_guides/ships_and_shipping.aspxhttp://www.hullcc.gov.uk/museumcollections/collections/theme.php?irn=158

http://www.mylearning.org/local-heroes-hulls-trawlermen/p-2631/

http://www.hullhistorycentre.org.uk/discover/hull_history_centre/

http://www.naval-history.net/WW1LossesBrFV1914-16.htm

http://www.scarboroughsmaritimeheritage.org.uk/auboatsarthurgodfrey.php

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-30128199

Thank You to “Hull, the Good Old Days” Facebook, for the above photos.