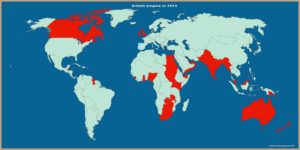

Britain in 1914

Britain at the start of World War One, was a much different place than today. Britain in 1914 ruled the largest empire in history, through industrial might, commercial prowess and maritime supremacy. Britain through its colonies, dominions, protectorates and mandates, controlled about a quarter of the World’s land surface and some 435 million people, or 20% of the world’s population. Half of these people were Hindus. The legal, linguistic and cultural influence of Britain was worldwide and immense.

Britain was then, the wealthiest country in the world and had the largest and most powerful navy. Britain built 50% of the world’s tall ships. Over 40% of the all the world’s merchant fleet flew the British flag. Only Germany produced more than Britain economically. Unchallenged at sea, Britain adopted the role of global policeman. Alongside the formal control it exerted over its own colonies, Britain’s dominant position in world trade meant that it effectively controlled the economies of many countries, such as China, Argentina and Siam. British imperial strength was underpinned by new technologies, like the steamship and telegraph, which allowed it to control and defend the empire.

Britain’s population in 1914 was about 46 million and it was considered very overcrowded. From 1900, one in twenty British citizens emigrated to the colonies for a better life. In 1912, 300,000 people alone migrated from Britain. The majority moved to the United States, Australia and Canada.

Life in Britain could be very poor. About 80% of the British people were ‘working class’ and 90% rented their homes, rather than owned them. One percent of Britain’s richest people owned 70% of the wealth. The average weekly wage was only £1.40. Life expectancy for a wealthy man was 55 years. Most people in poorer parts of Cities were lucky to live beyond 30 years old. Beer was 2p a pint. It was only compulsory to attend school until the age of 12. Many children left school early to work and support their families. Only 6% of children remained at school over the age of 16. Five million women worked, mostly as maids, cooks and servants, but they did not have the vote and there were no female Members of Parliament. Only half of men could vote. The First World War would change Britain.

Europe in 1914

If Britain was the worlds’ Superpower, Europe in 1914 was the most wealthy and powerful continent on earth. While past civilisations might have built great cities, invented gunpowder or algebra, nothing could compare to Europe’s material and technological culture. Europe was integrated more then, than it had ever been, intrinsically linked by flows of goods, money and people. Europe was an engine room of enterprise and innovation, densely interconnected and criss-crossed by railway lines and telegraph wires. Europe represented the summit of interdependence, with each country relying on its neighbours for resources, markets or access to the rest of the world. The GDP of Europe before the First World War was not equalled again until 1970. Empire was Europe’s supreme product. Imperialism expressed National prestige and superiority and was seen as a legitimate way of organising and improving the world. Little thought was given to the exploitation of indigenous people. Even Europe’s smaller nations like Denmark, Portugal, Belgium and the Netherlands, had empires in the Caribbean, south east Asia or central Africa. Only Austria and Hungary had no colonial empire. However, the slaughter and barbarism of the First World war ended Europe’s credibility as a civilising force. Europe had squandered its wealth fighting the war and many of its nations were in debt. The war and the peace that followed, would change and challenge Europe’s dominance. While London and Paris remained the capital cities of the world largest empires, the Versailles Treaty, signalled a new world order of Nation States running affairs, rather than Empires. The German Kaiser would flee to exile in Holland, his empire would become the German Republic. The German capital city would be moved from Berlin to Weimar. The Austrian- Hungarian empire, built up over centuries, would after four years of war, be carved into the new states of Czechoslovakia. Both Austria and Hungary would be reduced in territory. Austria which was almost completely German speaking, would be forbidden from uniting with Germany again. The once grand imperial capital of Vienna would become an oversized capital of a much smaller Austria. In eastern Europe’, Poland re-emerged as a new country. The Balkans became Yugoslavia. Russia wracked by revolution and civil war, became a Soviet Union of states. The Tsar and his family were shot. The Russian capital was moved from Petrograd to Moscow. At the end of the Great war, the Ottoman Empire was dismantled and a new country called Turkey was created. Arab territories fell under the political influence or direct control of Britain and France, with London replacing Constantinople as the ultimate master of Jerusalem. The Great War was the beginning of the end for Europe’s predominance in world affairs, and for its claim to civilisation superiority. The only countries to emerge from the Great war, stronger, richer and more influential, were Japan and the United States.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF)

In 1914, Britain’s Regular Army after mobilisation numbered 460,000. Added to this was the Territorial Force of 240,000, and it could field 700,000 men compared to the Germans 4.5 million.

Under the 1839 Treaty of London, Britain was duty bound to protect Belgium. When Germany invaded Belgium on 4th August 1914, and refused a British ultimatum to withdraw, Britain mobilized the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).The BEF initially consisted of 4 Infantry Divisions and 1 of Cavalry, a total of about 100,000 men and 30,000 Horses. Each Infantry Division had 18,000 men; (12,000 Infantry, in 12 Battalions, in 3 Brigades, each of 4 Battalions. It had 24 machine guns and 76 guns plus Engineers and Medicals. A Pioneer Battalion, which could act as fighting Infantry, would be added. Corps would later have a Cyclist Battalion. A Cavalry Division had 9,000 men, 10,000 horses, 24 machine guns, 24 guns and supporting troops.

To a meticulously planned, pre-war timetable, the BEF arrived in Belgium within 12 days to halt the German advance. This mobilisation of the BEF was phenomenal. One division alone, contained 19,000 men, 5,600 horse, 75 guns, and 650 wagons. It occupied in column, ten miles of road and required 90 trains to transport. Britain transferred 4 divisions in just 12 days, with the 2nd Corps operating near La Bassee and 3rd Corps, based at St Omer, in only the first 3 days. Contrary to popular belief, the BEF were not Britain’s best troops. The majority, were relatively recent enlistments, with a high proportion having less than two years service. The more experienced soldiers, were reservists who had left the army years ago, and their standard of fitness and military knowledge varied considerably. However, the quality of Britain’s military training was good and the majority of its Officers and NCO’s were experienced and battle hardened. The British Battalion system was also an excellent way of bonding troops into an effective fighting force.

The Four Divisions of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), sent to France in 1914, numbered approximately 100,000 men. Although outnumbered by the Germans by at least ten times, the BEF halted the German advance from 23rd August 1914, at Mons, Le Cateau, and then along the River Marne.

These first three weeks of the war were a critical period, in which the German plans to end the war at a stroke were stopped. While the BEF was successful in holding the Germans at bay, much of the Army was destroyed in the fighting. Between 5th August and 30th November 1914, the BEF suffered 86,237 casualties. These represented a large core of the Professional British Army. To replace these numbers and commanders, Britain had to quickly recruit and train New Armies.

The original 4 Infantry Divisions, organised into 2 Corps, one commanded by Haig, had increased by Christmas 1914 to 12, by the Somme to 53, and later to about 63.

Of these Infantry Divisions:

- 13 were Regulars (On mobilisation about 40% were Reservists. Of these 13 Divisions 8 were formed from troops stationed in Britain, and 5 from Empire Garrisons as soon as Territorials could replace them, then add the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division formed from Royal Marines and surplus sailors, and the Guards Division which was formed in 1915, the same year as the Welsh Guards were created.)

- About 19 from the Territorial Force (Pre-war it had 14 Infantry Divisions and 14 Yeomanry Brigades, but it was under strength and under trained. The Territorial Force men were not liable for foreign service, unless they volunteered, or were volunteered. They were deployed in 1915.)

- 30 from the New Armies. (Kitchener, realising that the Army would need massive expansion, decided to raise new Divisions, instead of relying on expanding the Territorial Force. By January 1915, 500,000 volunteers had been formed into 30 Divisions. There were immense problems equipping and training them. There were initially no officers, NCOs nor instructors, let alone weapons. But they were deployed before the Somme. 38% of the New Armies comprised of PALS Battalions. The difference between them and the other New Army Battalions was that they were raised, clothed and equipped by corporations of large cities and were composed of men from a particular area or profession. This allowed them to serve with their friends – as examples: the Stockbrokers Battalion became the 10th Royal Fusiliers, and the North Eastern Railway Battalion became the 17th Northumberland Fusiliers. In one Brigade its 4 Battalions were known as ‘The Hull Commercials’, ‘The Hull Tradesmen’, ‘The Hull Sportsmen’ and for want of a better name ‘The Hull T’others.’ The War Office, which could not provide for all the volunteers, was delighted with this arrangement.)

Plus from the Empire: 2 from India, 4 from Canada, 5 from Australia, 1 from New Zealand, but only a brigade from South Africa, as they were also deployed on their continent. The Indian ones were withdrawn in 1915 and some of the British Divisions were sent to, or brought back from, at various times Italy, Gallipoli, Salonika, Palestine, or Mesopotamia.

Thereafter, the ‘Western Front’ developed into a line of opposing trenches, stretching 460 miles, from the North Sea to Switzerland. There were 25,000 miles of trenches, enough to wrap around the entire planet – front line trenches, reserve and support trenches, connected by communication trenches. This ‘front line’ barely moved for more than two years. Both sides were evenly matched and although they produced deadly new weapons, like tanks, aircraft, and gas attacks, to break the deadlock, these were soon countered, to create a tactical stalemate The civilian population from France and Flanders was evacuated and the occupying forces settled into the long, grinding routine of trench warfare. The Germans were quick to seize the high ground and dug their trenches in deep, taking advantage of the better soil conditions. This gave them a great defensive advantage over the attacking allies.

In the first two weeks of October 1914, the BEF was moved from the central sector of the front to Ypres and Flanders.

This move shortened its lines of communications which ran through Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne. Britain was able to protect these ports which were vital to its own supplies and reinforcements, and to the Royal Navy’s command of the Channel.

The Battle of Neuve Chappell between the 10-13th March 1915, was an indication of things to come. Britain’s Royal Flying Corps was used for the first time to take observation photos of the German defences. This innovation allowed the BEF artillery to accurately target the Germans and blow a six mile hole in the German front line. However, British telephone cables had been broken by the German shell fire and poor communications with the artillery meant that the BEF infantry could not advance until the barrage stopped. This delay allowed the Germans to regroup. When the BEF 1st Army, eventually attacked, the Germans were ready for them. Some 200 German troops from the Jager 11 Battalion, armed with two Maxim machine guns, firing 600 bullets a minute, held 9,000 British and Indian Troops, at bay for 90 minutes. They could not be moved, as the British artillery was running low on shells. A counterattack by the 16,000 Germans was similarly mowed down by machine guns, but pushed the British back to almost where they began. The battle killed 21,000 men, some of the BEF’s best troops (Ten Victoria Crosses were awarded), but achieved tactically nothing It did however expose the futility and costly stalemate of trench warfare,- massive artillery bombardments, followed by calamitous infantry assaults and costly counter attacks, with little gain. A pattern to be repeated across the entire front line, for the next three years.

Over the next four years the BEF’s strength rose to 50 Divisions, and 12 overseas Commonwealth Divisions. This comprised troops from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Newfoundland and the British West Indies.

The British and Commonwealth forces fought a number of bloody battles in the defence of the Ypres salient. Other major battles, like the Somme, Messines, Cambrai, Arras and Passchendaele took place across the entire front line during the course of the war.

In March 1918, following the earlier capitulation of Russia in the East, Germany with over a million extra troops, began their great offensive on the Western Front aiming to finish the war. Their sweeping advances reclaimed all of the ground the Allies had won before. However, by August 1918, the Germans were a spent force. They had lost many of their best troops in the offensive. The pitted battlefields meant their supply lines were overstretched and slow. German troops became hungry, exhausted and disillusioned. While the German offensive had made large advances, their land gains were not strategic, and did not threaten the allied ports and supply lines. Stiff allied resistance, boosted by fresh American troops arriving on the Western Front, eventually halted the German attacks. The Allies then retook the offensive and through August and September 1918, counter attacked across the old battlefields and beyond.

The British Army during the First World War was the largest military force, that Britain had ever put into the field up to that point. Over the course of the war 5,399,563 men served with the BEF, the maximum strength being 2,046,901 men. On the Western Front, the BEF ended the war as the strongest fighting force, more experienced and bigger than the American Army and with better morale than the French Army.

The cost of victory was high. The official “final and corrected” casualty figures for the British Army, including the Territorial Force, were issued on 10 March 1921. The losses for the period between 4 August 1914, and 30 September 1919, included 573,507 “killed in action, died from wounds and died of other causes” and 254,176 missing (minus 154,308 released prisoners), for a net total of 673,375 dead and missing. Casualty figures also indicated that there were 1,643,469 wounded.

Photos: Courtesy of The Imperial War Museum Collection.

For a useful summary of Britain’s BEF and expansion, see the following link: https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/the-contemptible-little-army-1914-1918/