Hull was unusual in that it recruited an entire (Hull) Brigade in the 31st Army Division. This included five ‘Hull Pals’ battalions which were five Infantry Regiments, three Heavy Artillery Batteries and a Divisional Ammunition Column.

After a short spell in Egypt, the Hull Pals, served on the Western Front from 1916 until the end of the war, as did the 2nd and 3rd Hull heavy batteries. Hull also equipped two Volunteer battalions made up of local Golfers, for Coastal Defence, raised its own Army Service Corp in 1915 (the only City to do so) and created Britain’s first Anti-Aircraft Unit, which was raised in Hull, within 14 days.

War Declared on 4th August 1914,

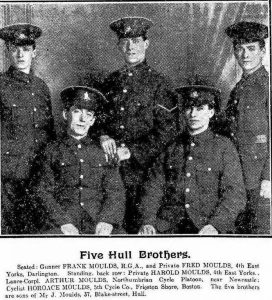

The local Territorial battalions, the 4th and 5th East Yorkshires, and the Territorial Royal Field Artillery were mobilized and reservists received their call up papers. The Hull Daily Mail recorded that about 100 naval reservists left Hull for the South of England on the 5.05am train to London. The sudden loss of men affected the ability to bring in the harvest and hit the fishing fleet and merchant navy very hard.

Hull was the major recruitment centre for the East Yorkshire Regiment, but as it was also a major port, a large percentage of the population were already recruited by the Merchant Navy, the fishing Fleet, the Royal Navy and the Humber Estuary and Coastal Defences. As well as the demands of the sea, there were other units in existence which further drained the supply of Hull men. In the East Riding there was a Yeomanry regiment, two territorial battalions, a Royal Garrison Artillery battery, a Field Ambulance of the Royal Army Medical Corps and a Field Company of the Royal Engineers.

With the onset of war, each of these (except the 5th Battalion) were recruited, firstly up to full strength and then recruited a second line unit to replace the first when it went on active service. The 4th Battalion actually raised a third line battalion. Competition was particularly fierce to join the Hull cyclists, who with their ‘knee britches and black bugle buttons’ were seen as a rather noticeable unit to belong to. Army life meant regular pay (one shilling a day for privates, plus 2 shillings a day if billeted at home). They also received proper food and clothing, not to mention barracks that compared favourably with the living conditions experienced by many at the time. Recruitment was boosted further by the decision to form local units, that became known as “Pals” Battalions.

When voluntary enlistment ended at the end of 1915, Lord Nunburnholme and the East Riding Territorial Association, had been responsible for raising not only the Second and Third Line Territorial units in the county, but the following New Army units:

-

- 11th (1st Hull) Heavy Battery and Ammunition Column, RGA

- 124th (2nd Hull) Heavy Battery and Ammunition Column, RGA

- 146th (3rd Hull) Heavy Battery and Ammunition Column, RGA

- 31st (Hull) Divisional Ammunition Column, Royal Field Artillery

New Recruits for the Hull Commercials, 10th East Yorkshire Regiment - 10th (Service) Bn, East Yorkshire Regiment (1st Hull)

- 11th (Service) Bn, East Yorkshire Regiment (2nd Hull)

- 12th (Service) Bn, East Yorkshire Regiment (3rd Hull)

- 13th (Service) Bn, East Yorkshire Regiment (4th Hull)

- 14th (Reserve) Bn, East Yorkshire Regiment (5th Hull)

The first four “Hull Pal” battalions served in Egypt and France, during the war. The 2nd & 3rd Heavy Batteries and Ammunition Columns, served in France from 1916. The 11th (1st Hull) Heavy Battery had been intended for the 11th (Northern Division), but was left behind for training, when that formation was rushed out to Gallipoli in 1915. Instead, the battery was equipped with obsolescent howitzers and sent to Tanzania, East Africa, where it fought a hard campaign between 1916–17. The East Riding Territorials performed a number of valuable roles home and abroadt The 1st East Riding Yeomanry served in Mesopotamia between 1915-17, protecting oil supplies for the Royal Navy. It was posted to the Western Front, in 1917.

Recruitment Begins

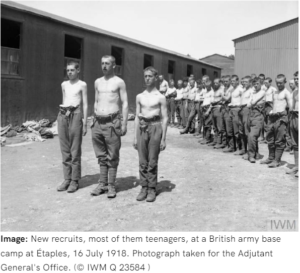

On 6 August, 1914, Parliament sanctioned an increase in Army strength of 500,000 men. Day’s later, Lord Kitchener, The Minister of War, issued his first “Call to Arms”. This was for 100,000 volunteers, aged between 19 and 30, at least 1.6m (5’3″) tall and with a chest size, greater than 86cm (34 inches). Minimum physical standards fluctuated during the war. In the chaos of early 1914, a blind eye was often turned to official standards. Examinations could be brief and hasty, allowing many underage or unfit men to slip through into the Army. One example was Gladstone Simpson, from Barnsley, who enlisted in Hull and joined the 1st King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. He died of wounds, on 10th June 1915, aged just 16 years and 9 months.

While average life expectancy for men had increased to 51 years by 1914, It was an era of childhood illness, inadequate medical care and no antibiotics. Tuberculosis, whooping cough, diphtheria, scarlet fever and measles – associated with poverty and overcrowding – were still rife. Many Hull volunteers were initially rejected on medical grounds, suffering from the cumulative effects of poor diet, medicine and housing. Army medical records show that many men were under weight, and undersized on enlistment. They suffered like many civilians, from a range of physical ailments, such as rheumatism, heart disorders, respiratory problems, defective teeth, ear and eye disease, gastric ulcers, epilepsy and hernias, brought on by strenuous labour and impoverished life styles. Dental health was very poor in the early 20th century – 70 per cent of British recruits were regarded as in need of dental treatment. In 1914 there were only 20 trained dentists in the military. The term ‘trench mouth’ was coined during the First World War, and describes an acute gum infection that involves painful necrotising ulcers throughout the mouth. No dental surgeons were sent to France in 1914, but by 1918, 800 were serving in the army either in the field or at home. The eyesight standard in the British Army in 1914 was the lowest in the European armies – the standard required in the latter being 6/12 with/without glasses (meaning that one can see at a distance of 6 meters what a normal person can see at a distance of 12 meters), whereas it was 6/12 unaided in the British Army. For those who passed the test, King’s Regulations (1704) stated: ‘Glasses may be worn by all ranks on or off duty’.

Medical examinations during recruitment were often rushed and superficial. Doctors were under time pressure and were paid a shilling for every man recruited (and nothing for those rejected). Some recruits were underage and overaged. Many men with pre-existing health conditions were selected and remained on, active service, despite the alleged weeding out. Some recruits, with general weakness or in the language of the day, “Debility” and “Feeble mindedness” remained in the army to do menial tasks. Other soldiers discharged as “unfit”, managed to re-enlist later in the war, often by enlisting in another area with different doctors.

The basic steps to recruitment were to join the queue, pass a series of basic tests, swear allegiance to the King and Country, “against all enemies”, join a Unit (Some new soldiers took on specialist roles if they had a special skills, like being able to drive), go to training camp, and learn military discipline, drill and how to fight with rifle and bayonet. Each soldier carried a message from Lord Kitchener in his pay book, reminding him to be ‘courteous, considerate and kind’ to local people and allied soldiers, and to avoid ‘the temptations both in wine and women’.

Hull was a prime recruitment centre, for new recruits. It’s population of over 300,000, was considerably higher than today and the surplus of available manpower enabled Hull to recruit its own Army Division. There were many men living and working Hull who were not born in the City. This is revealed in the WW1 Soldiers Died records which gives the hometowns of those that enlisted. About a third of those who enlisted in Hull were born outside the city. There were many reasons for this diverse population. Hull had monopolized the sea passenger service from Europe to America and over two million European Immigrants had travelled through Hull to the “New World”. Some of these migrants had stayed in the City and established themselves. Hull’s pork butchers for example, originated largely from Germany and were Naturalised British Citizens. Similarly, Hull had a large, vibrant Jewish community, with 26 Synagogues in the City. In keeping with the patriotic mood of the time, these emigrants were keen to serve their new country. The 1851 Census also shows that many people from Ireland and Lancashire had settled in Hull in the 1880’s when the City’s fledgling textile industry, began. These were now of prime recruitment age. Hull was also a busy, bustling port, which attracted sailors and workers from all round the world to crew ships and work on the Hull docks. An analysis of Soldiers Died records between 1914-1919, shows that that from the 6,569 men who enlisted in Hull and died in the war, 4,409 (67%) were born in Hull and 3,056 (46%) of these joined the East Yorkshire Regiment. Those who enlisted in Hull and died, included 65 men born in London, 24 men born in Ireland, 12 from Wales, 24 from Scotland, 8 Canadians, 3 Australians,4 men born in India, 3 South Africans and a man born in Cairo,Egypt. Hundreds of men from the outlying villages of East Riding and Yorkshire, also enlisted in Hull as well as men born in Liverpool, Leeds, Durham, Newcastle, Blackburn, Bolton and other major towns. Some of these men, included, Lawrence King, born in Moosejaw, Manitoba, Canada and Joseph Edward Manseau, from St. Phlix-de-bolis, Canada, who both enlisted in Hull and were killed serving the Machine Gun Corps. Also Alfred Anthony Clegg, a Londoner, who lived in Ontario, Canada, who joined the 11th King’s Royal Rifle Corps in Hull and was killed on 20th November 1917. Similarly, Samuel Draffin, born in Kirkestown, County Tyrone, who enlisted in Hull, and joined the Royal Irish Fusiliers and Ingvald Orthininssen, born in Argentina, who joined the 15th Durham Light Infantry, from Hull. Kay Ditlevsen, from Copenhagen, who died with the Army Service Corps. These were soldiers who died and enlisted in Hull. They do not include the many other Hull born men who enlisted elsewhere and abroad, or the Hull sailors who served in the Royal Navy, Auxiliary Fleets and Merchant Navy.

Hull was a railway hub which also drew in manpower. The Hull and Barnsley Railway line, built in 1883, connected Hull to outlying villages like Swanland, Willerby and Kirkella, providing easy travel for men wanting to enlist in Hull. Similarly, the North Eastern Railway Line which monopolized transport also drew recruits into the City. This can be seen by Hull forming its own Railway Pals battalion, the 17th Northumberland Fusiliers, made up from railway workers throughout the region. Again Soldiers Died records reveal many men who were born and resided elsewhere came specifically to Hull to enlist.

Within the first six month of the war, over 20,000 men from Hull had enlisted, and by the end of the war some 70,000 had served in all branches of His Majesty’s Services. The recruits served for a variety of reasons – some out of a sense of duty and patriotism, some for a change and adventure, others for money. However, all answered the call to do a practical job, with little idea of what lay before them. Over 6,500 of these men who enlisted in Hull died in the war, Soldiers Died records reveal that the number of deaths increased during the war, with 197 deaths in 1914, 816 deaths, in 1915, 1,798 deaths in 1916, 1,781 deaths in 1917 and 1,978 deaths recorded in 1918.

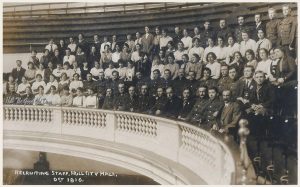

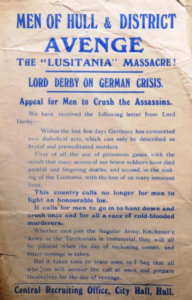

Hull City Hall Recruitment Office

Hull City Hall, was the Main Recruitment Office. It was owned by Hull City Council who paid for its rent, heating and lighting and opened on 1st September 1914. Its larger, more central location provided all the administration associated with recruitment. Led by Mr Douglas Boyd, a Ratings Supervisor, at the Hull Corporation, the City Hall, bedecked with flags and posters, became one of the most efficient recruitment centres in the country. Between 400-500 volunteer Clerks worked in Hull and recruited continuously throughout the war. This included one hundred School Mistresses and lady teachers, who on the 15th August 1915 dealt with over 12,000 recruits.

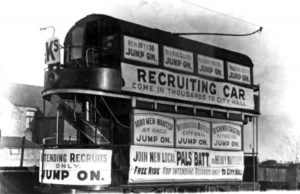

The Tramways Committee based at the Hall, provided free cars for recruitment and war advertising. For example, the Hull Corporation tram, on route H, along Holderness Road, was bedecked with recruiting adverts. Volunteers were asked to jump on, for a free ride to enlist at Hull City Hall.

Recruitment began at 10 am on the 1st September, 1914. While most of the early recruits were from Hull, it recruited men from all around the country. The Hull Pals attracted recruits throughout the East Riding, and even men from Lincolnshire and Goole. Being a port, Hull was a stopping place for men from all round the globe and many ship crews and dock labourers, enlisted in the Hull Battalions. Similarly, the 17th Northumberland Fusiliers a Railway Pals battalion, formed in Hull, attracted North Eastern railway workers throughout the region.

As well as recruitment Hull became the administrative center for appeals against recruitment. The Hull Corporation also established the Hull Military Special Tribunal, to hear applications for exemption from war service (under the 1916 Group System and Military Service Act.) Although mostly known for their decisions regarding conscientious objectors, the majority of the tribunal’s work dealt with domestic and business matters. Their work including individual cases, can be found at The Hull History Centre, ref C WE/1-3

The Creation of the Hull Pal Battalions

General, Henry Rawlinson initially suggested that men would be more willing to join up if they could serve with people they already knew. Lord Derby was the first to test the idea when he announced in late August that he would try to raise a battalion in Liverpool, comprised solely of local men. Within days, Liverpool had enlisted enough men to form four battalions, each a 1,000 strong.

‘Pals Battalions’ proved popular elsewhere. Stockbrokers, Miners, Railway workers, sportsmen and artists, all formed their own battalions. In the first two years of the war, over 3 million men in the UK joined and from the 1,000 new battalions created, over two thirds of the men were locally raised Pal battalions. The 1916 Military Service Act would conscript a further 3.5 million over the next two years.

More than 50 Cities and towns raised their own ‘Pal Battalions’. Hull with a relatively small population, raised five Hull Pal battalions, known as the “Hull Commercials”, “Hull Tradesmen”, “Hull Sportsmen”, “T’Others” and the “Hull Bantams”. They became the newly formed, 10th, 11th, 12th ,13th and 14th East Yorkshire Battalions. This was the same number of Pal battalions as Liverpool, and more than Birmingham and Glasgow which had three. Manchester had seven. Newcastle had two, but had an additional four called the Tyneside Scottish Brigade and another four called the Tyneside Irish Brigade. The bonds of friendship were a major strength in building an effective fighting unit. However, the tragic consequences of this were that heavy casualties could decimate all of the men from the same street, team, or workplace.

The 10th ‘Hull Commercials’ Battalion were initially recruited at the Army Office, located at 22 Pryme Street, Hull. However, this became inadequate to cope with the large numbers of volunteers enlisting. Recruitment was therefore moved to Hull City Hall on the 6th September 1914.

The 1st Hull Battalion, known as the Hull Commercials (10th East Yorkshires) were recruited in 5 days. They were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel, RB Carver, a retired Militia Officer and later Lieutenant Colonel, AJ Richardson, who had commanded the 1st East Yorkshire Regiment in 1911.

The 2nd Hull Battalion or Hull Tradesmen (11th East Yorkshires) were raised within 3 days. They were under the temporary command of Lieutenant Colonel, LJ Stanley, with the Headquarters based at the Hull Cricket Pavilion on Anlaby Road (now the KCom sports stadium).

Recruitment for the 3rd Hull Sportsmen Battalion (12th East Yorkshire Regiment) began on 12th September 1914. By October it had raised 25 Officers, 1,228 other ranks, and a Depot Company. It was based at Park Street Barracks and drilled in Pearson Park.

Recruitment for the 4th Hull Pals (the 13th East Yorkshire Regiment) began on 16th November 1914. This received all able bodied volunteers, regardless of class and trade and became known as the “T’Others”. Commanded by Lieutenant Colonel, RH Dewing, a retired Indian Army Officer, they had no permanent barracks, but trained at the Market Place in Hull City centre.

Hull later raised a 5th ‘Bantam’ Battalion (the 14th East Yorkshire Reserves) in 1915. This was recruited from the Depot Companies of the 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th East Yorkshire Regiments and was made up of ‘small men, with big hearts’, who were 5 foot 2 tall, or under. It became known as Lord Robert’s, or ‘Bobs Battalion’.

These five Hull Pals Battalions were more than many other Cities, which had larger population and reflected Hull’s patriotism. The Hull Pals, were unusual in that it formed its own Hull Brigade. The 10th, 11th, 12th ,13th and 14th East Yorkshire Battalions became the 92nd Infantry Brigade, in the 31st Army Division. At the same time, Hull men also enlisted in the regular army and other Yorkshire regiments. Hull also recruited three Heavy Artillery Batteries and a Divisional Ammunition Column, for the 31st Hull Brigade. Hull also equipped two Volunteer battalions made up of local Golfers, for Coastal Defence, raised its own Army Service Corp in 1915 (the only City to do so) and created Britain’s first Anti-Aircraft Unit, which was raised in Hull, within 14 days. It recruited the 17th Northumberland Fusiliers (the Railway Pals) at Hull’s Albert Dock, as well as sailors and crew, for Britain’s Royal Navy. Merchant Navy, Royal Naval Reserve and Auxiliary fleets. This was an extraordinary effort considering that Hull still needed manpower to work its many docks, service munition factories and other “Reserved” occupations.

By the end of December 1914, Hull proudly boasted four Pal Battalions, and a Reserve Regiment, each at full active strength, and with Depot companies which could be used as replacements. Due to the way they were recruited, there was much competition and snobbery between the Hull Battalions. The Commercials made up of middle class, office clerks and teachers saw themselves a cut above the rest and many were commissioned into other regiments as the war progressed. The 11th Hull Tradesmen, were factory and shipyard workers, boiler makers, plumbers, and builder labourers. They brought many practical skills and cheerfulness to the battalion. The 12th Hull Sportsmen, recruited from Dockers, were a hardy lot, and included the “Silver Hatchet Gang”, which in peace time, had a violent reputation in the Hull docklands. The 13th East Yorkshires or “Hull T’Others”, were largely men too late to join the first three Pal battalions and composed a wide range of backgrounds. Competition was particularly fierce to join the 5th Hull cyclists, who with their ‘knee britches and black bugle buttons’ were seen as a rather noticeable unit to belong to.

Hull Pals Training and Service

Initially the Hull Pals, lived at home. There was simply not enough room to accommodate them all. They trained in civilian clothes with only battalion arm bands to distinguish them. They used broomsticks for weapons. Their instructors were Senior NCO’s, retired soldiers brought into service and Temporary officers. Few had recent war experience. All ranks were temporary and it was not until January 1915, that specialists were selected and Company Commanders recommended men for Commissions. The hardships of army life were a tough transition. Many civilian recruits were not used to the physical exertions of rout marches. Sports and competition within and between battalions helped weld the men together and improve their physical fitness. For example, on 21st April 1915, a Hull Brigade Cross Country run was organised between Dalton and Victoria Barracks in Beverley, which was the East Yorkshire Regimental Depot.

The Hull Pals were initially trained in Hull and Beverley from 6th October 1914 to 16th February, 1915. They drilled on Walton Street Fair Ground, the Anlaby Road “Cricket Circle”, Hull Market Place and in Pearson Park. Here they practiced extended order drill, outpost duty, judging distancing and skirmishing.

The Hull Pals finally received complete kharki uniforms in November 1914. They now began to develop separate field exercises and manoeuvres. The 10th East Yorkshire moved to Hornsea for coastal defence duties in November 1914. They guarded the area between Mappleton and Ulrome and built a camp next to Howden rifle range. They got to fire Lee Enfield Rifles for the first time on Christmas Day. The 11th East Yorkshires moved

to Pocklington. The12th East Yorkshires moved onto the Dalton Holme Camp, Beverley, from 16th February 1915 to 16th June 1916. This was a large estate owned by Lord Hotham, situated 5 miles, North West of Beverley. Training became more intense with Trench digging, bayonet drill, semaphore signalling, musketry and knotting.

The Hull Pals then moved to Ripon Army camp, North Yorkshire, between 18th June 1915 to 28th October 1915.

They transferred to Salisbury Plains, Wiltshire, from 29th October 1915 to 12th December 1915 where they were instructed in Trench warfare. They settled in new quarters at Hurdcott Camp and the 10th Battalion at Larkhill. During this time those medically unfit were released for munitions work at home. On 3rd December 1915, men were issued with identity disks and pith helmets, the first hint that they were being posted abroad..

Egypt and Defending the Suez canal

The Hull Pals were ordered to Egypt, on the 11th December 1914. They travelled by train to Devonport, Plymouth, and embarked on HMT Ausonia, sailing at 12.30pm on December 16th 1915. They called at Valetta, Malta and Alexandria and arrived in stages, at Port Said, between the 24th and 29th December 1915. Their objective was to defend the Suez Canal from a perceived Turkish attack after the Gallipolli Campaign.

arrived in stages, at Port Said, between the 24th and 29th December 1915. Their objective was to defend the Suez Canal from a perceived Turkish attack after the Gallipolli Campaign.

After three months in Egypt, the Hull Battalions transferred to France. They left Port Said, Egypt, on 29th February 1916 and embarked for France on the HT Simla. They sailed at 6.00am on the 1st March 1916, arriving in Marseilles at 11.50pm on March 8th after an ‘uneventful voyage’. Disembarking the following day they left Marseilles by train, on March 10th, bound for Pont Remy, which is 7 miles south east of Abbeville in the Somme region of Northern France. They arrived early in the morning of March 12th. The battalion then undertook a series of route marches to arrive at Colincamps, on the Somme, arriving on 6th April 1916. The battalions then settled into a routine of a few days in the trenches, including repairing them, followed by a few days in billets where they trained in ‘bombing, signalling, (barbed) wiring and “Lewis gun work’.

The Somme & Serre

Between April and June 1916, the battalion moved between Colincamps, Courcelles-Aux-Bois and Bus-Les-Artois. The division was introduced to trench warfare in front of Beaumont-Hamel and Y Ravine. Over the following weeks the battalions took their turns in the routine of trench holding, working parties, patrolling and trench raiding, with a constant drain on manpower from shelling and snipers. Shortly afterwards the 31st Division formed its own light trench mortar batteries (TMBs). It also provided working parties to assist the 252nd Tunnelling Company, Royal Engineers, digging the Hawthorn Ridge mine that was to be exploded to launch the forthcoming Battle of the Somme.

The Hull Pals were lined up in support, for the initial attack at Serre, on the 1st July 1916. Their assault was fortunately postponed due to other heavy losses earlier in the day and they escaped with relatively few losses. On 2 July the shattered division was pulled out of the line and sent north to a quiet sector for rest and refit, though there was the usual trickle of casualties associated with trench holding and raiding.

The 31st Division returned to the sector for the Battle of the Ancre, which was to be the last big operation of the year. Serre had still not been taken, and the 92nd Brigade was assigned to the attack alongside 3rd Division (the rest of 31st Division was still too shattered to take part). A 48-hour preliminary bombardment began on 11 November, and the brigade moved into the trenches on the night of 12/13, along communication trenches clogged with mud. Zero hour was 05.30 on 13 November, and fog, light rain and a smokescreen reduced visibility to a few yards, so that the leading battalions initially had little difficulty, but the 3rd Division on their right made no progress. Small-scale fighting went on all day, and Private John Cunningham of the 12th East Yorks won Hull’s first Victoria Cross (VC) for fighting on alone when all the rest of his team of bombers became casualties. At the end of the day the brigade had been driven back to its starting positions and suffered over 800 casualties.

The Division remained on the Ancre throughout the winter of 1916-1917, following up the Germans, when they retired to the Hindenburg Line, in the Spring of 1917.

Arras & Oppy Wood

After resting and regrouping, the Hull Pals left the Somme and moved to the Arras sector, on the 8th April 1917.

On the 3rd May 1917, the Hull Brigade attacked again in force, at the Village of Oppy Wood. It was a largely a diversionary action, but the Germans were heavily defended in the woods and inflicted severe losses on the Hull Pals. Lieutenant, Jack Harrison was awarded Hull’s second Victoria Cross posthumously at Oppy Wood. Casualties in the 12th East Yorkshire had been so severe, that it was temporarily reduced to two composite companies, attached to the 10th and 11th Battalions respectively.

A fresh attack on Oppy Wood was arranged for 28th June. This time the attack was to be made by the 94th Brigade with the 92nd Brigade in support. The attack was made in the evening of 28th June and successfully took the trenches, completing the Capture of Oppy Wood.

After the decimation at Oppy Wood, the Hull Pals were merged and amalgamated with recruits from other regiments. The original spirit of the Hull Pals was largely diluted, but they continued in action. One notable achievement was delaying the German Spring Offensive in March 1918, when the Hull regiments, played an important role in defending Ervillers and the Ayette aerodrome, against repeated attacks. Only events elsewhere forced the East Yorkshires to withdraw and they were eventually relieved on the 31st March.

La Becque and Ploegsteert

Once out of the line the division began training for offensive operations. 31st Division took part in Operation Borderland, a limited attack on La Becque and other fortified farms in front of the Forest of Nieppe on 28 June, in what was described as ‘a model operation’ for artillery cooperation. Individual units continued to make small advances through aggressive patrolling and seizing strongpoints (so-called ‘peaceful penetration’) until the Allies began a coordinated offensive in August. The division captured Vieux -Berquin, on 13 August 1918 and pushed forward until running into serious opposition south of Ploegsteert, on 21 August, where fighting continued into September, 1918.

A formal attack was arranged for the morning of 28 September (the opening day of the Fifth Battle of Ypres). Although suffering heavy casualties, the 92nd Brigade and a battalion from the 93rd Brigade took their objectives, though they were shelled out part of Ploegsteert Wood. The rest of the 93rd Brigade then crossed the Douve stream accompanied by artillery and engineers, the 94th (Yeomanry) Brigade was held up the rear). The general retirement of the Germans along the whole line then allowed the division to push on through Ploegsteert Wood and advance up to the River Lys, on 3 October.

The Final Pursuit

Returning to the line on 12 October, patrols from the 92nd Brigade slipped across the Lys on a raft during the night of 14/15 October and established posts on the far bank. The following afternoon further parties crossed and advanced under a barrage to the Deûlémont–Warneton road. The brigade continued the advance on 16 and 17 October, liberating several villages. By 18 October the battalions were advancing in company columns screened by XV Corps cyclist battalion, leap-frogging forward to liberate Tourcoing. Pressure was kept up through the 19th and 20th October, until the brigade was squeezed out of the advancing line between Second Army and Fifth Army and went into support, while the 93rd Brigade held the junction between the two armies and continued up to the Scheldt.

The division was back in the line from 28th October, with the 92nd Brigade in the lead continuing to advance slowly against machine gun and shell fire, from rearguards who ‘did not appear disposed to give ground’. The division then made an attack at Tieghem on 31 October 1918 that was so successful that the 92 Brigade in reserve was not required while the 94th (Yeomanry) Brigade drove the enemy behind the Scheldt.

The 31st Division returned to the line on the night of 6/7th November, crossing the Scheldt and sending forward the 11th East Yorkshires as part of a pursuit force, including a field artillery battery and companies from the divisional machine gun battalion, the Motor Machine Gun Corps and XIX Corps cyclists. When the Armistice with Germany came into force on 11 November, the 11th East Lancs were leading the division, and scouts reported that there were no enemy in front

.After the Armistice with Germany, on 11 November 1918, Hull’s artillery and New Army units were progressively demobilised and sent home. On 29 January the two East Yorks Battalions were sent by rail to Calais, to deal with possible riots by men working in the Ordnance depot. Demobilisation accelerated in February and by April 1919 the battalions had been reduced to cadres, which left for England on 22 May. During the war the division’s casualties amounted to 30,091 killed, wounded, and missing.

Home coming

From 17 November to the end of January 1919, Lady Nunburnholme (Lady Marjorie Wynn-Carrington) and her Peel House VAD workers welcomed home the shiploads of returning British Prisoners of war at Riverside Quay, Hull. Lord Nunburnholme, (Charles Wilson, 2nd Baron Nunburnholme), was back in Hull in time to officiate for the Lord Mayor, on 30 April 1919, to welcome home the cadre of the 7th (Service) Bn, East Yorkshires, before they marched to Beverley to disband. The cadres of the remaining battalions of the Hull Pals arrived at Hull Paragon Station, on 26 May 1919 and after being inspected by Nunburnholme they marched through the city to the Guildhall and officially disbanded.

The following is a transcript of the notes from the pocket book/diary of Henry Herbert Broughton – a soldier who served in the East Yorkshire Regiment, posted to Egypt to defend the Suez Canal and then to Northern France, to fight on the Western Front.

Left Ballybunion 28th Feb and arrived Ballah same day.