Background

When war began in 1914, there was already much anti German feeling in Britain. This Anglo German enmity, probably started 50 years before, when Britain supported Denmark, against the German reunification of Schleswig–Holstein in 1863. Britain had also sold weapons to France against Germany, during the Franco Prussian war in 1870. There was an ‘arms race’ for naval superiority between Britain and Germany from 1898 onwards, with the 1908 German Naval Bill directly challenging Britain’s naval supremacy. Germany had bitterly opposed Britain during the Boer Wars. The signing of the Entente Cordiale (friendly understanding) in 1904, between Britain and France, officially cooled relationships with Germany. A series of colonial disputes between these rivals also added to international tensions, most notably with the ‘Tangiers Incident’ in 1905 and the ‘Agadir Crises’ of 1911. Anti Germany feeling also grew against the increasing numbers of Germans living in Britain. Between 1851-1891, some four million Germans migrated away from Germany. While many of them headed for America, many Germans settled in England, becoming one of the largest, single migrant groups in England, second only to Russian Jews. The1911 Census, shows 53,324 German people living in England, mostly in London. Newspapers, propaganda and cartoons of the time, in both Britain and Germany, fostered prejudice, alarm and mutual resentment between Germany and Britain. This was not unique to Britain. Russia, America and many Europeans also resented and felt threatened by German influence, before war began.

When Germany invaded neutral Belgium and northern France in 1914, thousands of Belgian and French civilians became refugees. There were widespread reports of German atrocities and executions of civilians by German soldiers. These acts were used to encourage anti-German sentiments and the allies produced propaganda depicting Germans as Huns capable of infinite cruelty and violence. On 5 August 1914, the Aliens Restriction Act was quickly passed by parliament the day after war was declared on Germany requiring foreign nationals (aliens) to register with the police, and where necessary they could be interned or deported. This act was chiefly aimed at German nationals and later other enemy aliens living in the United Kingdom. About 33,000 “foreign nationals” and 20,000 Germans were interned, men in specially created camps and a small number of women in prisons and asylums. Many innocent people suffered hardship and injustice. Some 6,000 men with sons serving in the British armed forces were still interned during the war.

With mounting war casualties, an atmosphere of hate towards anything German grew during the war. Anti-German riots occurred intermittently in British towns and cities throughout the war. In 1915, riots in Southend, Liverpool, Manchester and East London were widely reported where mobs of people plundered property and attacked anyone suspected of being sympathetic towards the Germans. Anti German feeling strengthened in 1915, with the first use of poison gas by the Germans, on the battlefield. The sinking of the ocean liner, “Lusitania”, on 7th May 1915, was another catalyst. This passenger ship was sunk by the German UB20, with some 1,200 civilians, including 94 children killed. The German Shepherd breed of dog was renamed the “Alsatian”. The German biscuit was renamed the “Empire Biscuit”. Street names after notable Germans or places in Germany were also changed. Midway through the war on 19 June 1917, King George V and the British royal family discontinued the use of the

ir German titles and surnames, changing their family surname from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor. In 1918, there was a further wave of anti-German feeling in the spring and summer with initial German successes on the Western Front and war weariness.

Hull was no exception and in many ways was a divided city with much prejudice. At the start of the war, all German residents had to register with the authorities. The Hull Times reported that by the 7th August 1914, 170 people in Hull had done so, and of these, a half had been detained. However, there were many people who were either of German descent or naturalised British subjects and they became the target of mob hatred. In Hull, many of the pork butcher shops were owned by such people, and with names being prominent, they became an obvious target. The first such incident occurred on Saturday, 24th October 1914, outside the pork butcher’s shop owned by Mr C.H. Hohenrein. A large crowd gathered outside the shop and two men were arrested for being drunk and disorderly, they were arguing as to whether the shop should stay open. However, Mr Hohenrein, although of German descent, was a British citizen, patriotic and supportive of the war effort.

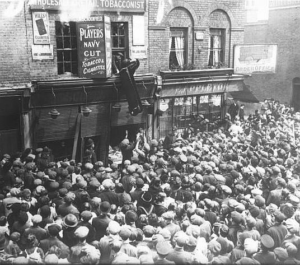

A more serious riot happened on Saturday, 15th May 1915, when a large crowd of 500 people moved down Hessle Road, attacking shops suspected of being owned by Germans. The Hull Daily Mail reported that the shops of a Mr Schumm and Mr Steeg, both pork butchers on Hessle Road, both had windows smashed. Also in Charles Street, Mr Lang’s shop was attacked. In all these cases the owners were naturalised British subjects, (in Mr Schumm’s case, for forty years), and fully supportive of the war.

In response to trawler losses, (Eight Hull Trawlers were sunk on one day – the 3rd May 1915), and the first Zeppelin raid on Hull, on 6th June 1915, which murdered women and children and made many homeless, anti German demonstrations again broke out throughout Hull. Women were amongst the most rowdy demonstrators, as feelings on their men away at war spilled over. These demonstrations lasted 3 days in Hull. There were 50 reported incidents of violence and many arrests for public disorder. Anything German became a target. Four German owned shops on Hessle Road and a pork butcher on Charles Street were attacked by angry crowds of up to 700 people. A mother and daughter were charged with stealing furniture from German shops, a man stole a mattress, others stole food. A German Grand Piano was destroyed. Another pork butcher’s shop called, Hohenrein, at 22 Princes Avenue, was attacked and threatened several times. The damage and theft in Hull was substantial. The Watch Committee Minutes for 27th August 1915 lists 49 claims for damages by Hull people you suffered during the 15th May riot, and many of the names are distinctly German. In all some £258,000, was eventually paid out in Hull for compensation. The German Zeppelin raid on Hull 6th June 1915, effectively decimated the long standing, German community, in Hull. German churches, culture and businesses declined in Hull thereafter. Many Germans left Hull and those who remained changed their names, including the Hohenrein family, who changed their name to Ross to deter protesters. In the case of Mr William Schumm, he changed his name to Shaw to avoid further trouble. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01qvvf8

Other naturalised citizens, like the Gohl family, who were not German, but from Austrian and Danish descent, suffered the same discrimination. They altered  the pronunciation of their name (from Gohl to Goll) to avoid recriminations in the war, and issued public notices to show that the Gohl family was serving Britain during the war.

the pronunciation of their name (from Gohl to Goll) to avoid recriminations in the war, and issued public notices to show that the Gohl family was serving Britain during the war.

Julius Gohl had arrived in Hull, from Hamburg in the 1867, at the age of two. He married an English woman, Susannah Carter in 1887. Together they established a very successful wholesale and retail confectionery business, with shops in prime locations, and a factory/warehouse in Hull. The outbreak of war in 1914 was a great tragedy for the whole family, as having the surname GOHL meant that Julius and Susannah were classified as “enemy aliens”. This was despite five of their children, all British born, serving with the armed forces. When Britain declared war on Germany, Britain hurriedly introduced the “Alien Restriction Act “ where all ‘aliens’ where required to report and register with the police. Julius placed an advert in the Hull Daily Mail showing the family’s dedication to King and Country. Their son, Edward Gohl was killed in the war and Harry Gohl was wounded. The Gohl’s sweet shop at 73 Queens Street was also damaged in a Zeppelin raid, which no doubt helped dispelled any local hostility towards the Gohl family.

Many culprits of the ‘anti German’ violence were unpunished or shown leniency. One particularly perpetrator escaped a prison sentence by enlisting in the army. Hatred of everything German increased and showed itself in the most detestable ways. A Hull born man, who probably did not know that his father was German, until showed a birth certificate, was dismissed from his post in the Work House. His ‘Guardian’ found it necessary to confess that he’d known him for 20 years as a docker, but never suspected this ‘Teutonic Taint’.

Alfred Donnison, was another Hull man, accused of being a German Spy. Alfred was born in Hull, a Boiler Maker, aged 60, who had served in the East Riding Territorials for 28 years and enlisted when war began. He was overheard by a woman, to say “God Bless the Kaiser”, in Chariot Street, Hull, in May 1915. Stopped by two off duty soldiers,(Gunners, Wilfred Price and Parker), Alfred was roughly handled, arrested and taken to Hull Central Police Station. He fell ill during Police questioning, and put in a cab, but never made it home. The story was reported in newspapers, as far apart as Coventry and Dundee. The two soldiers involved were reprimanded by the Coroner, but no further action was taken. The Home Secretary was asked in Parliament whether there should be legislation to prevent recurrence, but he considered it too rare to justify such action.

Another victim of these reprisals, was Max Schultz’s family, who lived at 82 Coltman Street, Hull. Max Schultz was actually a British Spy before the First World War. He was born in Hull to Pomeranian, emigrant parents, on their way to the United States. For unknown reasons, they broke their voyage, stayed in Hull and opened a shoe shop. Max Schultz became a ship owner by trade, and little is known of how he came to work for the British Secret Service. The Admiralty was suspicious that the Germans were secretly accelerating their shipbuilding program, namely stockpiling guns, turrets, and armour, well in advance of actually building the battleships. (Building the guns, gun mountings, and armour was more time-consuming than building the ships themselves, and stockpiling could cut the three years required to build a ship, to two and a half or two years.) It was suspected that construction was being started in advance of the dates scheduled by the German Navy Law, in advance even of the authorisation of funds by the Reichstag. The consequence of such subterfuge could be dramatic: instead of a 16:13 battleship ratio in favour of Britain in 1912, Britain was facing the possibility of a ratio anywhere from 17:16 to 21:16 in favour of Germany. It was in this atmosphere that Britain formed the Secret Service Bureau, on 1st October 1909 and Schultz was recruited. During his travels in Germany in 1910-11, Schultz recruited four informants, the most important being an engineer named Hipsich, in Bremen’s Weser shipyards. In the two years Hipsich operated, before being detected, he had the opportunity to inform the British about Germany’s battleship plans and apparently handed over a large collection of drawings.

Max Schultz was arrested for running a spy ring in Germany in 1911, where he served seven years of hard labour. (At the same time, a genuine German spy with the same name, Max Schulz, was arrested in Portsmouth for trying to procure naval information for Germany.) Unfortunately, Hull residents did not realize what Max was doing for Britain before the war and his wife Sarah Hilton & their five children suffered abuse and their house was stoned (as were many families with German sounding names). Sarah changed the family name to her maiden name Hilton. During his time in prison, Max Schultz built a model of the ship ‘Imperator’, which can be seen in Hull’s Maritime museum today. He hid a letter relating to his prison experience in one of it’s funnels. After returning from Hamburg, were he remained after the war to instigate unrest in the German navy, Max had a yacht, the ‘Lady Esmeralda’, moored on the Thames, and a mistress. He died of alcoholism in 1924, aged 49.

* Thank You to Roger Kemple for supplying information on Max Schultz, Brian Gohl for information on the Gohl family, Maggie and Richard Taylor for the story of Alfred Donnison.