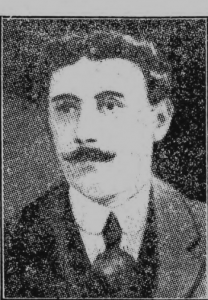

Pte, Charles Frederick McColl, 11/81, 1/4th East Yorkshire Regiment, (pictured) was executed for desertion in 1917, aged 26. He was the son of Annie McCol of 6 Bramhan Avenue, Woodhouse Street, Hull. Little is known about his early life. McColl had three sisters and a brother, who at some time lived at 209 Hedon Road, Hull. The 1911 Census, records him as a nineteen year old, ship plater for Earle’s Shipyard, and boarding at 100 Egton Street, Hull. At the outbreak of war, McColl gave up his reserved occupation, to enlist in the 11th EYR, on the 7th September 1914. This was the 2nd Hull Pals or ‘Tradesman’ Battalion. Initially McColl was like the rest, but between the 25th March 1915 to 24 February 1917, he committed a number of offences during training, prior to his execution.

The Public Records Office show these offences, as being absent without leave, being late for parade, stealing four eggs, being drunk and disorderly, and travelling by rail from Newcastle to Hull, without a valid train ticket.

As a consequence of these misdemeanours, McColl did not leave with the battalion to Egypt, but remained stationed at home. Records after this are scarce, but it is believed McColl went to France in April 1916. He was buried by a shell, at Neuve Chapelle, in September 1916 and invalided home suffering from ‘heart failure and nervousness’. He was returned to France without a medical examination and posted not with the 2nd Hull Pals, which he had trained with, but the 1/4th EYR, a Territorial battalion. He ‘absented himself without permission‘ on the 22nd July 1917 and was caught later at Etaples, on the 25th August 1917. He was tried on the 13th September 1917 and given 10 years imprisonment, suspended on condition that he returned to front line duties. He absconded again a week later, on the 22nd September 1917 and was arrested 3 miles behind the line, the same day. On the 11th October 1917, he received 90 days Field Punishment No:1, for being ‘Absent without Permission‘. Before his punishment was carried out, he deserted again on the 28th October 1917, this time leaving his rifle and equipment behind in the support trenches, at the Houlthult Forest, during the Third Battle of Ypres. This was his final transgression. He was arrested by the Military Police at Calais, on the 1st November 1917. He is believed to have lived with a woman at Calais and was trying to make his way back to England by entering a Rest Camp. On his arrest for desertion, Private McColl entered a plea of ‘Not Guilty’.

The Court Martial was presided over by Major Graham, of the 5th Yorkshire Regiment. The other three members of the court were Captain Pollock, of the 4th East Yorkshire Regiment, Lt., Morrison, of the 5th Durham Light Infantry, and Captain Baker. The witnesses called, were Platoon Sergeant, Len Cavinder, of the of 4th East Yorkshire Regiment, who had reported McColl missing in the trenches and L/Cpl Dearing, of the Military Foot Police, who arrested McColl asking directions to the Rest Camp. At his trial, no medical evidence was available and McColl called no witnesses. On Oath, Private McColl stated:

“I was brought out of the guard room before going up to the line and was in a weak position. This was about 26th October 1917. We marched up to Marsoin Farm, I had complaints brought on by shell fire. I have heart failure and nervousness. I have been with this battalion 6 months, but only reported sick once. I always shake from head to foot when we go into the trenches.

I enlisted in September 1914 and went to Egypt in November 1915 and came to France in April 1916. I was buried by a shell at Colincamps in September 1916 with the12th East Yorks. I was on two or three raids and then my nerves went. I was invalided home in September 1916 suffering from heart failure and nervousness and was classified A3 at the finish and sent back to France without any medical examination. Since joining this battalion, I have tried to do my best. When I went off, they dropped shells all around me and this upset me more and more and I wandered away. At Calais I was in a weak condition and handed myself in to the Military Police. I am not fit now. I had a knock on the head from a shell in BUS wood.”

Private McColl was then cross examined by the prosecutor and stated: “I have been in front line trenches with this battalion on about 6 different occasions. I have been here since July. The trenches I was in were at places I can’t remember. One place was Bullfinch Trench, I was there 8 days. Another was Jackdaw Trench.”

The Court called for medical evidence, but none was available. In his final statement, McColl pleaded for leniency:

“I came from an exempted trade – shipyard plater – to join the army voluntarily in 1914. I am the only support of my mother who is a widow. I have tried to do my best.”

Private McColl was found ‘Guilty of Desertion’. The Sentence of Death was soon confirmed by Field Marshall Douglas Haig.

Charles McColl had not been told of his fate when he was taken to Ypres gaol. Sergeant, Cavinder and Private, Danby had the job of keeping him quiet, to which end, they had been given half a bottle of scotch and some sleeping tablets.

Cavinder later recalled events on the night before the execution, “At midnight, in came a string of brigade officers and the captain in charge of the firing party, and I was told to stand him to attention. They read out the sentence of death, signed by King George V. I’ll never forget that. The prisoner nearly went raving mad.”

The Sergeant – himself a teetotaller – tried to give Pte, McColl, whisky, mixed with Laudanum tablets containing morphine to calm his nerves. But McColl, minutes away from his own death, was too shaken to take it. “He started to cry and I got the bottle of whisky out,” Sgt, Cavinder said. “He wouldn’t drink the blinking stuff. If I could have got him drunk, I would have done.” The pair’s meeting was then interrupted by a priest, who was horrified to see drink being offered as a comfort to the prisoner. The Padre threatened to report Sgt, Cavinder to the authorities. “You can do what you like,” the Sergeant replied. When McColl calmed down, the Padre talked to McColl, but instead of supporting him, told him that he deserved to die. At this point Cavinder thought it necessary to take over and try to calm McColl down again. At 7am, two Military Policemen entered the cell and placed a gas mask, backwards over McColl’s head, so he could not see what was happening. They then pinned a piece of paper over McColl’s heart. Cavinder shook hands with McColl, before they manacled his hands behind him. McColl was taken to the execution area and sat on a chair, with his hands behind the back of the chair. McColl was executed by ten men from his own company, five kneeling and five standing. Only five of the ten rifles were loaded with live ammunition. The ten man firing squad consisted of seven members of the ‘Black Hand Gang’. These were former Hull Dockers and the toughest men in the Battalion. They were use to doing the dirtiest of jobs and invariably did the trench raiding. The firing party took aim, and on the command of ‘Fire!’, executed Private McColl, at 7.41am, on the 28th December 1917. McColl died instantly. The men who shot McColl were dismissed and later given a extra dose of rum. After the firing party had left, the RAMC were supposed to bury Private McColl, but after they had unmanacled him and put him on a stretcher, they too left. It was therefore up to Cavinder and Danby to drop McColl’s body into a previously dug grave. No Padre was present, so Cavinder muttered some words and they covered the body with frozen clods of clay as best they could. McColl’s Company Commander, Captain, Cecil Moorehouse Slack, wrote home to McColl’s mother, to tell her that her son had been ‘killed in action’. It is likely that the War Office contacted her with the real reasons.

Sergeant, Len Cavinder recorded his war memoirs in 1982. He recalled that Private, McColl was “one of those cases that in the next war would have been dealt with better because he wasn’t 100 per cent,” Sgt, Cavinder stated that McCol was of of low intelligence and “pretty hopeless in the line.” “He was subnormal actually…… He was unstable. There was something wrong about him… I realised you couldn’t get him to slope arms correctly, and all that sort of thing. He wasn’t simple, but he was slow .” He suggested that Private McColl should never have been made to enlist, as his low intelligence made him unable to make proper decisions. Britain was desperate for soldiers and recruited many who were elderly and unfit for duty. McColl was one of these men and he had been unwisely thrust into a war that he just could not understand. Captain, Cecil Slack, who supervised the execution was less sympathetic. Tracked down and interviewed in the 1970’s, Slack remained unrepentant about the execution stating McColl “was intelligent enough to find a woman and live with her for three months after he deserted.”

It seems that the War Office contacted Annie McColl, his mother, and made it brutally clear that that her son was an undesirable, executed for cowardice and desertion. No war pension was awarded. His Army Medals were forfeited. His name does not appear on any memorial in Hull. Apparently he was even refused a Christian Burial by the Padre at the time, which was unprecedented, even for soldiers facing execution. For decades the family felt too ashamed to discuss the matter. Even when local newspapers revived the McColl story, a surviving relative of Charles McColl wished to remain anonymous.

In November 2012, Jim Dunne retold the McColl story in a play, called “Shot at Dawn”, produced at the Hull Truck Theatre. The McColl execution was recounted using written transcripts from the actual trial and saw McColl trapped in limbo, asking for a fair hearing beyond the grave. The audience was left to draw their own conclusions. Charles Fredrick McColl is buried at the Ypres Reservoir Memorial, Grave Reference 1V: A6. The 1914-18 War Medal Roll, records McColl as ‘dead; medals forfeit for desertion’. Although Charles Frederick McColl lived in the Sculcoates Parish of Hull, his name is not recorded on any Hull war memorial. In 2014, the Lord Mayor of Hull visited the grave of Charles McColl, at Ypres. Accompanied with a Chaplain she ensure he had a Christian burial.

Private, Charles McColl was one of 306 British and Commonwealth troops executed during the First World War. Of these 25 were Canadians, 26 Irishmen, 15 Welshmen and five New Zealanders. Four of the 306 were 17 years old. Three were Officers.

During the period between August 1914 and March 1920, there were 200,000 Court Martials. More than 20,000 servicemen were convicted of offences which carried the death sentence. Only 3,076 of these men were ordered to be put to death and of those, just 11% were executed. Execution depended very much on the time, place and circumstances of the soldier involved. The first ww1 execution, was Private Thomas James Highgate, of the 1st Battalion of the Royal West Kent Regiment, who was shot at dawn on the 8th September 1914. A 17-year-old, former farmhand and only son, Thomas Highgate was executed for desertion at the battle of Mons, just 35 days into the war. Highgate did not speak and was not represented during his trial. He was told, at 6.22am, that he was to be put to death: “At once, as publicly as possible.” A firing squad was prepared and, by 7.07am, Highgate was dead. He has no known grave. His mother, who lived in Sidcup, Kent, lost three sons during the war. Unaware of the circumstances of Thomas’ death, she submitted the names of all three sons to the Sidcup War Memorial Committee, and his name appears on the Sidcup Memorial.

This not to say all British soldiers executed were innocent. Cathryn Corns, co-author of Blindfold and Alone, examined all 306 courts martials. She said ‘The number of rogues outnumbered those with mitigating circumstances by about six to one.’… ‘Many were repeat deserters who showed no sign of shell shock. An individual re-assessment of these cases would undoubtedly re-convict the majority. Military justice was harsh, but life then was much harsher. Capital punishment was still used in Britain. And while the military law used was written for previous campaigns in Africa, and perhaps was not appropriate, every one of the soldiers signed up to those regulations.’

In 2007, the Armed Forces Act 2006 was passed allowing all the 306 WW1 soldiers to be pardoned posthumously, although section 359(4) of the act states that the pardon “does not affect any conviction or sentence.”

While over six million Britons enlisted during WW1 and served honourably, there were 114,502 court martial cases for desertion in the UK and 64,000 of these were prosecuted. Punishments for desertion at home were lighter, than those serving at the front. They could include a fine or imprisonment, and may be waived if the man enlisted . Soldiers overstaying leave in the UK, however, could be returned to their regiments at the front and be tried by their own Officers risking severer sentences.

Desertion in the UK remained a constant problem and grew during the war. For example, in 1915, the Manchester Police Commissioner, reported that he was receiving 200 requests a day about deserters. Some 93,000 men or 30%, failed to answer the Conscription call up in 1916. In January 1919, the UK military, estimated that desertion in the UK had drained the British army of 115,000 men during the war. This was clearly an underestimate, as many deserters were never caught.

The reasons for desertion were as varied as the men who enlisted – difficulties with money, family, conscience, criminality, protest about the war or camp conditions. Some men enlisted, then deserted and re-joined under different names. This allowed them to take several “King’s Shillings” and sell former army uniforms and equipment. Some deserters made a living by unscrupulously marrying war widows for their pension before disappearing. Some deserters remained in uniform and posed as wounded veterans, to beg money, or masqueraded as “war heroes” in uniforms to procure treats. Many deserters could find work on the land where labour was in short supply. Rural Cowling, near Skipton in West Yorkshire, became known as a “deserters village” by the authorities, for hiding men needed for farm work. Reserved Occupations were also exploited by deserters and there was a black market for forged paperwork, armbands and badges, which exempted soldiers from war service. The lack of Military Police (there were only 400 in 1914 and 4,000 by the end of the war), meant deserters could often evade capture and detection. Local policemen were given a bonus if they found deserters, and were more keen to prosecute. Some deserters changed their identity, moved town and reinvented themselves in isolated parts of Scotland, and Ireland. Others were protected and hidden by sympathetic relatives, in attics and coal cellars. Britain maintained a policy of shaming deserters. There were also some female deserters after 1917 when the women armed forces were created. Their reasons for desertion, were similar to the men, not liking the conditions or the opportunity of better paid work elsewhere. “Deserters” were not included on war memorials and pensions were not issued to families. Deserters found after the war were fined, but were less likely to be detained as their was little value in their prosecution.

Britain was not alone in executing its own soldiers. The French are thought to have killed about 918 men. The Germans, whose troops outnumbered the British by two to one, shot 48 of their own men, and the Belgians 13. The United States, shot 35, Italy 750, Bulgaria, 600. Australia refused to execute any of it’s soldiers and had the highest rate of absenteeism.

A summary of British Army executions during the First World War is tabled below.

|

Executions in the British Army: 1914-1918 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offence |

1914 |

1915 |

1916 |

1917 |

1918 |

| Desertion |

3 |

46 |

71 |

90 |

35 |

| Cowardice |

1 |

4 |

10 |

2 |

– |

| Quitting Post |

– |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| Disobedience |

– |

1 |

3 |

1 |

– |

| Murder |

– |

2 |

4 |

3 |

10 |

| Striking a superior officer |

– |

– |

3 |

1 |

– |

| Casting away arms |

– |

– |

1 |

1 |

– |

| Mutiny |

– |

– |

1 |

2 |

– |

| Sleeping on post |

– |

– |

– |

2 |

– |

| Totals |

4 |

55 |

95 |

104 |

46 |

Another executed Hull soldier was Private, George Ernest Collins, 9618, 1st Bn Lincolnshire Regiment, executed for desertion 15th February 1915, aged 20. Plot 1. B. 3. Loker Churchyard, West-Vlanderen, Belgium. He was the son of James and Charlotte Collins, of 2, West Dock Street, Hessle Road., Hull. His death was reported in the Hull Daily Mail on 15/02/1916. Another Hull soldier, was Private, Albert Parry, 2nd West Yorkshire Regiment, shot at dawn for desertion, while on active duty, on 30th August 1917, aged 43. He lived at 11, Empringham Terrace, Daltry Street, Hull, with his wife Alice Maude and their two children. He is buried at Maple Leaf Cemetery, Ypres, Belgium, Row K.4.

Not all soldiers were executed. Private, Alfred Lightowler, 5665, East Yorkshire Regiment, was discharged on 04/06/1915 for “misbehaving before the enemy in such a manner as to show cowardice.” This normally meant the Death Penalty. However, Lightowler was sentenced to 15 years penal servitude and all his medals were forfeited. Alfred was born in Hull in 1891 and joined up as a Territorial, for 6 years, in 1910. It is unclear about the details that resulted in his court martial. The Hull Daily Mail reported his death on 05/10/17. He was the son of Alfred and Martha Lightowler who lived at 109 St Marks Street, Hull. Before the war Alfred had been a Dock labourer and corn porter, like his father. He left a brother and three sisters. He has no CWGC grave.

Self inflicted wounds are also an indication of the psychological strain of warfare. While some Brigade casualty returns no longer exist, the returns for the 13th East Yorkshires during July 1916, show that on the 18th, Private, G. H. Brewitt was hospitalised for a self inflicted wound, and that on the 27th July, Private, S J Dry was reported as accidentally self-inflicting a wound. The strain of war was also showed by Officers, as seen in the 13th Battalion War Diary, which reports “July 22nd – 2/Lt. Cullen. Shell-shock; July 23rd. Captain Stevenson and 2/Lt. Swan to 95 Field Ambulance with shell-shock.”

Sometimes the enemy executed British soldiers. Private, William Lonsdale, 2nd West Riding Regiment, was sentenced to death, in Germany, for an alleged assault of a guard in a Doberitz concentration camp. This episode was reported in the Hull Daily Mail with his photograph on 4th January 1915.

Sergeant Cavinder’s account of the Execution: http://www.hulldailymail.co.uk/Brutality-compassion-World-War-trenches-tragedy/story-20454081-detail/story.html

‘In Trouble:Military Crimes‘ – http://www.1914-1918.net/crime.htm

‘World War One Executions’ – http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world_war_one_executions.htm