New Laws – Restricting Public Rights to win the war.

The Government introduced new laws to help pay for and win the war. This started with the ‘Defence of the Realm Act or (DORA) in 1914‘. Basic tax increased from 6% to 30% and the number of people in Britain who paid tax, tripled to 3.5 million. Clocks went forward to make the most of daylight hours. The Government took over coal mines, shipping, railways and land to secure supplies and food production. It set up ‘state run’, munitions factories and worked with Trade Unions to prevent strikes. All beaches along the East Coast were closed during the war.

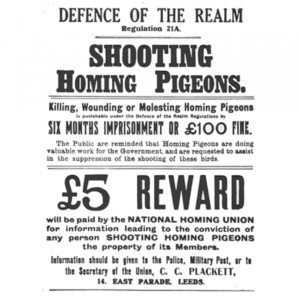

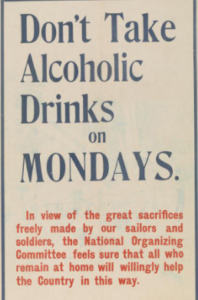

Trivial peacetime activities which were banned, included using fireworks, flying kites, starting bonfires, buying binoculars, feeding wild animals bread, discussing naval and military matters or buying alcohol on public transport. People were not allowed to whistle for a Taxis in case this sounded like an air raid alarm, or loiter around railways and tunnels. You could not spread rumours, trespass on railway lines and bridges, ring church bells, melt down gold, or silver, or use invisible ink when writing abroad. Alcoholic beverages were watered down and pub opening times were restricted to noon–3pm and 6:30pm–9:30pm (the requirement for an afternoon gap in permitted hours, lasted in England until the Licensing Act 1988 was brought into force). The law was designed to help prevent invasion and to keep morale at home high. It imposed censorship of journalism and of letters coming home from the front line. The press was subject to controls on reporting troop movements, numbers or any other operational information that could be exploited by the enemy. People who breached the regulations with intent to assist the enemy could be sentenced to death. It is estimated that almost one million people were arrested for breaching DORA rules and 11 ‘German Spies’ were executed under the regulations. Though some provisions of Dora may seem strange, they did have their purposes. Flying a kite or lighting a bonfire could attract Zeppelins, and after rationing was introduced in 1917, feeding wild animals was a waste of food.

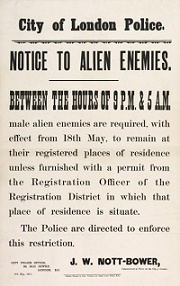

The DORA legislation was amended six times during the war, to increase social control, help prevent invasion and keep morale high. Curfews were introduced and their was censorship of letters and newspapers. Germans living in the City could be interned. Pubs shut at 11pm for the first time, and ‘treating’ or buying your friends a round of drinks was banned. New factories were built with work canteens, wash rooms for women and even creches for children of working mothers.

The DORA legislation was amended six times during the war, to increase social control, help prevent invasion and keep morale high. Curfews were introduced and their was censorship of letters and newspapers. Germans living in the City could be interned. Pubs shut at 11pm for the first time, and ‘treating’ or buying your friends a round of drinks was banned. New factories were built with work canteens, wash rooms for women and even creches for children of working mothers. Exempted trades or reserved occupations were introduced. On 27th January, 1916, there was compulsory conscription of single men, aged between 18 and 41 years. Four months later, this conscription was extended to married men. In May 1916, clocks were brought forward for the first time, to maximise working daylight hours. ‘Blackouts’ were introduced in certain towns to protect against air raids. People were fined or faced imprisonment for breaking any one of hundreds of new regulations. In Hull, fines of 10 shilling and sixpence were imposed for breaching lighting restrictions, and £5 fines were not uncommon. Though DORA met with some criticism and opposition, in general the British reaction to DORA was resignation if not acceptance. DORA was designed to represent the government’s preparedness and seriousness in response to the war, and accordingly was seen by many as a necessary sacrifice. Many of the intrusive elements of DORA were abandoned after the war, but it is interesting exploring those that were kept, including the ending of public access to railway lines and areas of sea ports.

Exempted trades or reserved occupations were introduced. On 27th January, 1916, there was compulsory conscription of single men, aged between 18 and 41 years. Four months later, this conscription was extended to married men. In May 1916, clocks were brought forward for the first time, to maximise working daylight hours. ‘Blackouts’ were introduced in certain towns to protect against air raids. People were fined or faced imprisonment for breaking any one of hundreds of new regulations. In Hull, fines of 10 shilling and sixpence were imposed for breaching lighting restrictions, and £5 fines were not uncommon. Though DORA met with some criticism and opposition, in general the British reaction to DORA was resignation if not acceptance. DORA was designed to represent the government’s preparedness and seriousness in response to the war, and accordingly was seen by many as a necessary sacrifice. Many of the intrusive elements of DORA were abandoned after the war, but it is interesting exploring those that were kept, including the ending of public access to railway lines and areas of sea ports.

10 surprising Laws passed in the First World War.

The outbreak of war in 1914 brought many new rules and regulations to Britain. The most important of these was the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), passed on 8 August 1914 ‘for securing public safety’. DORA gave the government the power to prosecute anybody whose actions were deemed to ‘jeopardise the success of the operations of His Majesty’s forces or to assist the enemy’. This gave the act a very wide interpretation. It regulated virtually every aspect of the British home front and was expanded as the war went on. Here are a few of the surprising measures introduced by DORA – some of which still affect life in Britain today.

1. Whistling. Whistling for London taxis was banned in case it should be mistaken for an air raid warning. Britons were banned from talking on the phone in a foreign language, buying binoculars or hailing a cab at night.

2. Loitering. People were forbidden to loiter near bridges and tunnels or to light bonfires.

3. Clocks Go Forward. British Summer Time was instituted in May 1916 to maximise working hours in the day, particularly in agriculture.

4. Drinking. Claims that war production was being hampered by drunkenness led to pub opening times and alcohol strength being reduced. The ‘No treating order’ also made it an offence to buy drinks for others.

5. Drugs. Possession of cocaine or opium, other than by authorised professionals, such as doctors, became a criminal offence.

6 Blackouts. A blackout was introduced in certain towns and cities to protect against air raids.

7. Press Censorship. Press censorship was introduced, severely limiting the reporting of war news. Many publications were also banned.

8. Postal Censorship. Private correspondence was also censored. Military censors examined 300,000 private telegrams in 1916 alone.

9. White Flour. Fines were issued for making white flour instead of wholewheat and for allowing rats to invade wheat stores. Further restrictions on food production eventually led to the introduction of rationing in 1918.

10. Foreign Nationals. DORA put restrictions on the movement of foreign nationals from enemy countries. The freedom of such ‘aliens’ was severely restricted, with many interned. Passports were invented to control people’s movements.

Propaganda

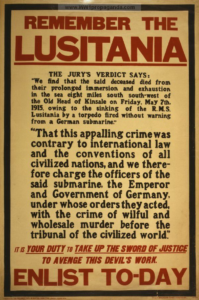

During the First World War, propaganda was employed on a global scale.  Unlike previous wars, this was the first total war, in which whole nations and not just professional armies were locked in mortal combat. This (and subsequent modern wars) required propaganda to mobilise hatred against the enemy; to convince the population of the justness of the cause; to enlist the active support and cooperation of neutral countries; and to strengthen the support of allies. Government’s tried hard to persuade people to think in a certain way. This is called propaganda. The British Government created ‘The Ministry for Information’ to produce propaganda. This was directed by the Canadian newspaper baron Lord Beaverbrook and actively influenced public opinion towards the war, using posters, news articles, and new mediums, like cinema film. For example, posters were printed that made the army look exciting. Other posters told men it was their duty to join and they would feel proud if they did.Some posters even tried to make them feel guilty, saying that their children would be embarrassed if their father had done nothing in the war. The messages were simple; support your country, support your soldiers, support your family, enlist, contribute, work. Posters were colourful and caught the eye, they were also everywhere. Storiesabout bad things the Germans had done were also encouraged. The Government knew people would be angry and even frightened. Everyone would want Britain to win the war and make the Germans pay for the dreadful things they were supposed to have done. Many of the tales were untrue. The Germans told the same stories about the British.

Unlike previous wars, this was the first total war, in which whole nations and not just professional armies were locked in mortal combat. This (and subsequent modern wars) required propaganda to mobilise hatred against the enemy; to convince the population of the justness of the cause; to enlist the active support and cooperation of neutral countries; and to strengthen the support of allies. Government’s tried hard to persuade people to think in a certain way. This is called propaganda. The British Government created ‘The Ministry for Information’ to produce propaganda. This was directed by the Canadian newspaper baron Lord Beaverbrook and actively influenced public opinion towards the war, using posters, news articles, and new mediums, like cinema film. For example, posters were printed that made the army look exciting. Other posters told men it was their duty to join and they would feel proud if they did.Some posters even tried to make them feel guilty, saying that their children would be embarrassed if their father had done nothing in the war. The messages were simple; support your country, support your soldiers, support your family, enlist, contribute, work. Posters were colourful and caught the eye, they were also everywhere. Storiesabout bad things the Germans had done were also encouraged. The Government knew people would be angry and even frightened. Everyone would want Britain to win the war and make the Germans pay for the dreadful things they were supposed to have done. Many of the tales were untrue. The Germans told the same stories about the British.

Access to the front was strictly controlled and journalists were frequently given stories and facts to publish by official press contacts; in the early years of the war, the British government for example, continually put a positive spin on the bad news from the front, casting every failed battle as a heroic last stand. To bolster public hatred against the enemy, both sides also turned to atrocity propaganda, spreading stories about rape, murder, and torture to ensure that the civilians at home continued to call for war against the “savage Huns” or “British dogs”. As the war dragged on, civilians and soldiers became increasingly distrustful of official news and the use of propaganda became subtler and more refined. By the end of the war, winning hearts and minds was just as important as winning a battle, and propaganda at a national scale became an essential prt of any military action.

Prices, Tax and Food Rationing

In Hull, income tax increased as did the number of people paying it. Whilst wages improved, many goods were more expensive and became unaffordable. Income tax increased five times between 1914-1918 and was paid by twice as many people. It would never fall to pre-war levels again. During the war, prices increased on all the basics: rent, fuel and clothing, as well as food. However, food prices increased most sharply and continuously throughout the war, sometimes at an alarming rate. Food prices overall rose by 60%, sugar, eggs and meat prices increased by 400%. Food became a growing concern for people, not just the quantity, but the quality. There were no fridges or freezers to preserve food, all food was perishable, and therefore had to be brought fresh and daily. Food became increasingly scarce due to enemy attacks on shipping and a poor harvest in 1916. These shortages provoked frustration, food queues and hoarding. Parliament announced in 1916 that there were only six weeks of food left in the country. The Government limited the number of food courses that could be served at meals in restaurants and hotels. In 1917 the harvests also failed in France and Italy. Considerable supplies of food also had to be diverted to those countries. To prevent Britain being starved into submission, the Government built more merchant ships, developed the convoy system, set up the Women’s Land Army and introduced allotments, to help increase food production. Despite appeals for people to cut down on food, potatoes, sugar, butter and margarine were in great demand and very scarce. Food rationing was introduced for the first time, in Britain, in February 1918. This started with sugar, and then restrictions on meat, butter, jam, and margerine. Cheese and tea were rationed locally. Ration coupons were issued to control rising food prices and share out limited food supplies fairly. Ration cards were issued and people registered with a local butcher or grocer. The weekly ration was set at 15 ounces of meat, five ounces of bacon and four ounces of butter or margarine. With rationing, food queues disappeared and everyone received a fair share. Prices kept high, but the threat of shortages was averted.

The Government set up 363 ‘National Kitchens’, including one in Hull, to feed people during World War One. These improved diets, cut down food waste and proved hugely popular. A bowl of soup, a joint of meat and a portion of side vegetables cost 6d – just over £1 in today’s money. Puddings, scones and cakes could be bought for as little as 1d (about 18p). These self-service restaurants, run by local workers and partly funded by government grants, offered simple meals at subsidised prices. A 1918 ‘Scarborough Post’ story about the national kitchen in Hull emphasised the ambition of the typical urban outlet: “The place has the appearance of being a prosperous confectionery and cafe business. The business done is enormous.”