Prior to WW1, women made up only a quarter of the working population. They worked mostly as domestic servants or in the textile industry. Women did not even have the right to vote. While Suffragettes campaigned hard for women’s rights, they often faced discrimination and shocking treatment by the authorities. Parliament continued to deny women the right to vote and limited female opportunities in society. When war broke out, many women immediately abandoned the struggle for the vote. Suffragettes promised that their followers would devote themselves to the struggle of winning the war. As men flocked to join the armed forces, women prepared to take their places in the work place. Their help was not welcomed at first. Only In March 1915, did the government begin to create a register of women willing to do work. Over 80,000 women

registered for war work. Even then, the Government failed to find enough work for all the female volunteers. Individual women often had to take the initiative and find work themselves. By this time, women started to be employed as drivers, police officers, and railway staff, but there was no official recognition for their efforts. In July 1915, due to the frustration at how little had been done, Suffragettes organised a huge demonstration in London, with 30,000 women demanding the “Right to Serve”. As a result of this protest, women became more involved in the war effort. Some Suffragettes helped train women to do men’s work. The socialist feminist, Sylvia Pankhurst, who denounced the first world war, set up a cost price restaurant and a mother and baby clinic in a former pub, which she renamed “the Mother’s Arms”. This would lead to the formation of local authority maternity and child welfare committees.

Demand for female labour increased and even more so after the compulsory conscription of men in 1916.

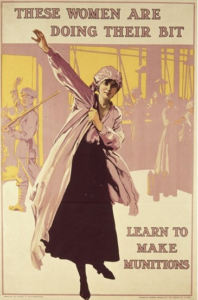

Former domestic servants became window cleaners, gas fitters and crane drivers. They moved into munitions factories, where their faces turned yellow and their hair green from the chemicals. They braved explosions and poisonous substances to serve their country and earn higher pay.

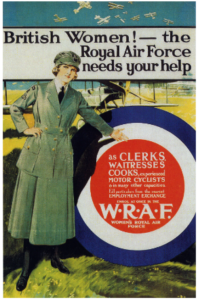

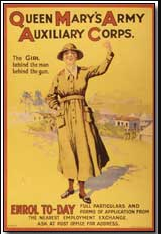

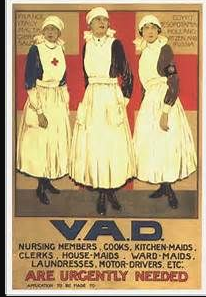

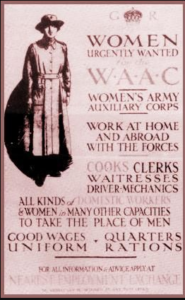

Women entered the Armed Services in 1917, in non combatant roles, so releasing men to fight. Many ‘middle class’ women joined  the Women’s Royal Air Force (WAF’s) and another 100,000 joined the Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRENS). Working Class women mainly joined the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAC’s), which later became known as the Queen Mary Army’s Auxiliary Corp. These women were largely employed in unglamorous tasks, such as communications; cooking and catering; store keeping; clerical work; telephones and administration; printing; and motor vehicle maintenance. Women also became truck and ambulance drivers as more men were called to the front line. Many joined the Women’s Land Army or Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD’s). 200,000 women took up work in Government Departments. 500,000 women took up business clerical positions. 250,000 women worked on the land to boost food production. 80,000 women served as non combatants. 700,000 women worked making shells and bullets.

the Women’s Royal Air Force (WAF’s) and another 100,000 joined the Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRENS). Working Class women mainly joined the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAC’s), which later became known as the Queen Mary Army’s Auxiliary Corp. These women were largely employed in unglamorous tasks, such as communications; cooking and catering; store keeping; clerical work; telephones and administration; printing; and motor vehicle maintenance. Women also became truck and ambulance drivers as more men were called to the front line. Many joined the Women’s Land Army or Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD’s). 200,000 women took up work in Government Departments. 500,000 women took up business clerical positions. 250,000 women worked on the land to boost food production. 80,000 women served as non combatants. 700,000 women worked making shells and bullets.

By 1918, roughly 1.5 million women had replaced men in work. They were paid much less, about 11 shillings a week on average, compared to 26 shillings per week for men. Their reward was the granting of the vote to women over 30, passed in June 1918. A more important effect was the change in women’s place in society.

The war was a liberating, and challenging experience for many women. It released women from the drudgery of domestic service, provided better paid work and allowed some to socialise with people from different backgrounds. It opened up a wider range of jobs giving women greater confidence and opportunities to show their worth.

It showed that women were more than capable of taking on men’s work and in some cases were better. Their valuable war service could not be ignored by the Government and provided women with greater opportunities for citizenship.

The War increased the female workforce. In July 1914, 5.8 million women workers made up 26% of the workforce. By January 1918 there were over 7.3 million women workers, which made up 36% of the workforce.

Women worked in munitions factories (Munitionettes), in engineering, ship building, furnace stoking, in banks, on buses and railways, in gasworks, as nurses near the battlefront and at home.

Some of these new jobs were noisy, dirty and dangerous. The use of toxic chemicals, and TNT caused bilious attacks, blurred vision, depression and jaundice. Female Munitions worker’s became known as ‘Canaries’, as the toxins that they worked with, turned their skin yellow and their hair green. At least 109 women died working with these poisonous chemicals.

The work was long and arduous. For example, the women at the Grimsby shell factory, made 6″ shells, which was on the border line for being too heavy for them. They worked shifts of 7am to 2pm, with 1.5 hour’s break, and a night shift of 10pm to 6am, with 1.5 hours break. The lack of quality control caused many industrial accidents where women were the prime casualties. For example, an explosion at the Silvertown munitions factory in West Ham, on Friday, 19 January 1917, killed 73 people and injured 400 more. It destroyed 900 homes and damaged another 70,000 local properties. Similarly, the National Shell filling Factory, at Chilwell, Nottingham, exploded on 1st July 1918, killing 137, and injured 250.

These jobs had been largely excluded from women before the war. Skilled male workers feared women would enable employers to reduce craft differentials and this indeed happened in some factories. However, the new female recruits would also assert themselves in the workplace. In July 1918, male and female munitions worker in Coventry took strike action together. In that last year of the war, when women bus and train workers went on strike, the slogan, “Same work, Same money” appeared. when the strikes spread from Hastings to Bristol, to Birmingham and South Wales, the authorities intervened with a five shilling bonus, though not equal pay. Women also asserted themselves in other ways. In 1915, the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association, led a successful rent strike against greedy landlords, which forced the Government to introduce the Rent Restrictions Act. In October 1919, Florence Farrow, a Derby member of the Women’s Co-operative Guild, suggested a state allowance for every child, better pay for teachers, along with municipal milk, housing, heating, lighting, baths and cinemas. Things now taken for granted owe much to the efforts of these unsung female activists during the First World War.

Some Inspirational Stories of Women in WW1

Hertha Ayrton (1854 – 1923), was a British engineer, mathematician, physicist, life saving inventor, and suffragette. Physicist, Hertha Ayrton was one of the first female students to go to Cambridge University, and patented an engineering drawing instrument soon after she left in 1880. In 1902, despite doing important work in her field, the Royal Society rejected her election to its membership on the grounds that she was a woman. During the war, she invented the Ayrton Fan, a device that helped soldiers clear poisonous gas from their trenches. Over 100,000 were issued to British troops and they were in constant use from May 1916 onwards.

The First World War helped improved some Women’s work conditions.

Many male workers, trade unions and factory owners were against women working in factories. Workers had concerns over dilution (using unskilled workers). They were also worried about women ‘accepting’ lower wages and taking men’s jobs away. The scale of women’s employment could no longer be denied, and rising levels of women left unmarried or widowed by the war, forced the hands of the established unions. In addition, feminist pressure on established trade unions and the formation of separate women’s unions threatened to destabilise ‘men-only’ unions.

The increase in female trade union membership from only 357,000 in 1914 to over a million by 1918, represented an increase in the number of unionised women of 160 per cent. This compares with an increase in the union membership of men of only 44 per cent. However, the war did not inflate women’s wages. Employers circumvented wartime equal pay regulations by employing several women to replace one man, or by dividing skilled tasks into several less skilled stages. In these ways, women could be employed at a lower wage and not said to be ‘replacing’ a man directly.

By 1931, a working woman’s weekly wage had returned to the pre-war situation of being half the male rate in more industries. Women were not only paid less, but promoted less and many were sacked at the end of the war. While World War One provided women with more varied work opportunities, it did not provide long-term employment opportunities. When the troops were demobilised these women were expected to stand aside. 750,000 women were made redundant in 1918 and the 1921 census reveals that there was a lower percentage of females working than there had been in 1911. However, employers could no longer argue that women were unable to undertake roles, and this change would contribute to growing equality between people in society.

Yet there were positives – women gained more freedom after the war. Women were largely free from being ‘chaperoned’ by men. Some women had better wages and skills than before, which gave them more independence and confidence. Pre-war clothing, like corsets and long skirts which restricted walking, were replaced with looser fitting garments. Clothing became much simpler and trousers became acceptable. Women shortened their skirts, bobbed their hair, wore makeup and took to sunbathing for the first time. Previously a suntan had meant you were lower class and worked outside, but now it meant that you had wealth and the leisure time for outdoor activities. Munitionettes also organised ‘Girls Night’s out’ and caused public alarm over their behaviour and what they spent their money on.

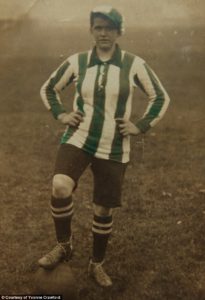

Women’s Football. When professional football was suspended in 1915, factory girl’s started their own female football leagues. These proved hugely popular, and successful.

The Blyth Spartan Munitionettes remained unbeaten during the war, with their striker, Bella Reay, scoring a record 133 goals. Unfortunately, these female football teams were disbanded after the war.

The First World War gave some women Political Rights. In recognition of women’s valuable war service, the 1918 Representation of the People Act, gave Women aged 30 or over, the Right to Vote. (men aged 21 or over were also given the vote).Women were also allowed to stand as MP’s and by November 1918, 8.4 million women were eligible to vote. However, women voters had to own property, or be married to a house owner. Women were not given the same voting rights as men, because if women had had the vote at the age of 21 in 1918, they would have outnumbered men. It was not until the 1928 Representation of the People Act, that all women over the age of 21 could vote. Women were the unsung hero’s of the First World War, keeping the industrial wheels turning and the home fires burning. Women remained largely responsible for bringing up children and caring for dependants and carried on while their love ones were being killed and wounded. Their prospects of marriage and having children declined with the numbers of men lost in the war. There was no Welfare State and the help and support available was limited. Even with these pressures and their new war duties, women still found the time to write to those fighting on the front line. Their letters, parcels and mementos helped boost the morale of their homesick and frightened men. Women dealt with the trauma of air raids, which were a new and terrifying experience. Even more traumatic, was the painful process of readjusting to the return of loved ones from the battlefields. Hundreds of thousands of men returned from the war, injured in some way. Women bore a large part of the burden of caring for these men. Even worse, women lost their fathers, husbands, lovers, brothers, and sons. For these women, life would never be the same. Despite the vote, few female candidates would make Parliament and would prove difficult to promote women’s rights, and women issues shuffled down the agenda. A major obstacle was post war unemployment, which forced many women back into domestic service and low paid jobs in sweated industries. As the decade came to an end, much of what women had done in the war faded from immediate memory. In the years to come, unemployment, grinding poverty, the rise of fascism and another war were to muffle the post war dreams of freedom, fulfilment and equality for women.

In Memory of Nurse, Florence Caroline Hodgson, 50499, Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps, died 1st November 1918, aged 32. Daughter of John Frederick & Rose Ann Hodgson, of 47 Lee Smith Street, Hull. Buried at Hedon Road Cemetery, Hull.

In Memory of Nurse, Florence Caroline Hodgson, 50499, Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps, died 1st November 1918, aged 32. Daughter of John Frederick & Rose Ann Hodgson, of 47 Lee Smith Street, Hull. Buried at Hedon Road Cemetery, Hull.

Teachers in the First World War; http://www.ww1schools.com/teachers-at-war.html

Women at Work Photos; http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2411052/Incredible-photos-shed-light-working-life-Britains-women-First-World-War.html

Women’s lives in World war One; http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01p329t