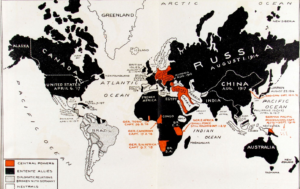

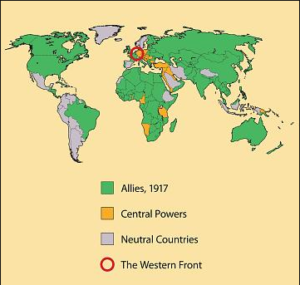

The First World War was the first truly global conflict. Between 1914 and 1918, more than 100 countries from Africa, the Americas, Asia, Australasia, and Europe were part of the conflict in some form. The British Army alone consisted of troops from six different continents: Europe, North America, South America, Australasia, Asia and Africa. The war was fought throughout the world, on land, sea and air in Northern France & Southern Belgium, Italy, the Balkans (including Greece & Gallipoli); Russia; Egypt; Africa; Asia and Australasia. Huge armies deployed new weapons to devastating effect, including tanks, airplanes, submarines, machine guns, heavy artillery, flame throwers and poison gas. Over nine million soldiers and seven million civilians lost their lives. Empires crumbled, revolution engulfed Russia, and America rose to become a dominant world power. It was the start of modern history. It resonated for decades after. We still live with its consequences today in the Middle East and Northern Ireland.

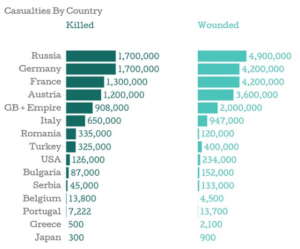

The impact of war can be measured in many ways, such as the cost in lives, the financial costs and the consequences the war had on future world history. In terms of statistical casualties, and lives lost, the First World War was the fifth most costly war in World history. All told, 70 million were mobilised, 16.5 million people died and 21.2 million were wounded from all combatant nations during World War 1. We will never know the true extent of civilian casualties, who perished through occupation, bombardment, hunger and disease . They include those lost in occupied countries, such as Belgium and France, the victims of atrocities in Serbia or Russia or the numbers of Armenians exterminated in Turkey, those lost through starvation and malnutrition. The losses are further distorted by the Influenza epidemic in 1918, which killed another 20 million of the world’s people and soldiers who were weakened by war.

The Cost in Lives

From 1914 to 1918, Britain and Commonwealth forces lost nearly 900,000 military personnel and 1.7 million men were wounded. In Britain that was about 10% of all men serving killed, and many of these were young men, with 70% of those killed, aged between 20 – 24 years old. Scotland which traditionally provided recruits for the British army’s elite regiment’s, lost 148,000 men. This was 25% of those that volunteered and more than twice the national average rate of fatalities for the whole of Britain. Over 38,000 Irishmen and 20,000 Welshmen also died in the war. Throughout the United Kingdom, one in six families suffered a direct bereavement, 192,000 wives had lost their husbands, and nearly 400,000 children had lost their fathers. A further 500,000 children had lost one of more of their siblings. Appallingly, one in eight wives died within a year of receiving news of their husband’s death.

From 1914 to 1918, Britain and Commonwealth forces lost nearly 900,000 military personnel and 1.7 million men were wounded. In Britain that was about 10% of all men serving killed, and many of these were young men, with 70% of those killed, aged between 20 – 24 years old. Scotland which traditionally provided recruits for the British army’s elite regiment’s, lost 148,000 men. This was 25% of those that volunteered and more than twice the national average rate of fatalities for the whole of Britain. Over 38,000 Irishmen and 20,000 Welshmen also died in the war. Throughout the United Kingdom, one in six families suffered a direct bereavement, 192,000 wives had lost their husbands, and nearly 400,000 children had lost their fathers. A further 500,000 children had lost one of more of their siblings. Appallingly, one in eight wives died within a year of receiving news of their husband’s death.

There were also 1.7 million British wounded, of which 80,000 were gas victims, 30,000 were made deaf, 80,000 had ‘shell shock’, and there were 250,000 amputees. The wounded increased over time. At the end of 1928, nearly 2.8 million war veterans were receiving a war disability pension. There were still 65,000 soldiers in mental hospitals by 1929. Millions of men had been uprooted and taken away from home for the first time. They were exposed to new vices, like alcohol, violence, tobacco, profanity and prostitution. There were over 400,000 venereal disease cases treated during the war, which would have emotional and physical consequences for soldiers of all ranks and their families.

Death in the the First World War caused untold psychological casualties. These were both soldiers and civilians, who either saw death personally, or suffered a profound loss of a loved one. The huge numbers of casualties, over a four year war, was both shocking and unprecedented, in the twentieth century. Almost every family had lost someone they knew. Death in this new industrial warfare, could be anonymous, indiscriminate, random and bizarre. Men were sniped, machine gunned, shelled, bombed, bayoneted, mortared and burnt alive. They were kicked by horses, electrocuted by generators, suffocated by charcoal braziers in winter dug outs, or drowned in mud. They died in accidents, during training or succumbed to illness and disease. One NCO died of a heart attack behind the lines before the start of the battle of Loos. A military policeman was shot dead by a deserting officer, who himself was executed for the crime. A few were executed by their own comrades. Some died suddenly, and peacefully, while others died in pain and terror. Such deaths could not be easily understood, or explained, or even dealt with, by those who grieved. Civilian soldiers, who had volunteered for war, were not trained to deal with this trauma psychologically. For many, the haunting memories of terrible battles and lost friends, would emotionally scar them for life, and their families.

With so many men blown to pieces and missing abroad, most families were denied the opportunity to visit a local grave. (Britain did not repatriate their war dead and this was strictly enforced from Spring 1915). There was no welfare state, or modern counselling, to advise people how to deal with their grief. Many families had to live with bereavement, depression, and sorrow, and make do, the best they could, on their own, with limited support. The way people processed their emotions would vary across, class, region, gender and religion.

Britain’s Upper Classes suffered disproportionately worse, with some 25% of Officers killed and wounded, as opposed to 8% of working class casualties during the war. The decimation of the ‘Pal’ Battalions, particularly affected Northern towns and cities. Scotland suffered the highest proportion of war casualties. Middle class women were more likely to write about their bereavement and express their feelings in correspondence and commemorations. They left a number of books, letters, church plaques and other memorials, as a poignant reminder on how war devastated family life. A good example of this, is Vera Britain’s memoir, Testament of Youth, which spoke for a generation, about the losses of war.

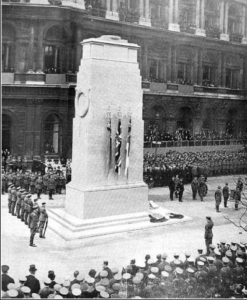

Britain also became a more secular country. Church attendances began to fall, as people struggled to reconcile their losses with their religion. They turned to new faiths, like ‘Spiritualism’, to reconnect directly with their dead. The First World War profoundly changed British social attitudes towards bereavement, mourning and commemorating death. The ritualised mourning of the Victoria era, with the ‘deathbed’ scene, surrounded by loved ones, was no longer possible. To preserve public morale, expressions of open sorrow, were discouraged. Private funerals were replaced with more public ceremonies for the dead. These included the creation of new rituals, like the Cenotaph, the ‘Tomb of the Unknown Warrior’, Armistice day, the wearing of poppies, and the very public ‘two minute’ silence. There was demand from civilians for battlefield tours and organised pilgrimages. The First World War began the first package holiday for the masses. We will never know how many lives were blighted by the experiences of the First World War. Although literature and family stories, handed down, tell a time, of great sorrow. We can only speculate on the the sufferings of orphans, war widows, and the disabled servicemen who struggled to cope. The war experience would impact on family life, leading to alcoholism, violence, organised crime, and increasing suicides in the following decades. Many veterans were left with depression, anxiety and untreated madness. Some 65,000 British soldiers were still living in mental institutions by 1929.

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/bereavement_and_mourning_great_britain

The loss of 750,000 young men during the war, and nearly 2 million wounded, affected Britain’s demographics. After the war, women far outnumbered men and many women were never to marry or have children. The 1921 United Kingdom Census found 19,803,022 women and 18,082,220 men in England and Wales, a difference of 1.72 million, which newspapers called the “Surplus Two Million Women.” In the 1921 census, there were 1,209 single women, aged 25 to 29, for every 1,000 men. In 1931, 50% of these women were still single, and 35% of them did not marry while still able to bear children. Many women after the war emigrated to Commonwealth countries, in search of a new life. However, the losses to the Commonwealth nations that supported Britain were also severe. In all, 250,000 killed and 500,000 wounded. New Zealand lost 18,000 killed and 50,000 wounded out of the 112,000 who served. This was a casualty rate of 66%. Australia’s casualties were 80,000 killed and 137,000 wounded, 64% of those who enlisted. Similarly, Canada and Newfoundland lost 62,000 and 172,000 wounded, a casualty rate of 39%; South Africa lost 7,000 killed and 12,000 wounded, 13% of those who served, and India, who provided more Commonwealth troops, than all the others put together, suffered 74,000 killed, 67,000 wounded, or 7% of those that served. In addition, it is estimated that 100,000 men from the African and Caribbean Colonies, who acted as carriers and labourers, died of disease and exhaustion, with another 18,000 killed in action.

In France, where much of the war raged, approximately 11% of the entire population, was killed or wounded during the war. Almost 1.4 million Frenchmen died in the service of their country and another 4.2 million men were wounded – a casualty rate of 74% of all those mobilized in the French Empire. They left behind 600,000 widows, 986,000 orphans, and 1.1 million war invalids. Ten percent of the male population of France had been wiped out, a figure that rises to 20% for the ‘under 50’ age group. Of the 470,000 males born in France in 1890, and who were 28 years old when the war ended, half were killed or seriously wounded. Some 7.5 million acres of French land had been destroyed by explosives and chemical warfare. The Western Front along 250 miles and 25-30 miles wide had been reduced to a wasteland. 1,659 towns and communes had been blotted out, 2,363 others were wrecked, and 630,000 houses were destroyed or seriously damaged. So many mines were ruined, that the output of coal was reduced by a half, 21,000 factories were gutted, and the great manufacturing centres at Lille, and the Longwy district, were systematically despoiled of machinery vital to their prosperity. Deaths of civilians by artillery in the battle zone, or in the back areas by aircraft were frequent. Deaths continue today, due to unexploded munitions in the Western front area.

The total number of First World War deaths includes about 10 million military personnel and about 7 million civilians. The Entente Powers (also known as the Allies) lost about 6 million soldiers, while the Central Powers lost about 4 million. At least 2 million died from diseases and 6 million went missing, presumed dead.

The youth of Europe was decimated. Of the 700,000 British war dead, no fewer than 71% were between the ages of 16 and 29 years. The CWGC records, show that 14,108 British soldiers, were aged 18 or younger, when they died. In Belgium more than 40,000 young men were killed.

About two-thirds, of military deaths in World War I were in battle. This was unlike any previous conflict during the 19th century, when the majority of deaths were due to disease. Improvements in medicine, as well as the increased lethality of military weaponry were both factors in this development. Nevertheless disease, including the ‘Spanish flu’, still caused about one third of total military deaths for all belligerents.

Financial Cost of World War One

World War One cost the world over $3.8 Trillion dollars (This was mostly made up by Germany, $984bn, Britain, $1,205bn, France, $641bn and America, $787bn). Britain paid the most, and funded the war by selling off foreign investments and borrowing heavily from the United States. This effectively ensured that America remained an ally throughout the war, and the USA became the richest power afterwards. In the United Kingdom, funding the war had a severe economic cost. From being the world’s largest overseas investor, Britain became one of its biggest debtors, with interest payments forming around 40% of all government spending.

World War One cost the world over $3.8 Trillion dollars (This was mostly made up by Germany, $984bn, Britain, $1,205bn, France, $641bn and America, $787bn). Britain paid the most, and funded the war by selling off foreign investments and borrowing heavily from the United States. This effectively ensured that America remained an ally throughout the war, and the USA became the richest power afterwards. In the United Kingdom, funding the war had a severe economic cost. From being the world’s largest overseas investor, Britain became one of its biggest debtors, with interest payments forming around 40% of all government spending.

Inflation more than doubled between 1914 and its peak in 1920, while the value of the Pound Sterling fell by 61.2%. Reparations in the form of free German coal depressed local industry, precipitating the 1926 General Strike. The Versailles Treaty set German repayments for the cost of the war at 132 Billion Marks. This was to be repaid in cash or raw materials, land given up and services provided. These repayments were suspended in 1932, by which point Germany had repaid 20.5 Billion Marks (about $6 billion).

British private investments abroad were sold, raising £550 million. However, £250 million in new investment also took place during the war. The net financial loss was therefore approximately £300 million; less than two years investment, compared to the pre-war average rate and more than replaced by 1928. Material loss was “slight”: the most significant being 40% of the British merchant fleet sunk by German U-boats. Most of this was replaced in 1918 and all immediately after the war.

The most enduring legacy of the war was increased censorship and state control over people lives. Even in free market Britain, the Government’s share of the economy rose from 9.8% of GDP in 1913, to over 37% by 1918. In Germany, the Government was responsible for 59%. of all output. The need to win the war, meant that the State increasingly regulated the activities of private citizens. Government’s rationed food, banned strikes, censored newspapers, controlled private property, wages and taxation. They effectively dictated what people did, said, read and thought. Many of these rules, censorship and legislation, continued long after the war. Yet for all the sufferings and restrictions, ordinary people found a new voice. Women enjoyed new freedoms and began to demand the vote. Trade Union membership grew. Soon the deference to the ‘Officer Class’ would be eroded and replaced with more democratic forms of Government. State intervention was tolerated, but with the expectation of better schools, housing and health care.

The Commonwealth Nations

Abroad, there was growing assertiveness amongst Commonwealth nations after World War 1. Battles, such as Gallipoli, for Australia and New Zealand, Hill 70 and Vimy Ridge, for Canada, Deville Wood for South Africa, and Neuve Chapelle for Indian Troops, led to increasing national pride and identity. There was a greater reluctance to remain subordinate to Britain, leading to the growth of diplomatic autonomy in the 1920’s. Loyal dominions, such as Newfoundland, were deeply disillusioned by Britain’s apparent disregard for their soldiers, eventually leading to the unification of Newfoundland with the Confederation of Canada. Colonies, such as India and Nigeria, also became increasingly assertive because of their participation in the war. The populations in these countries became increasingly aware of their own power and Britain’s fragility. In Ireland, the delay in finding a resolution to the ‘Home Rule’ issue, partly caused by the war, as well as the 1916 Easter Rising and a failed attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland, increased support for separatist radicals. This led indirectly to the outbreak of the Irish War of Independence in 1919. The creation of the Irish Free State that followed this conflict, in effect represented a territorial loss for the United Kingdom, that was all but equal to the loss sustained by Germany, (and furthermore, compared to Germany, a much greater loss in terms of its ratio to the country’s pre-war territory).

The Cultural Impact of the War

Britain spent four and half years fighting the First World War and the next 100 years trying to understand it’s meaning and purpose. There are so many myths, opinions, politics and propaganda surrounding World War One, that we no longer know what we feel about it, or even if we should celebrate it. Was the ‘Great War’ a triumph, or an unspeakable horror? Do we side with the War Poets or the Politicians? We can not even agree how World War One should be taught in schools today. It has been a cultural battlefield for every generation that followed it. British attitudes to the Great War have varied and changed over time and even different countries remember World War 1 in different ways.

The following is a brief summary of Britain’s changing views of World War One.

Numbed by this great loss of life and uncertainty about the war, the British establishment, that had sent so many men to their deaths, assumed control of the war dead. A whole raft of institutions and ceremonies were created to commemorate the dead, which still survive today. The ‘Commonwealth War Graves Commission’ was established to ensure that all the fallen, were remembered by a war grave, or a memorial near the battlefield. In 1914, Sir Fabien Ware, who had been a commander of a Red Cross Ambulance unit, began to document the locations of soldiers graves near the front line. His continued efforts ultimately led to the establishment of the Imperial War Graves commission in May 1917. Fabien Ware also designed the white military headstones, that we see in war cemeteries today; and he designed many war cemeteries and war memorials over the next 20 years, using the great architects of the day. The Poet, Rudyard Kipling, selected the phrase “Known unto God“, which was to be inscribed upon these white tombstones. The phrase ‘Lest we Forget‘ also comes from the Kipling poem, “Recessional“, and is used as the wording on many memorials, as a plea not to forget past sacrifices. Kipling also worked with Winston Churchill to ensure that all gravestones were uniform, the same shape and size, regardless of military rank. The rows of white, matching gravestones, lining military cemeteries are their legacy. Sir Edwin Lutyens designed the Whitehall Cenotaph, as a national memorial to the war’s dead in 1919. Prime Minister, Lloyd George, chose the inscription ‘The Glorious Dead’, which was carved on the Cenotaph; Earl Haig, the Commander of the British forces, founded the British Legion in 1921, to give ex servicemen a voice. An ‘Armistice Day’ was initiated to be held on annually on the 11th November, the day war ended. The South African, Percy FitzPatrick, suggested a ‘Two Minute Silence’ at 11am on every Armistice Day, so that “in perfect stillness, the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the glorious dead.” The tradition of wearing red poppies was then established to remember the nation’s ‘Glorious Dead’.

Such was the nation’s catastrophic loss, politicians renamed the 1914-18 conflict, as ‘The Great War‘, or the ‘War to End All Wars‘. Civilian views of the war remained mixed and confused for decades to come. Many of those who had lived through the war, felt that they had survived a great, world event, and were proud to remember the sacrifice, hardship and heroism. Initially, there was much relief and celebration. Armistice Day, for example, became a ‘restaurant bonanza’ and many surviving veterans celebrated their comradeship and war time experiences. Others however, struggled to make sense of the war. They were traumatised by their experiences. Sorrow and bereavement would haunt nations for generations. Over time, more people saw the war as a futile waste of lives and an end to world stability. Most opinions were framed by war time propaganda and the Politicians and Poets of the time. Many civilians had known little about the war or the true horrors of the fighting. There was no television, news channels or social media, to communicate the war then. The silence of the returning war veterans only added to the Great War’s mythology. The ‘Cenotaph’ was successful and long lasting, because in some way it provided a blank canvass for people to project their mixed feelings about the war.

In 1928, on the 10th anniversary of the ending of the Great War, Britain again reflected on the War experience. West End Plays, like RC Sheriff’s, ‘Journey’s End’, and the publication of many memoirs, such as ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’, ‘Cry Havoc’ and ‘Death of a Hero’, revealed the true horrors of the Great War, to a mass civilian audience, for the first time. The stories of terrible sacrifice, and pointless slaughter prompted a revulsion to war. A British pacifist movement starting in the 1920’s, grew increasingly during the 1930’s. Some campaigned for disarmament and economic sanctions against military aggressors. Others campaigned for appeasement. Many organisations, such as the ‘No More War Movement’ and the ‘Peace Pledge Union‘ were established to totally denounced war. This was to leave Britain very unprepared, in 1939, when the next World War began. After the Second World War, the British Government in 1948, renamed the ‘Great War’ as the ‘First World War’, to distinguish it from the ‘1939-45 Conflict’. ‘Armistice Day’ was also replaced with ‘Remembrance Sunday‘, to remember those lost in all wars, and not just those of the First World War. These changes were significant. It highlighted that the the Great War, was not the ‘War to End all Wars’ and made people re-evaluate the purpose of the World War 1.

The 1960’s generation shaped our view of the First World war again. 1964 was the Great War’s 50th anniversary. It was a chance for a new generation to discover World War One afresh. However, they viewed the war through the tinted nightmare of World War Two and the possibility of a new nuclear war with the ‘Cuban Missile Crises’. The 1960’s generation was far more egalitarian and less deferential. They mocked the attitudes of their predecessors, and were more interested in the individual experiences of ordinary soldiers, rather than the posturings of upper class politicians and generals. The release of the 26 part, television documentary, ‘The Great War‘, brought a ‘dead’ conflict to life. Books like Alan Clarke’s ‘The Donkeys‘ was a scathing examination of British Generals. Plays like ‘Oh What a Lovely War‘, savaged the futility of war and also satirised the class war within it. Academics revised WW1 further, arguing that ‘The Great War’, was a war with no moral justification, or clear cause. Its pointless carnage was only illuminated by the rediscovery of the long forgotten war poets. These war poets defined the war for an Anti War 1960’s generation. Carefully edited selections of war poetry were repackaged, showing a poetic learning curve from Rupert Brook’s innocent patriotism, to Siegfried Sassoon’s angry satire and then Wilfred Owen’s bleak pity and horrors of war. The fact that Wilfred Owen had won the Military Cross for enthusiastically machine gunning the enemy, was conveniently forgotten and his war letters and diaries were doctored to airbrush these memories. Britain’s obsession for the soldier poets, shaped how World War One was taught in schools for decades and how the war would be publicly remembered. The Great War would now be defined by the horrors of trench life on the Western Front. The ‘Blackadder Goes Forth‘ comedy series, which lampoons incompetent Generals, has been used as a teaching aid in schools. It still echoes public perceptions of the First World War, as a war of futile attrition fought by Britain in trenches, on the Western Front. It ignores the fact that all not all Generals were bad (200 Generals from all sides were killed, wounded and taken prisoner in the front line). Generals undoubtedly made catastrophic mistakes, but they were largely doing the best that they could in rapidly changing new type of warfare. The Great War was a also global war, fought not just on the Western Front between the allies and Germany, but by many nations, on land, sea and air, throughout the world. The war in fact was won not just by soldiers on the battlefield, but by civilians in the factories at home. By the end of the war, the Allies were maximising resources and out producing the enemy, in every war winning technology – planes, heavy guns, tanks and ships. The Allies were also evolving new weapons and sharing new tactics to use these weapons more effectively. The Allies had more manpower than the Central Powers. They had learnt to share their war time responsibilities and could co-ordinate their efforts better than Germany. The Allies in 1918, included America with the most money, France with the biggest army and Britain with the largest Navy, which increasing blockaded the Germans and overwhelmed Germany into submission. WW1 was the first modern war won in the factories as well as on the battlefields. It showed that those who could outproduce the enemy would ultimately triumph. A lesson repeated successfully in the Second World War.

The Legacy of the Great War

While the meaning of the Great War has changed over time, it is possible after 100 years to take a more balanced view. It is becoming accepted that the Great War was not a ‘bad’ or ‘unjust’ war, at least from an Allied point of view. It was fought against German military aggression and to protect the sovereignty of small states like Belgium, as well as the integrity of British power. What went wrong was the bad peace that followed. We can now remember the scale of sacrifices made at the time, without allowing any doubts about the justice of the war, preventing our respect for the fallen.

The legacy of the Great War still resonates. In Britain, the war helped postpone the considerable domestic strife of 1914. This included increasing industrial strikes, demands for Independence in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and growing Suffragette militancy. The Great War forged a national identity, which helped sustain the British people through the Second World War and kept the United Kingdom, united for another 50 years. However, the memory of the Great War and its casualties, also made Britain very wary about Europe. It would not be until 1973, that Britain joined a European Union, and Britain is still divided over whether it should remain a part of Europe today. For the first time, the war forced British Government’s to intervene in the daily lives of individuals, on a mass scale. Successive generations would come to expect their Governments to expand these powers and responsibilities, and manage national health, welfare and taxation. The war also extended democracy with millions of British Servicemen given the vote for the first time. Some women also achieved more political rights through the First World War. The Great War generated a quantum leap in industry, technology, medicine, culture and international politics, which have all benefited society and daily life in some way.

Although, the First World War did not resolve the problems that had started it, it had a profound change on World history. It firstly contained German and Austrian militarism, (if only for a short time). It moved Europe from an age of Empire, to an era of new Nation States and fledgling democracies. It gave Eastern Europeans their independence and freedom. It gave a sense of ‘National Identity’ to Australia, New Zealand, Canada and India. It helped Russia become the world’s, first, Communist State and also launched America as a World Super Power. The ideas for which the war was fought over, also endured – Democracy and Liberalism, religious faith and Nationalism. It inspired a ‘League Of Nations’, a forerunner to the United Nations, as a mechanism to resolve international conflict and promote world peace. The League of Nations may have prevented a Second World War (1939-45), if America had remained part of it? Instead, President, Woodrow Wilson, who had proposed the League of Nations, allowed America to withdraw its’ support. Without the United States backing, the League of Nations was powerless to intervene and prevent the rise of fascism. In hindsight, we know that the First World War haunted those that experienced it. The humiliating Versailles Treaty, which punished Germany, would sow the seeds for revenge and the Second World war. From this realignment of Powers after World War 1, new ideas emerged. The ideologies of Communism, Republicism and Fascism flourished after the Great War and dominate the Twentieth Century.

The First World War resolved few of the grievances that started it. We still live with its unresolved consequences with the troubles today in Northern Ireland, the Balkans and the Middle East. The ‘Great War 1914-18’ was not the ‘War to End all Wars’ – It left dangerous loose ends, and bequeathed the world a terrible message, – that ‘Global War can affect change’, that ‘Global War can fulfil personal ambitions’, and that ‘Global War can work’. Individuals, like Adolf Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, would rework these lessons, causing great human suffering. Modern dictators and extremists of all kinds, still believe that Global War can work for them.