During the First World War, Hull was a much smaller, more crowded city, than it is today. Most people lived in the City Centre or were crammed around the fish docks of Hessle Road and the warehouses of Wincolmlee. In 1914, Hull’s population was around 300,000 people, a much larger number than the 248,000 now. The cities boundaries were tightly constrained. West of ‘Alliance Avenue, Exmouth Street, and Carlton Street’ were open fields. Spring Bank largely ended at Walton Street and along Willerby Road was open country side. North of Cottingham Road and Clough Road were also open fields. There was only a small housing development around St Johns Newland church with Wellesley Avenue being the further point North of Hull. Along Holderness Road, there was not much housing beyond Portobello Street. Housing largely ended east of Newbridge Road and Lee Smith Street. The present day housing estates of Bransholme, Orchard Park, Greatfield, Longhill, and Ings Road were then just farms. Bilton, Preston and Marfleet were separate villages.

In 1914, there were just 66,090 Hull homes, compared to 110,000 today. 80% of these were classified as ‘working class’ type, with a rent not exceeding £26 per year.

Only 28,400 homes were regarded as satisfactory, with adequate light and air circulation and having a yard or garden at the rear with a secondary means of access.

Only 9,881 or 15%, of Hull homes had inside toilets (1912 figures). Many houses lacked a rear entrance and occupants had to carry their ‘night soil’ out through the dwelling. By the outbreak of war, there were approximately 300 registered Lodging Houses. These included the Dockers’ Home in Trippett Street, which could accommodate 77 men, in separate ‘cubicles’, and the Salvation Army Lodging House, in Chapel Lane, with bedrooms for up to 130 men. The largest lodging house was Victoria Mansions, in Great Passage Street, which provided separate ‘cubicles’ for 494 working men and had a restaurant and barber’s shop within the building. Some 597 canal boats were also registered as family accommodation. Over 740 homes were recorded as keeping up to 2,850 pigs. The many docks and ships moored in the City Centre at Queens Gardens, meant many Hull houses were plagued by rats and vermin. Few properties had electricity and the smoke from domestic chimneys, factories and coal fired ships polluted the atmosphere. The lack of natural sunlight produced a serious vitamin ‘D’ deficiency in the general population.

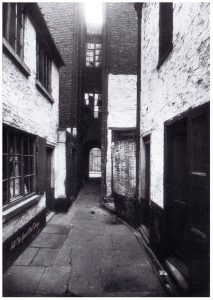

Some 21,800 properties, mostly ‘Terrace’ type housing were unsatisfactory, built at a high density of 60 houses per acre, compared with an average of 7 houses to the acre for Hull, as a whole.  Many of them were in the older working class neighbourhoods, and were four or five roomed houses, built in “Terraces”. They led off from the main streets, with between ten to thirty houses in each terrace. The structural conditions within this group of houses varied considerably. Many had rear external walls, of only four and half inches thickness, whilst a very large number were congested at the rear and had no secondary means of access.

Many of them were in the older working class neighbourhoods, and were four or five roomed houses, built in “Terraces”. They led off from the main streets, with between ten to thirty houses in each terrace. The structural conditions within this group of houses varied considerably. Many had rear external walls, of only four and half inches thickness, whilst a very large number were congested at the rear and had no secondary means of access.

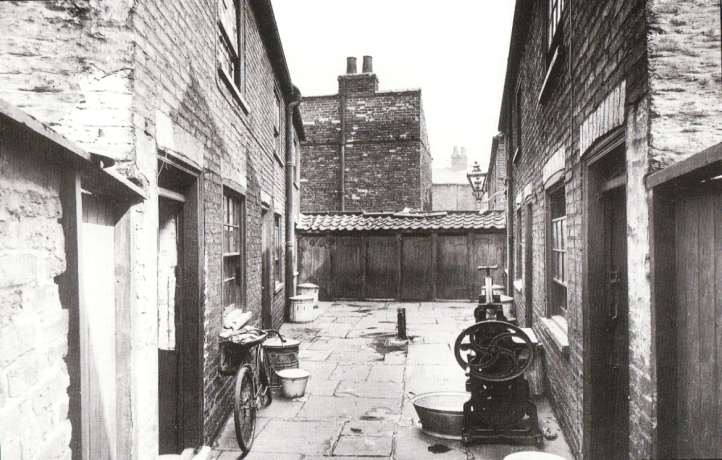

There were also about, 2,800 slum houses in Hull, which were old, damp, poorly built and situated in congested districts. Tenants invariably shared a single tap and outside toilets, which were situated together in a communal courtyard. They had thin walls, had no damp-proof course and lacked adequate light and ventilation. The only water tap was usually located in the area of the court and was shared by all the court inhabitants. The sanitary conveniences were also located within the court area and in many cases had to be shared by the occupants of more than one house.

There were about 500 houses in Hull which backed on to factories, and therefore had no through ventilation. There were also a large number of insanitary cellar dwellings and kitchens. Filth and dirt, was rife and not only infected living conditions, but transmitted illnesses, far beyond their location, through the agency of flies, water supplies and defective drainage. The collection of dry refuse by Hull Corporation did not begin until 1901 and the building of indoor water closets did not start until 1903.

Over 98% of Hull people rented their homes rather than owned them, (which was typical in Edwardian Britain). The homes were largely poor and basic, with little choice, but the rents were cheap. People preferred to live near their place of work and not commute long distances. With no Welfare state and few Council houses, people preferred to live in tightly knit communities, where they could support each other or have access to shops and facilities. For the few and wealthy, home ownership outside the Hull centre, was the most desired and affordable option. Newspapers in 1914, advertise a 3 bed house for sale in Anlaby Park for £415 – £435, and 4 bed houses for between £529 – £550. After the war, a typical 3 bed, semi-detached house, sold for between £540 – £740. A typical “sham” four roomed house, consisting of a living room, scullery, two bedrooms and bath, but without hot water, was rented in 1914, at five shillings and sixpence per week.

Poor Housing was one of the major health problems facing the City. Many houses were erected with speed, on ill-prepared sites to meet the urgent demand for accommodation from a rapidly increasing population. There was almost no accommodation specifically for the elderly, or adapted housing for the disabled and very few homes solely for women.

While Hull had an overcrowded City Centre, the worst living conditions were to be found in Hull’s dock area. Many working class families were crammed into poorly built court houses, often 12 people to a house and different families sharing the same room. These ‘homes’ were old, damp, with insufficient light and ventilation, without back ways and crowded together.

They were uncomfortably hot in summer, bitterly cold in winter and had no direct water supply. Toilets were inadequate and had to be shared by households in the same street. Rubbish stagnated in unpaved streets. The Eastern Daily News published a report in 1883, which compared the streets off Hessle Road, with the ‘foulest slums in Constantinople’. It reported houses “had no furniture and everywhere animals and humans lived together, with sewage flowing from outdoor privies and forming pools in the street.”

Disease

Severe overcrowding and squalid living conditions put Hull’s health at great risk. Outbreaks of diseases, such as small pox, typhus fever, diphtheria and tuberculosis were common. Some, like the Cholera epidemic in Hull in the summer of 1849, lasted 3 months and killed 1,860 out of a population approaching 81,000. Of those who died, 1,738 were recorded as belonging to the ‘labouring classes’ and 40% from the Hessle Road area. By the close of 1871, 23% of Hull children died before the age of one, and 45% died before the age of 12. By 1914, 121 out of the registered 960 Hull births still ended in infant mortality – a rate of 12%. Most children were artificially fed and did not attend infant welfare clinics. They invariably died of diarrhoea, and of ‘rickets’, a disease characterised by poor nutrition, with a softening and deformation of bones. Infant mortality was largely related to improper feeding, poor education, ignorance, negligence and indifference on the part of their guardians. The outbreak of war in 1914 interfered not only with the development of the school health service in Hull, but also with the expansion of services for infants and the pre-school child.

Housing and new Homes for Heroes

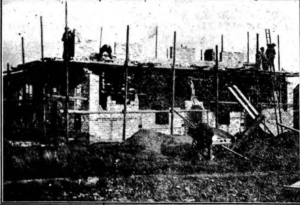

There was a severe shortage of housing in Hull. War time conditions had prevented new house building and allowed only the minimum of essential repairs. As a result, the general standard of housing in 1919, was well below that of 1914. It was estimated that in 1919, Hull required a total of 5,000 new houses to meet the arrears over the period of the war. A further 2,578 were needed to rehouse people living in unhealthy areas, and another 200 to rehouse those living in individually, unfit houses, in different parts of Hull.

The 1919 (Addison) Housing Act helped established Hull’s first Housing Committee and made the Council the chief provider of new housing. As a start towards meeting this shortage of 7,778 houses, Hull City Council purchased three areas of land on the northern, western and eastern outskirts of the City to erect housing estates. These became known respectively as the Bricknell Avenue, Gipsyville and Preston Road estates and house building began in the 1920’s. On most estates, Council houses were provided with a generous sized garden to encourage tenants to grow their own vegetables, a privet hedge at the front and an apple tree at the back. The interiors varied, some having a parlour, but all with a scullery and bath. For most new tenants, these new conditions were a huge improvement on their previous slum housing, where they had experienced overcrowding and often lacked basic facilities. The quality of the new housing was generally high. Although some slum clearance took place during the 1920s, much of the emphasis of this period, was to provide new general needs housing, on greenfield sites. The new houses had electricity, inside toilets, fitted baths and front and back gardens. The Council had strict rules for new tenants on housework, house and garden maintenance, children’s behaviour and the keeping of pets.

The 1919 Housing Act, made housing a national responsibility, and local authorities were given the task of developing new housing and rented accommodation where it was needed by working people. The 1919 Housing (Addison) Act (named after Dr Christopher Addison, the Health Minister) was passed initially as a temporary measure. It was to help meet housing need, when private builders could not meet the demand. It was generally assumed that the private sector would resume responsibility for working class housing once the British economy had recovered. The 1919 Act provided 213,000 new Council homes across the country. Although insufficient to meet the National need, it was a marked increase on the 24,000 ‘social’ homes that existed in 1914.

The most ambitious housing estate, built to reward soldiers and their families after the war was the massive Becontree estate in Dagenham. It was to become the largest council housing estate in the world. Work by the London County Council started on the estate in 1921. Farms were compulsory purchased and by 1932, over 25,000 houses had been built and over 100,000 people had moved to the area. The new houses had gas and electricity, inside toilets, fitted baths and front and back gardens. The estate expanded over the Essex parishes of Barking, Dagenham and Ilford with nearly 27,000 homes in total creating a virtual new town with dwellings for over 30,000 families.

Private House Building – Godfrey Mitchell, a demobbed Royal Engineer Officer, that had served in France, acquired the Wimpey Home Construction business and built many private homes in Hull during the 1930’s. The Woolwich Building Society lent 90% mortgages and allowed people for the first time to buy their homes. After the war, a typical 3 bed semi-detached house sold for between £540-£740. Buyers needed a 5% deposit, with repayments at around 26 shillings a week and buyers were given a Government subsidy of £50 as a further incentive. Most of Hull”s new council estates, provided good quality housing for the better off, working classes, but did not provide a solution for the poorer people in society. Rents were relatively high and subletting was forbidden, so naturally the tenants in the best position to pay were selected. High rents sometimes meant difficulty in paying, as more applicants from unskilled occupations were housed.