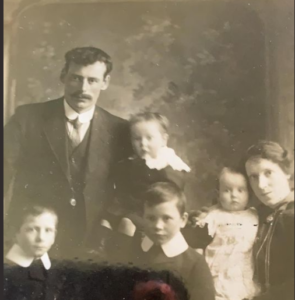

During the First World War, Hull was a much smaller and densely populated City, than it is today. Most people lived in the City Centre or were crammed around the fish docks of Hessle Road and the warehouses of Wincolmlee. In 1914, Hull’s population was around 300,000 people, a much larger number than now. North of the ‘Avenues’ was open fields. Spring Bank ended at Walton Street and along Willerby Road was open country side. Along Holderness Road, there was not much housing beyond Portobello Street. The present day housing estates of Bransholme, Orchard Park, Greatfield, Longhill, Bilton and Ings Road were then just farms. Over 80% of the 66,090 homes in Hull were classified as ‘working class’ type, with a rent not exceeding £26 per year. Only 28,400 homes were regarded as satisfactory, with adequate light and air circulation and having a yard or garden at the rear with a secondary means of access. Some 21,800 properties, mostly ‘terrace’ type housing were unsatisfactory, built at a high density of 60 houses per acre, compared with an average of 7 houses to the acre for the City as a whole. They included 2,800 ‘slum houses’ which were old, damp, poorly built and situated in congested districts. Tenants invariably shared a single tap and outside toilets, which were situated together in a communal courtyard. Over 98% of Hull people rented their homes rather than owned them. The homes were largely poor and basic, with little choice, but the rents were cheap. People preferred to live near their place of work and not commute long distances. With no Welfare state and few Council houses, people preferred to live in tightly knit communities, where they could support each other or have access to shops and facilities. For the few and wealthy, home ownership outside the city centre, was the most desired and affordable option. Newspapers in 1914, advertise a 3 bed house for sale in Anlaby Park for £415 – £435, and 4 bed houses for between £529 – £550. After the war, a typical 3 bed, semi-detached house, sold for between £540 – £740.

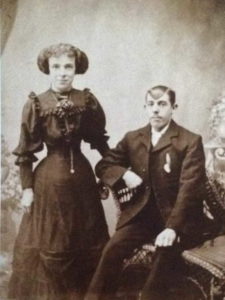

Only 1% of Edwardian’s owned property. Most people worked in dark, noisy factories, cut hay in fields, toiled down dirty and dangerous mines; had bones bent by rickets and lungs racked by tuberculosis. Life expectancy then was 49 years for a man and 53 years for a woman, compared with 79 and 82 years today. They lived in back to back tenements or jerry-built terraces, wore cloth caps or bonnets (rather than boaters, bowlers and toppers) and many had never taken a holiday – beyond a day trip to the seaside – in their entire lives.

The Outbreak of War in Hull

On Tuesday, 4th August 1914, at 11 pm, Great Britain declared war on Germany. It was a gloriously, sunny, Bank Holiday and holiday makers were disappointed that the trains on the North East railway lines had been cancelled for troop transport. The news was greeted by an outbreak of excitement and patriotism. Crowds gathered outside the Hull Daily Mail offices, in Whitefriargate, to hear the news. When Germany refused the ultimatum to withdraw from Belgium, a cheer and patriotic singing broke out. The next day saw hysteria in the shops with panic food buying and hoarding. There was a sudden scarcity of sugar and fruit as the Wilson Line ships were detained in the ports of Hamburg. Prices rose and supplies fell, until order was restored. Hull was full of troops called up and on the move. The Territorial Army was mobilised to defend Britain, while the Regulars were sent to France. The 4th and 5th (Cyclist) Battalions of the East Yorkshire Regiment marched to the coast and dug in, ready for invasion. The Royal Field Artillery from Wenlock Barracks were recalled to Hull from Dundee. Some 300-400 reservists of the regular army left Paragon station for Chatham and other depots. The Posterngate shipping office was busy with Royal Navy Reserve, ‘hard looking, wiry men’, responding to the call, to sign on. Guards were placed on factories and power supplies to prevent sabotage, hospitals were prepared to accept casualties, and appeals for volunteers went out. The docks were full of vessels, as Hull’s 400 fishing trawlers headed for the safety of home. Hull’s Fish Dock was full of a flotilla of ships from the Red Cross and Hellyer’s fleets. Amidst of all this activity, the Government passed the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) on 8th August 1914. This gave it far reaching powers over people. Land and property could be seized for military use, suspected spies could be arrested and imprisoned. Strict censorship of the Press was enforced. In effect, the country was placed under martial law. Tradesman surrendered their horses at the Carr Lane livery stables and motor vehicles were commandeered by army officers in Hull. Sir Mark Sykes, Hull’s Central MP, mobilised 1000 Yorkshire farm wagoners from his estates, which caused a blow to farmers and the local harvest. Father Le Clerc, Chaplain of Endsleigh convent, left Hull to join the 13th French Regiment. Lady Nunburnholme, appealed for volunteers to join First Aid classes and nursing courses, at her VAD, Head Quarters, in Peel Street, Springbank, Hull.

The Belgium Refugees

The German invasion of neutral Belgium and the stories of their atrocities towards the Belgians was a powerful weapon in uniting Britain’s support for the war and in recruitment. On 9th September 1914 Hull established it’s War Refugee Committee to assist refugees until the end of the war. It’s HQ was based at Bowalley Lane and it had 500 volunteer helpers, 400 of which were women. This was a registered war charity that relied entirely on voluntary aid. The committee’s work was twofold. First, to offer hospitality to Belgium residents in their area and secondly to give relief to those disembarking at their ports. This included giving temporary relief with accommodation, food and clothes and for more permanent cases rent free lodgings and allowances for food, clothes and heating. For those who could work, jobs were sought for them. On the whole the refugees were found to be sober, industrious and gracious and many became self supporting during their stay in Britain. The Hull War Refugee Committee for Belgium , in its final report, stated that 1,249 refugees were assisted of which 612 were entertained and 637 were given some temporary material aid. In total, the Committee had received £10, 386 in voluntary subscriptions, donations and collections. This was used to assist and maintain refugees and aid their repatriations.

Support Services

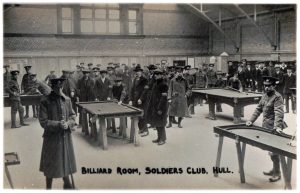

‘Soldiers Clubs’ were raised in Hull to help serving men. A Soldiers Club with reading room was located at Beverley Road baths on Stepney Lane and run by Major A J Atkinson and his wife.

A ‘Soldiers & Sailors Wives Club’ was formed on Mason Street by Mrs Hubert Johnson, the wife of the Lord Mayor. It was devoted to provide relaxation for the wife’s of servicemen away from home.

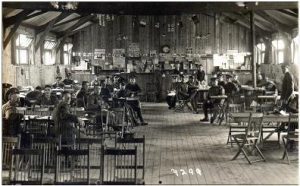

Paragon Railway Station housed a popular ‘Rest Station and canteen’ well used by departing troops. It was set up in September 1914 and staffed throughout the war by Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD).

‘Peel House’ at 150 Spring Bank, was the VAD headquarters, and run by the Lady Mayor. Peel House helped train nurses and locate hospital accommodation for soldiers posted to Hull. It also sent out thousands of parcels of clothing and essentials to troops home and abroad. War Correspondents in France were struck by the way East Yorkshire Units were looked after by people back home. Its most renowned work was sending thousands of food and clothing parcels, plus other necessities to Prisoners of War. This work was extended to captured seaman and interned civilians. Peel House raised public funds to fund their work. The residents of Freehold Street created a bread fund and distributed food to Prisoner of War through Peel House.

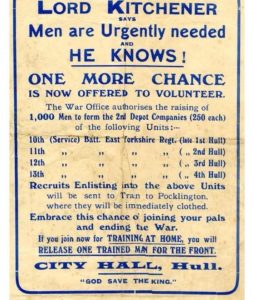

Recruitment

Large numbers of men rushed to enlist in the Army. Recruitment drives were launched, these appealed to men’s patriotism and sense of duty. Local authorities and prominent people took the initiative in recruiting and equipping ‘Pal’ Battalions, confident in the fact that the war office would take them over. This allowed work-mates and friends to serve together and was hugely popular. 30,000 men had joined by the end of August 1914, and 2 million men volunteered by the time conscription came in 1916. In eleven weeks Hull raised enough men to form four infantry battalions (4,000 men in all). The battalions were given unofficial names, reflecting the men’s backgrounds. For example, the 1st Hull Pal Battalion, were known as the ‘Commercials’ because its recruits were from Hull’s commercial and office sector. Other Hull Battalions were made up of local ‘Tradesmen’, ‘Sportsmen’, and Railway workers. The motives for joining were varied – a desire to travel, to escape low paid work, for adventure, but above all a genuine idealism and patriotism. This was the base on which the New Armies and Pal’s battalions were formed. Local papers reported on families at war, that had joined the cause. The ‘Hull and Lincolnshire Times‘, of 29th May 1915, reported on James Fray, of 72 Flinton Street, Hull, with seven family members enlisted, Sergeant, Herbert Thundercliff, wounded at 48 Beeton Street, with ten family members serving and Mr T.G. Marshall, of 96 St Georges Road, with five sons serving and another 15 family members enlisted, including nephews and son in laws.

Large numbers of men rushed to enlist in the Army. Recruitment drives were launched, these appealed to men’s patriotism and sense of duty. Local authorities and prominent people took the initiative in recruiting and equipping ‘Pal’ Battalions, confident in the fact that the war office would take them over. This allowed work-mates and friends to serve together and was hugely popular. 30,000 men had joined by the end of August 1914, and 2 million men volunteered by the time conscription came in 1916. In eleven weeks Hull raised enough men to form four infantry battalions (4,000 men in all). The battalions were given unofficial names, reflecting the men’s backgrounds. For example, the 1st Hull Pal Battalion, were known as the ‘Commercials’ because its recruits were from Hull’s commercial and office sector. Other Hull Battalions were made up of local ‘Tradesmen’, ‘Sportsmen’, and Railway workers. The motives for joining were varied – a desire to travel, to escape low paid work, for adventure, but above all a genuine idealism and patriotism. This was the base on which the New Armies and Pal’s battalions were formed. Local papers reported on families at war, that had joined the cause. The ‘Hull and Lincolnshire Times‘, of 29th May 1915, reported on James Fray, of 72 Flinton Street, Hull, with seven family members enlisted, Sergeant, Herbert Thundercliff, wounded at 48 Beeton Street, with ten family members serving and Mr T.G. Marshall, of 96 St Georges Road, with five sons serving and another 15 family members enlisted, including nephews and son in laws.

However, in 1915, the flow of volunteers was insufficient to meet the army’s needs and public opinion began to turn towards the ‘slackers’ – those men who had not enlisted. In October, Lord Derby, the Director of Recruitment asked all men, aged 18 to 41 to “attest” – to say they that they would join up when called. Men were divided into married and single groups and young, single men would be called up first, before married men. Arm bands were issued to attested men, to spare them the humiliation of being labelled as ‘slackers’. This voluntary recruitment initiative failed to produce the numbers of recruits needed and was replaced with compulsory conscription. On the 5th January 1916, the Military Service Act deemed all single men between 18 and 41 to have enlisted, a second Act in May, extended this to all men between 18 and 41. Finally, with the crises of 1918, a third Act in April, extended the age limit up to 51. However, few of the older conscripts saw action at the Front – rather they formed a home defence force.

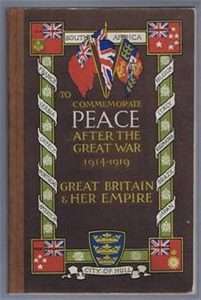

Hull’s contribution during the First World War is often underestimated. As a North Eastern, coastal City with a population of approximately 300,000, over 70,000 men served extensively across all branches of the British Army, Royal Navy, Merchant Navy, Royal Air Force, and the Home Defence. They also died serving Commonwealth nations, such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand where they had emigrated. The outbreak of war in 1914 aroused great enthusiasm in Hull and within the first six months 20,000 local men had enrolled. Hull was also attacked by Zeppelins and it raised its own Pals Battalions. The Great War affected everyone. At home there were wounded soldiers in military hospitals, refugees from Belgium and later on German prisoners of war. There were food and fuel shortages and disruption to schooling. The role of women changed dramatically and they undertook a variety of work undreamed of in peacetime.

Hull formed its own four ‘Pal’ Battalions, the 10th, 11th, 12th & 13th service Battalions of the East Yorkshire Regiment, which made up the 92nd Infantry Brigade, 31st Division. Due to its coastal locality and economic and social make up, Hull formed its own ‘bantam’ regiment made up of men of small stature, with “big hearts”. Hull formed its own heavy artillery and Garrison Brigade to defend the Humber estuary. The 17th Northumberland Fusiliers, a Railway Pal’s Battalion was also formed at King George’s Dock in Hull.

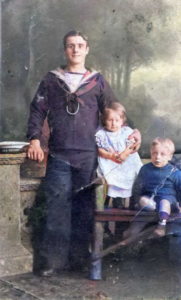

Due to its maritime history, Hull men also served throughout the world, in the Royal Navy, Royal Marines, Royal Naval Reserve, Merchant Service and the Hull Fishing Feet. Hull’s population fell by about 45,000 during the First World War. 75,000 men served in the war effort. Over 7,500 Hull men were killed and over 14,000 were wounded during the First World War. Many of these lived men in the same streets or terraces, which was to make the casualties keenly felt by the local community. The numbers of wounded increased over time, causing considerable hardship for Hull families. The Hull Lord Mayor, Alderman, Hargreaves, reported on 21st February 1919, that 14,000 Hull men had been wounded in the war of which 7,000 had been maimed. Some 12,000 Hull women had also been dealt with by the local Pensions Committee. On 9th September 1924, the Ministry of Pensions recorded that this had increased to 20,000 disabled ex servicemen from Hull and they were dealing with 2,500 Hull widows, 200 motherless and fatherless children and 3,000 Hull mothers and other near dependants. Hull City Council established a Great War, Civic Trust, to assist with the large numbers of widows, wounded and orphans left after the War. This ran until 1963 and raised £165,000.

Thank You to “Hull, the Good Old Days” Facebook, for the above photos.

War Casualties

The war lasted 1,566 days – four years, 3 months and one week. During this time, over 7,500 Hull men were killed. Another 14,000 were wounded, of which 7,000 were maimed and this rose to 20,000 wounded by 1924. On average, there were 15 war deaths received in Hull every day. Neighbouring towns like Beverley also suffered. With a population of 14,000 in 1914, over 3,000 Beverley men enlisted, with 400 killed and another 600 wounded. Cottingham with a pre war population of 3,000, lost 105 men.

These casualties accumulated every day, for four and half long years, increasing as the war went on. More Hull men were lost in 1918 than any of the previous war years. Some days were worse than others. On the the 3rd May 1915, eight Hull Trawlers, were sunk by German submarines. On the 13th November 1916, 247 Hull men died, when the East Yorkshire battalions attacked the village of Serre: Another 139 Hull men died on the 3rd May 1917, when the ‘Hull Pals’ attacked Oppy Wood: 91 Hull men died on the 1st July 1916; the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Another 127 Hull men also died between the 21st and 23rd March 1918, during the great German Offensive. The Hull Daily Mail published many photographs of the fallen and all these are stored on this website to view.

If the authorities knew about the casualties, they did not tell the public, at the time. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see censorship in action. Local Newspapers cleverly under reported grim news and spread out casualties, over time, to conceal the catastrophe. Mounting losses were often reported months after the event, pushed to the back pages, and mixed up with casualties from other towns.. War deaths were often interspersed with patriotic tales, good news stories of recovering wounded and the announcement of gallantry awards. These seemed to lighten the mood and soften the blow. The emphasis was very much on maintaining the war effort and sustaining casualties until the victorious end. Churches were packed, “with hundreds content to stand throughout the service” in Hull’s Holy Trinity Church and “hundreds more unable to gain admission.” (Hull Daily News 5th August 1916). Death tolls never revealed the full horrors and were diluted with deaths beyond the recruiting area. For example, while lists of dead, wounded, and missing often with photographs, appeared in the Hull Daily Mail, the Hull Daily News, and the Eastern Morning News, they hardly compared in length with similar lists in the West Riding Press. The longest single list of East Yorkshires killed on the First Day of the Somme, involved 25 fatalities, mainly from the 7th Battalion, and a mere nine of these were from Hull (eight from Sheffield). The final casualty figures revealed 111 deaths in the 1st East Yorkshires, of whom 49 per cent were born outside the county, and another 29 per cent outside the recruiting area, with only 22 per cent from the East Riding. Of the 34 deaths among the 7th battalion, only 18 per cent came from the recruiting area (all from Hull), with 41 per cent apiece from elsewhere in Yorkshire and from outside the county.

However, news from returning soldiers, the highly visible sight of discharged wounded and the rush of over worked “Telegram Boys”, would constantly remind civilians of the brutality of war. Hull’s four main hospitals and Voluntary Aid Detachment units were constantly busy. Hull was also the main port for repatriated prisoners of war which added to their work load. Hull cemeteries are littered with servicemen that died in Hull far form home. Those with sight impairments were found work at the ‘Blind Institute’ on Beverley Road. Shell shock victims were treated at De La Pole hospital which also had wards for gas wounds. The Brookland’s hospital, on Cottingham Road looked after Officers. The Hull Royal Infirmary dealt with 6,000 war casualties. The Reckitt’s hospital cared for some 3,000 patients during the war. The wounded were very visible in the community. They were often amputees, mutilated, or with appalling facial injuries. Many houses with drawn dark curtains, marked a casualty. It seemed that every family had lost someone, or knew someone that had been killed in the war. Civilians wore dark mourning dress, or black arm bands, to indicate that they were morning the loss of a loved one.

Men physically and mentally broken, or young men who had sacrificed their apprenticeships to go to war, now faced unemployment at home. Rationing of food and basic goods added to the community tension. There were no psychologists or social workers, to treat the victims of shell shock or counsel the large numbers of bereaved. Many families had to cope as best they could.

Newspapers of the time, are full of incidents of violence, drunkenness and anti social behaviour, involving ex servicemen. This reflected the general, poverty, illness and the untreated madness or war casualties. Initial enthusiasm for the war quickly gave way to sadness and shock and a deepening psychological affect on the civilian population. Returning Servicemen had been assured a ‘Land Fit for Heroes’, only to find unemployment, austerity and indifference.

Hull established a number of its own Charities during the war. These included the Hull and East Riding Fund, for the needs of local units and prisoners of war (headquarters at Peel House, Peel Street, Hull); Hull Social Club for Soldier’s and Sailor Wives, Mason Street, Hull; The Lord Mayor’s Local War Relief Fund; Hull District War Refugees (Belgian refugees); Interned Hull Seaman’s War Charities (to provide necessities and comforts for merchant seaman, interned in enemy territory); Hull Patriotic Fund for widows of soldiers and sailors, and the Hull Great War Civic Trust in 1918t help Hull’s wounded and their Dependents; Hull Bread Fund to supply English Prisoners of War: The Hull & Barnsley War District Relief Fund, to assist dependents of their railway staff serving.

Every aspect of home life was affected by the war. The ‘Hull Times‘, showed how Hull’s 2,128 allotments, (over 280 acres), were cultivated for food production. The railways and trams were given priority for war business. Buildings were taken over for recruiting, for wounded, ‘soldiers’ rest places and even ‘social clubs’.

The Soldiers Club based at Beverley Road baths had a library, weekly concerts, a rifle range, a reading room, writing facilities and refreshment bars. So popular and well known was the club that soldiers wrote about it in newspapers all over the country.

Hull Residents set up a number of funds to help the war effort. Among these was the ‘Christmas Pudding Fund‘ for local soldiers, that helped raise 5,000 shillings, helping to feed 10,000 Hull men. Another, was a national fund, to help East Yorkshire soldiers, serving on the Somme. It received donations from across Britain and raised £250 to help the men at the front. Hull theatres helped the war effort by providing entertainment. One such show was named “The King visits his troops on the Somme Front”. It was an officially made short, from the War Office, and showed at various theatres, including the Theatre De Luxe. Other theatres, such as Sherburn Theatre, in Sherburn Street, east Hull, showed “The Battle of the Somme”, a five-part movie, featuring graphic war images from the front line.

The war, took thousands of young men away from home. Many were were exposed, for the first time, to new vices, such as alcohol, tobacco, violence and prostitution. They would return home with bad habits, swear words and bawdy songs. The war had trained them to survive, take risks and show initiative and for some this would lead to new careers in organised crime. Church attendance also began to fall as people struggled to reconcile their losses with their faith. New religions, such as ‘Spiritualism’, became popular as people tried new ways to reconnect with the dead. Citizens also wanted to travel abroad to visit the battlefields and cemeteries. Travel companies, like Thomas Cooks, emerged to offer organised tours of battlefields for civilians, for the first time.

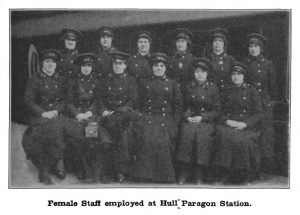

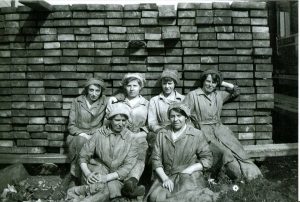

The war opened up many different opportunities for women as men left the town for the front. Servants left middle class houses and received a regular wage for the first time. Women worked in munitions and on the land, or became post women and police officers. The war years saw 1,600,000 women employed by the Government nationally, on public transport, in the Post Office, in commercial offices, working on the land and in factories. The Women’s Land Army was sawing timber, looking after calves, baling fodder, but not carrying corn. Eventually over 260,000 women were working on the land. This number dwarfed the 87,000 who served in the Land Army in the Second World War. In 1918 women were urged to quit home for the factory and sign up at the local Labour Exchange. The War Work of many women was nationally recognised, such as Jennie Hopperton of Beverley, a VAD with St. Johns Ambulance Association, who was brought to the notice of the Secretary of State for valuable services rendered in connection with the War. The Belgian King awarded the Medaille de la Reine Elizabeth to Mrs Kirby of St. Mary’s Vicarage for her work with Belgian refugees and soldiers. The Military Medal was awarded to Miss Constance Todd for devotion to duty and presence of mind during an enemy raid.

Language

The First World War also introduced new words and phrases into the language. Some of these words included, “camouflage, pill box, tank, plonk, bumf, guff (rumours), dud (a failure), demob, conchie (conscientious objector), and streetcar (a name for a shell)”. “Snapshot”, “bloke”, “scrounge”, “washed up”, “binge drink”, “trench coat” and “duckboards” were other trench vocabulary, brought home. “Skive” came from the French word ‘esquiver’ (“to escape, avoid”). “Bully” Beef came from the French word boulili, meaning boiled. “Strafe” meaning to ‘punish’ in German, was also adopted. “Swipe” was a Canadian word, “Cushy” was a Hindi word meaning pleasure. Backchat – pronounced as batchit, came from a Hindi word meaning conversation. “Dingbat” was an Australian word that referred to an Officer’s batman or an irrational individual. “Lousy” and “crummy” both referred to being infested with lice, while “fed up” emerged as a widespread expression of weariness among the men. Other trench slag included “Cop It”; “Cubbyhole”, “Doolalley”, “Having a field day”; “Muck in”, “Muck about”; “Spit and Polish”; “swinging the lead”. Other words included “Zero Hour”, “Over the Top”; “Jam on it” also entered the common language. “Goodnight kiss” was the term used for the last shot made by a sniper at the end of an assault.

“Shell shock” and “Trench foot“ became new medical conditions. “Conked out”, and “blind spot” came from air force expressions. Several phrases from the criminal underworld also entered wider use, among them “Chum” – formerly slang for an accomplice – “rumbled” (to be found out) and “knocked off” (stolen). Soldier phrases, like, “Having a chat“, (sitting around de licing clothing), ‘copped a packet’ (wounded or killed), ‘pushing up daisies’ (an euphemism for death). “Argue the Toss” derived from a trench gambling game involving flipping a coin. “A Fair Whack” (sharing parcels) and ‘Over the Top’ are still terms, widely used today. ‘Zepps in the Cloud’ became a popular term to describe sausage and mash, but is less used now.

Fashion, hair styles, clothing, and cosmetics, also changed with the war. Tight corsets and bodices were replaced with more free flowing clothing. Women wore shorter hair and skirts, and sometime wore trousers to be practical. They wore lipstick and courted sun tans to display affluence. The phrase a ‘Girls night out‘ was first coined during the war, to describe female munition workers, spending their wages together, unchaperoned around town.

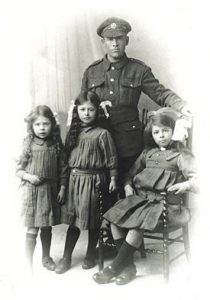

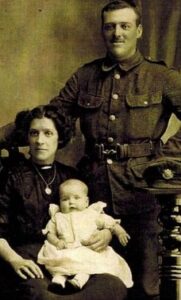

13th EYR, with wife Edith and son, at 3 Argyle Street, Hull. He died on 10/07/1916,aged 29.

Member of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in her uniform. (c) Hull Museums.

Demographically, Hull’s population fell by 45,000 people during the war, such was the rate of male enlistment into the armed services. Women replaced many men in the workplace, and in Hull, women found new jobs in the Post Office, railways, trams and factories. The Hull Daily Mail ran articles on women’s war work, saying “they were being trained in ship building, the dock yard, transport and munitions,” as well as growing food, postal work, telegraph messengers and even taxi driving. The National Union of Women Workers, organised voluntary patrols in Hull, acting as a ‘morality’ police force, curbing crime and prostitution. ‘Joseph Rank Ltd’, employed nearly 3,000 women, in wheat production. ‘Rose Downs and Thompson’ Munition’s factories, employed 359 women, 13 under 18 years of age and 341 between 18 and 51 years old. Many local businesses were badly affected by the loss of manpower. Some used women or injured ex-servicemen in place of the men they had lost, while others had to reduce their opening hours because of staff shortages. Women were paid only half the wage of equivalent male workers. Irish labourers got 50/- per week for helping with the harvest. The ‘Women on the Land’ Committee reported that women between 18 and 40 got 15/- per week during their 3 weeks training, then 18/- per week once trained, plus a free uniform. Munitionettes received 32/- a week.

Madam Clapham’s, dress making salon at Hull’s Kingston Theatre Hotel, employed another 150 women. They redesigned women’s clothing to make war fashion more comfortable, modern and easier to wear. Emily Clapham’s gained a thorough training in the dressmaking trade. She had a good eye for fashion and colour and combined this with good business sense. She went into business with her husband Haigh Clapham in 1887 and invested their savings to purchase No.1 Kingston Square, Hull. Her reputation as a fine dressmaker was at its height from 1890 until the outbreak of the First World War. This was an era of strict dress codes and dressing for many social engagements, like race meetings, balls and dinner parties. In the 1890’s the salon was so successful that Madame Clapham purchased number two Kingston square in 1891. Number three Kingston Square was purchased just before the First World War, with a legacy left to Madame Clapham by her aunt.

Madame Clapham died aged ninety-six on the 10th January 1952. Emily Wall, Madame Clapham’s niece and employee continued Madame Clapham’s legacy at number 3 Kingston Square under her aunt’s name until 1967. Madame Emily As Madame Clapham’s reputation grew she received many orders for dresses for clients, to be presented at court, wearing during the “coming out” season. Madame Clapham added the title of Court dressmaker to her Salon’s labels in 1901 as a mark of her highly regarded reputation. The First World War had a big impact on Madame Clapham’s business as it resulted in a decline for the exquisite dresses of the earlier years. Attitudes and Social codes changed after the war and women gained a greater degree of freedom. Madame Clapham still created evening dresses in the new styles and expanded into corsetry and under garments to fit under certain dresses. Madam Clapham is pictured above.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p02b1136

Women entered the armed forces in 1917, in non combatant roles, so releasing men to fight. Many women also became V.A.D.’s (Voluntary Aid Detachments), working as nurses. In Hull, ‘Reckitt’s’ had their own hospital with 45 beds, and there was also a Naval hospital at Argyle Street, with room for 220 patients. The Report of the ‘East Yorkshire Women’s Agricultural Committees’, showed that 600-700 women registered for land work. In total, 928 Hull women did some type of work on farms, allotments or market gardens. Male labour was not scarce and there was a strong prejudice against women.

Children – It is well known, that many young people lied about their age, to enlist in the war. It is perhaps less well known, that nearly 1,200 Hull teenagers, died in action during the First World War. Searching by age, on this data base, shows that Hull’s war casualties, included, three, 14 year old’s; sixteen, 15 year old’s; forty two, 16 year old’s; eighty two, 17 year old’s; three hundred and forty, 18 year old’s; and six hundred and ninety, 19 year old’s. Children also played an active part in the war effort at home. Boy Scouts, guarded telephone and telegraph lines, railway stations, water reservoirs or any location that might be militarily important. From late 1917, many Scouts assisted with air raid duties, including sounding the all-clear signal after an attack . Girl Guides packaged up clothing to send to British soldiers at the front, prepared hostels and first-aid dressing stations for use by those injured in air raids or accidents, tended allotments to help cope with food shortages, and provided assistance at hospitals, government offices and munitions factories. Sea Scouts were part of a network of observers, that stood watch on the coast, in anticipation of German air attacks or a possible invasion. Children across Britain gave their pocket money to the war effort. The children raised money for a number of charities, including St Dunstan’s Hostel for blinded ex-servicemen, the Blue Cross for sick and injured animals, and local military hospitals. Children also collected scrap metal and other essential materials that could be recycled, or used for the war effort. Children younger than the school leaving age of 12, also worked in factories or on farms. In some cases, a child’s earnings could be a helpful addition to a family’s income. In 1917, Education Minister H A L Fisher claimed that as many as 600,000 children had been ‘prematurely’ put to work.

Air Raids and Trawler losses.

Beverley’s Westwood was quickly requisitioned for an aerodrome in 1914, when Military Authorities requisitioned 179 acres of Westwood, including the race course and part of the Hurn, for an aerodrome. The main road to York was closed and sentries placed at the junction with Newbald Road and at Killingwoldgraves to inspect the passes of people working in Beverley. Its location was not without its problems. A total of 17 airmen were killed in flying accidents while serving at RFC Beverley, their names are commemorated in a plaque at Bishop Burton Church. The 13th Hull Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment was also encamped on Westwood for a while. In June 1917 one of the aeroplane sheds was used as a new Aeroplane Repair Section. By April 1918 there were 332 staff on the site including 18 officers, 40 officers under instruction and 128 rank and file. There were

Beverley’s Westwood was quickly requisitioned for an aerodrome in 1914, when Military Authorities requisitioned 179 acres of Westwood, including the race course and part of the Hurn, for an aerodrome. The main road to York was closed and sentries placed at the junction with Newbald Road and at Killingwoldgraves to inspect the passes of people working in Beverley. Its location was not without its problems. A total of 17 airmen were killed in flying accidents while serving at RFC Beverley, their names are commemorated in a plaque at Bishop Burton Church. The 13th Hull Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment was also encamped on Westwood for a while. In June 1917 one of the aeroplane sheds was used as a new Aeroplane Repair Section. By April 1918 there were 332 staff on the site including 18 officers, 40 officers under instruction and 128 rank and file. There were

24 aircraft. It was necessary to train pilots and observers in Canada and Canadian squadrons passed through Beverley on short stays.

On the 3rd May 1915, Hull mourned the loss of eight trawlers on one day. On the 6th June 1915, Hull civilians, experienced the first of eight bombing raids by Zeppelins. The next day Anti German riots broke out throughout Hull, and many German owned, businesses, were damaged. Hull was the scene of one of the most moving funeral possessions of the war, when the victims of the E13 disaster were brought ashore. The E13 submarine had left England on 15th August 1915, for deployment in the Baltic. On 18th August it ran aground in the neutral, narrow waters between Denmark and Sweden, whilst sailing on the surface. A German destroyer opened fire on her, badly damaging her before being stopped by Danish motor boats. Whilst transferring survivors to Danish ships, the Germans continued to torpedo the submarine which blew up. Fifteen men died in the incident, which caused world wide outrage, as it occurred in neutral Danish waters. (Denmark later gained an official apology from Germany). The bodies arrived in Hull, for transport to their home towns, on 27th August 1915. The next day, a funeral procession for the E13 victims, passed through a packed Victoria Square, en route for Paragon Station. Of the dead, one was a local man, Herbert Staples, an engine room artificer. His body was taken home to Grimsby by tug.

The Zeppelin’s route to Hull was anything but direct. Because of fog, it had already abandoned its initial mission to reach London. It then flew over Norfolk and started its final run on Hull after making landfall near Bridlington.

19:25 – The first warning of a possible pair of Zeppelins came from intercepted wireless traffic. The crafts were somewhere out in the North Sea.

21:30 – Major General Ferrier, commander of Humber defences, ordered all lights in Hull extinguished.

22:20 – Airship seen at Flamborough head

22:30 – Seen at Hornsea

22:40 – Seen at Withernsea

23:00 – Over West Ella, moving eastwards towards the city following the railway lines then veered towards the Humber estuary.

23:45 – L-9 was spotted above Hedon.

Cinemas, Halls and Picture shows The ‘Tower’ Cinema, opened in June 1914, on Anlaby Road, as a a Picture Palace to entertain audiences in World War One. It was one of 30 cinemas in Hull. Viewers walked into a venue, holding 1,200 seats, across stalls and a single balcony with a cafe, that overlooked the street outside. The Tower showed the latest silent movies, provided news in Europe, and. It also presented patriotic films, produced to raise money for the local war Trust. During WW1, the Tower played a host of patriotic films including ‘The Heroine of Mons’ and even a live concert in 1915. Cinema not only changed the Hull’s perception of war, but turned the experience of going to the cinema into a desirable, class-free commodity that is still much loved today.

Hull’s Royal Visit

On the 13th June 1917, King George V and his wife Queen Mary, visited Hull, driving through the City in an open carriage. Huge crowds came out to see them and Hull was decorated with flags, bunting and streamers. The Royal visit took in a number of sites including Earle’s shipyard, the Holmes engineering works, the VAD hospital on Cottingham Road and the naval hospital on Argyle Street. They also went to Hull City football ground and met members of the Volunteer Forces.

Video of the Kings Visit to Hull – http://www.britishpathe.com/video/king-george-v-visit-to-hull/query/Hull

Prices, Tax and Food Rationing

In Hull, income tax increased as did the number of people paying it. Whilst wages improved, many goods were more expensive and became un-affordable. Income tax increased five times between 1914-1918 and was paid by twice as many people. It would never fall to pre-war levels again. During the war, prices increased on all the basics: rent, fuel and clothing, as well as food. However, food prices increased most sharply and continuously throughout the war, sometimes at an alarming rate. Food prices overall rose by 60%, sugar, eggs and meat prices increased by 400%. By 1917, bitter beer was 5 times the price it was in 1914. In 1918 there was a further increase in the duty on spirits, beer duty was doubled. As beer became scarce, publicans stopped serving pints; landlords were selling beer by the glass which equalled a third of a pint. ‘Government’ beer was not popular. Many farmers in Hull and East Riding produced their own beer for their workers.

Food became a growing concern for people, not just the quantity, but the quality. There were no fridges or freezers to preserve food, all food was perishable, and therefore had to be brought fresh and daily. Food became increasingly scarce due to enemy attacks on shipping and a poor weather in 1916, which ruined cereal and potato harvests. Potato’s were replaced by less nutritious turnips. These shortages provoked frustration, food queues and hoarding. Parliament announced in 1916 that there were only six weeks of food left in the country. The Government limited the number of food courses that could be served at meals in restaurants and hotels. In 1917 the harvests also failed in France and Italy. Considerable supplies of food also had to be diverted to those countries. This reduced the quality of bread in Britain. No one liked ‘War Bread’ which was said to cause “rashes, indigestion, dysentery and lowering of body strength”, and an investigation was ordered. The price of flour had soared. There was a prohibition on baking ‘light pastries’ but cakes, buns, scones and biscuits were permitted providing they had only 15% sugar. It was noted with envy that in Hull people could still buy cheesecakes, lemon and jam tarts, but not in Beverley. A bacon famine was feared because of the cost of feeding pigs, and an outbreak of swine fever meant lots of healthy pigs were slaughtered. However, by the summer of 1918 bacon and ham were released from rationing. Horses were requisitioned to pull artillery, ambulances and supply wagons. In the first few weeks of the war 170,000 horses had been supplied to help the war effort. Prices dropped drastically. A horse sold pre-war for £2,000, in 1915 resold for £105. The loss of thoroughbred horses caused concern about the future of horse breeding as over 250,000 horses had been killed by May 1917.

To prevent Britain being starved into submission, the Government built more merchant ships, developed the convoy system, set up the Women’s Land Army and introduced allotments, to help increase food production. 250,000 land girls, 84,000 wounded soldiers, 5,000 schoolboys and 30,000 prisoners of war, were put to use on the land. Although, 2,240 steam tractors ploughed up an extra 1.2 million acres, in 1917, they only increased the Britain food surplus to last for one more month. In January 1918, Britain introduced food rationing.

Many of today’s allotments were originally established during the First World War. The East Riding War Agricultural Committee was created to increase food production. Beverley got its first allotments in 1914 amid fears that food stocks would not get the nation through to the next harvest. The local papers always had information on how to grow food, agricultural notes, Home Hints & Garden Gossip. Courses on War Time Gardening were provided for nine Beverley teachers who would then train school children. By 1917 there were 41 acres of allotments in Beverley; Kitchen Lane, Captain Samman’s field, Morton Lane, Scarr’s Field, the Football field, Wellington Terrace, Norwood, Grovehill Road, Holme Church Lane corner. The following year the committee identified about 20 acres available for 300 more allotments in Pasture Terrace, Kitchen Lane, Cattle Market Lane (2 ½ acres), and Queensgate. A further 20 acres of Figham and 3 or 4 acres of Westwood on the Fishwick Mill site could be ploughed and cultivated. Allotment holders had their problems. They were accused of undercutting Market Gardeners and criticised for working on Good Friday, but protested they were doing “the best piece of good work possible”. The use of cooked rhubarb leaves instead of cabbage almost killed a woman. Gardens were invaded by rooks and pigeons, commonly believed to be fleeing the fighting in Europe. The East Riding War Agricultural Committee organised shoots to provide “good human food”. A letter in the Beverley Recorder suggested only shooting the foreign birds and not the native pigeons! There were problems with children ‘scrumping’ apples and one man complained about losing a third of his shallots to thieves.

In 1917, the East Riding War Agricultural Committee, decided that 70,000 acres of grassland should be ploughed up, which would require 450 tractors. Farmers were unhappy about ploughing land which could feed cattle or sheep, but was largely unsuitable for corn. In 1918, the Cultivation of Lands Order said that not less than 60% of arable land should be sown with the following crops for Harvest 1919 – wheat, barley, oats, rye, flax, potatoes or carrots. By mid 1918 the area under corn and potatoes in the East Riding increased by 90,000 acres and a good harvest was expected. Soldiers, women, and 40 German POWs billeted in camps would get in the harvest. Horse racing had been stopped on the Westwood. Foxhunting was prohibited and hounds would be sent to the USA and returned after the war in the belief that tons of crops would be saved and men released for the forces. 50% of hounds were destroyed.

Despite appeals for people to cut down on food, potatoes, sugar, butter and margarine were in great demand and very scarce. Food rationing was introduced for the first time, in Britain, in February 1918. This started with sugar, and then restrictions on meat, butter, jam, and margarine. Cheese and tea were rationed locally. Ration coupons were issued to control rising food prices and share out limited food supplies fairly. Ration cards were issued and people registered with a local butcher or grocer. The weekly ration was set at 15 ounces of meat, five ounces of bacon and four ounces of butter or margarine. With rationing, food queues disappeared and everyone received a fair share. Prices kept high, but the threat of shortages was averted. Grocers were liable to be imprisoned if they imposed conditions on the sale of sugar, such as a requirement for other things to be bought at the same time. A greengrocer was fined 10/- for refusing to sell potatoes to people who weren’t his regular customers. Beverley tobacconists did good business before Christmas because of people sending cigarettes to the lads at the front. Tobacco went up from 6/5d to 8/2d per pound, a rise of 2d per ounce to the consumer. Matches went up from ½d to 1d. There was an increase of 2d in the shilling on luxuries. In February 1918 Free Demonstrations of Economic Cookery were held. The withdrawal of labour from food production and the difficulty of importing goods safely created tremendous food shortages. People were told to drink coffee instead of tea. Beverley Grocer, Richard Care, advised, “Drink less tea, use Care’s coffees and cocoa”, while Abrams’ shop sold “Coffee for Tea Drinkers. While tea is short we strongly advise the people of Beverley & District to Drink Abrams’ Coffee. Put plenty in and Make it Good. Don’t forget that pinch of salt”. Coal shortages meant everyone must conserve gas and electricity. Paper was in short supply so experiments to combine 25% of waste paper with sawdust, straw, oat husks, or potato stalks were all tried with varying results. Remnants of candle wax were used as floor polish. Fine ashes mixed with vinegar made a splendid metal polish. Restaurants and cafes could not serve meals between 9.30 p.m. and 5.30 a.m., potatoes could only be served on Fridays and meat was off the menu on two days a week so vegetarian sausages were introduced. No gas or electricity should be used in places of entertainment between 10.30pm and 1pm, the following day. Shops had to close early in 1918 to conserve coal and gas stocks.

The Government set up 363 ‘National Kitchens’, including one in Hull, to feed people during World War One. The Hull Kitchen, opened at Porter Street, Hull, on Friday 28th June 1918. It served teas, from 8.30am to 9.30pm, with dinners, between 11.30am to 2pm and hot suppers, between 7.30pm to 9.30pm. Its speciality dish was beef sausages, served with potatoes and peas, for 6d (about £1). These kitchens improved diets, cut down food waste and proved hugely popular. A bowl of soup, a joint of meat and a portion of side vegetables cost 6d – just over £1 in today’s money. Puddings, scones and cakes could be bought for as little as 1d (about 18p). These self-service restaurants, run by local workers and partly funded by government grants, offered simple meals at subsidised prices. A 1918 ‘Scarborough Post’ story about the national kitchen in Hull, emphasised the ambition of the typical urban outlet: “The place has the appearance of being a prosperous confectionery and cafe business. The business done is enormous.”

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-33275833

Spanish Flu

On 29th May 1918, the Hull Daily Mail reported that a type of influenza was sweeping through Spain. The ‘Spanish plague’ was causing many deaths and the Government offices in the country had closed. Many businesses were also forced to shut their doors and two thirds of the tramway staff were off work ill. The Hull Daily Mail reported on 28th June, 1918 the strange flu had hit officially hit Hull. The lengthy article reported a policeman was found at laid out on the floor of the middle of Woodcock Street and had collapsed as a result of the “Spanish Flu.”

The first recorded victim was an Indian seaman who

had sailed into Hull and died on board his vessel once it was docked. Official death records show that he was a 25 year old with the surname of Nomezulla.

Dr Riley, director of education in Hull, reported no unusual absences in Hull schools due to the virus, but one Hull doctor revealed over 100 cases a day were passing through his surgery, with at least 20 serious cases visited at home. He added that “a few fine days and it should be all cleared away.”

The reality of the situation struck home when children started dying. On July 1st 1918, it was reported Kate Denman, an 11 year old of Hodgson Street, had passed away of the condition. An inquest heard her lungs were in a state of inflammation and that the cause of death was pneumonia caused by influenza. The second case reported was of Elsie Barton who was the 9 year old daughter of a soldier who died under similar circumstances at her home in Arthur’s Terrace, off Courtney Street.

Death tolls

At the end of 1918 the total death toll, according to the Annual Health Report from the Hull Medical Officer, was 975. The worst affected area was South Newington, with 122 deaths reported, and the worst age group affected was those between 25 years old and 45 years old, with 280 people dying in the city in that age bracket.

Waves of the virus

The official medical report stated Hull suffered three outbreaks between 1918-1919, with the first wave hitting Hull in June and July 1918, the second wave hitting in October, November and December 1918, and the third wave arriving in February, March and April 1919. It stated that it did not matter what social class or what district you lived in, everyone was at risk.

The first wave claimed the lives of 78 people, the second wave 872 deaths, with the third wave claiming 265 lives.

The authorities decided it was pointless closing schools, they felt the disease was so widespread among the population it was a pointless exercise.

Dr Wright Mason, the Medical Officer of Health for Hull advised that anyone with symptoms should self isolate in bed and keep warm. He warned meeting with other people was dangerous and aided the spread of the disease, and that this led to unnecessary risks, and secondary complications. He insisted efforts had been undertaken in Hull to stop the spread and Hull Corporation Sanitary Authority were hard at work, but the disinfection of houses was not required. He advised all people needed to do at home was to keep rooms ventilated and keep fresh air flowing through the room, with the patients who were suffering to be kept wrapped up warm and out of draughts.

One of the strangest twists came on July 12, 1918, when a letter writer to The Hull Daily Mail advised the best way to combat influenza was to eat raw onions. The writer revealed he had been an eater of raw onions for years and had never had influenza.

Second wave – October to December 1918

On October 10, 1918 another wave of influenza had arrived, and was hitting hard in many provincial centres. A large outbreak was reported in north-west Hull. Dr Wright Mason said that any children showing early symptoms should be kept from school and the head teachers immediately notified. It was also reported that a clerk in the employ of the Hull Corporation had suffered two deaths in his family, when his children, aged six and two, had died as a result of the influenza.

On the 9th November, 1918, it was reported that residents of Hull might have to wear masks in a bid to stop the spread. The American Army had invented a mask that was proving to be successful and delivering a high degree of immunity. The mask would be worn over the mouth and nose and was made from impregnated gauze. Very few people took up the mask wearing at the time and at least one person was pulled before the police courts for refusal to wear a mask in a public place.

An order was made by the Government that from 25th November,, 1918: “No entertainment shall be carried on for more than three hours consecutively. “There shall be an interval of not less than thirty minutes between any two entertainments. “During the interval the place shall be effectually and thoroughly ventilated. The rules applied to cinemas, theatres, music halls, pubs, clubs and other venues.”

Third wave – February to April 1919

On the 15th February, 1919, the disease was once again spreading in the north and was present in Hull. Dr GW Lilley told warned there were signs of an increase in cases. He said there was no need to worry and that cases were predominantly among the aged. The Hull Medical Officer for Health in Hull reported there had been 12 deaths in Hull in the previous week, compared to the 9 cases the week before.

Every Friday reports were published showing the weekly death figures but, while the third wave was prominent in Hull, figures began to drop and death tolls decreased. By the end of the outbreak, the total number of deaths in Hull from Influenza was 1,261. “Spanish Flu” ended up killing around 50 million people worldwide, which left a death toll three times higher than those killed during the First World War.

Armistice, Peace & Hull Street Parties.

Hull Citizens celebrated the end on the war on the 11th November 1918. The final ‘Hull Pals’ returned to the City on the 26th May 1919. Official ‘Street Parties’ were held across Hull on the 19th July 1919 to mark the official Peace. There were wild celebrations and relief that over four years of struggle were finally over. With this relief, there was also sorrow at the large loss of live. Hull alone had lost over 7,500 men in the war, with another 14,000 disabled from an estimeated 70,000, who had served in the forces. To aid the disabled and the families of the dead, Hull established it’s own War Trust to raise money and by 1927, 1,040 recipients had received £74,000 between them. The war had affected everyone in some way, and the life for many could never be the same again.

Scarborough Street Peace Party to celebrate the WW1 Armistice

Scarborough Street Peace Party to celebrate the WW1 Armistice