The First World War was an artillery war. The Royal Artillery like their motto “Ubique” served everywhere and suffered nearly 50,000 casualties in the First World war. The Regiment used an immense range of weapons and has its own unique War Memorial at Hyde Park Corner in London.

The Heavy Guns of the Royal Garrison Artillery, fired large calibre, high explosive shells, in fairly flat trajectory fire. Britain defined the size of artillery by the weight of the shell. In 1914, the heaviest artillery gun was the 60-pounder, with four guns to each heavy battery. However, some had obsolescent 5 inch howitzers. As British artillery tactics developed, the Heavy Batteries were mostly employed in destroying or neutralising the enemy artillery, as well as putting destructive fire down on strongpoints, store dumps, roads and railways, behind enemy lines.

Artillery caused 60% of all war casualties and 75% of Trench injuries. It was the most devastating weaponry of the war, and won battles.

Despite the long Royal Navy tradition of using heavy artillery, the British Army had little heavy field artillery before World War I. This caused a serious disadvantage for the British infantry in the first years of the war.

In 1914, Britain’s artillery, consisted of the Royal Horse Artillery, (light, mobile, 13 Pounder guns, to support the cavalry), the Royal Field Artillery, (more numerous, medium sized, 18 Pounders, to support front line infantry) and the Royal Garrison Artillery, (using heavier, 60 Pounder guns, to break defences). It also drew experienced gunners, from Britain’s coastal defences, local territorial forces, like the Honourable Artillery Company, and the Royal Navy’s, Royal Marine Artillery, which used Heavy Howitzers. Britain had a highly professional artillery force in 1914, but small compared to Germany, Austria and Italy and insufficient to break the deadlock on the Western Front.

There was a serious shortage of shells in 1915 and through necessity, Britain developed a war economy, to mass produce munitions, and armaments. This enabled Britain’s Artillery to build bigger guns, with better shells and fuses, that could dispense chemical weapons and fire high explosive shells, higher, further and faster. There were four types of shell used – direct action, delayed action, shrapnel and poison shells, each case painted a different colour, to distinguish in the heat of battle. The Shells were heavy and often had to be hauled by animals. Even with the inventions of new technologies like aircraft, machine guns, and tanks, artillery remained the primary weapon on land during World War I. Artillery was the principal threat to ground troops in the war and was the main reason for the development of trench warfare. Britain alone produced nearly four million rifles, a quarter of a million machine guns, 52,000 aeroplanes, 25,000 artillery pieces and over 170 million rounds of artillery shells by the end of the war.

On the Western Front, Britain created new types of artillery, like Mortars, to support trench warfare and larger Siege Howitzers, to destroy strongholds.

Larger, modern recoil artillery, were manufactured, like the British 12-inch (Mark III) Railway Howitzer, that was 41 feet long, weighed 76 tons and fired a shell a minute, over 13,000 meters.

The British 4.5-inch howitzer, which fired four rounds a minute, over 7000 yards, soon became the standard British Empire howitzer, firing in an upwards, curved trajectory, over hills. The 182 available at the outset of the war became 3,177 more over the next four years.

The British 60-pounder field gun, used mainly for counter-battery, required 8-12 horses to transport it and fired 2 rounds a minute, over 10,000 yards. The British 9.2-inch (Mark I) Howitzer became the principal counter-battery weapon, firing 2 rounds a minute, over 10,000 yards. The gun initially served only on the Western Front with 36 British, one Australian and two Canadian batteries, but was soon expanded. Old heavy guns also remained in use until the end of the war and after.

During the war, the artillery grew not only in terms of absolute numbers, but as a relative share of the entire army. Between 1914 and 1918, the Royal Field Artillery had increased from 45 field brigades to 173 field brigades, while the heavy and siege artillery of the RGA had increased from 32 heavy and six siege batteries, to 117 heavy and 401 siege batteries. With this increase came the need to find a more efficient method of moving the heavier guns around. Tractors were used for the first time and large Naval guns were mounted on various railway platforms to offer long range support.

Guns were used for a range of vital work both offensively and defensively. Operating an artillery piece was a complicated, technical process, carried out by teams of men, working in confined gun pits. The work of the gun crews was physical and dangerous. Gun emplacements were dug by hand, in all weathers. Gunners had to lay stable, timber platforms and sandbagged guns for protection. The guns were heavy and cumbersome, 8-inch howitzer shells weighed 200 pounds and crews were expected to fire 800-1000 shells a day during heavy bombardments, all the time, being observed, shelled by enemy and surrounded by live ammunition.

Command and control of the guns was improved throughout the war. Divisional Batteries spread across the battle, became Heavy Artillery Groups after February 1915, and in 1916, these were commanded by Army Corps, which meant guns could be physically moved, to where concentrated fire was most needed.

The artillery became more mechanised, replacing horses with motorised transport and railways. Observation and Signal units, were improved to spot targets. Lieutenant William Lawrence Bragg developed “Audio ranging” to determine the location of targets by means of acoustics. Later “Light Spotting” would be developed to locate enemy guns by their gun flashes.

Telephones, Radio and Wireless would be used for the first time, to improve artillery communications. These would be linked to the new Royal Flying Corps, to provide better aerial observation and co-ordinated artillery fire. Artillery tactics also changed, using “Box barrages” to concentrate fire, on specific areas, “boxed” on a map, and the “creeping barrage” to destroy obstacles in the path of advancing infantry. Guns became more accurate, allowing precision artillery fire, in surprise attacks. Britain rapidly developed a strong, powerful artillery, that was destructive and feared. For example, British guns supported the American offensive, in 1918 and were highly praised by the Americans for their flexibility and effectiveness. It was realised that the important effect of the barrage was to demoralise and suppress the enemy, rather than physical destruction; a short, intense bombardment immediately followed by an infantry assault was more effective than the weeks of grinding bombardment used in 1916. British artillery rained down high-explosive shells, shrapnel and poison gas on the enemy. Heavy fire destroyed troop concentrations, wire and fortified positions. By the end of the war, the enemy were no longer safe and could be constantly fired upon. British artillery could neutralise German guns, almost as soon as they fired. Artillery in short, had become a war-winner.

The 1st Hull Heavy Artillery

With the shortage of Heavy artillery, Hull had the foresight to recruit it’s own Heavy Artillery and Support Column, when war began. A typical Heavy Battery, contained 5 Officers, 170 men, 4 artillery pieces, 8 ammunition wagons, 86 draught horses and between 17-26 riding horses. Hull recruited :-

– the 11th RGA (1st Hull ) Heavy Battery, formed on 1st May 1915. It trained with the 11th Division and became known as the 11th RGA. This went to East Africa, on the 8th February 1916 and later went to France in 1918; Recruited in Hull, it was the first unit of the Royal Garrison Artillery raised for the new ‘Kitchener’s Army‘.

– the 124th RGA (2nd Hull) Heavy Battery, formed in Hull June 1915, proceeded to France, in April 1916 and served there, until the end of the war;

– the 146th RGA (3rd Hull) Heavy Battery, formed in Hull, on 22nd May 1916 and served in France from June 1916, onwards.

– the 32nd (Hull) Divisional Ammunition Column, RFA, was formed in Hull, in September 1914, from local Policemen and Tramway workers. Commanded by Lt Col, James Walker. It became the 38th (Hull) Divisional Ammunition Column, on 14th May, 1915, joining the 31st Division on 8th December 1915. It embarked from Southampton, on 29th December 1915 , disembarked at Havre and joined the 32nd Division, at Argoeuves the next day.

As artillery expanded and evolved during the war, Hull also formed new artillery support units, such as the:-

-

32nd (Hull) Heavy Trench Mortar Battery (formed in April 1916 from the Divisional Ammunition Column, was later re-designated to V.32; and became X.32 Medium Battery, on 12 February 1918.)

The Hull Heavy Batteries saw many changes during the the war. They served with numerous Divisions, under different Heavy Artillery Group and different Army Corps Commands, often changing designations, on the way.

For example, the 1st Hull Heavy Battery, initially trained with 11th (Northern) Division, and became known as the 11th (Hull) Heavy Battery. However, it left the Division in June 1915 to join 30th Division and in February 1916, transferred to 38th Brigade RGA to serve in East Africa. When they went to France in 1918, they became the 158th (Hull) Heavy Battery and later the 545th Siege Howitzer Battery, RGA. (“Heavy Artillery Groups” became known as “RGA Brigades”, from 17 December 1917, but the two terms were used almost interchangeably).

The 2nd and 3rd Hull Artillery Units, had less complicated histories. They served as Royal Garrison Artillery, with the 31st and 32nd Divisions in France, but sometimes under different Housing Group Commands, with men and artillery swapped between the two, which could be equally confusing. Similarly many Hull gunners transferred to newer artillery units, such as the 251st Siege Battery, formed on 13th September 1916, and sent to France on 5th January 1917. Many East Riding, artillery volunteers, served with the 2nd (Northumbrian Brigade), Royal Field Artillery. In 1918, there were attempts by local Officers, to pull all the Hull gunners back into one group, but it never quite worked.

In all, Hull lost 352 artillery men in the war, including 50 serving with the 251st Siege Battery. Many were wounded and discharged from the service with Malaria and other tropical diseases from the East Africa Campaign.

Recruitment, Training and Service

In September 1914, Lord Nunburnholme who was simultaneously raising the ‘Hull Pals’ Brigade (10th–13th East Yorkshire Regiments), also raised the 124th (2nd Hull) and 146th (3rd Hull) Heavy Batteries and the 31st (Hull) Divisional Ammunition Column. He opened Hull City Hall, on the 6th September 1914, as the Central Hull Recruiting Office, for all the units being raised in the city. Douglas Boyd, a Hull Corporation employee, was commissioned as Lieutenant and appointed recruiting officer. By 15 September, 80 men had been enrolled for the 1st Hull Battery, many drawn from the shipbuilding and engineering firms in Hull, while horse drivers came from the rural villages of the East Riding. It reached its full war establishment by mid-December, when it was authorised to recruit an additional depot section to supply reinforcements.

The recruits began training at East Hull Barracks on Holderness Road, performing drill in nearby East Park. The men lived at home, and until uniforms arrived the men of 1st Hull Battery were distinguished form the other East Riding recruits by wearing a red and blue armband on their civilian clothes. The battery’s guns, four Boer war -era 4.7 inch guns, arrived at Kingston Street Station in late October, and the men dragged them through the streets of Hull, first to Wenlock Barracks, th en on to East Hull Barracks.

en on to East Hull Barracks.

On 5 November, Captain Williams handed over command and reverted to the RNR (he commanded armed merchant vessels later in the war). The new CO was Temporary Captain, John McCracken, who had been an RGA Battery Sergeant Major, with 23 years’ experience at the outbreak of war.

As part of 11th Division, the battery was formally designated 11th (Hull) Heavy Battery on 1 May 1915, when it established its headquarters outside the city at the former Hedon Racecourse. Here the horse teams were lodged in the racing stables and the battery began serious training.

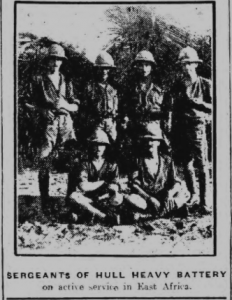

The photo (right), shows the (11th (Hull) Heavy Battery in East Africa.

They had trained with 11th (Northern) Division, but left the Division in June 1915 to join 30th Division. In February 1916 they transferred to 38th Brigade RGA and were deployed in the East African Campaign, arriving at Kilindini on the 16th March 1916. In a largely forgotten campaign, the 11th Hull Heavy Battery arrived at Kondoa Irangi in German East Africa to support General, J. L. Van DeVenter’s South African 2nd Division who had become beleaguered there. The 11th Hull Heavy Battery were led by Captain Orde Brown to relieve Van Deventer’s forces at Kondoa. The Hull Gunners are best remembered for their epic traverse of the Massai Steppe from Himo Bridge Camp, ridden with disease and weakened by hardship, taking 17 days to trek the 200 miles from Himo to Kondoa. They took up position on Battery Hill at Kondoa on the night of 3rd June 1916. Their timely arrival opposed the German East African forces led by General Von Lettow Vorbeck.

The battery returned to England aboard RMS Durham Castle, landing at Plymouth on 31 January 1918. On 1 March at Aldershot, it was re-designated 545th Siege Battery, RGA, under the command of Captain (now Major) Floyd, who set out to get back as many veterans of the 1st Hull Bty as he could from other RGA units where they had been posted from convalescence hospitals. The battery was joined by newly trained signallers from Catterick Camp, and on 2 April it moved to Lydd for training. 545th Siege Battery had arrived on the Western Front in time for the Allied Hundred Days Offensive. The success of the Battle of Amiens caused the Germans to withdraw from the Lys Salient and the battery had to move forward to new positions. It came into action at Doulieu on 20 September, at once coming under heavy Counter-battery fire. The following day it was pulled out and moved south to join Fourth Army, with which it served for the rest of the war.

St Quentin Canal

At Peronne the battery joined 47th Brigade RGA, assigned to III Corps. The gunners were unable to find suitable positions during the night of 24/25th September, and left their gun platforms beside the road under guard. During the night, one of the platforms received a direct hit from enemy fire. The guns were positioned the following night, and from 27th September took part in the preparatory bombardment for the assault on the Hindenburg Line (the Battle of St Quentin Canal) by III Corps and II US Corps. On 27th November it carried out counter-battery fire in support of the Americans’ preliminary attack on ‘The Knoll’, continuing the following day as calls for support came in from the infantry. For the main attack on 29th September, the battery fired a large number of shells on roads and bridges, as well as enemy batteries.

Fourth Army stormed across the St Quentin Canal, in large part because (as Sir Douglas Haig’s said), ‘The intensity of our fire drove the enemy’s garrisons to take refuge in their deep dugouts and tunnels, and made it impossible for his carrying parties to bring food and ammunition’.

The modern historian of II US Corps concurs: ‘Much of the success of the American 30th Division came from the work the British artillery began the day before the attack and continued until the jump-off. With trench bombardment, counter-battery fire, and a barrage that cut the wire, the artillery caught the Germans in their dugouts and caused numerous casualties among their units. German prisoners captured by units of the 30th Division substantiated this fact by telling their interrogators that the barrage caused heavy casualties’

Beaurevoir Line

The firing continued on 1st October, as III Corps was relieved by XIII Corps to continue the offensive. The battery targeted Usigny Dump, a German stores depot masked in a dip in the ground some 6 miles (9.7 km) away. It also fired on strong points at Villers Farm, Élincourt and Serain, and roads around Villers-Outréaux and Malincourt. The battery then moved up to Ronssoy to join the howitzers of 47th Bde to support XIII and Australian Corps‘ attack on the Hindenburg Support Line (the Beaurevoir Line) between 3–5th October.

Getting the artillery forward following these victories proved difficult, but 545th Siege Bty’s Right Section was attached to ‘Roberts Brigade’, an ad hoc formation organised for the pursuit, and continued its bombardment on 10 October from Maurois railway station. Left Section suffered from a German air raid on the night of 9/10th October, without casualties. While Right Section followed the advance, Left Section manned a brigade ammunition dump at Maretz.

Selle

The pursuit ended at the River Selle. For its assault crossing of the river on 17th October (the Battle of the Selle), XIII Corps had its 6-inch guns, including 545th Siege Bty (now in 73rd Army Brigade, RGA), sited well forward so that they could hit the crossings over the Sambre Canal, which carried the German lines of supply (and retreat). The assault went in behind a massive bombardment, the attacking infantry crossing the Selle by means of duckboard bridges. By the end of the day, Fourth Army had forced its way across the Selle and broken into the German Hermann Stellung I defences. Over succeeding days, it closed up to the Sambre Canal.

545th Siege Battery’s guns had now fired so many rounds that their barrels required re-lining, and were sent to the Ordnance Deppot at Amiens on 27th October, thereby missing the Battle of the Sambre. Meanwhile, the personnel and the ammunition column moved forward to Le Cateau. During the night of 27/28 October their position came under heavy fire from German artillery, and ammunition lorries were set alight. Serjeant Goodwin (ASC) and Lance Bombardier, Frank Dickens (545th Bty) were awarded the Meritorious Service Medal for their gallantry in throwing shells from a burning lorry. In the confused pursuit, one of the ammunition lorries was accidentally driven into No Man’s Land and had to be abandoned until the enemy retreated.

Disbandment

On 5 November, 1918, all heavy artillery batteries in XIII Corps’ area were stood down and the men were billeted in Le Cateau. When the Armistice with Germany came into effect on 11th November, 1918, 545th Siege Bty handed over three of its re-lined Mk XIX guns to 189th Siege Bty, which went forward as part of the Army of Occupation, receiving older Mk VII 6-inch guns in exchange. The battery moved to Saulzoir in December, where it carried out salvage duties. Demobilisation began at New Year, and the men were progressively sent to Clipstone Camp in Nottinghamshire, where the last group of men from the original 1st Hull Battery were demobilised on 31 July 1919.

The story of Hull’s 2nd Heavy Battery, the 124th Royal Garrison Artillery, is summarised in this useful link: https://www.wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/allied/rgartillery.php?pid

The story pf Hull’s 3rd Heavy Battery, the 146th Royal Garrison Artillery, is summarised below.

To Western Front June 1916. Served in France under various Heavy Artillery Groups (HAG),

12 Heavy Artillery Group (HAG) – 20.6.16

Lorings Group II Anzac Corps – 15.7.16

55 HAG – 29.7.16

39 HAG – 29.7.16

IX Corps Heavy Artillery Group – 29.5.17

66 HAG – 9.6.17

73 HAG – 26.6.17

28 HAG – 7.7.17

35 HAG – 10.9.17

42 HAG – 3.1.17

16 HAG 20.12.17 No subsequent change

Made up to 6 guns 6.10.17. One section joined from 172 Heavy Battery

In addition, to Hull’s three Heavy Batteries, there were other artillery, such as;-.

The East Riding Royal Garrison Artillery, formed by Lt Col, Robert Hall to defend the City and Humber Estuary. It was based at Spurn Point, but as part of the 2nd Northumbrian Brigade, its Head quarters, were located at Hull’s Wenlock Street Barracks, and it shared Hull’s Londesborough Street Barracks. The East Riding RGA’s wartime role, together with other TF and Regular RGA units, was to man guns defending major ports on the North East Coast of England. It was responsible for the four 6-inch and four 4.7-inch guns of the Humber defences under No 15 Coastal Fire Command (Spurn Point) and No 16 Coastal Fire Command (Hull). The following Links provides more on their role. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Riding_Royal_Garrison_Artillery#:~:text=The%20East%20Riding%20Royal%20Garrison,the%20East%20Riding%20of%20Yorkshire.

The East Riding Fortress Engineers, formed and commanded by Lt Col E M Newell. On the outbreak of the war, the TF was mobilised and the fortress engineers took up their war stations in the North Eastern Coast Defences. TF units were invited to volunteer for Overseas Service and on 15 August 1914 the War Office issued instructions to separate those men who had signed up for Home Service only, and form these into reserve units. On 31 August, the formation of a reserve or 2nd Line unit was authorised for each 1st Line unit (prefixed ‘1/’) where 60 per cent or more of the men had volunteered for Overseas Service. Although the East Coast was attacked by the German High Seas Fleet on 16 December 1914 (the Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby) and again on 24 April 1916 (the Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft), and was regularly bombed by Zeppelin airships, the fortress engineers were nevertheless able to release 1st Line men to provide 1/1st East Riding Field Company, RE for active service in the field. A 581st (Humber) Fortress Company was also formed, about which little is known. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Riding_Fortress_Royal_Engineers#:~:text=The%20East%20Riding%20(Fortress)%20Royal,units%20in%20both%20World%20Wars.

The 2nd Northumbrian Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, led by Lt Col, J B Moss, DSO. It was formed in Hull in April 1916. In August 1917 it was converted into 8th Battalion of Royal Defence Corps.

-

- Comprised of Brigade Headquarters, 1 and 2 East Riding Batteries (all based at Anlaby Road, Hull), North Riding Battery (Scarborough and Whitby) and Brigade Ammunition Column (Park Street, Hull)

- 23 November 1915: re-armed with 18-pounder field guns

- 11 May 1916: D Battery was formed

- 10 May 1916: the Brigade Ammunition Column left to be merged into the Divisional Ammunition Column

- 16 May 1916: the brigade was renamed to CCLI (251) and the batteries lettered A, B and C

- Same date: D Battery left to go to 253 Brigade and became its B Battery

- Same date: 5 Durham (Howitzer) Battery joined from 253 Brigade and was renamed as D (Howitzer) Battery

- 16 November 1916: B Battery and half of C Battery joined from 253 Brigade and were broken up to bring A, B and C Batteries up to six guns each

- 16 January 1917: a two-howitzer section joined from D (Howitzer) Battery of 252 Brigade was merged into D (Howitzer) Battery to bring it up to six howitzers.

East Riding RGA -8 inch, howitzer, in action, September 1916.

Sources:

Hull History Centre (Ref: C DMX/330/1) – an album compiled and presented by Major R. Saunders R.A. to Major Robert Hall & Officers, East Riding R.G.A. as a record of the Corps during the 1914-18 War, commencing August 1914. Includes a history of the East Riding R.G.A. during mobilization, photos of Corps Officers with a record of their Military careers, Names of all ranks who proceeded overseas, and a record of other Officers who did duty. The front of the album contains a summary of the war giving details of men from the Corps who lost their lives, those who were wounded, those that were decorated, and those mentioned in despatches. The volume also contains Officer photographs:

Also useful links below:

https://military.wikia.org/wiki/1st_Hull_Heavy_Battery,_Royal_Garrison_Artillery#cite_note-11

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_Hull_Heavy_Battery,_Royal_Garrison_Artillery

https://www.wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/allied/rgartillery.php?pid=

http://www.wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/allied/rga11heavybty.php#sthash.9YUWNdHu.dpuf)

First part of six sections of a recording of a long interview with L.J. Ounsworth, Royal Artillery (interviewer unknown). Length 30 mins approx, includes: training at Hedon Race Course, Hull after joining up as a signaller. They completed two years of peace time cavalry training within six months. Continues directly into the second part.

http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/gwa/document/9404?REC=1