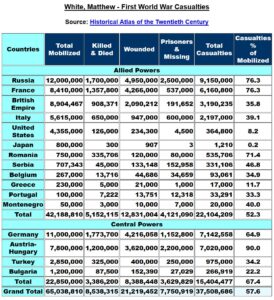

Calculating war casualties can be a complex, sometimes controversial subject. However, it is widely accepted that about 10 million military personnel and about 7 million civilians died in World War 1, with some 23 million wounded – an estimated casualty total of 40 million people. All these were individuals with families and a life history.

The Entente Powers (also known as the Allies) lost about 6 million soldiers, while the Central Powers lost about 4 million. At least 2 million died from diseases and 6 million went missing, presumed dead. About two-thirds of military deaths in World War I were in battle. This was unlike any previous conflict during the 19th century, when the majority of deaths were due to disease. Improvements in medicine, as well as the increased lethality of military weaponry, were both factors in this development. Nevertheless disease, including the ‘Spanish flu’, still caused about one third of total military deaths for all belligerents.

Britain and Commonwealth forces lost nearly 900,000 military personnel and 1.7 million men were wounded. Britain also lost 16,829 civilian dead, 1,260 civilians were killed in air and naval attacks, 908 civilians were killed at sea and there were 14,661 merchant marine deaths. Another 62,000 Belgian, 107,000 British and 300,000 French civilians died due to war-related causes.

British Losses

The House of Commons, in May 1921 reported that the UK Great War dead numbered 743,702. It is estimated some 1.7 per cent of the total UK population at the time died, in the First World War.

In Britain that was about 10% of the male population killed, and 70% of these men were aged between 20-24 years old. Of the 740,000 British war dead, no fewer than 71% were between the ages of 16 and 29 years. The Commonwealth War Records reveal that 14,108 British soldiers died aged 18 years or younger.

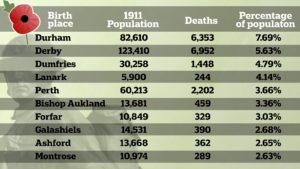

Research shows the level of loss was significantly higher in some areas than it was in others. Durham for example, tragically lost nearly eight per cent of its population during the First World War, with Derby (5.64%) and Dumfries (4.79%) also badly affected. There were over a hundred families in Hull that lost two or more from the same family. At least ten Hull families lost three sons and four Hull families, lost four sons.

Throughout the United Kingdom, one in six families suffered a direct bereavement, 192,000 wives had lost their husbands, and nearly 400,000 children had lost their fathers. A further 500,000 children had lost one of more of their siblings. Appallingly, one in eight wives died within a year of receiving news of their husband’s death.

The First World War cost Britain, a large number of young men and certainly some high achievers, in a short space of time. Some individual families were particularly devastated. These include the sacrifice of:-

– Annie and William Souls, from Great Rissington, Gloucestershire, who lost five of their six sons, in the First World War.

– James and Susannah Harman, from the Oxfordshire town of Watlington, who also lost five sons.

– Canon, William Shuckforth Grigson, from Pelynt, Cornwall, who lost five of his seven sons.

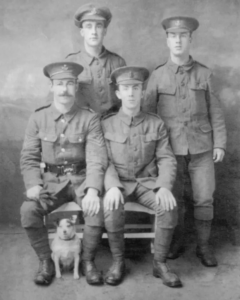

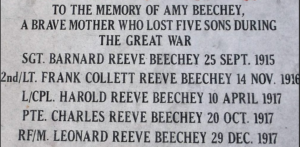

– Mrs Amy Beechey, from Avondale Street, Lincoln, who lost five of her eight sons and another badly wounded.

– Mrs Martha Elizabeth Baldock-Apps, from Hurst Green, Sussex, who lost five of her seven sons.

– Margaret Smith, from Barnard Castle, County Durham, who had five sons killed in quick succession.

– John Henry Williams, a shepherd, from Lydd, Kent, who lost four sons, in the war.

– Thomas Waites Tomlinson, a farm Labourer from North Frodingham, Driffield, lost four of his six sons.

– The Beatham family from Penrith, Cumbria, whose son Robert, was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, and another three died of disease during the war.

– Mrs Sarah Parnell, from 46 Park Drive, Worthing, Sussex, who saw three of her four sons, Charles, William and Alfred Parnell, killed together, on the same day – 30th June 1916.

– Similarly, Thomas and Sarah McGee, from Ely, Cambridgeshire, lost four sons in the war, with three of them killed on the 12th October 1916.

– Annie Lowings, from 46 Sedgewick Street, Cambridge, also lost four sons in the war.

– The three Racheil brothers, from East Ham London, all served with 3rd Royal Fusiliers and were killed at Hooge, on 24 May 1915 – Arthur (born 1894), Frank (born 1897) and Frederick (born 1891).

– Edward, Frederick and William Urry, from Newport on the Isle of Wight, served in the 1/8 Hampshire Rifles (the Isle of Wight Rifles) and were killed together, at Gallipoli, on 12th August 1915. In addition to the loss of their three sons, Edward’s wife, Florence also suffered the loss of William Richardson, her brother, on the same day and in the same action.

– The Mochrie family from Kilbirnie in Ayrshire would suffer the loss of three brothers – James, Robert and Matthew Mochrie served in different Scottish regiments, but all were killed at Loos, on 25th September 1915. A fourth brother, Andrew Mochrie, would be killed later in the war on 9th June 1917.

– At Jutland, on 31st May 1916, three Malcolm brothers – Charles, Joseph and John – were serving as stokers and lost on HMS Queen Mary.

– Three brothers, Ernest, Fred and Charles Walker, serving in the Barnsley Pals battalions of the York and Lancashire Regiment, were killed at Serre, on 1st July 1916. Ernest in the 13th battalion (1st Barnsley Pals), and Fred and Charles in the 14th (2nd Barnsley Pals).

– Bertie, James and Thomas McGee, from the village of Stuntney, near Ely, would all be killed on 12th October 1916, in different engagements on the same day. A fourth brother, Edward (born 1892) would die of wounds on 9 August 1917.

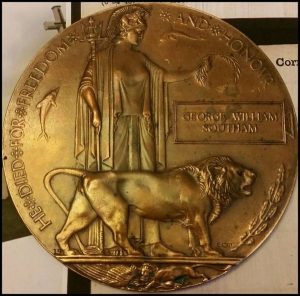

These stories of sadness are not exhaustive and were replicated in different armies, throughout the world. It is difficult for a modern audience to quite understand the suffering caused by the First World War. Millions of people, throughout British society, grieved for a lost loved one. The national, collective grief, haunted generations for decades. It still resonates, as shown by the continued, solemn reverence, displayed at war memorials today.

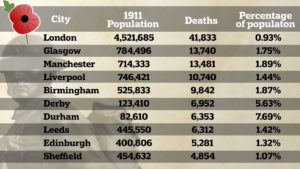

Along with the WW1 dead, were the 1.7 million British wounded. By October 1922, the Ministry of Pensions was paying 900,000 pensions to disabled ex servicemen. These wounded included 80,000 gas victims, 30,000 made deaf, 80,000 with ‘shell shock’ and some 250,000 amputees. The wounded increased over time. By the end of 1928, nearly 2.8 million war veterans received a disability pension of some sort. While it was the big cities that lost the highest numbers of men, it was the smaller northern England and Scottish towns that were decimated by particular battles.

Yorkshire remembers the First Day on the Somme, more than most, partly on account of its disproportionate losses. According to Martin Middlebrook, Yorkshire suffered more than any other regional area, with 9,000 casualties, that is, 3,000 more than Ulster or Lancashire, and 3,500 more than, the North-East or Scotland. Each Yorkshire regiment contributed a unit, ranging from a single battalion to the ten battalions of the West Yorkshires, and, collectively, the 29 Yorkshire battalions represented 20 per cent of the 143 involved. Leeds and Bradford each suffered casualties in excess of 1,000, Sheffield many hundreds of casualties, and six Yorkshire battalions, out of 32 overall, incurred casualties in excess of 500 among officers and other ranks. These were the Sheffield City Battalion (512), 1st Bradford Pals (513), Leeds Pals (528), 8th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, (539), 8th York & Lancaster (597), and the 10th West Yorkshires (710, the highest number suffered by any British unit, representing 90 per cent of those who went over the top on 1 July). Southern counties also suffered. “The Day Sussex Died” refers to 30th June 1916, when 1,100, or 60% of “Southdowners” were killed or wounded, at Ferme du Bois near Richebourg. It was a futile, diversionary attack, on a defensive position known as the “Boers Head” and does not even appear in the Official Military History.

Britain’s big cities lost most men, Glasgow, 13,740; Manchester, 3,481; Liverpool, 10,470; Birmingham, 9,842; Hull, 7,500 +, Derby, 6,952; Edinburgh, 5,281; Durham, 6,353; Leeds, 4,312; Sheffield, 4,854; and London, 41,833. But it was the Northern and Scottish towns that saw their populations hardest hit. In Durham 6,300 men lost their lives. This was equivalent to almost two in ten men in the city and nearly eight per cent of the total population. Another Country Durham town, Bishop Auckland, was also hit hard losing more than six per cent of just 13,600 people, all of them men between 18 and 50-years-old. Derby lost almost six per cent of its population and Dumfries, Scotland, five per cent. According to genealogy company Ancestry, nine of the 10 towns and cities that lost the highest proportion of their population are in Northern England and Scotland.

Scotland

Scotland which traditionally provided recruits for the British army’s elite regiments, saw 557,000 men enlist during the WW1. Glasgow alone raised 26 new battalions and probably lost 18,000 men in total. Taking account of those Scots, already serving in British regiments and Scots who fought for other Dominions (Canada raised 16 Scottish infantry battalions), perhaps some 800,000 Scots served during WW1.

While casualty figures are still contested and vary widely, Scotland officially lost 134,712 men during WW1, about 3.1% of Scotland’s population. (Recent research suggest this figure was nearer 148,000 men, when Scottish nurses, 500 munition workers, Merchant Navy and may others are included.) This was over 25% of those that volunteered and more than twice the UK average rate of fatalities. It is said that only the Serbs and Turks had a higher proportion of participant deaths than Scotland.

Large Scottish towns, like Dumfries and Perth suffered terribly, but lowly populated places, such as the Isle of Lewis (1,000 men), Shetland (700) and Harris, sustained some of the highest proportional losses of any place in Britain. At Festubert, on 17 May, 1915, for example, there were 5,000 Scottish causalities and Historians believe more Highlanders were killed on this day, than at Culloden. Similarly, some 30,000 Scots, fought at the Battle of Loos, in September 1915 and over 7,000 were killed. At Arras, between April 9 and May 15. 1917, it is estimated that another 18,000 Scots died.

Almost every town and village in Scotland was affected by these losses. Their local memorials bear testimony to these sacrifices. They include the Anderson’s from Glasgow, who lost all their four sons, the last one, William Anderson earning the Victoria Cross. Peter and Elspeth Tocher, from Aberdeen, who lost five sons, in the war – all were Gordon Highlanders. Also Elizabeth Cranston, from Haddington, East Lothian, who lost four sons, with another two badly wounded. Mrs Cranston later moved to Sydney, Australia, in 1920 to start a new life, only to live out her days in a psychiatric hospital. She would often be seen waiting on a platform at the nearby railway station, tragically telling passing travellers she was ‘waiting for my boys to come home’. In echoes of the film “Saving Private Ryan”, Elsie Cowan, from Glasgow, pleaded for her son Frank to serve at home because four of her sons had already gone to war and three had been killed in 1915. The fourth was wounded. The Lothian and Peebles Military Appeal Tribunal granted Frank Hamilton Cowie exemption for the rest of the war on the grounds of hardship and he was recalled from service in France.

Ireland

In Ireland, the First World War was a complex and painful episode in Irish History. According to Irish government archives, nearly 80,000 men enlisted into the British army during the first 12 months of the war. Some 134,202 Irish men were recruited in Ireland during the war. They joined 58,000 Irishmen who were already serving in the army.

While conscription was never imposed on Ireland, some 206,000 men from Ireland fought in the war, serving in many global battles. About 37,000 died serving in Irish regiments of the British forces, about 2,5% of the the male population of Ireland at the time. In all about 49,400 Irishmen died during WW1, fighting, for other British Regiments and other countries, such as Canada, Australia and the United States. Their dead included six Irish International rugby players, the poet, Francis Ledwidge, the famous Irish Hockey player, JG Anderson, Irish Golfer, Michael Moran, 3,500 Irishmen killed on the Somme, and 3,411 serving in Irish Regiments at Gallipoli.

Recent research, has found at least 37,091 fatal Irish casualties. North east Ulster was the hardest hit, followed by Dublin and Cork, while the rural midland counties were the least affected. Cities, such as Dublin lost 4,973 men or 3.69% of the male population. Counties such as Antrim, (which is home to most of Belfast), lost 5,122 men (3.37%), Cork, 2,226 men (2.01%), Down, 2,056 men, (3.98%), Londonderry, 1,343 men, (3.81%) and Armagh 1,128 men (3.74%). Among the many losses were the six Collins brothers from Balteen, Waterford, From a large, Catholic, working class family, they volunteered to serve in British Army. Four of the six soldiers were killed in battle and the youngest died just 16 years old. When their grieving mother received a telegram to say that a fifth son was missing, presumed dead, the sixth soldier was sent back to her.

WW1 remains a much debated topic in Ireland. For Ulster unionists it represented a great sacrifice on behalf of Britain, earning them the right to opt out of Irish self government. For Irish Nationalists, participation in the war was largely seen as a mistake following Independence in 1922 and superseded in popular memory by the struggle for Independence from 1916 to 1921. However, there were popular commemorations by Irish veterans up to the 1940s and the Irish Free State paid for the national war memorial in Dublin.

(https://www.theirishstory.com/2015/03/25/reconsidering-irish-fatalities-in-the-first-world-war/#.Xuyk0GhKiUk)

Wales

In Wales, between 20,000-40,000 Welshmen, died on active service in the Great War. Among the 6,000 Cardiffians commemorated on over 100 memorials in Cardiff, are the 121 men of the Whitchurch Parish, including the Welsh Rugby winger, Captain, Johnny Lewis Williams, killed at Mametz Wood in July 1916. Modern research suggests another 94 men could have been added to this Whitchurch memorial, but were excluded for various reasons.

The attack by the 38th Welsh Division, on Mametz Wood, between 7th-10th July 1916, saw some 4,000, Welsh casualties. Passchendaele, saw another 3,000 Welsh Casualties, including, Welsh poet Hedd Wyn – Private, Ellis Humphrey Evans, killed at Pilkem Ridge, on 31st July 1917.

Reginald George Lewis was just 14 when he died on August 6, 1918. From Vale Street, Barry, he is the youngest recorded Welsh casualty of WW1. Harold Jenkins, from Werfa Street, in Roath, Cardiff was just 15, when he died on 1st March, 1917, St David’s Day.

In Cardiff, there were 2,900, recorded deaths with 27 young men killed at Mametz Wood, on the 7th July 1916. There were 353 recorded deaths of people from Llanelli and 1,277 from Newport. The Carmarthen County Memorial includes 2,000 men and women killed in the Great War. The Pembrook Count Memorial, commemorates, 1,354. In Ceredigion, which has no County memorial, another, 1,400 died in the war. There were probably many more deaths, but were ineligible for commemoration due to CWGC and Ministry of Defence rules on date and cause of death and lack of war related evidence.

As a major coal producer, WW1 had a profound impact upon Wales, destroying many estates of the landed gentry. There was also a huge migration of women away from Wales and a rapid decline in organised Welsh religion.

http://war-memorials.swan.ac.uk/?page_id=4

Almost every UK Town affected by WW1.

In an October 2013 update, researchers identified only 53 civil parishes in England and Wales from which all serving personnel returned from WW1. These became known as “Thankful Villages”. There are no “Thankful Villages” identified in Scotland or Ireland, yet all of Ireland was then part of the United Kingdom at the time.

According to the research by the genealogy company Ancestry, the 10 UK towns that lost the highest percentages of their populations in the First World War are shown below: –

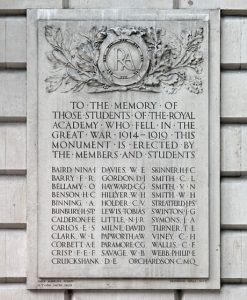

Although the great majority of casualties in WW1 were from the working class, the social and political elite were hit disproportionately hard by WW1. The sons of the “middle Class”, provided the junior officers that were expected to lead from the front. 17% of officers were killed in WW1, compared to 12% of the British army’s other ranks. Some 35,000 former public school boys died in the war, about a fifth of all those who served. Eton School, alone lost more than 1,157 former pupils – 20% of those who served. Other schools, such as Charterhouse lost 700, Malvern College 429 from the 2,348 that served. Manchester Grammar lost 521 former pupils, and King Edward’s, in Birmingham, lost 247, from the 1,400 ‘boys’ that served, including 52 in the 1916 Somme Offensive. Cheltenham College lost 264 men and Brighton College,149. Universities were similarly affected by WW1. In November 1918, the University of Liverpool recorded 1,640 names on its Roll of Honour, including 176 fatalities and many others missing. Similar lists were maintained in every university. The exact number of casualties from UK universities is uncertain, but the numbers were awful. Estimates suggest that Oxford University (14,561 men served), lost 19%, Cambridge University, 13,878 served and 2,470 killed (18%), Manchester University (600) and Glasgow University (770), both 17%.of those serving, killed. Aberdeen University, lost 351 men, or 12%, from the 2,852 men who served, Edinburgh University lost 944 men in the war. Leeds University, 361, Newcastle 223, to list just a few. The lost potential of these men can will never be known.

The British Aristocracy was devastated also by the war, with 47 Peers killed and six of these, leaving no brothers to succeed them. By 1915, 9 House of Lord Peers and 95 sons of Peers had been killed in the war and it was to get worse. In all, 22 Members of Parliament and 24 Peers from the House of Lords, died in WW1. The UK wartime Prime Minister Herbert Asquith lost a son, while future Prime Minister Andrew Bonar Law lost two sons. Anthony Eden lost two brothers, another brother of his was terribly wounded, and an uncle was captured. In all Britain lost 750,000 men in the war. More than 300,000 have no known grave and are commemorated on memorials to the missing; there are seven in Belgium and 22 in France. Those they commemorate were Regulars, Territorials, volunteers and conscripts, aged from fourteen to sixty eight and ranging in rank from private soldier to Lieutenant-General.

France

In France, where much of the war raged, approximately 11% of the entire population, was killed or wounded during the war – about 1.4 million men and another 300,000 civilians.

The 1.4 million military casualties, included 58,000 soldiers from French colonies, 11,400 naval deaths and the 28,600 deaths recorded by the army medical corps in the six months after the war.

Some French regions suffered more than most. For example, In Brittany, one million Bretons enlisted during World War I. A quarter of them never returned. Bretons were killed and wounded at a rate twice the national average.

Some 27,000 French soldiers died in a single day, on 22nd August 1914. Known as the Battle of the Frontieres, five French Armies, fought on that same day as part of 15 different assaults, with no coordination between them. In each case, the French lost much ground and left many of their wounded behind because they were not adequately trained in defensive warfare and because their artillery was badly exploited. This Battle is now forgotten, but remains France’s highest ever death toll in a single day. In eleven months of fighting at Verdun in 1916, 163,000 French soldiers were killed and 216,000 were wounded.

It is estimated that 4.2 million French men were wounded in WW1 – a casualty rate of 74% of all those mobilized in the French Empire. This included:-

-

1,100,000 disabled

-

300,000 mutilated

-

42,000 blinded

-

15,000 broken faces

About a third of all French wounded men received a long-term disability pension. Among them was Albert Severin Roche (1895–1939), wounded nine times, he became France’s most decorated Private Soldier and personally captured 1,180 prisoners.

In addition to the military casualties, deaths of civilians by artillery in the battle zone, or in the back areas by aircraft were frequent. France lost 300,000 civilians killed by military operations and food shortages, and 200,000 by the Spanish Flu. Civilian dead include 1,509 merchant sailors, and 3,357 killed in air attacks and long range artillery bombardments. France left behind 600,000 widows, 986,000 orphans, and 1.1 million war invalids. Over ten percent of the male population of France had been wiped out, a figure that rises to 20% for the ‘under 50’ age group. The war mainly killed young men. 36% of the soldiers aged between 19 and 22 were killed. Of the 470,000 males born in France in 1890, and who were 28 years old when the war ended, half were killed or seriously wounded.

The fighting heavily handicapped the national production system, infrastructure and buildings. The assessment undertaken at the end of the conflict was substantial: 712,000 buildings (that is 7.5 percent of the entire building park, including houses, industrial agriculture, buildings, etc. in 1914) and 20,000 industrial compounds were destroyed or damaged; 2.5 million agricultural hectares were devastated; 2,000 kilometres of canals and 2,000 bridges were destroyed, as well as 62,000 kilometres of road and more than 5,000 kilometres of railroads were out of order in all of France. In the agricultural sector, grain crops in 1919 were half the size of those from between 1910 and 1913. Beet crops were one-fifth of pre-war levels, while forage plant crops were only two-thirds the size of pre-war levels.

On the Battlefields, some 7.5 million acres of French land had been destroyed by explosives and chemical warfare. The Western Front along 250 miles and 25-30 miles wide had been reduced to a wasteland. 1,659 towns and communes had been blotted out, 2,363 others were wrecked, and 630,000 houses were destroyed or seriously damaged. In France, around 350,000 houses were destroyed, along with 11,000 public buildings and 62,000 kilometres of railway lines. So many mines were ruined, that the output of coal was reduced by a half. 21,000 factories were gutted, and the great manufacturing centres at Lille, and the Longwy district, were systematically despoiled of machinery vital to their prosperity. An area of about 116,000 hectares, or 460 square miles of land, in France, was declared a “Red Zone”, forever deemed uninhabitable, due to WW1 activity. The area today remains saturated with unexploded shells, grenades, and rusty ammunition. Soils are heavily polluted by mercury, chlorine, arsenic, various dangerous gases, acids, human and animal remains. The area is also littered with ammunition depots and chemical plants. Deaths still continue today, due to unexploded munitions in the Western front area. The situation is similar in Belgium, where in 2022, the DOVO, the explosive ordnance disposal unit of the Belgium Army, made 2,300 interventions and destroyed 166 tonnes of ww1 munitions.

Italy

In 1915, Italy had signed the secret Treaty of London. In this treaty Britain had offered Italy large sections of territory in the Adriatic Sea region – Tyrol, Dalmatia and Istria. Such an offer was too tempting for Italy to refuse. Britain and France wanted Italy to join in on their side so that a new front could open up the south of the Western Front. The plan was to split still further the Central Powers, so that its power on the Western and Eastern Fronts was weakened. The plan was logical. The part Italy had to play in it required military success. This was never forthcoming. Between 1915 and 1917, Italy fought at least 12 battles, on a 60 mile front, along the Isonza river. These battles resulted in over 650,000 Italian casualties and 420,000 Austrians, a carnage as great as anything seen on the Western Front. The Italians only got 10 miles inside Austrian territory. But in October 1917 came the disaster of Caporetto. In this 12th battle, the Italians had to fight the whole Austrian Army and 7 divisions of German troops. The Italian Army lost 300,000 men. Though the Italians had a victory at Vittorio Veneto in 1918, the psychological impact of Caporetto was huge. The retreat brought shame and humiliation to Italy.

By the end of the war in 1918, 600,000 Italians were dead, 950,000 were wounded and 250,000 were crippled for life. The war cost more than the government had spent in the previous 50 years – and Italy had only been in the war three years. By 1918, the country was hit by very high inflation and unemployment was high. The Italians did not get what they felt had been promised at the Treaty of London and that caused resentment especially at the losses Italy had endured fighting for the Allies. The Italian government was seen as weak and lacking pride. This prompted the rise of Italian Nationalism and Mussolini in WW2.

Austria and Hungary

The exact number of Austro-Hungarian military and civilian war losses during the First World War remains unknown to the present day as the successor states did not cooperate with one another to arrive at reliable figures after the war. After the war, three people were active in calculating war losses. Wilhelm Winkler (1884-1984) who was a population-statistician in a military office during the war and worked with civilian losses after the war. Gaston Bodart (1867-1940), a Viennese statistician and military historian. Edmund Glaise-Horstenau (1882-1946), a regular officer throughout First World War, who published an official Austrian history of the First World War, which appeared in 1930-1938 in seven volumes. Estimates of the total losses of the Austro-Hungarian armed forces range from 1.1 to 1.2 million, with largest losses in the Galicia, Bohemia, Moravia and Styria.

In addition there were 450,000 deceased prisoners of war (385,000 died in Russian captivity; 35,000 in Italian POW camps; 30,000 in Serbia and 3,000 died in Romania). There were also approximately, 300,000 soldiers who stayed missed after war.

The number of direct and indirect civilian losses is completely unknown. Direct losses, are estimated at 1,800 civilians who served with the military, a large, but uncounted number of civilians who died in war zones, perhaps another 80,000 civilians executed by the Austrians during their brutal reoccupation of territories and another 550,000 refugees, who suffered more than most, due to undersupply and health epidemics.

Indirect losses for Austria-Hungary can be estimated at 460,000 (351,000 from Austria, 82,000 from Hungary and 32,000 from Bosnia). These were caused by famine,(Austria lost her main grain producing area, Galicia, quickly and for the entire war); cold, (there were three bitter winters between 1915-1917) and epidemics (the Spanish flu additionally caused 250,000 victims). The effects of First World War were lingering: especially in the Austrian Republic, undernourishment and poverty remained a problem. Altogether the losses of Austria-Hungary can be estimated at about 2.4 million, or 46.1 per thousand of the population in 1910.

)See https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/war_losses_austria-hungary)

German Losses

In Germany, approximately 13 million Germans served in the military during the Great War; over 2 million or 15 percent of these, were killed. About 14 percent of those killed were enlisted men and 23 percent of German officers were killed in the war.

About 465,000 German soldiers died each year of the war. German losses were worst in 1914, the first year of the war, and September 1914 was the bloodiest month of the whole war, when German units suffered losses of about 16.8 percent. In August and September 1914, according to the Sanitätsbericht, 54,064 German soldiers were killed, and an astonishing 81,193 went missing. In 1914, losses on the Eastern Front were actually higher than on the Western Front, though very quickly the situation was reversed, and deaths in the west were regularly higher than in the east. Jewish Germans died at the same rate as non-Jewish Germans (this would become a heated issue in the 1930s) – Some 100,000 Jewish Germans served in the war and 12,000 Jewish Germans died in the war. Death by bayonet was very rare; poison gas killed about 3,000 German soldiers. Artillery was by far the greatest killer in the war; about 58.3 percent of German deaths were caused by artillery and about 41.7 percent by gunshot. By far the bloodiest battle, for Germans, during the war was the set of battles known as the “Kaiserschlacht,” the “Kaiser’s Battle,” or the “Ludendorff Offensive” in the spring of 1918, when the German army suffered 303,450 casualties in a matter of weeks. Verdun was the second bloodiest battle, when the German army lost, killed and wounded some 200,000 troops.

A summary of World War I casualties, complied by the U.S. Public Broadcasting Service, lists 1,773,700 German war dead, 4,216,058 wounded, 1,152,800 prisoners for a total of 7,142,558 casualties. This was a casualty rate of 54.6 percent of the 13,000,000 soldiers Germany mobilized for the war. Based on these estimates, Germany’s total casualty figure is second only to Russia’s, 9,150,000 killed, wounded, prisoners and missing.

After the war, the German Government reported that approximately 763,000 German civilians died during the war because of the Allied Blockade and another 150,000 died of the war-related Spanish Influenza. Total German losses, then, military and civilian, during the Great War, thus approach 3 million.

The German dead and wounded were a demographic catastrophe for German society. Some 13 percent of German men born between 1880 and 1899 (prime candidates for service in the war), were killed between 1914 and 1918. For German women in the doomed cohorts born between 1880 and 1899, war losses meant transformed lives. For many young German women in the 1920’s, marriage and family were not possibilities; there were no young men available. While this produced a kind of autonomy for the women affected, for those who had hoped for marriage and family, wartime deaths meant a lifetime alone. The Naval blockade of Germany food supplies which did not end until the Peace Treaty was signed in 1921, caused serious physical and psychological damage. Between 1915 -1918, there were over 760,ooo excess deaths recorded in the German civilian population, much of it from malnourishment and diseases like tuberculosis, which were related to nutrition. Many Germans lost 15-25% of their body weight during the war. Many Inmates of jails, asylums and other institutions, where food was rationed, starved to death. Even by 1921, more than 50% of Urban children were malnourished and German children were on average 3-5cm shorter than in 1914. Death rates among women were proportionately higher, because they gave their ration to their children in an effort to save them. While starvation was a major factor in concluding the war, it caused untold suffering, injustice and bitterness in German Society.

The sudden and violent death of some 2 million young men and one million civilians, confronted Germans with that peculiar 20th century phenomenon, of mass death. The apocalyptic German experience of 1914-1918, coupled with defeat, revolution, and then civil war, engendered what Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) called “absolute despair” and that obsession with messianism, apocalypse and redemption became characteristic of Weimar Germany’s culture and politics. Jason Crouthamel has explored the psychiatric dimension of this enormous trauma.

The most unexpected social consequence of the German losses, were the enormous numbers of disabled veterans and war widows and orphans desperately in need of care and often unable to care for themselves. In 1919, the newly formed Weimar Republic, on the verge of wild inflation, bankruptcy, and political chaos, discovered that it was suddenly responsible for some 2.7 million disabled veterans, 1,192,000 war orphans, and 533,000 widows. Almost all of these people were younger than thirty; and the new German Republic might be responsible for them for another half-century or more. Caring for these war victims proved to be an endless nightmare. Simply calculating the cost for war victims’ care was bitterly contentious. How much exactly, in Marks, was a missing leg worth? Was an eye shot out worth more than a shattered hand? Should compensation be based on medical condition alone and ignore social class, so that former bankers and former farmers each received the same pension for the same medical condition, or should compensation take social condition into account and be designed to help keep pensioners in the social class from which they came and thus help stabilize the existing class system? Eventually, the latter became government policy. Should the veterans’ pension system be autonomous or should it be merged with the already existing social welfare system? Eventually the two were merged, much to the outrage of many veterans who thought that being placed in the same category as welfare recipients was demeaning. Did psychiatric illnesses – combat fatigue and what later generations would describe as post-traumatic-stress-disorder – merit compensation? Generally, the answer throughout the 1920s was “no.” Even after the Reichsversorgungsgesetz (National Pension Law) of 1920 was adopted, and the pension costs were calculated, the angry debate about war victims continued to rage. By 1923, for example, the National Pension Court, which was supposed to decide controversies about pensions, had a backlog of 43,186 cases. War victims – disabled veterans, widows, and orphans – tried to organize themselves into a single pressure group, but given the fractures of Weimar society, that proved impossible. Social-Democratic, Communist, and Nationalist groups emerged; sometimes they cooperated with each other; more often, they did not.

Dealing with 3 million dead and the 2.7 million wounded was compounded by an inability to mourn those lost. For Germans, during and after the war, simply finding the bodies of the war dead, and burying them properly was a vast problem. The Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgraberfursorge (VDK), the German equivalent of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, was not instituted until 1919, so during the war there was no standardisation of head-stones or Friedhof (cemetery) construction, with the result that German memorials represent a variety of styles and levels of skill. After the war, all German burials were consolidated into the sombre cemeteries which reflected the nation’s attitude to death and which often featured especially commissioned sculptures. There remain some striking German memorials and sculptures on the Western Front, which were created both for specific units and individuals. Many lie in remote and isolated locations. Sadly many of these memorials show signs of vandalism and even traces of recent damage by hunting rifles as witnessed by the memorial in Azannes. The VDK still relies on charitable donations to maintain them. Most of the German dead were either buried in mass or unmarked graves, or their graves were, after the war, in the hands of Germany’s former enemies. At home, Germany erected numerous local monuments in honour of their war dead, but creating a national day of mourning, with appropriate national rituals and symbols proved impossible in the politically torn Weimar Republic, and that would have devastating consequences for the legitimacy of the Weimar Republic and for German political culture. Today WW1 in Germany is seen as the “Forgotten War”, superseded by the Second World War. Sadly the sacrifices it made between 1914-18, may never be truly known. Whatever their motivation for supporting the war, Germans, like their adversaries, were all individuals, with families, personal hopes and history. Their stories and those of other nations that supported Germany, also need to be remembered.