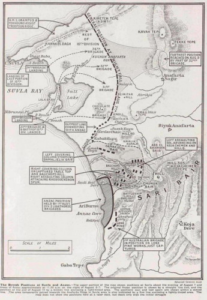

On the 7th August,1915, the Yorkshire regiments landed at Sulva Bay to capture a number of commanding hills. Tekke Teppe Hill above was most prominent and its capture promised a break through to the stalemate at Gallipoli.

On the 7th August,1915, the Yorkshire regiments landed at Sulva Bay to capture a number of commanding hills. Tekke Teppe Hill above was most prominent and its capture promised a break through to the stalemate at Gallipoli.

THE GALLIPOLI CAMPAIGN

Background.

Background.

The Gallipoli Peninsula runs in a south-westerly direction into the Aegean Sea between the Hellesport (now known as the Dardanelles) and the bay of Melas, which today is known as Saros Bay. This strategic waterway has been fought over for centuries, from the days of Xerxes, Alexander the Great and the Roman Empire. By 1915, the Turkish defences of the Dardenelles included forts, with large calibre guns, minefields, shore based torpedo tubes, mobile howitzers and field guns.

At the time of the First World War, this narrow sea strait was a direct route to the Russian Empire, but was controlled by the Turkish Ottoman Empire, allied to Germany. The Allies hoped that capturing the Dardanelles Straits would help supply Russia, defeat Turkey and encourage Greece and Bulgaria to join the allies in the war. It was an imaginative, but poorly executed plan.

The Gallipoli Campaign was originally intended as a Naval battle only. The plan was for a powerful British and French Fleet to sail through the Dardanelles and into the Sea of Marmara, bombard the adjacent Turkish forts into submission and capture the sea route to Constantinople. This over optimistic plan was flawed from the start. To succeed, it was necessary to occupy both sides of the narrows. The 1906, Committee of Imperial Defence had analysed this very scenario and concluded the same. In 1807, rear Admiral, Sir John Duckworth’s fleet experienced untold problems forcing the same waterway. Despite this, on 19th February 1915, twelve capital ships, (four French and eight British), under the command of Vice Admiral, Sackville Hamilton Carden, attacked three Turkish forts, guarding the entrance of the Dardenelles. The bombardment began at 10am at a range of seven miles. The forts were barely visible from this long range and only a few lucky shells hit their target. Poor weather then frustrated the operation and it was not until the 25th February that the bombardment recommenced at a range of 4 miles. On the 26th February and 4th March, sailors and marines landed to survey the destruction of the three outer forts. Sub Lieutenant, Eric Gascoigne Robinson, leading this commando assault was awarded the Victoria Cross for single handedly destroying Turkish naval guns.

Whilst the forts were being bombarded, the minesweepers, mostly requisitioned North Sea trawlers, with civilian crews, were directed up the Dardenelles to sweep for mines. The trawlers worked in pairs, dragging a steel cable underwater, across the minefield. They moved slowly at about 4 knots, hugging the coastline. Against strong currents the trawlers were almost stationary and easy targets for the Turkish shoreline defences. On 13th March they attempted to clear a path under the cover of darkness, but were spotted by Turkish searchlights. Eric Gascoigne Robinson days after his Victoria Cross action, now commanded one of these trawlers and his minesweeper was hit 84 times, by small calibre shells. Four trawlers, two picket boats and the cruiser HMS Amethyst were damaged during this sortie, with 27 sailors killed and 43 wounded. Mine Sweeping continued each night until the 18th March, but the three week effort resulted in only 12 mines destroyed. Without a path though the minefields, the operation was doomed to failure.

As the minefields could not be cleared until the defending Turkish guns had been destroyed, the Anglo-French fleet attempted to force the narrows. On the 18th March, in broad daylight, ten battleships attacked the Turkish shoreline forts, in three waves. The event that really decided the battle took place the night before, when the Ottoman minelayer Nusret laid 28 mines in front of the Kephez minefield, across the head of Eren Köy Bay, a wide bay along the Asian shore just inside the entrance to the straits. As the Allied ships attacking the following day, turned in the narrow straits, they struck these unknown mines, close to shore. The French battleship Bouvet, already damaged, exploded and capsized in just two minutes, killing 643 crew. The British remained unaware of the minefield, thinking the explosion had been caused by a shell or torpedo. Subsequently, two British pre-dreadnoughts, Ocean and Irresistible, were sunk and the battlecruiser Inflexible was damaged by the same minefield. Suffren and Gaulois were both badly damaged by coastal artillery during the engagement. For 118 casualties, the Ottomans had sunk three battleships, severely damaged three others and inflicted 850 Allied casualties. This disastrous day was a major factor in abandoning a naval strategy to take Constantinople. Admiral, Sackville Hamilton Carden had a nervous breakdown shortly after and was replaced by Rear Admiral, Rosslyn Wemyss.

With the failure of the naval assault, the idea that land forces could advance around the backs of the Dardanelles forts and capture Constantinople gained support as an alternative plan. On 25th April, the Gallipoli Campaign commenced, with the allies invading the Gallipoli Peninsular at six beaches. Two landings by the French were successful diversionary attacks and withdrew taking 500 Turkish prisoners. Two British landings at Cape Helles were largely unopposed, but troops failed to move forward and take the high ground quickly. The remaining two landings ay Sulva Bay, were met by stiff Turkish resistance, which confined them to narrow beachheads. At “Z” beach, the Australians rowed ashore in darkness and silence, surprizing the Turks and gaining a foothold. At “W” beach, Cape Helles, the Lancashire Fusiliers attacked in broad daylight, facing heavy machine gun fire and beach entanglements. They lost 700 men and were awarded six Victoria crosses “before Breakfast!”. In hindsight, the Allied landings were poorly executed. They underestimated Turkish resistance and crucially, failed to capture the high ground on the first day. The Allies would never see the other side of the Peninsular or get anywhere near to capturing the Turkish forts. While some Officers advocated immediate withdrawal, General Hamilton ordered troops to dig in. Further landings at Sulva Bay in August 1915, led to a similar stalemate and huge losses on both sides. The Campaign fighting was fierce, attritional and largely static. The first two weeks alone at Gallipoli, saw a higher rate of allied casualties than the Battle of the Somme, when measured as a percentage of those committed.

Forced to dig in around the shorelines, the Allies spent the next eight months trying to capture the high ground and break free from the Peninsular. The heat, then rain and later snow, made trench conditions intolerable. The dead bodies that piled up in the narrow “No Mans” land that separated the trenches, meant both sides suffered from dysentery. Eventually, the Allies were forced to withdraw from Gallipoli on the 9th January 1916. The eight month Gallipoli Campaign was a famous Turkish victory, costly to both sides.

Forced to dig in around the shorelines, the Allies spent the next eight months trying to capture the high ground and break free from the Peninsular. The heat, then rain and later snow, made trench conditions intolerable. The dead bodies that piled up in the narrow “No Mans” land that separated the trenches, meant both sides suffered from dysentery. Eventually, the Allies were forced to withdraw from Gallipoli on the 9th January 1916. The eight month Gallipoli Campaign was a famous Turkish victory, costly to both sides.

The Allied campaign was plagued by ill-defined goals, poor planning, insufficient artillery, inexperienced troops, inaccurate maps and intelligence, overconfidence, inadequate equipment and logistics, and tactical deficiencies at all levels. Geography also proved a significant factor with the Turks holding the higher ground.

Casualty figures vary, but some 140,000 men on both sides were killed during the eight month Gallipoli Campaign. A total of 489,000 Allied troops fought in the Dardanelles, including 50,000 Australians and 17,000 New Zealanders. The Allies lost 141,000 men through disease and 56,707 men killed, included 12,140 ANZAC’s, 31,389 British and 9,000 French. Turkish casualties were estimated to be at least 280,000 with 87,000 killed. Far more British soldiers fought on the Gallipoli peninsula than Australians and New Zealanders put together. The UK lost four or five times as many men in the brutal campaign as its imperial Anzac contingents. The French also lost more men than the Australians.

Gallipoli was a world event. Those buried there, came from Indian villages to the furthest borders of the Ottoman Empire, from Newfoundland and Africa, from the islands of the South Pacific, to the Lancashire mill towns. The last known survivor of Gallipoli was Alec Campbell, who died in his native Australia, in May 2002, aged 103.

The Gallipoli campaign has been keenly debated over the last century. Some believe it was a poorly planned exercise that failed in Whitehall, long before any serviceman set foot on the peninsular. Others argue that the campaign could have been successful, with more resources. Others say it may have made little difference to the main struggle on the Western Front. We can only speculate. However, history has largely overlooked how close the 6th East Yorkshire Regiment, came to winning the campaign, at Tekke Teppe, between the 8th – 9th August 1915. They failed (despite claims otherwise). The following is an interesting and little known episode in the Gallipoli story.

The 6th East Yorkshire Assault on Tekke Teppe Hill 8- 9th August 1915

The campaign in Gallipoli had gone badly wrong since the initial attack in April 1915, when amphibious landings had taken place. Reinforcements for a second major attack were needed and the only troops that were available were the untried Kitchener Divisions. It was against this background that the second landing at Suvla Bay was planned for August 1915. Although the area was only lightly defended, the Suvla landing was no easy operation. The men had received only a few months training and had not been in combat. The junior officers were equally inexperienced with just a few pre-war regulars holding senior positions. An opposed amphibious attack is amongst the most difficult of military operations, and the use of inexperienced troops for this, was with hindsight, highly ambitious. The 6th East Yorkshires landed near Lala Baba, at Suvla Bay, on the 7th of August. Their objective was to capture Tekke Teppe, a hill about 800 feet in height, in the centre of a series of ridges disposed, roughly in the shape of a horseshoe and enclosing Suvla Bay. General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, maintained that capturing this hill was crucial to succeed at Gallipoli.

The 6th East Yorkshire Battalion landed at Gallipoli in the early hours of the 7th August 1915, with 22 Officers and 750 other ranks. (Three Officers and 153 men had been left in reserve at Imbros). They were confronted by blazing hot, sunlight, and then freezing, pitch darkness at night. The landscape was a wilderness of tangled, prickly scrub, precipitous rock and innumerable gullies. The craggy earth rotted to the tread and sandy soil made digging in difficult. Hidden within the long grasses, were peculiar snakes, scorpions, centipedes and an a range of other insects, that would bite and sting. One can only imagine what these new troops felt, as they hauled their forty pound packs, with picks, shovels, 200 rounds of ammunition and water to the foothills of Tekke Teppe.

While the landing was not opposed, the assault on the hill was. The Turkish defenders, although few in number, were able to inflict heavy casualties amongst the Yorkshiremen. The junior officers, leading from the front, took disproportionately heavy casualties. Fatalities amounted to eleven officers and 56 ‘other ranks’ in the 6th Yorkshires and six officers and 25 ‘other ranks’ in the 9th West Yorkshires, on the 7th August.

Over the next two days, the troops, fought in sweltering heat, by day and in freezing darkness by night, without rest, and with little food or water. The landscape was hostile and offered little cover from snipers and shelling. There were few landmarks to co ordinate attacks. Hot shells ignited the dry scrub, setting the hills afire. Many stranded wounded, were burnt alive in these bush fires. A choking haze then filled the air, creating an unquenchable thirst. Fighting was attritional, full of pain, blood, sweat, and wasted gallantry. Casualties mounted as food, ammunition and precious water, had to be dragged miles inland, up narrow, winding gullies, targeted by snipers and shellfire. Within days the battlefield was cloaked with the stench of death, and plagued by insects. Unable to wash, soldiers were tormented by lice, dirt and flies and soon the scourge of dysentery set in .

The 6th (Pioneer) East Yorkshire attack on Tekke Tepe, is vividly recorded in their War Diary, which is with the 11th Divisional Diaries. (This diary is easy to miss, as it is not part of the line Battalion War Diary bundles. It is included in the Division papers, as the Pioneers were technically Divisional troops, although it seems they were attached to the 32nd Brigade for this operation).

Capt. V. Kidd, Adjutant of the 8th Battalion Duke of Wellington‘s Regiment (West Ridings), also recorded the event in his personal account, which is an appendix to the 8th Battalion War Diary notes. Also the 6th Battalion, York & Lancs, War Diary, records the Turks’ attack over Tekke Tepe.

This is the 6th Battalion EYR, War Diary:

8th Aug 1915. Orders were received to join the 32nd Brigade with the WEST YORKS on our left, to attack and hold a position running from CHOCOLATE HILL to SULAJIK 105 C 6. The records of these orders have been lost. The Battalion advanced B [Coy] on the left under Major, BRAY, D [Coy] on the right under Captain GRANT, C [Coy] in second line and A [Coy] in reserve. Lt Col, MOORE advanced with the 1st line. At first no opposition was met with, but occupying the ridge which joins up with CHOCOLATE HILL and was about W by S from ANAFARTA SAGIR heavy firing was encountered. (Margin: Ref to ANAFARTA SAGIR sheet 1:20,000 Gallipoli Map 105 C 6)

Captain ROGERS was killed and shortly afterwards Major, ESTRIDGE was wounded in the arm. The Turks employed numerous snipers and shot particularly at our men as they went for water at a well. Parties were sent out, but were unable to find them. The position was entrenched on the reverse slope during the day and further forward during the night. Two officer’s patrols were sent out during the evening: At about 11:30 pm orders were received for the Battalion to retire to the points held by the WEST RIDING Regt and to occupy and improve a Turkish trench there. 11:30 pm. The orders have been lost. The men were tired and exhausted and short of water moving often in the dark led to equipment being mislaid.

9th Aug 1915. We found the West Riding Regiment in a vacant Turkish Trench at about 1:30 am. After some confusion getting the men into the trench in the dark, orders (lost) were received at 3:30 a.m. (late in reaching us) to deliver an attack (orders lost) on TEKKE TEPE (Sheet 119 O2) the West Riding Regt was to attack KAVALA TEPE (Sheet 119 C7) on our left. The men were at this stage in a state of extreme exhaustion and hunger. The Battalion moved northwards out of the trench in the following order D, C, B, A after passing SULAJIK we took a NE route crossing the dry beds of the streams.

Verbal orders had been given by Lt Col Moore that in the attack D and B Companies should form the first line (D on the left, B on the right) A Coy (Capt WILLATS) the second line and C Coy (now under Capt, PRINGLE) the reserve. Lt Col, MOORE was with D Coy. The other three companies due to the extreme exhaustion of the men and absence of explicit orders failed to keep in touch with D Coy who proceeded to advance up the lower slopes of the hill without waiting for B Coy to come into position on their right or for the other two companies to get into place. D Coy with Lt Col MOORE and 2 Lt STILL (Acting Adjutant) and HQ party seemed to have encountered no opposition at first.

It was only when they were up the first shoulder (Sheet 119 L4) that the strength of the enemy was disclosed. Fire was poured in from concealed Turkish trenches and our men were unable to hold their ground. There was considerable confusion due to the rapid advance of D Coy and the fact that the other Companies had lost touch. D Coy suffered heavily. Capt GRANT had been wounded in the hand early in the engagement – Lt Col, MOORE, 2 Lt STILL, Capt, ELLIOTT, Lt, RAWSTORNE, 2 Lt, WILSON were all missing when what remained of the Coy fell back. A general retirement took place during which there was much mixing of units due to the Battalion failing to keep its formation. After two other stands had been made in conjunction with the West Riding Regt a line was eventually taken up along a line running N from (Sheet 118 V6). Reinforcements came up here and about 13:00 the Battalion was relieved and ordered to concentrate at the cut on A Beach (Sheet 104 B1).

All orders and dispatches relating to these are lost as the orderly who carried them is missing……[A long list of Officer casualties follows] Other Ranks: Killed 20, Wounded 104, Wounded and Missing 28, Missing 183.This night the battalion bivouacked on ‘A’ Beach near the cut.”

The withdrawal of the East Yorkshires of the night of 8th August was difficult. There was no moon and it was pitch dark. It was almost impossible to find equipment and assemble the battalion quickly to move off to Sulajik. All the time, the Turks continued their fire on the East Yorkshire, while they moved back and reached the position in the early hours. The East Yorkshire soldiers on arrival at 1.30am, dropped with exhaustion. Between 3 and 3.30am, all Company Commanders were suddenly ordered to report to the Colonel. They were told that the 6th East Yorkshire Regiment had received orders to seize the very high hill above Anafarta (Tekke Tepe).

The West Ridings would attack another hill on the left (Kavak Tepe). As the orders had arrived late, the battalion had to move off immediately. The men in a state of exhaustion, thirsty and hungry had to be pulled out of their trenches. Colonel HGA Moore started off with HQ and D companies. When the three remaining companies assembled they found Colonel Moore, their Commanding Officer had gone ahead. In crossing the open space between the trenches at Sulajik and the foot of the hill, little or no opposition was encountered. Two officers of the 67th Field Company Royal Engineers, Major, F.W. Brunner and Lt. V.Z. Ferranti accompanied Lt Col. Moore. Lt Ferranti was ordered to wait and follow up with the next company of East Yorkshires that came along. The group split into three parties Col Moore., Maj. Brunner and 2/Lt Still, with one party, Capt. Steel with another and Capt. Elliott with the third. As they reached the lower slopes of the hill north of Baka Baba, the rifle fire from the snipers became more insistent. They carried on up Tekke Tepe, the casualties becoming more serious. Major Brunner was killed and many others shot down. The survivors, Col. Moore and 2nd Lt. Still leading, reached the summit along with Capt., Elliot, Lt, Rawstone and between 12 and 30 men. They were cut off by the advancing Turks and the survivors, five in number, including Mr. Still, were captured.

This little party of East Yorkshire men and Engineers achieved the brilliant feat of reaching a position, farther east on the heights above Suvla Bay than any other troops in the entire campaign. Of the 750 men in the 6th (Pioneer) East Yorkshire Battalion, 347, or roughly 46% had become casualties in just 3 days. Officer casualties were 15, or 75% of those who landed on 7th August. They included two Officers killed in action; five wounded; six ‘Missing in Action’ and two ‘Wounded and Missing’. Most of those ‘Missing in Action’ at Gallipoli were actually killed. They included career soldier, Lt Col Edward Chapman, who had served in the Yorkshire Regiment since 1895 and had raised the 6th East Yorkshire Pioneers, at Ripon in August 1914. The Chaplain wrote to his father, ““He died as he would have wished to die – a gallant soldier leading his men, himself at the very front of the Regiment on the summit of Lala Baba……despite the hail of bullets and the shower of shrapnel which had now got the range, the Yorkshires pushed forward to the Turkish trenches on the crest of the hill. There it was that the colonel’s gifts of leadership made themselves felt. ‘Come on the Yorkshires’ he cried, and at their head with fixed bayonets, the lads he trained so well swept forward with irresistible force and the hill was ours”. His cousin, Captain, Wilfrid Hubert Chapman, of the 6th Yorkshires, was killed in the same attack, aged 35. Another killed was Captain, Robert Randerson, an outstanding sportsman, who had played for the Batley (Northern Union) football club. A teacher at St Mary’s Roman Catholic School, Batley, Randerson was commissioned shortly after the outbreak of war and gazetted captain about two months prior to his death, aged only 24. Searching this website shows that 47 men, killed with the 6th East Yorkshires came from Hull, and ten others died on the 9th August 1915 at Suvla Bay, fighting for New Zealand, the West Ridings and other regiments.

After the War, all captured British Officers were required to make a written statement to the War Office, about the events surrounding their capture. Captain R D Elliott, 6th Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment captured at Tekke Tepe recounted how they reached the top of hill. Another account by Lieutenant, John Still wrote. “About thirty of us reached the top of hill, perhaps a few more. And when there were about twenty left we turned and went down again. We had reached the highest point and furthest point that British forces from Suvla Bay were destined to reach. But we naturally knew nothing of that.

General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, wrote in his War Diary, that Tekke Tepe was the

key hill, overlooking Suvla Bay. He believed British troops had actually reached the summit of the hill on the 9th August, and that, had they been given proper support, victory was in sight. However, until 1923, he had no definite evidence to confirm his belief. In October 1923, he received a letter printed in The Times, (on 30th October 1923), from Mr. John Still, a tea planter in Ceylon, who had been adjutant of the 6th Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment, a unit of the 32nd Brigade, during the Suvla operations. He gave details of his own experiences on Tekke Tepe as follows:-.

“I was the only officer on that hill who had spent years in jungle and on hills and was in consequence able to appreciate things accurately. We had been ordered to take up that position on the map and we took it up. I fixed our exact position by prismatic compass. We fought all day there and had a good few casualties including two officers (or three), and then we were taken off again at night “because the regiments to right and left of you have not been able to get up”. That was the night of August 8. On our right were a Sergeant and two men only of another regiment, lost and re-found by us. I forget their unit, but I can still see the identifying mark on their backs in my mind’s eye: it was a sort of castle in yellow. Beyond them there was a gap right away to Chocolate Hill. On our left was not as you state another regiment, but only a weak half company of the West Yorkshires with two officers of whom one was killed, and the other – Davenport– severely wounded. And this left us in the air. Your orders given to General Stopford at 6pm never reached us on Scimitar Hill. Why? They knew where we were, for I was in touch by day with Brigade H.Q. signallers on Hill 10 or close to it. By night I lost contact for both my lamps failed me. As you justly say, anyone with half an eye could see Tekke Tepe was the key to the whole position. Even I, a middle-aged amateur who had done a bit of big game shooting and knocking about saw it at once. We reconnoitred it, sent an officer and my signaller corporal to climb it, and got through to Brigade H.Q. the message giving our results. I sent it myself. The hill was then empty. Next morning you saw or heard that troops had actually reached the top of Tekke Tepe. Yes they had. A worn and weak company, D Company, of my regiment, together with my Colonel (Moore). Major Brunner, of the Royal Engineers., and myself started up that hill. About thirty got to the top: of them five got down again to the bottom, and of those three lived to the end of the war. I was one of them. You wonder why we did not ‘dig in’ (pages 78 and 79 of your Volume II) as we had lots of time. There, Sir is where that war was lost. You sent a Brigade at that empty hill on the afternoon of the 8th. Actually, owing to staff work being so bad, only a battalion received orders to attack, and they did not receive those orders until dawn on the 9th.

I received them myself as adjutant. The order ran to this effect: “The C.-in-C. considers this operation essential to the success of the whole campaign”.  The order was sent out on the late afternoon of the 8th, when we were on Scimitar Hill. It reached us at dawn on the 9th in a Turkish trench at Sulejik. In the meanwhile, for those hours more precious to the world than we even yet can judge, the Brigade Major was lost! Good God why didn’t they send a man who knew the country? He was lost, lost, lost and it drives one almost mad to think of it. Excuse Me. Next morning (from the order) at dawn on the 9th you saw some of our fellows climbing cattle tracks. You don’t place them exactly where I think you really saw them, but as I know, there were none just precisely where you say you saw them, I am pretty certain it was us you saw from the ship, only we were half a mile north of where you describe. Then we climbed Tekke Tepe. Simultaneously the Turks attacked through the gap from Anafarta. Their attack cut in behind D Company and held back the rest of the battalion who fought in the trench, with the Duke of Wellington‘s on their left. We went on, and, as I said, not one of us got back again. A few were taken prisoner. I was slightly wounded, and stayed three years and three months as a prisoner. Later that morning we who survived were again taken up Tekke Tepe by its northern ravine on the west side. Turkish troops were simply pouring down it and the other ravines. On the top of Tekke Tepe were four field guns camouflaged with boughs of scrub oak, and a Brigade H.Q. was just behind the ridge. I had a few minutes conversation there with the Turkish Brigadier in French. But I am coming home on leave in March or April next.

The order was sent out on the late afternoon of the 8th, when we were on Scimitar Hill. It reached us at dawn on the 9th in a Turkish trench at Sulejik. In the meanwhile, for those hours more precious to the world than we even yet can judge, the Brigade Major was lost! Good God why didn’t they send a man who knew the country? He was lost, lost, lost and it drives one almost mad to think of it. Excuse Me. Next morning (from the order) at dawn on the 9th you saw some of our fellows climbing cattle tracks. You don’t place them exactly where I think you really saw them, but as I know, there were none just precisely where you say you saw them, I am pretty certain it was us you saw from the ship, only we were half a mile north of where you describe. Then we climbed Tekke Tepe. Simultaneously the Turks attacked through the gap from Anafarta. Their attack cut in behind D Company and held back the rest of the battalion who fought in the trench, with the Duke of Wellington‘s on their left. We went on, and, as I said, not one of us got back again. A few were taken prisoner. I was slightly wounded, and stayed three years and three months as a prisoner. Later that morning we who survived were again taken up Tekke Tepe by its northern ravine on the west side. Turkish troops were simply pouring down it and the other ravines. On the top of Tekke Tepe were four field guns camouflaged with boughs of scrub oak, and a Brigade H.Q. was just behind the ridge. I had a few minutes conversation there with the Turkish Brigadier in French. But I am coming home on leave in March or April next.  May I have the honour of meeting you and going over it on the map? I think much might be cleared up that was still obscure when you wrote your book. There are one or two things one prefers not to write. Please let me know your wishes in this matter. I loved your book and I want to do any small thing possible to complete your picture. Yours truly (Signed) JOHN STILL, Victoria Commemoration Buildings, Nos: 40 and 41 Ward Street, Kandy, Ceylon Sept 19.

May I have the honour of meeting you and going over it on the map? I think much might be cleared up that was still obscure when you wrote your book. There are one or two things one prefers not to write. Please let me know your wishes in this matter. I loved your book and I want to do any small thing possible to complete your picture. Yours truly (Signed) JOHN STILL, Victoria Commemoration Buildings, Nos: 40 and 41 Ward Street, Kandy, Ceylon Sept 19.

Second Lieutenant, James Theodore Underhill, was a 22 year old, adjutant serving with the 6th East Yorkshire Battalion at Galipolli and was the Signaller at Tekke Tepe. His letter to the Times, published 14thFebruary 1925, recounts the following”….Being a qualified land surveyor, and experienced in the use and construction of maps and the knowledge of the country, I was well able to keep notes of our positions and was the officer mentioned in your letter who took the patrol up Tekke Tepe. In fact I still have your signal corporal’s field glasses which I took from him while on the hill, my own being smashed by a rifle bullet whilst using them on this patrol. My report disagrees with your letter in a few minor details – for instance while on Scimitar Hill, the 9th West Yorkshires were on our left, as I was actually speaking with their officers on their own right flank, but they were withdrawn before us, God knows why. Again, while you say Tekke Tepe was not occupied, it was held very lightly by patrols. We ran into two of them before reaching the top; out of one we bagged two Turks, the other escaped us. There were also three short lengths of partially dug trenches unoccupied while we were there, but showing signs of most recent occupation. Further, you say that the Turks came in behind D Company and the rest of the battalion fought in the trench.

This is not quite right. We had advance fully 1500 yards (and I was with the rear company “B”) before we encountered the Turks. When we did, it was a ‘free for all’ bayonet affair, with the Turks outnumbering us about three to one. I saw nothing of the West Yorkshires as you mention, but the West Ridings who were to have supported the Brigade!!! attack were present. However, my report and your letter agree in the great fundamental point, this, that Tekke Tepe should have been taken on the evening of August 8. That this could and would have been done had there not been a lamentable failure of the Staff, I think goes unquestioned by those of us who had an accurate knowledge of the conditions; it was the loss of the Gallipoli campaign. I am even of the opinion that, that had the Staff work not been so rotten, and that had the attack in the early morning of August 9 been by three battalions instead of us alone, it might have been successful. If you remember, the attack was to have been a brigade affair, three battalions in attack with one in support. The supports (the West Ridings) were there, but where the other two battalions were, God alone knows. I think all of Kitchener’s Army who took part in this landing and the following few days felt it intensely that they were blamed by the Staff for the failure on the grounds of being green troops. Compared with later experiences in France, the 11thand 10thDivision fought as well as any troops ever did, be they Regulars or otherwise, and I am sure that those of us who had the honour to belong to either the 11thor 10thDivisions feel grateful to you for coming out plainly and placing the blame where it so justly belongs.”

In 1928, some years after Lt Still’s and 2/Lt Underhill’s letters to the newspapers published in 1923 and 1925, Everard Wyrall published “The East Yorkshire Regiment in the Great War”. This ignited the debate surrounding the East Yorkshires capturing Tekke Tepe. Wyrall’s History states that three patrols sent out by the 6th Bn East Yorks on the 8th August reached various key positions. It also gives grid references, one of which exactly tallies with Tekke Tepe, “Top of Tekke Tepe” and “Anafarta Ridge”. There are other first hand accounts , including, Major, Cowper, Second in command, (Quoted in detail and also in correspondence with Aspinall Oglander); Maj Bray OC B Coy. Quoted in detail; Capt Still Acting Adjt (additional info) Partly quoted and Lt Ferranti RE, 67th Field Coy RE. The leading company (D Coy) split into three groups led by Lt Col Moore CO, Maj Brunner RE and Lt Still, 2) Capt Steele and 3) Capt Elliott.

The CO, Capt Elliott, Lt Rawstone and Lt, Sill reached the summit. Various accounts put the numbers reaching the summit between 12 and 30 men The history describes it thus: “This little party of East Yorkshiremen had achieved the brilliant feat of reaching a position father east on the heights above Suvla Bay than any other British troops….” It goes on to describe how they were surrounded at the top and how Lt Col Moore was killed at the top.

In 1934, the debate continued, when Lt Colonel, A Kearsey, General staff, who served in the Dardenelles, published his “Notes and Comments on the Dardanelles Campaign”. On page 63, he states “[on the 9th August] A company of the East Yorks attached to the 32nd Bde succeeded in occupying a position on Tekke Tepe, commanding the whole of the Anafarta Sagir“. Unfortunately, he provides no evidence to support this claim. He also says that the 32nd Bde withdrew…but does not specifically mention the East Yorkshires again and gives no timings for the withdrawal.

Some argue that the 6th East Yorkshire attack on Tekke Tepe (actually in effect only D Coy and Battalion HQ) never reached the summit on the 9th August 1915. Also the Officers were mistaken when they said that they reached the summit, or had made it up after the war to compensate for being taken Prisoner. As most of the East Yorkshires, were killed or captured, all the official reports were compiled after the events, by persons who had not been present. The War diaries show very clearly that patrols sent by the 6th East Yorkshires on the 8th August (the day before) met with little opposition, but a later advance on the 9th August to exploit this opportunity by the 6th East Yorkshires, supported by the 8th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding) and 67 Coy Royal Engineers was too late. It was repulsed by Turkish reinforcements, with heavy loss to D Coy of the 6th East Yorkshires, who advanced without waiting for the remainder of the Battalion. However, the primary sources of Lieutenants John Still and James Underhill, who both were there at the time, claim that they did occupy Tekke Tepe. John Still was a 35 year old, tea planter, use to the hills of Ceylon and Underhill, was a newly qualified land surveyor, aged 22. Both would have known if they had reached the top of Tekke Tepe. There was no collusion between these two men to make up their story. Lt., Still was captured and spent the rest of the war in Turkey. He believed he had been the only surviving Officer in the attack. Underhill although wounded in the chest, survived the war and then emigrated to Vancouver. If they did occupy Tekke Teppe, it would have been the furthest allied advance on the Peninsula, and if they had held this strategic position, the Gallipoli Campaign would have succeeded.

After 100 years we can only speculate. It is perhaps best to concentrate on the bravery of the 6th (Pioneer) East Yorkshire Regiment, who stormed the hill with limited support in difficult conditions. These Pioneers were used in (arguably) the most important assault of the campaign. They were ably led, by Col Moore, (who had risen from the ranks) and were decimated within sight of their ultimate objective. Their attack was undermined by appalling planning and procrastination. There was no time for orders or battle preparation. It was a fragmented, uncoordinated attack, characterised by perhaps over-zealous leadership, tactical naivety, exhaustion and fatigue. (The men had to be kicked into action, from a state of near exhaustion). This superhuman effort resulted in failure, then denial and blame. The 6th East Yorkshires who had landed at Gallipoli in the early hours of the 7th August 1915, with 22 Officers and 750 Other ranks, had within 3 days, lost 15 Officers and 347 other ranks. The Turks reported forty four, 6th EYR prisoners and nine from other regiments, were captured during the engagement. Some of these died later in captivity. Repatriated prisoners after the war, also reported that some prisoners were executed at the time. They included Colonel Moore, who was bayonetted, on top of the hill having surrendered.

Over 50 men from Hull died in Gallipoli on the 9th August 1915. The story of the 6th East Yorkshire at Tekke Tepe, is not a particularly well researched, or well understood part of the campaign, outside a few specialists, but it encapsulates everything in one small action that was wrong about Gallipoli.

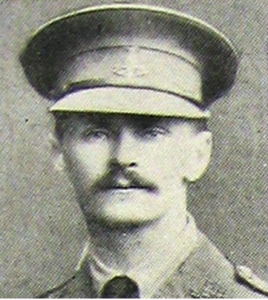

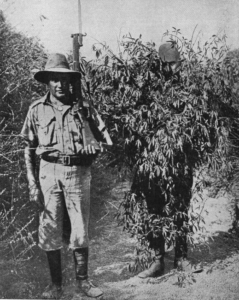

Below are pictures of Officers of the 6th East Yorkshire, before disembarking to the Dardenelles. Of the 30 Officers, only 3 survived the landings intact, 16 were killed and 11 wounded. The second picture is of “A” Company of the 6th Battalion before Gallipoli. The third picture is of a unknown company of the 6th EYR, also before leaving England in 1915.

The following recounts the progress of the 6Th East Yorkshires, after the Tekke Tepe attack.

21st August 1915 – the attack on Scimitar Hill

Wyrall’s “East Yorkshire Regiment in the Great War” shows that the 6th East Yorkshire Regiment had been in reserve from 10th to the 20th August at Nibrunesi Point where they had dug themselves in at the base of a cliff. On 20th August, the 6thEast Yorkshires relieved the Northumberland Fusiliers in trenches South East of Chocolate Hill. They came under the orders of 34th Brigade who would attack “Hill W” the next morning.

The 6th Battalion were to dig in and support the Lancashire Fusiliers and the Dorset’s, who would attack the next morning. There was a delay due to lost orders and confusion, and the attack did not commence until 3pm on the 21st. When the Dorset’s and Lancashire’s left their trenches the 6th East Yorkshires moved forward to occupy these trenches. The Dorset’s and the Lancashire’s ran into stubborn resistance and so most of the 6th East Yorkshires were sent forward to support them. The 6th East Yorkshire‘s captured a Turkish trench in front of them and awaited relief. The 6th East York (Pioneers) had occupied Hill 70 (Scimitar Hill), next to W Hill the most vital of all the semicircle of heights overlooking Suvla Bay and were there only waiting for the brigade’s further advance upon W Hill or Anafarta Sagir, to both of which it is the key. They held this trench overnight, but it became impossible to hold the next morning (22nd August) as the number of Turks increased and they had no bombs. Around 7.30 am the 6th East Yorkshires retreated to their original trenches and later that night they were relieved and moved back to their original reserve trenches at Nibrunesi point the following morning. The 6th East Yorkshire casualties by 22nd August 1915, included 26 Officers and 628 men. Officer casualties were 80% and other ranks 68%. They included Captain, Arthur “Jimmy” Dingle, 6th EYR killed on 22nd August 1915, aged 23. He had played Centre for England and Rosslyn Park, Rugby Football Club.

20th October 1915

The War Diary for the 6th (Service) Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment (Pioneers) on 20th Oct 1915 is edited below. It was written in very feint pencil and just legible. The Battalion was scattered over a place known to the troops as ‘Piccadilly Circus’ or ‘Shrapnel Valley’ due to heavy Turkish shelling. There are no records of battle casualties, but the War Diary contains long lists of men admitted to hospital and lists of men who arrived in drafts. Notably most posted to D Coy – a stark reminder that D Coy was virtually wiped out on the lower slopes of Tekke Tepe on 9th August.

“Working Parties A Coy Piccadilly Circus, Div Head Quarters ^ well [illegible – above?] XI Signal Depot, Field Ambulance dugouts. B Coy 9th A.C [Army Corps] New Head Quarters, Park Lane, Holborn, Jephson’s Post Road (Oxford St). D Coy 9th A.C Head Quarters, 67th Coy RE – SW Mounted Brigade dugouts, Cannon Street. Two general road repairing parties under 2/Lieuts SIEBER and SCOTCHER. 2/Lieut HICKEY was wounded in the arm by shrapnel bullet whilst working near Piccadilly Circus & admitted into 35th Field Ambulance.”

Gallipoli 100 Years on – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-32456487

The Consequences of Gallipoli

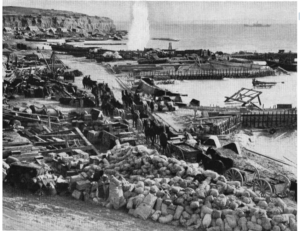

The British government ordered the evacuation from Suvla Bay on the 7th December 1915. Unlike the Campaign, the evacuation was a remarkable success – a brilliant piece of organisation, in which soldiers and sailors, worked together with the upmost skill and courage. The evacuation of Anzac started on 15th December. Over 5 nights at Anzac, 3,500 soldiers, 3,600 horses and mules, 130 guns, 330 vehicles and over 1,500 tonnes of equipment were silently withdrawn to the waiting transport ships. The last troops left Helles, on the 9th January, 1916. Over 83,000 troops, and transports were evacuated, with the loss of one life. Various tricks, like the “Drip rifle”, were employed to convey trenches were occupied. Other stunts, included irregular artillery barrages to feign an attack and keep the Turks occupied. Even a cricket match was staged at Shell Green, two days before departure, to convey all was normal. In the final hours, a few hundred “Die Hards” held the frontline trenches against 170,000 Turks. These hand picked Officers and men were athletes, given meticulous instructions to set off rifles, blow tunnels, lay mines and booby traps. To a set timetable, they silently stole away to safety, in single file, along specific routes, marked by white washed sandbags. Indian Mule handlers, used great skill in dampening surfaces and keeping movements as quiet as possible. These were tough, tense, anxious times, expecting the Turks to discover the ruse at any moment. On the beaches, vast quantities of abandoned stores were prepared for destruction. Supplies were poisoned, equipment sabotaged, and sadly, horses shot. At 4.10am on 6th January, tightly packed boats, left the beaches. HMS Cornwallis, the last battleship to leave, shelled the Turkish trenches as it sailed away. The Turks who believed that they were about to be attacked, were completely deceived by the evacuation. Over the coming days, Turks nervously penetrated the abandoned Allied trenches. They found a wasteland of debris and obstacles. It took the Turks nearly two years, to clear the Peninsular of mines, at great loss of life.

In all, some 490,000 Allied forces took part in the Gallipoli Campaign, at a cost of more than 250,000 casualties, including some 56,000 dead. On the Turkish side, the campaign also cost an estimated 250,000 casualties, with 65,000 – 87,000 killed. Gallipoli is often overshadowed by the losses on the Western Front, but it is best remembered for forging the National identity of Australia and New Zealand, whose forces suffered disproportionately. The hard lessons learned at Gallipoli would be used to plan the amphibious attacks in the Second World war at Sicily and Normandy. Even today, the United States Marine Corp pioneer new landing craft and tactics inspired by the Gallipoli campaign.

Britain failed all of their initial objectives. They were unable to supply Russia, leading to Russia’s embarrassment on the front that the Turks were bombarding. Russian civilians protesting against the conditions in which they were expected to live, forced their Tsar to abdicate in 1917. The Ottoman Empire remained a combatant until 1918, and were joined by Bulgaria shortly after the failed landing on the 25th April 1915.

Although their confidence was bolstered, the Gallipoli campaign weakened the Turk’s physical forces, to an extent that made them significantly easier to defeat, simultaneously allowing the British navy to bypass the underwater minefields that the Turks had planted in the Dardanelles that had originally caused them great trouble. Thus, they could then destroy the Turkish fleet. The result of this war, was the collapse of the Ottoman Empire’s and transition into the Republic of Turkey, the name by which it has been officially known since 1923.

The failure of the Gallipoli campaign meant that the war had to now be fought through the Middle East, starting at Egypt, then through Palestine, Syria and Lebanon. This conflict was to drag on a further three years with the fall of Constantinople in 1918.

Winston Churchill who supported the Gallipoli plan, lost his job as First Sea Lord of the Admiralty. Sir Ian Hamilton who conducted the campaign was recalled and never saw military action again. Herbert Asquith, the Liberal Prime Minister was forced to resign and a new coalition Government was created in Britain. Under the leadership of Lloyd George, Britain was put on a war footing which was more focused on winning the war. Strikes were banned, food was rationed and women were integrated into the national workforce for the first time. This experience would change social attitudes and begin the modern Britain that we recognise today.

The Gallipoli Campaign taught the military world extremely important lessons about combat and the lesson learnt inspired the more successful D Day landings in the Second World War. British Commanders also learnt the value of Commonwealth troops, and their sacrifice at Gallipoli, helped define a new National identity for Australia and New Zealand.

Links The Gallipoli Campaign http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallipoli_Campaign

8 things about Gallipoli http://www.history.com/news/8-things-you-may-not-know-about-the-gallipoli-campaign?cmpid=Social_FBPAGE_HISTORY_20150425_172975093&linkId=13760087

Gallipoli 100 Years on – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-32456487

* (I am grateful to Edward Underhill who supplied the above information on his grandfather – 2nd Lt., James Theodore Underhill, who was born in Moseley, Staffordshire, 1892. His family emigrated to Canada in 1894 and he obtained his Land Surveyor’s qualification at McGill University (West) which was later to become the University of British Columbia. Upon the outbreak of the war, he gained his qualification as an Infantry Officer in January of 1915 at the Provisional School of Infantry in Vancouver, BC and subsequently travelled to England, having missed the opportunity to join the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). He was commissioned in March of 1915, joining the 6th (Service ) Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, as 2nd Lieutenant by the time of the actions around Teke Tepe. He was shot in the chest during the Gallipoli attack and wounded again in the right knee on 1st July 1916, at Serre, serving with the 12th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. He later served with the Canadian 245th Siege Battery RGA. He lost two brothers in the war and returned to Vancouver, Canada after the war)