Cenotaphs memorialise nearly a million British soldiers who died in the First World war, but more than twice that number were wounded, and these are less remembered.

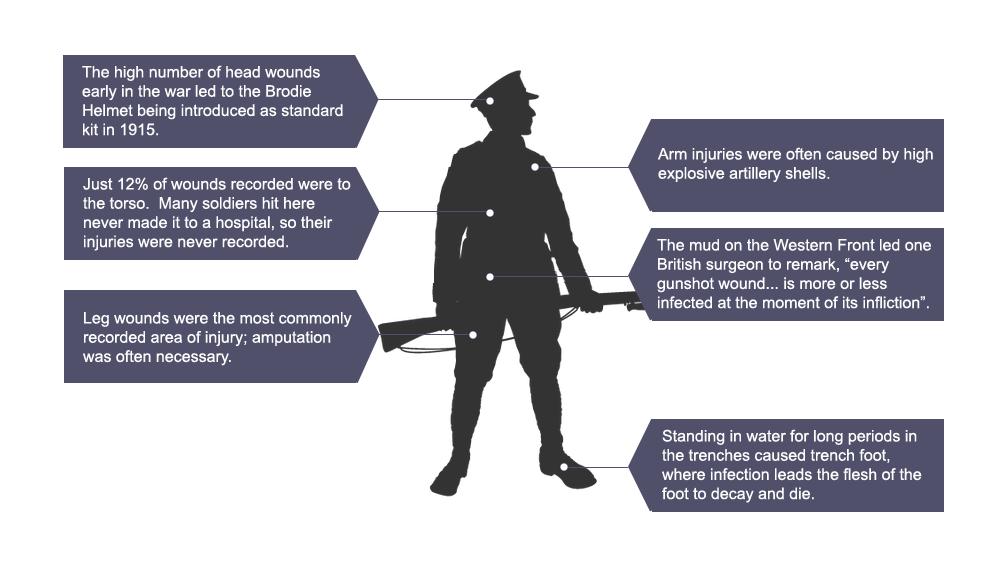

By 1918, the number of Army servicemen wounded during the war totalled 2,272,998 (this figure counting those who were wounded more than once), 64% of whom returned to duty, and 18% who returned to non- battle services. Eight percent were discharged as invalids. Around two million British war wounded had sustained permanent, life-changing injuries from disease and modern warfare. About 60% of these wounds were caused by artillery. A British soldier was three times more likely to die form a shell than a bullet wound. The level of disability included: amputees; some had facial disfigurement or were blinded, others suffered from deafness, lung damage caused by poison gas. There were thousands of cases of shell shock and damage from the horrors of warfare, diagnosed today as post-traumatic stress disorder. In addition, large numbers contracted tuberculosis (TB) in the trenches, a disease which could not then be permanently cured, but only slowed down through careful long-term treatment. A recent analysis of War Pension records, show that malaria, bronchitis, rheumatism and heart problems were also prominent medical conditions for those discharged after the war.

By October 1922, the Ministry of Pensions was paying 900,000 pensions to disabled ex servicemen. These wounded included 80,000 gas victims, 30,000 made deaf, 80,000 with “Shell Shock” and some 250,000 amputees. The number of wounded increased over time. By the end of 1928, nearly 2.8 million war veterans received a disability pension of some sort. 495,545 were supplied with an artificial limb, mobility aid or other surgical appliance.

The First World War introduced new terror weapons, such as planes, tanks, poison gas, flamethrowers, and high explosive shells. With these horrors came new types of wounds. Powerful rifles and machine guns, which fired tapered bullets, hit fast and hard, taking bits of dirty uniform and airborne soil particles with them, as they ricocheted off bones and ploughed through soft flesh. Shrapnel fragments from shells, created jagged wounds that didn’t stop bleeding and which, if the casualty survived the initial impact, provided the perfect environment for infection and sepsis.

Poisonous Mustard gas, would cover the victim in a ghastly smell, causing blindness, burning eyes and throat, swelling up of the body and difficulty with breathing. All this would happen, as the victim would slowly be dying a painful death. The use of other gases, such as Chlorine and Phosgene, caused similar side effects and had their own medical challenges.

“Shell shock” was probably the most tragic illness in World War 1. It was the condition that left World War One troops blind, deaf, mute and paralysed after the trauma of the trenches. The term was coined in 1915 by medical officer Charles Myers. At the time it was believed to result from a physical injury to the nervous system during a heavy bombardment or shell attack, later it became evident that men who had not been exposed directly to such fire were just as traumatised. This was a new illness that had never been seen before on this scale. The condition was poorly understood medically and psychologically. Today, the condition is known as post-traumatic stress disorder and the treatment and attitude to it are very different. “Shell Shock” affected both the soldier’s mind and performance. Survivors could sometimes not recognize their families or communicate with them properly. With no known cure, victims were often committed to asylums for the insane. The UK Government awarded a total of 84,700 war pensions for shell and other neuropsychiatric illnesses. An extrapolation from the official medical history of the Great War suggests that 325,300 servicemen were treated for neuropsychiatric illnesses during the conflict. Studies of shell shock in the French and German armies, suggest perhaps 200,000 UK men suffered from ‘shell shock’ as result of the First World War.

The battlefield conditions of WW1, also created perfect habitats for diseases, like Typhoid, as dead bodies were washed into water ways which soldiers drank from. In extreme cases, typhoid led to death, but mostly, it led to a prolonged sickness – fever, sweating, headache, abdominal pains, diarrhoea or constipation, lack of appetite and weight loss along with vomiting. Exposure to dead bodies, unclean water, cigarette smoke, fuel and gunpowder, noise, along with all kinds of weather, from sunburn to hypothermia weakened the human body and spirit.

Another new infection was “Trench Fever“. This was a body lice which carried disease and was passed on between soldiers, sometimes more than once. The Fever was very unpleasant and took about 12 weeks to heal. Symptoms included high fever, headaches, aching muscles and sores on the skin.

“Trench Foot” was another war condition, caused by soldiers having their feet exposed in water and mud for long periods. This cut off the circulation of blood from the foot, and could eventually lead to the foot being amputated and severe pain.

For those wounded men, who made it back home, the war never really ended. Many spent years in hospital, and were in pain for the rest of his life. They often returned home to poor housing and insanitary living conditions. There was no National Health Service and little welfare provision. The wounded and their families had to learn how to cope. Letters, written by widows, mothers and sisters of men in the Great War, reveal an age when self-sacrifice and stoicism were the norm.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-4186482/Letters-written-widows-men-killed-Great-War.html

How World War I Revolutionized Medicine

Many medical techniques used today have their origins in World War One. The War developed; X Rays, blood transfusions, anti-biotics, plastic surgery and huge advances in prosthetic limb technology.

WW1 gave doctors and physicians an unprecedented number of patients to trial and perfect treatments. Faced with the unique nature of wounds sustained in World War One, doctors and scientists developed a number of innovative techniques and tools, to tackle burns and infections. They included, Alexander Fleming, the bacteriologist best known for his discovery of penicillin, who worked during the war, on alleviating the symptoms of gas gangrene.

Lieutenant General, Sir William Boog Leishman, a Professor of Pathology and army Doctor, developed new typhoid fever inoculations. Leishman’s work saved an estimated 130,000 lives as well as preventing 900,000 men being invalidated out of the army.

Sir, Robert Jones Thomas, who developed a splint to keep the leg immobile. The splint prevented further bleeding (caused by the movement of broken bones) and helped to align the fractured pieces. By keeping the leg secure, it furthermore made the men more comfortable during transportation. The “Thomas splint” was introduced to the Western Front in 1916, and between then and 1918 the splint reduced the rate of mortality from fractures, and from fractures of the femur in particular, from 80% to 20%.

Before the First World War prosthetic legs and arms were mostly wooden, heavy and caused pain and discomfort. There was little regard for functionality and, as a result, were almost useless as limb replacements. A new generation of comfortable prosthetic limbs was created in the 1920s made of light aluminium with adjustable joints.

Arthur Hurst, an army major at Seal Hayne, pioneered revolutionary treatments for ‘war neurosis’, which had puzzled doctors who often prescribed harsh treatments such as electric shocks and solitary confinement.

Hurst believed in occupational therapy. The men worked on a farm in the peace of the countryside and were given intensive therapy sessions, including hypnosis. 90% of his patients were cured.

Sir Arthur Sloggett was another career army medic, and Director General of Army Medical Services when the war began. His was a role of management and leadership, which could have been conducted from London, but when he saw the chaotic nature of initial efforts, he relocated to France. The part of his job based at the War Office was passed to Sir Alfred Keogh, while Sloggett reorganised medical care on the ground for millions of troops. Sloggett and Keogh together quietly transformed Britain’s military medical care. They increased supplies of antiseptic and anaesthetic and oversaw the provision of field dressings to all soldiers, allowing swift emergency treatment and better care down the line.

Sir Anthony Bowlby was a volunteer surgeon for the British forces during the Boer War, who modernised ways of working. In particular, he fought against the practice of bringing men far from the front before treating them. The sooner they were treated the more likely they were to survive, and that meant moving medical services closer to the battle zones. He created Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS), bases that effectively acted as miniature hospitals a few miles behind the lines. He pushed them into specialising in the most important treatments for the wounded, including head injuries and abdominal wounds. CCS took on an increasingly important role, providing more and more medical services including surgery, to ensure that men were treated as quickly as possible.

Captain, Harold Gillies, was a New Zealand born, surgeon, working in the UK, who pioneered plastic surgery during the war. He worked with Auguste Charles Valadier, a dentist, replacing jaws that had been destroyed by gunshot wounds. Gillies’ aimed to make patients look as similar to their pre-injured state as possible. In 1920, he published a book instructing other surgeons on how to achieve this. Operating from 1917 until 1925, his hospital at Sidcup became a major centre for facial injury and plastic surgery. The service treated 5000 men for facial injuries and included separate units for British, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand patients.

Anna Coleman Ladd, works on the mask of one of the soldiers. The masks would be painted to try and resemble the soldiers’ skin colour, and each piece would be adorned with some form of string or eyeglasses in order to keep it in place.

Anna Coleman Ladd, works on the mask of one of the soldiers. The masks would be painted to try and resemble the soldiers’ skin colour, and each piece would be adorned with some form of string or eyeglasses in order to keep it in place.

American Army Captain, Oswald Hope Robertson, improved Blood transfusions, to prevent patients from dying of shock or blood loss. He showed that stored universal donor or cross-matched blood could be given safely and quickly to forward medical units. As a result, by 1918 transfusions were being performed much closer to the front lines than clearing stations, as a means of improving survival during evacuation of the wounded to field hospitals. Primarily, blood transfusions were used to treat severe haemorrhage and shock, before an operation took place. However, transfusions could also aid with carbon monoxide poisoning and wound infection, and so were increasingly used during and after operations. Sepsis, an all-too-common hospital malady back then, was beaten with the invention of antiseptics during WW1.

In France, vehicles were commandeered to become mobile X-ray units. New antiseptics were developed to clean wounds, and soldiers became more disciplined about hygiene. The sheer scale of the destruction meant armies had to become better organised in looking after the wounded, surgeons were drafted in closer to the frontline and hospital trains were used to evacuate casualties.

Those lessons are just as relevant in war zones today. The role of a first responder is commonplace in the armed forces today, but it was only during World War One that it was realised medical expertise was needed closer to the action.

The scientist John Scott Haldane, was another innovator. He travelled to the front to research what poisonous gases were used and how to prevent their worst effects. One of his inventions was an oxygen apparatus, which was based on the finding, that increasing the blood’s concentration of oxygen was one of the best way to work against the deadly gases as they damaged the lungs. It could treat four people simultaneously. The apparatus became a crucial innovation for the gas treatment units that were soon stationed near the front lines.

French radiologist, Etienne Henrard Hirtz (1870-1941) developed a brass compass to accurately determine where bullets were located in the body, especially the brain. Bullets could then be removed surgically with precision, thereby reducing damage to the surrounding areas of the body. Portable fluoroscopes and electromagnets were also used to locate buried shrapnel.

Front line medics were trained and given medical kits, with instruments for surgery as well as other items meant for processes, like caring for wounds, anaesthetising and sterilising.

The British designed the flexible, Colt Stretcher in 1916, for use in narrow trenches. It allowed the wounded to partly sit rather than lie prone. The yokes at each end, meanwhile, allowed the bearer’s shoulders to carry the brunt of the weight, keeping their hands free and the patient low – all of which helped to prevent further injury from explosions or attacks.

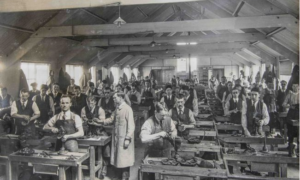

The First World War, for the first time, put new emphasis on rehabilitation and continuing care. The idea arose that even severely disabled soldiers should be rehabilitated and returned to the job market in order to be able to earn their own income and not simply live off a pension. Common occupations were gardening, basket-weaving, knotting and carving. Some hospitals had fully equipped workshops with instructors available to help disabled patients become well enough to be able to take up their original job again, or to re-educate them for a new career.

During the course of the war, the military medical authorities in all warring countries increasingly started to establish specialized hospitals and to build centres of competence in order to treat patients more efficiently. Hospitals were divided up, and specialised as centres for limbless men, neurological units, orthopaedic units, cardiac units, typhoid units and venereal disease. In this way, patients found themselves in the same ward as other patients with similar ailments. This could strengthen the sense of fellow suffering and lift morale – an effect consciously created by military doctors and authorities.

To meet the needs of hundreds of thousands of amputees. A number of hospitals opened with the sole purpose of helping men with amputations, two of the best known being, the Princess Louise Scottish Hospital for Limbless Sailors and Soldiers, based in Erskine, near Glasgow, and the Queen Mary Convalescent Auxiliary Hospital, based in Roehampton. Amputees were found work, making artificial limbs alongside established tradespeople. At institutions like Erskine and Roehampton workshops were set up to teach patients to do everything from bakery, boot and brush making, joinery and hairdressing, to basket weaving and bee keeping. Tools were also adapted for men who had lost limbs, especially for those who were using artificial arms. By 1922, the Government Research Laboratory finished designing what would become known as the ‘Standard Wooden Leg’, which was to be manufactured by all limb makers from a prescribed pattern. 495,545 men were supplied with an artificial limb, mobility aid or other surgical appliance. However, the fitting of a prosthesis was not the end of the matter, amputees would often live in pain for the rest of their lives and suffer from other conditions such as osteoarthritis and insomnia. There were also consequences for families, communities and work places who had to adapt to their war wounded.

Hospitals for shell shocked soldiers were also established in Britain, including (for officers) Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh; patients diagnosed to have more serious psychiatric conditions were transferred to the Royal Edinburgh Asylum. The Maudsley Hospital, at Denmark Hill, Camberwell, was funded by the Ministry for two years until November 1920, and treated 2,231 veterans for shell shock. The East Leeds War Hospital (now St James University Hospital) was another treatment centre for shell shock patients.

Asylums, such as Beaufon in Bristol, were also converted into war hospitals for psychiatric patients.

A new war hospitals was built in Cardiff. Dr Edwin Goodall was famed for his Therapeutic techniques, as the medical superintendent of the Welsh Metropolitan War Hospital during the war.

Volunteer associations trained and employed a huge number of nurses and other medical auxiliaries, provided civil physicians, medical equipment, hospital laundry, furniture and complex administrative services. Most importantly, the Red Cross and other volunteer aid societies financed and managed a huge number of auxiliary hospitals – although they remained in the control of military surgeons. Some hospitals were established on grounds belonging to the private estates of aristocrats and wealthy philanthropists.

In Britain these included hospitals at Dunham Massey, Knutsford, and Bishop’s Knoll. Another interesting example is Endell Street Military Hospital in London, a facility entirely staffed by women, most of them militant suffragists.

Civilian aid was a fundamental element of hospital care, and one which prevented it from collapsing given the enormous number of sick and wounded soldiers. December 1916 to August 1919, the Army Spectacle Depot provided more than 22,000 eyes to victims across Britain.

WW1 – War Pensions & Grants

There were over 11 million hospital admissions during WW1. Governments were slow to respond to the needs of the wounded and their families. Due to the high numbers of widows, the War Office were unable to cope with claims and had to rely on a mix of ministry and charities to fulfil their obligations. In 1915, the War Office had only 20 staff, but by 1919 their staff numbered 4,000.

It was not until February 1917, that Britain established the Ministry of War Pensions. The Ministry of Pensions took over from the Admiralty, the War Office, the Army Council and the Chelsea Hospital Commissioners. It was responsible for administering all naval and military death and disability pensions and allowances, including naval and military nursing services, arising from the First World War or granted prior to 18 September 1914. A Special Grants Committee was created to assess war widows’ eligibility for War Widows’ Pension. The Special Grants Committee’s decision making process was famously flawed and widely criticised: the committee determined whether women were worthy of state support by assessing – sometimes by covert means – their moral and sexual behaviour, parenting practices, and housekeeping. Yet, at the same time as the state was policing and prescribing women’s domestic conduct, they also forced women to leave the home to work by setting pension rates so low that they barely covered basic living costs.

It should be noted that the Ministry of Pensions was set up primarily to reduce the rising costs of war pensions, rather than spend more money to help the victims. This shaped the bureaucracy and attitudes towards helping war widows and the British wounded.

The process of being awarded a war pension was often long and complicated. Disabled men were awarded interim payments while their injuries were assessed. These were renewed on an annual, bi-annual, and even quarterly basis, requiring a medical examination at each renewal. There was no automatic right to a war pension. Widows had to apply for their pensions, and over bearing bureaucracy often deterred people making claims. Pensions started from date of application and were often paid months after the soldiers death, causing great family hardship. Their husband’s death had to be entirely due to war service and his death occur within 7 years of his entirely war service injury. Disabilities due to accidents could be disqualified if a man was shown at fault for the accident. The amount of payment, which could be a one off gratuity rather than a regular pension, varied according to the severity pf the impairment. Applicants had to be married at the time of the injury and be deserving of the grant of a pension. They had to have a certificate signed by a magistrate and a police officer to demonstrate they were deserving. There was concern by the authorities that women could not manage money and soldiers’ wives were drunkards, so any money they received would be used for drink. There was even an investigation into soldiers’ wives and drink in 1915. It was also thought by the authorities that women were getting married to soldiers just to claim a pension if he died. Women had no vote at the time to contest these regulations. They needed to beware of “concerned citizens” with a grudge snitching on them. Even taking in a male lodger they might be seen as “taking up” with a man. They could be taken to court, their pension suspended, paid in trust, or via coupons at a particular shop, or withdrawn completely. At first widows of husbands who were “Shot at Dawn” could not claim a pension, but later it was argued that a wife had no control over her husband’s behaviour and they were allowed a widow’s pension. It was somewhat back dated, but not to the date of their husbands death. Widows could take a job and many women did, taking on war work to release a man to fight. After the war was over women were laid off in favour of disabled ex-soldiers and sailors.

As war injuries worsened and men succumbed to their war wounds, war pensions and costs increased. It was estimated that the number of British war widows increased from 192,000 after the war to 230,000, in 1921. Pensions were not generous and depended on rank. British Widows were the lowest paid at 16 shillings/6 pence a week, whilst the highest, the Canadian widows, received more than double the payment of their British counterparts.

After the war, Britain sought to cut government spending to manage the national debt, which rose from £754 million in 1913 to £7,414 million in 1919. The Ministry of Pensions’ remit became to protect public spending and it developed a reputation for parsimony. It applied a strict formula to award pensions, which limited discretion to take account of an individual’s needs. In 1917, £40 million pounds was spent on disablement pensions (Ministry of Pensions, 1919) and by 1921, a total of 1.3 million pensions were awarded.

Overall, the Ministry of War Pensions reduced spending by almost 50 per cent, from £106,367,000 in 1921 to £54,066,000 in 1930. This reduction was achieved in numerous ways. Chiefly all pension claims were viewed with suspicion and required a high bar of proof to qualify. Only servicemen with a 40-100% disability could claim a War pension. Servicemen with skeletal injuries (to spine, wrist, hip, knee, ankle and foot), or muscle pain, like Rheumatism, Arthritis, Synovitis and Myalgia, and others with Nephritis (kidney disorders), venereal disease, dysentery and Malaria, rarely qualified for a full war pension, even when it was aggravated or attributable to war service. The 1921 War Pensions Act, introduced a seven year time limit on claims, from the time a serviceman was discharged. This prevented further liability and reduced on going costs.

In 1925, Neville Chamberlain introduced the Widows’, Orphans’, and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act, which built on the National Insurance Act (1911). This severely limited the number of state-supported war widows. It specified that women whose husbands had not been killed in military service were ineligible for War Widows’ Pension. It also determined that only those who were married to insured men and widowed after 4 January 1926 were eligible for state support. Widows of insured men who had died before this date only received a War Widows’ Pension if they had children younger than fourteen, and provision would cease once their children exceeded that age. The 1929 amendment bill lifted these limitations, to a certain extent, by awarding War Widows’ Pension also to women who were widowed before 4 January 1926, providing they were of or above the age of 55, or had children who were under sixteen years of age. This meant younger, childless war widows as well as war widows with children older than sixteen were not eligible for War Widows’ Pension.

By 1926, almost half a million pensioners, with around 50 per cent of those in receipt of a pension scaled at 20 per cent or less, were given a lump sum or gratuity defined as a ‘Final Award’. The 84,700 pensions awarded after the war for shell shock were reduced to only 32,970, by 1927. There was a subsequent reduction in medical facilities: while 332,000 disabled pensioners were undergoing treatment in 1921, this figure stood at just 41,000 by 1930. By 1926, the national network of 29 “Specialist medical clinics” for shell shock, had all been closed. Hence, most British servicemen suffering from this trauma had to manage themselves or with the help of charities.

The Ministry then often covered the cost of a veteran’s health care via “Capitation” grants for treatment in public hospitals or via their personal General Practitioners. A subsequent associated reduction in Ministry staff resulted in 21,685 departmental staff in 1921, being reduced to just 3,795 a decade later.

War Gratuity

Unlike the service gratuity, the war gratuity paid an amount based on both the rank of the man and the length of service (home and/or overseas) – up to a maximum of 60 months service between 4th August 1914 and 3rd August 1919.

Privates

These ranged from a full pension for the loss of two or more limbs, loss of sight and very severe facial disfigurement, to 50% for amputation of a leg below the knee or right arm below the elbow, and 20% for the loss of two fingers either hand. Many considered the pensions inadequate to live on.© Black Country Museum.

Service with overseas service

£5 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£5 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

Corporal

Service with overseas service

£6 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£6 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

Sergeant

Service with overseas service

£8 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£8 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

Colour or Staff Sergeant1918

Service with overseas service

£10 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£10 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

WO 2

Service with overseas service

£12 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£12 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

WO 1 Service with overseas service

£15 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£15 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

Extract from Ministry of Pensions’ classification for military disablement pensions (Ministry of Pensions, 1919).

War Pensions

Assessing doctors were required to rate men as “per cent” disabled from 100% dropping by 10% stages until 20% was reached, when they could then use the notion of ‘less than 20%’. Many used the bands of, for example, 14-19%, or small percentages of 5% or even 1%. A Ministry of Pensions leaflet dated c.1920 set out the tariff of proportion of pension corresponding to degree of disablement, in relation to various conditions. 100% disability accrued a weekly pension of 40/-, with additions for wife and children. A period for which the pension was payable was specified, but sometime ‘for life’.

The following is a percentage of disability and % of pension entitlement, with examples of specific disability required for pension entitlement.

100% – Two or more limbs, or arm and eye, leg and eye, or both hands, or all fingers and thumbs, or hand and foot, Total loss of sight

Permanently bedridden, Total paralysis, Total permanent disablement through internal, thoracic or abdominal organs, Lunacy, Head or brain injuries which permanently disabled, Very severe facial disfigurement

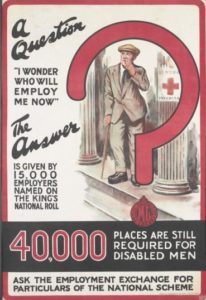

Businesses that employed the men were given preferential consideration for contracts and could display the Royal Crest. However, the tendency was to employ those with low level disability, leaving the severely disabled out of work.

The state did not create sheltered employment opportunities or provide retraining. Britain was the only European state to rely entirely on voluntary effort to employ disabled ex-servicemen.

90% – Amputation of right arm through shoulder

80% – Amputation of leg at hip with stump, not more than 5 inches, of right arm below shoulder with stump not more than 6 inches, of left arm through shoulder, Severe facial disfigurement, Total loss of speech, Loss of both feet

70% – Amputation of leg below hip not below middle thigh, of left arm not more than 6 inches below shoulder or right arm not more than 5 inches below elbow, Total deafness

60% – Amputation of leg below middle thigh or through or not more than 4 inches below knee, or of left arm not more than 5 inches below shoulder through or not more than 5 inches below elbow, of right arm more than 5 inches below elbow

50% – Amputation of leg more than 4 inches below knee, or of left arm more than 5 inches below elbow, Loss of vision in 1 eye

40% – Loss of thumb or 4 fingers of right hand, loss of 2 toes of both feet above knuckle, Lisfranc operation, one foot

30% – Loss of thumb or 4 fingers of left hand, loss of 3 fingers of right hand

20% – loss of two fingers on either hand

The issuing of Pensions became a slow and complex process. In 1919, the Ministry of Pensions were employing only 1,200 inexperienced staff to deal with millions of claims. Payments were made from the time of the application, not the death of the victim and it could take six months before a decision was made. Payments stopped on appeal and were not backdated. Payments were often late, meagre and there was even criticism that some pensions were being decided by “seventeen year old girls”. Only servicemen with a 40-100% disability could claim a War pension. The 40 shillings weekly payment for 100% disability was not enough and was later reduced to 27s. 6d for full disability. The flat rate for a mother who lost a son was only 5 shillings per week. Although these awards were later increased they were still inadequate. A full disablement pension of 40 shillings per week, was less than what was earned by an unskilled builder (84 shillings and 6 pence per week), a coal mining labourer (99 shillings and 3 pence per week) or a skilled coal getter (135 shillings and 6 pence per week). Pensions did not increase for dependants and there was no government plan to re-train ex-servicemen or help them return to employment.

There was great dispute over what constituted a disability and what percentage should be awarded. One case was Private, William Hill, 2nd York and Lancaster Regiment, of Liverpool Street, Hull. Called up for service in 1917. He was gassed, lost sight in both eyes and had his left leg amputated. His wife and two sons were awarded a weekly war pension of just 23 shillings and sixpence, in December 1919. Fitted with an artificial leg, he found little work due to his war injuries. He eventually died at Hull, in 1933, aged 41. One of eldest war pensioners, was Sapper, Henry Breckon, Royal Engineers, of 400, Bricknell Avenue Hull, who died on 8th May 1986, some seventy years after being injured.

Many of the women whose husbands, fiancés, boyfriends and brothers were killed in the First World War, felt that they too had served their country by sacrificing their men to war, and that their loss deserved recognition. Women’s lives had been dramatically reshaped by these losses and left many families in financial hardship. However, only married widows were entitled to a War pension. Unmarried partners and separated wives faced many barriers. Widows had to prove their husband’s deaths were due to war service and were only awarded a portion of their husbands pension. In 1924, the original stipulation that a man must die within seven years of his injury was removed and widows could claim two thirds of her husband’s disability pension. However, confusion and disputes continued as the payment system could not account for individual needs.

Allowances paid to mothers who lost their only son, or other dependants, like a husband or other sons, could vary widely between neighbours, as well as regions. There were arguments over adequate compensation, what a man’s skills as a “breadwinner” were worth, their earning potential and what was “reasonable” standard of living. Widows were often worse off financially, than the wife of a soldier still serving. The treatment of children introduced further issues on allowances and payments. For example, no Grant or allowance was made in respect of children that were born nine months after demobilisation, yet these needed to be provided for if men were incapacitated. The payment of pensions and allowances to dependants became controversial, difficult to reconcile and caused dissatisfaction for decades. *

Many men who may have been entitled to pensions, never claimed them. Others who were originally granted pensions, tired of attending Medical Boards to be reassessed, relinquished them. The widows of these men were left without a claim, unless they could prove a continuous medical history of the complaint leading to their husband’s death and that it was direct result of war service. Even women tired of the intrusive nature of the Pension Ministry and forfeited claims.

The Ministry of Pensions main role was to protect public expenditure and evade paying pensions where possible. It went to considerable lengths to investigate cases before accepting liability. They often trawled through pre-war medical records and Friendly Society Insurance Policies to prevent claims. For example, coal miners admitting to chest troubles prior to enlisting, found claims of gas wounds rejected. The post war depression forced Governments to reduce public spending further. Compensation for “shell shock” which was not deemed a legitimate medical condition at the time, had a particular hard time securing suitable pensions. It is estimated that there were 250,000 shell shock victims after the war, but the UK government awarded only 84,700 war pensions and by 1927, only 32,970 were still in payment. By 1927 war widows were being encouraged to remarry and given a lump sum to do so. Statistics show that 98,500 war widows remarried under the scheme.

The 37,199 ex-servicemen who settled abroad via the British Government’s Overseas Settlement initiative became increasingly isolated and marginalised. (16,514 former British Servicemen, settled in Australia and around 11,500 pensioners emigrated to Canada and the USA).

Widows had to be married to the soldier at the time of injury. Men marrying widows after the war could not make a claim. The Victorian class system often prevailed. Officers were treated more leniently than other ranks and their children were given education grants to enable them to have ‘the education they would have received if their father had not been killed or disabled’.

Widows had to be seen as “deserving” and it was thought women were marrying wounded soldiers to claim a war pension. The Ministry of Pensions held all the cards. Pension claims were based on the man’s service record and these were sometimes incomplete or incorrect, but they were held sacred by the Ministry, making it difficult for claimants to dispute. For example, gas victims, after the war were refused help, because their service records referred to gunshot wounds, rather than gas. The Pension Appeals Tribunal established in 1917 was still part of the Ministry of Pensions and still put up artificial barriers to deter claims. For example, 12 Tribunals consisting of a lawyer, a discharged serviceman and a Doctor, were set up to hear appeals and disputes. However, the Pensions Appeals Tribunal was only available to those who could afford legal representation and were often located in places which deterred claimants. Portsmouth for instance, an important Naval base which had suffered many war casualties, held their Tribunal in Exeter, a long expensive train ride away, beyond the means and convenience of many impoverished war widows.

The Ministry of Pensions were intrusive, stacked against poor women with little means, and often overturned Medical advice, seeing Doctors as “too soft”. They could refuse, cut and revoke pensions and had the power to remove children from their mothers for “neglect”. By March 1924, there were 18,157 orphaned children in the care of the department, there were also 3,181 whose mothers were alive; of these, 668 had been committed into care by the Special Grants Committee under the Children Act, 1908.

The Pension Ministry found it easier to refuse claims of soldiers who had died in training or not seen battle, even though these home soldiers were elderly and did hazardous war work in poor conditions. For example, a 1917 Parliamentary Debate revealed 100,000 men were unfit to be conscripted, but these men were still expected to serve in some capacity. The widows of the 343 men and 3 officers who were shot for cowardice or desertion during the First World War, were left destitute until January 1918. Widows of men who had committed suicide were also refused a pension until March 1917 . Widows of men who died from disease, could also be refused a pension if ‘the man’s death from either disease or injury was due, or partly due, to his own fault or negligence’.

Many thousands of First World War widows received no pension, or had it taken away from them. Between October 1916 and March 1920, the Statutory Committee and the Ministry between them initiated at least 40,000 investigations. In a single year between March 1918 and March 1919, 6,302 women lost their separation allowance and 939 war widows forfeited their pensions due to “unworthy” behaviour. By 1936 the numbers of war widows’ pensions being paid had fallen to 129,500 and 117,000 war widows had married again, although many widows cohabited, rather than remarried, as they lost their war pension on remarriage.

In 1937, when there was less scrutiny, the Ministry of Pensions withdrew pensions saying their original decision 20 years before was incorrect. This was particularly cruel for widows who had been left to care for their disabled partners largely on their own. Personal wealth greatly affected the outcome and future life chances of disabled veterans. Wealthier disabled ex-officers like Sir Jack Cohen, MP, who had lost both legs at Passchendaele, could afford to pay privately for a custom-fitted prosthesis, a motorised wheelchair, a personal attendant, a lift, home aids, and a car adapted to their needs. Meanwhile, other disabled veterans were sometimes unable to leave institutions because their families did not have access to adequate housing.

In Britain during the late 1930’s, 639,000 ex soldiers and Officers were still drawing disability pensions. This figure includes 65,000 men whose disabilities were not physical, but mental. Some servicemen were so traumatised by the experiences in the First world war, that they spent the rest of their lives in hospital. About 25% of those discharged from active service during the war were ‘psychiatric casualties’. Most were suffering from shell-shock, a condition viewed by the public as a sign of emotional weakness or cowardice. A growing number of centres, such as the Royal Victoria Hospital in Southampton and Seal Hayne in Newton Abbot specialised in such cases. When it came to housing, there was also no comprehensive government plan to provide suitable long-term accommodation. Developments in disabled housing, were largely driven by the voluntary sector, rather than the State, along with early initiatives in rehabilitation and retraining and major advances in prosthetics and plastic surgery. Some of these private and voluntary initiatives provided housing, training and employment for disabled servicemen and their families. Sir Oswald Stoll, a theatre Entrepreneur, built the War Seal mansions, in Chelsea, between 1917-1923. These 157 adapted family flats, for limbless ex servicemen, included widened doorways, wheelchair ramps and specially designed bathing facilities. The Enham Village Centre in Hampshire, provided family homes, for 150 men, alongside medical and industrial training facilities. Between 1917-1922, Bernard Oppenheimer (1866–1921), a South African-British diamond miner and philanthropist, established a diamond factory in Brighton, to train 500 men with lower limb amputations to cut and polish diamonds from South Africa. A Painted Fabric workshop was also set up in Sheffield to help disabled men and their families become fabric printers and dressmakers and traded until 1959. The Earl Haig Poppy factories in Richmond and Edinburgh ensured that disabled ex servicemen at work was a regular feature in the press.

Pensions Abroad.

Overall, some 15 million men were wounded in WW1 and this had enormous social, economic, demographic and political consequences. In 1919, the newly formed Weimar Republic, on the verge of wild inflation, bankruptcy, and political chaos, discovered that Germany was suddenly responsible for some 2.7 million disabled veterans, 1,192,000 war orphans, and 533,000 widows. Almost all of these people were younger than thirty and the new German Republic might be responsible for them for another half-century or more. Calculating war pensions proved expensive and contentious and only 800,000 Germans received invalidity pensions.

France had the same number of disabled as Germany, 630,000 soldiers’ relatives and about 1.4 million widows and orphans. Countries like Britain and Italy had more than a million victims. The numbers in smaller countries were far from irrelevant: in Czechoslovakia 575,000 disabled and survivors represented approximately 4 percent of entire population. The situation in Austria, Hungary, Romania and Poland was similar. In 1923, the International Labour Organization (ILO), based in Geneva, estimated around 7 million war disabled, although it did not include statistics from some countries.

The victims of the First World War were not confined to the battlefield. The attempted genocide of the Armenian people cost between 800,000 and 1.3 million lives. As many as 750,000 German civilians died as a result of the Allied Trade blockade. More Serbian civilians (82,000) died as result of the conflict, largely from disease and starvation, than Serbian soldiers (45,000).

Millions of soldiers and civilians alike were killed by the virulent Influenza pandemic that left none of the warring countries untouched in 1918 and 1919. In addition, there were the many millions of largely silent victims of the Great War: the widows, parents, siblings, children and friends who lost loved ones. Historians have only recently turned their attention to the many ways in which survivors sought to cope with the grief caused by these innumerable personal losses. During the war, in a brief essay entitled “Mourning and Melancholia,” Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) identified grieving as a complex, painful, and psychologically crucial process which had become, because of the war, an immense social problem.

Notes: To appreciate some of the complexities of awarding war grants and pensions, it is worth reading Hansard Parliamentary Debates. Here is a link to one particular debate held in Parliament on 15/04/1919. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1919/apr/15/war-pensions-and-grants .See also https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1032373216656648 and ‘Expenditure of the MoP’, PIN 15/2601, NA“.

For some analysis and case studies on war Pensions see:-

https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/health-in-returning-veterans-of-the-first-world-war-the-impact-of-wounds-agassing-injury-and-medical-and-psychological-conditions-from-a-study-of-the-pension-ledgers-by-dr-peter-hodgkinson/

The emphasis was on pioneering vocational training, often involving adapted forms of technology, including typewriters and telephones. Pursuits such as music, dancing and sport were also encouraged. The men learned braille and, once they left St Dunstan’s, were given symbols of independence, such as braille watches.

For the majority of disabled veterans who didn’t need lifelong care in an institution there was an urgent need to provide independent living, suitable homes and a way of earning an income for them and their families. With no national plan from the government, the voluntary sector stepped in, building new housing ranging from cottages, to mansion flats and entire villages.

This memorial village, built after the war and including sheltered workshops, was specifically created for disabled soldiers and their families. Such villages were few and far between and were reliant on voluntary donations. The leading landscape architect and town planner of the time, T.H. Mawson saw such segregation as protecting disabled veterans from ‘the struggle of the crippled man with those who are able-bodied.’ Other voices felt that disabled veterans’ housing should be integrated within existing urban communities.

This move was made possible by the British Legion, which was founded 15 May 1921 to campaign for better support for disabled ex-servicemen and women.