Hull Royal Infirmary Naval Hospital

The first hospital organised by Lady Nunburnholme (Lady Marjorie Wynn-Carrington), was the Naval Hospital at Hull’s Western General Hospital (now called the Hull Royal Infirmary). It was located at Argyle Street, Hull, next to today’s Hull Royal Infirmary. Originally opened in 1914, to help Hull’s poor and sick people from the nearby Workhouse, she persuaded the Board of Guardians to donate the East and West wings of the hospital to help front line casualties arriving at nearby Paragon Station on special ambulance trains. In April 1917, it became a naval hospital for injured sailors. The Naval hospital was equipped by Lady Nunburnholme and Lord Glenconner and staffed by trained Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurses. It had 220 beds and was initially used as a military hospital for the sick from the Humber Garrisons, but by early 1917 had been entirely taken over by the Navy, receiving a weekly Royal Navy Ambulance Train. It was to be used to treat casualties from the military and navy with the East Riding Territorial Branch of the St John Ambulance Association Voluntary Aid Committee supplying nurses and staff.

The hospital started accepting casualties almost immediately and between August 1914 and January 1917, almost 2,500 patients, mainly soldiers and military personnel, were treated in Hull. By January 31, 1917, Britain’s naval base hospitals were under intense pressure because of the number of casualties from the war at sea, so the Admiralty asked that the hospital should only accept naval casualties.

Six large and six smaller wards were used to treat 204 men and 16 officers. A matron and 12 trained sisters ran the wards with the nurses coming from the Kingston and Western Division of the St John Ambulance Association Voluntary Aid Detachment. By the time the hospital closed in January 1919 following the end of the war, it had treated a further 4,000 patients.

Lady Sykes Hospital

This was equipped by the late Sir Mark and Lady Sykes and based in the Metropole Hall, West Street in Hull. Staffed by trained VAD helpers this hospital transferred to France. It returned to Hull after the war and closed in January 1919.

Reckitt’s Hospital

The Reckitt’s company converted its social hall into a factory hospital. It was Hull’s third hospital with 45 beds, organised and financed by Mr and Mrs P Reckitt. This VAD run hospital opened on the 9th December 1914 and closed in January 1919. In the 4 years and 3 months that it was open, the Reckitt’s hospital treated 2,910 patients. Colonel Tatham from the Humber Garrison Medical Service wrote; “the patients who have been there, greatly appreciate the care and kindness bestowed upon them. Many of them have told me, that they were so looked after and received so many little extras and kindnesses, that Reckitts’ was the hospital that men wished to get into if they could.” Sir James Reckitt also billeted a large number of soldiers in their grounds and offered to house a large number of Belgian refugees.

Hull’s Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD’s)

The Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) was a voluntary unit of civilians providing nursing care for military personnel in the United Kingdom and various other countries. Although VADs were intimately bound up in the war effort, they were not military nurses and they were not under the control of the military. The VAD nurses worked in field hospitals, close to the battlefield, and in longer-term places of recuperation back in Britain. Most volunteers were of the middle and upper classes and unaccustomed to hardship and traditional hospital discipline. Military authorities would not accept VADs at the front line. Initially, the VADs were officially recorded as being assigned to the one hospital, but as time went on, they also worked – often unofficially and only for a few days at a time – at a number of hospitals in their local area, potentially providing a continuity of care to

certain patients when hospital transfers occurred. By 1916 the military hospitals at home were employing about 8,000 trained nurses with about 126,000 beds, and there were 4,000 nurses abroad with 93,000 beds. By 1918 there were about 80,000

VAD members: 12,000 nurses working in the military hospitals and 60,000 unpaid volunteers working in auxiliary hospitals of various kinds. Some of the volunteers had a snobbish attitude towards the paid nurses. VADs were an uneasy addition to military hospitals’ rank and order. They lacked the advanced skill and discipline of trained professional nurses and were often critical of the nursing profession. Relations improved as the war stretched on: VAD members increased their skill and efficiency and trained nurses were more accepting of the VADs’ contributions. During four years of war 38,000 VADs worked in hospitals and served as ambulance drivers and cooks. VADs served near the Western Front and in Mesopotamia and Gallipoli. VAD hospitals were also opened in most large towns in Britain. Later, VADs were also sent to the Eastern Front. They provided an invaluable source of bedside aid in the war effort. Many were decorated for distinguished service.

At the end of the war, the leaders of the nursing profession agreed that untrained VADs should not be allowed onto the newly established register of nurses.

The VAD system was founded in 1909 with the help of the British Red Cross and Order of St John. By the summer of 1914 there were over 2,500 Voluntary Aid Detachments in Britain. Of the 74,000 VAD members in 1914, two-thirds were women and girls. Hull and East Riding provided 6,000 VAD members. By the end of the war, there were over 200,000 VAD members and 400 VAD hospitals had been established throughout Britain, commanded by Charles Wilson, Lord Nunburholme, one of the heirs to the Hull based, Wilson Shipping Company and who also recruited the Hull Pal Regiments and the Hull Royal Garrison Artillery Units for the war effort.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Hull’s VAD members eagerly offered their service to the war effort. In September 1914, they provided extra beds for minor ailments at the Hull, Naval Hospital to boost recruitment. They provided woollen garments, socks flannel shirts, knitted cardigans, and sweaters to help comfort and sustain fighting men and prisoners of war. On Christmas Eve 1914 every officer and man in the Hull Pals and Heavy Artillery received a Christmas Card from Lord Nunburnholme, consisting of a picture of St George slaying the dragon with the badge of the East Yorkshire Regiment and coloured bands representing the distinctive armbands worn by the different battalions and batteries before they received their uniforms.

On 22/11/1915, VAD’s, British Red Cross and St John’s Ambulance workers were officially recognised and given their own uniforms. They were recruited at the Peel Street, Office, Hull, which

needed nurses, typists, kitchen, Housemaids and cleaners. Applicants, had to be aged between 21-48, and were recruited at Peel House, between 3-5pm, on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Fridays. By August 1916, 94 classes had been held to train the recruits. By August 1918, 6,000 VAD’s members had been issued with certificates (HDM 14/08/1918).

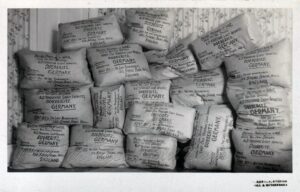

The Hull VAD branch was a well run, fund raising machine, industrious and productive. For example, it established a central Fund, which raised £2,600 for Christmas puddings for East Yorkshire soldiers (Hull Daily Mail 24/10/1916). A meeting chaired by Lady Nunburnholme, on 20/03/2017, showed receipts in the previous six months, of £9,859 and a balance of £3,307. Over £2,550 had been received in response to their £5,000 appeal for Prisoners of War. In the last two months, they had dispatched 6,250 pair of socks, 874 shirts, 925 Mufflers, 1,130 mitts, 602 helmets and 14,000 servicemen had passed through their “rest Station” at Hull Paragon in the last 6 weeks and the station was practically self-supporting.

On 15/04./1917, a new St John’s VAD Hospital was opened on the site of Newland School for Girls, by Lady Marjorie Nunburnholme, Colonel, George Easton and Major, Hammersley Johnson (St Johns). The following month the Council arranged a free Telephone service for this hospital, on Cottingham Road, Hull. This was followed by a Royal Visit to the hospital on 16/06/1917. Guests, such as Private, Blackshaw, an escaped prisoner of war, thanked the Hull VAD for two and half years of weekly parcels (HDM 31/07/1917).

The Hull VAD’s were unpaid, volunteers, who showed splendid conscientiousness and self-sacrifice. They inspired the creation of the Women’s Army Service Corps and Women’s Royal Navy Corps, in January 1918. VAD’s were given a “Red Efficiency Stripe” to raise their status in military hospitals and a VAD recruiting Parade was held in Hull, on 08/04/1918.

Miss Gladys Eleanor Runton, a Hull VAD nurse, died of influenza, caring for sick patients (19/10/1918).

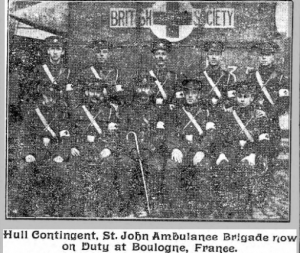

Hull’s St John’s Ambulance Association, was part of the British Red Cross Organisation and formed in Hull, in 1883. During the war, the St Johns Ambulance (Hull Corps) had over 1,000 members, serving on all fronts, and was the largest in England. On 23/04/1915, it held a parade at Hymers College, which included 400 staff and 250 nurses in their distinctive uniforms. It provided 500 voluntary nurses for VAD Hospitals, in and around Hull and staffed the Paragon Rest Station. It helped remove 5000 patients from hospital trains to the Hull Naval and VAD Hospitals, via three motor ambulances (contributed by Hull people, the Pacific Club and Hull Showmen Guild and the Hull Co-operative Society), and two horse ambulances. St John’s staff made 700-800 beds available for casualties and sick, in Hull. Many joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and the three Voluntary Field Ambulance Units (one composed entirely of Hull men), under the command of Major, Hammersley Johnson. The volunteers of the Hull VAD, St Johns and British Red Cross showed marvellous enthusiasm and self-sacrifice, undertaking unpaid, work at all hours, meeting hospital trains and removing the sick and wounded (HDM 11/05/1918)

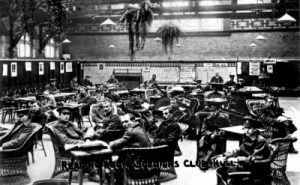

Hull’s Paragon Station was the location for a Hull Rest Station and Canteen during the First World War. It was set up in September 1914 and run by women who were part of the Voluntary Aid Detachment. With so many men leaving Hull to go to war, Rest Stations and Canteens provided food, drinks and essentials, such as stamped stationary for those leaving or arriving back into the city. Throughout the war it served over 250,000 servicemen with refreshments. It also provided 1,800 servicemen who had missed trains, with overnight beds. (HDM 11/05/1918). Today, you can view 20 memorial plaques in the entrance to the station honouring more than 2,000 men who fought during the First World War from Hull.

St Johns Voluntary Aid Detachment Hospital

This hospital was based at the Newland School for Girls on Cottingham Road, Hull. It was staffed by Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurses and opened by Field Marshall French in April 1917. It was run by Lady Majorie Nunburnholme and one of the largest hospitals in the country. It was also highly regarded by many military and Naval Authorities.

The VAD’s of Hull also gave First Aid in different parts of the City. The Hospital held regular concerts and auctions, to entertain patients and raise funds (HDM 20/07/1917). The Hospital even arranged a cricket match in Withernsea, which raised £60 (HDM 21/08/1918). The Hull VAD Hospital, at Cottingham Road, cost £23,481, of which £15,000 was raised by donations and £5,000 received by Military and Naval Grants. Total expenditure was £18,275, provisions cost over £5,000 and equipment was £8,745 (HDM 12/02/1918)

It may well have been made as a Christmas present for a nurse as a gratitude of thanks?

It is engraved: S T. John V.A.D. Hospital, Hull, Xmas 1918.

It measures 58mm x 38mm x 20mm.

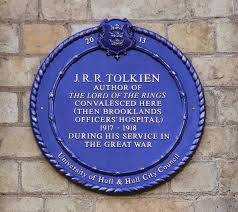

‘Brookland’s Officers Hospital’

This is now the ‘Dennison Centre’ on Cottingham Road, and opened in early 1917. This hospital was run by the East Riding Branch of the Red Cross society and was commanded by Mrs Strickland Constable. JRR Tolkein spent 18 months there convalescing from ‘trench fever’. It is said that he was inspired by the surroundings to later write ‘The Lord of the Rings’. These military hospitals were manned and operated by the Royal Army Medical Corps and Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, supplemented by voluntary workers from a number of organizations, including the Voluntary Aid Detachments, Red Cross, St John’s Ambulance and YMCA.

Hull established a number of complimentary Charities during the war. These included the Hull and East Riding Fund, for the needs of local units and prisoners of war (headquarters at Peel House, 150 Spring Bank, Hull); Hull Social Club for Soldier’s and Sailor Wives, Mason Street, Hull; The Lord Mayor’s Local War Relief Fund; Hull District War Refugees (Belgian refugees); Interned Hull Seaman’s War Charities (to provide necessities and comforts for merchant seaman, interned in enemy territory); Hull Patriotic Fund for widows of soldiers and sailors, and the Hull Great War Civic Trust in 1918, to help Hull’s wounded and their Dependents; Hull Bread Fund, based at Freehold Street, Hull, to supply English Prisoners of War: The Hull & Barnsley War District Relief Fund, to assist dependents of their railway staff serving.

In addition, other great work was done in Hull by local organisations, charities and trade unions and individuals. The ‘Blind Institute’ on Beverley Road was used to rehabilitate those with sight impairments. The De La Pole hospital at Castle Hill cared for ‘shell shock’ victims. Peel House, at No: 150 Spring Bank, became a centre for ‘Hull’s Prisoner of War Fund‘, producing 130,000, life saving, ‘Red Cross’ parcels, for prisoners of war. Hull’s Seaman’s Union also sent parcels, as well as providing money, clothes and coal for those in need at home. The Hull Soldier’s Club, based at Beverley Road Baths, reputed by soldiers, to be one of the best in the country. The Hull District War Refugee’s Committee, for Belgian Refugees, was set up on the 7th September 1914, at Bowalley Lane, Hull. Of its 500 volunteer helpers, 400 were women aiding a total of 1,200 refugees. Th Hull Flag Appeal for prisoners of war, raised £1,500 (HDM 04/08/1917). The East Hull Working Party, formed in August 1914, repaired and sewed 5,690 articles for servicemen during the war and made 470 clothing articles for patients at the VAD Hospital, on Cottingham Road (HDM 18/11/1918). The Mother Humber Memorial Fund, based at 22 Whitefriargate, Hull, was a fore runner of the modern “Food Banks” and distributed groceries to urgent cases of illness and poverty (HDM 12/01/1920).

In October 1918, Hull also established a “Comrades of the Great War“, Bureau, at 41 George Street, Hull. This kept discharged servicemen in touch with local employers, Trade Unions, Employment Exchanges, and Advisory Committees, dealing with employment and pensions. This organisation was additional to the National Federation of Discharged soldiers and Servicemen. Hull also established one of the Country’s 363 ‘National Kitchens‘, in Porter Street, Hull, These were created by the Government to feed people during World War One. These improved diets, cut down food waste and proved hugely popular. The Hull menu for example, showed a bowl of soup, a joint of meat and a portion of side vegetables cost 6d – just over £1 in today’s money. Puddings, scones and cakes could be bought for as little as 1d (about 18p). These self-service restaurants, run by local workers and partly funded by government grants, offered simple meals at subsidised prices. A 1918 ‘Scarborough Post’ story about the National Kitchen in Hull emphasised the ambition of the typical urban outlet: “The place has the appearance of being a prosperous confectionery and cafe business. The business done is enormous.”

It is also most appropriate to mention the fine work of Dr. Mary Murdoch, the first women medical practitioner to work in Hull. She had been connected with the Victoria Hospital for Sick Children in Park Street, since 1892. and had done much to promote the health and welfare of women and children in Hull. In 1910 Mary Murdoch became a Senior Physician, Hull’s first GP, and served as a medical representative on a number of Health Committees. She worked tirelessly to help the sick and wounded since the outbreak of the war. Unfortunately, Dr Mary Murdoch died after a short illness in March 1916. She had escaped a Zeppelin air raid, by running in the snow and was to catch a chill which became fatal. She had raised £250 to reopen the babies hospital at the Victoria hospital in Park Street, and after her death left £962 to the same cause and endowed a cot in her name.

It is also most appropriate to mention the fine work of Dr. Mary Murdoch, the first women medical practitioner to work in Hull. She had been connected with the Victoria Hospital for Sick Children in Park Street, since 1892. and had done much to promote the health and welfare of women and children in Hull. In 1910 Mary Murdoch became a Senior Physician, Hull’s first GP, and served as a medical representative on a number of Health Committees. She worked tirelessly to help the sick and wounded since the outbreak of the war. Unfortunately, Dr Mary Murdoch died after a short illness in March 1916. She had escaped a Zeppelin air raid, by running in the snow and was to catch a chill which became fatal. She had raised £250 to reopen the babies hospital at the Victoria hospital in Park Street, and after her death left £962 to the same cause and endowed a cot in her name.

WWI helped hasten many medical advances. Physicians learned better wound management and the setting of bones. Harold Gillies, an English doctor, pioneered skin graft surgery. Geoffrey Keynes, a surgeon from Britain, designed a portable blood transfusion kit. It saved thousands of lives during World War 1. The huge scale of those who needed medical care in WWI helped teach physicians and nurses the advantages of specialisation and professional management. ‘X’ rays were used by the military for the first time during the war. Blood transfusions became routine to save soldiers, with the first blood bank established on the front line in 1917.