Hull has been a port since medieval times. It was founded over 900 years ago, by Monks from Meaux Abbey, who used the deep, wide, Humber, to trade wool into Europe. Hull was recognised as a trading city by King William and became Kingston Upon Hull in 1299. Hull has since had a long and varied history and is the place best known for abolishing slavery and where the English Civil war began. However, it was not until the commercial boom in the 1830’s, that Hull began to expand from a small town to a modern City. As sail power gave way to steam power, Hull extended trade links throughout the world. New docks were opened to serve the frozen meet trade of Australia, New Zealand and South America. Parallel to this was the growth of passenger shipping, which Hull monopolized. The Wilson Shipping line of Hull, with over 100 ships became the largest private fleet, sailing to different parts of the globe.

Hull grew from 12,000 houses in 1831, to 20,000 houses, in 1861, then 49,387 houses (1891), 53,398, (1895) and 60,237 houses in 1906, with the growth occurring primarily outside of the Old Town. At the same time many inner city slums were cleared, providing recreational parks and more business opportunities. With this, Hull’s population grew from 22,161, in 1801; to 84,690, (1851); 236,772 (1901) and then to 291,118 people in 1914, with most people living around the city centre and docks. 1914 Maps show few houses west of Carlton Street, on Hessle Road. West of Wheeler Street, Hawthorne Avenue, Alliance Avenue and Exmouth Street were open fields, brickyards, and railway lines. North of Cottingham Road and Clough Road, was mostly countryside. There were just a few streets around St Johns Church with Wellesley Avenue being on the outskirts of Hull. The further development east of Hull was Portobello Street and New Bridge Road, but even these were interspersed with allotments, fields and farms. What we know as Bransholme, Ings, Longhill and Greatfield were farms. Bilton, Marfleet and Preston were separate villages. By the time of the First World War, the majority of Hull’s 300,000 people, which was larger than it is today, lived in squalid conditions. Over 80% of the 66,090 Hull homes, in 1914, were classified as ‘working class’ type, with a rent not exceeding £26 per year. Only 28,400 Hull homes were regarded as satisfactory, with adequate light and air circulation and having a yard or garden at the rear with a secondary means of access. Some 21,800 Hull properties, mostly ‘terrace’ type housing were unsatisfactory, built at a high density of 60 houses per acre, compared with an average of 7 houses to the acre for the City as a whole. They included 2,800 ‘slum houses’ which were old, damp, poorly built and situated in congested districts. Tenants invariably shared a single tap and outside toilets, which were situated together in a communal courtyard. Over 98% of Hull people rented their homes rather than owned them. The homes were largely poor and basic, with little choice, but the rents were cheap. People preferred to live near their place of work and not commute long distances. With no Welfare state and few Council houses, people preferred to live in tightly knit communities, where they could support each other or have access to shops and facilities. For the few and wealthy, home ownership outside the city centre, was the most desired and affordable option. Hull newspapers in 1914, advertise a 3 bed house for sale in Anlaby Park for £415 – £435, and 4 bed houses for between £529 – £550. After the war, a typical 3 bed, semi-detached house, sold for between £540 – £740.

Population growth and overcrowding brought problems of disease and poverty. July, August and September 1849 saw cholera rapidly spread through the city, eventually claiming more than 1,860 victims. Between Feb and March 1895 – ‘The Distress in Hull’ lasted two months during which tea and soup were provided to 12,147 poor children by the Police Fire Brigade. On 10 January, 1901 the SS Friary arrived in Hull from Alexandria. One dead man was buried, but then seven crew members, a medical attendant and a watchman, all developed the plague. Seven of them died. Between June 1918 and May 1919 influenza killed 1,261 people in Hull. In one five-week period 684 people died.

There was high infant mortality in Hull. Infants had perhaps a 1 in 3 chance of surviving their first years, then maybe a 1 in 3 chance of reaching 5 years old. Poor diet, housing and sanitary conditions, and overcrowding meant diseases spread quickly. Infants from working class families were most at risk. Whooping cough, diphtheria and scarlet fever were then killer diseases. In 1881-82, scarlet fever killed 682 children in Hull, the highest figure in the country.

The foundations of modern Hull, were laid during a 80 year period before the First World war. A rapid development timeline, shows Hull’s first police force established (1836); the start of the Hull to Selby railway (1840); the start of the Thomas Wilson Shipping line (1841); the building of the Railway Dock (1846); Victoria Dock (1850); The Hull and Holderness Railway (1854); the creation of Pearson Park, (1860); The Hull School of Art (1861); Londesborough Barracks (1864); the founding of Hull FC Rugby Club (1865), the building of Hull Town Hall (1866); the completion of Albert Dock (1869); Hull Prison (1870); William Wright Dock (1873); Hull Trams (1875); Hull Botanic Gardens (1880); Hull Philharmonic Society (1881); Hull Kingston Rovers Rugby (1882); St Andrews Dock (1883); The Hull and Barnsley Railway and Alexandra Dock (1885); the Hull Daily Mail established (1885); Hull’s first Synagogue (1886), the building of East Park (1887); County Borough status (1888); the Boulevard Stadium (1895); Hull Cricket Circle (1898); Hull City status (1897); The opening of King Edward Street and Jameson Street (15 Oct 1901); Hull Telephone exchange (1902); the opening of an electric tramway on Hedon Road (17 Dec 1903); Hull City Football Club founded (1904); Beverley Road baths, opened 29 May 1905); the Wilberforce Museum (1906); Riverside Quay (1907); the building of Hull City Hall (1909); the first Theatre De Luxe (1911); King George Dock (1914), Hull’s first cinema, The (Tower) Pavilion Picture Palace (1915) and the Councils Guildhall and law courts, also completed in 1915.

Hull was at its peak of prosperity when the First World War began. It was Britain’s third largest Port. The King George V Dock, completed at Hull, in 1914, was Britain’s, most modern port. Hull was a major exporter of coal and importer of timber. Hull was the seed crushing capital of Britain. It was a major producer of oil and lubricants and manufacturer of cake feed for cattle. Hull had built England’s, first ferro-concrete factory, at Rose Down and Thompson, in 1900, and Britain’s, first ferro concrete bridge across the River Hull, in 1902. Electric cables laid from the Humber Dock, created Britain’s first electric powered factories along Wincolmlee. Hull industries patented and built new machinery for the world, creating a boom in small manufacturing and ship building. By 1914, Hull had Britain’s largest fishing fleet with the most modern trawlers. It was home to the Wilson Shipping Line, Britain’s largest passenger fleet. The Hull born shipping magnet, Sir John Ellerman, was the richest man in Britain. The City’s population of nearly 300,000 was the highest it had ever been. However, the start of WW1 would bring this growth to a dramatic halt. 15% of Hull’s trade was with Germany and this ended overnight. Many Hull’s ship were stranded and interned in enemy ports. Hull’s fishing fleets were requisitioned by the Admiralty, all fish and chips shops were closed during WW1 and hundreds of Hull ships would be lost in the war. The fear of invasion and Zeppelin raids stunted investment. Coal exports and industry were moved away from the City. Over, 70,000 Hull men enlisted for war service and the City’s male population would shrink by 45,000 during the war.

Edwardian Britain

Only 1% of Edwardian’s owned property. Most worked in dark, noisy factories, cut hay in fields, toiled down dirty and dangerous mines; had bones bent by rickets and lungs racked by tuberculosis. Life expectancy then was 49 years for a man and 53 years for a woman, compared with 79 and 82 years today. People lived mostly in back to back tenements or jerry-built terraces, wore cloth caps or bonnets (rather than boaters, bowlers and toppers) and many had never taken a holiday – beyond a day trip to the seaside – in their entire lives.

1914 Britain

Very few envisaged the upheavals that were to come when the year began. August 1914, was one of warmest Summers on record and everyone basked in the sunshine, expecting an idyllic future of peace, progress and prosperity. There had not been a war in Europe for over 50 years. Many of Queen Victoria’s children had married into the worlds dynasties, cementing nations and royal families together. Diplomatic relations between countries were mostly cordial and improving, even between France and Germany after the Franco Prussian war. Globalisation had never been greater. There was a free flow of Capital, goods and people. Economic and financial interdependence made the the thought of war impractical. Nations were becoming consumers rather than warriors, enjoying the benefits of innovation, and industrialisation, with mass produced goods and services. Those that could afford to, could travel the world, without a passport and live anywhere, how they liked, without permission from the state and free from the bureaucracy faced today. The prospects of a world war seemed inconceivable. Few foresaw that the assignation of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Serbia, on 28th June 1914, would trigger a series of rival military alliances and force Britain into war just 35 days later.

The biggest troubles Britain faced were domestic and not international. The Liberal government of the day was under attack from all sides. The government plans to grant “Home Rule” to Ireland were being fiercely resisted by Ulster Unionists in the north, who had support from within the upper ranks of the British Army, as well as from the opposition Conservatives. In March 1914, the news that the government had military plans to put down a possible rebellion in Ulster led to the resignation of 57 Army officers, and the so-called Curragh Mutiny. More than a quarter of a million defiant Ulstermen signed a Covenant, pledging to use “all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a home rule parliament in Ireland”. The Catholics of the south were armed and organised to match the Protestants of the North.

Ireland wasn’t the only crisis that prime minister Herbert Asquith faced in 1914. The Suffragettes, fighting for votes for women, were intensifying their campaign. In March 1914, Mary Richardson, slashed the Velasquez painting the Rokeby Venus at the National Gallery in London. In April, a Suffragette armed with a hatchet, broke ten large panes of glass in a cabinet at the British Museum. Across the country Suffragettes set fire to empty houses and railway stations, piers and sports pavilions and vandalised golf courses. In June they were thought to be behind a bomb exploding in Westminster Abbey, damaging the Coronation Chair.

Ireland wasn’t the only crisis that prime minister Herbert Asquith faced in 1914. The Suffragettes, fighting for votes for women, were intensifying their campaign. In March 1914, Mary Richardson, slashed the Velasquez painting the Rokeby Venus at the National Gallery in London. In April, a Suffragette armed with a hatchet, broke ten large panes of glass in a cabinet at the British Museum. Across the country Suffragettes set fire to empty houses and railway stations, piers and sports pavilions and vandalised golf courses. In June they were thought to be behind a bomb exploding in Westminster Abbey, damaging the Coronation Chair.

The government was faced with a renewed challenge from Trade Unions. The years leading up to the First World War saw much industrial discontent with widespread strikes. On 23 Jun 1911 – there were Strikes by Hull seamen, firemen, dock labourers, coal heavers, lightermen, and flour millers; Between 18-24 Aug 1911 – Hull Railway employees’ went on strike. On 10 Oct 1911, Hull’s Oil millers’ went on strike; 1914 began with a lock-out of London bricklayers by their employers. Trade union membership had reached four million and a triple alliance of miners, railway workers and port workers, was forming with plans for a general strike.

As spring turned to summer, the idea that Britain would be soon embroiled in a world war, seemed far-fetched. There had been wars in the Balkans in 1912 and 1913, but they had not led to the involvement of Britain, so why would 1914 be any different? While the rise of Germany had caused some trepidation and several books and plays warning of the dangers of a German invasion had been published, the threat did not seem immediate. Even after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie, by Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip, in Sarajevo, on June 28, the British government did not even meet to discuss foreign affairs until 24th July 1914. The Irish crisis seemed far more pressing. While some ministers were concerned about the prospect of a European war, Asquith wrote in his diary: “There seems to be no reason why we should be anything more than spectators.” However, on 4th August 1914 Germany invaded Belgium and Britain declared war. Few could have imagined that the conflict would still be raging four years later. For a while it was a case of “business as usual” and life carried on as normal. Cricket continued with Jack Hobbs leading Surrey to their first County Championship. The Football Association decided to play on too, as did the horse racing authorities. Contemporary newspapers show people continued to browse dress patterns, plan weekend drives, tear out recipes, queue for cinemas, oblivious to what was going on. It was only as 1914 dragged on and the deadlock in France and Belgium became obvious, that people realised, that Britain was involved in a world conflict, that was going to last much longer than a few months. As patriotic fervour swept the country those who had been fighting the government in the first half of 1914, halted their campaigns. At the outbreak of war, trade union leaders proclaimed an industrial truce. Suffragette leader, Emmeline Pankhurst, urged her followers to support the war effort. Ulster Unionists who had threatened rebellion, enlisted, along with their Irish nationalist opponents, to fight alongside each other in the British Army. The domestic battles of early 1914 had been replaced by life-or-death battles in the mud of northern Europe.

Middle Class Homes in 1914

Middle Class Homes in 1914

In 1914, only about 20% of the population of Britain was middle class. (To be considered middle class, you would normally need to have at least one servant). In 1914, well off people lived in very comfortable houses. However, to us today, ‘middle class’ homes would seem overcrowded with furniture, ornaments and nick-knacks. Gas fires became common in the 1880’s. Gas cookers became common in the 1890’s. The electric light bulb was invented in 1879. By 1914, most towns had electric street lights, but, at first, domestic electric lighting was expensive. In 1914, the majority of middle class families, still used gas for lighting their homes. By 1914 middle class people in Britain usually had bathrooms. The water was heated by gas.

Middle Class Leisure in 1914

Middle class people played games, like lawn tennis and snooker. Board games like snakes and ladders and ludo were also popular. In 1914, bicycling was a popular sport. The safety bicycle went on sale in 1885. Bicycling clubs became common. Reading was also popular in 1914. The first Sherlock Holmes story A Study in Scarlet was published in 1887 by Arthur Conan Doyle. A new form of writing, was science fiction, pioneered by men like H G Wells. Crosswords which had been been invented in 1913, by Arthur Wynne, became a craze. The first dress patterns were launched in 1914 inspiring new fashions and designs. Mary Phelps Jacob had just invented the first bra. Women were abandoning the corset for more free flowing clothes, and newspapers remarked that women were now seen in public without wearing hats! Tinned food and cookery books were all the rage. The new century introduced commodities, such as tinned food, Bisto gravy, Heinz baked beans and Bird’s custard, with new “Ice Closets” to put food in. Food could be shipped from distant corners of the world and chains of high street grocery stores were replacing small specialist tradesmen. Previously, a cook’s life was ruled by Mrs Beeton and Alexis Soyer, seasonal food and a lack of refrigeration. Now there were new publications like ‘Hints and Recipes for Cooking Today’, ‘The Atora Book of Olde Time Christmas Recipes’, ‘Kitchen Essays’, and ‘The Importance of Eating Potatoes’. These were all designed to educate a new breed of woman who, owing to economic privations, was having to go it alone in the kitchen, often without the benefit of cook or scullery maid.

Britain’s middle classes were very fond of the theatre. The cinema was still a relatively new pastime, and films were without sound and in black and white. Around 1910, cinemas were built in many towns. In February 1914, Charlie Chaplin made his film debut in the silent comedy ‘Making A Living’. In April 1914, George Bernard Shaw’s play. ‘Pygmalion‘ opened to rave reviews. Among the notable books, were James Joyce’s ‘Dubliners‘, ‘Tarzan Of The Apes‘ by Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert Tressel’s ‘The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists’. In 1914, going to the seaside, was very popular with those who could afford it. Meanwhile, the first cheap camera was invented in 1888, by George Eastman. Afterwards photography became a popular hobby. In 1914, middle class children had plenty of toys. They played with wood or porcelain dolls, and toys, like Noah’s Ark, with wooden animals. Poor children did not have any toys. Plasticine was invented in 1897 by William Harbutt. It was first made commercially in 1900. Also in 1900, Frank Hornby invented a toy called “Meccano”.

The Working Class in 1914

For the working class in 1914, life was hard and terrible poverty was common. However, life was improving and certain reforms were introduced around that time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, surveys showed that 25% of the population of Britain were living in poverty. They found that at least 15% were living at subsistence level, in other words, they had just enough money for food, rent, fuel and clothes. They could not afford ‘luxuries’, such as newspapers, sweets or public transport. About 10% were living in ‘below subsistence’ level and could not afford an adequate diet.

Surveys found that the main cause of poverty was low wages. The principle cause of ‘extreme’ poverty was the loss of the main breadwinner. If dad was dead, ill or unemployed, it was a disaster. Mum might get a job, but women were paid much lower wages than men.

Surveys also found that poverty tended to go in a cycle. Working class people might live in poverty when they were children, but things usually improved when they left work and found a job. However, when they married and had children things would take a turn for the worse. Their wages might be enough to support a single man comfortably, but not enough to support a wife and children too. However, when the children grew old enough to work, things would improve again. Finally, when he was old, a worker might find it hard to find work, except the most low paid kind and be driven into poverty again.

A Liberal government was elected in 1906 and they made some welfare reforms. From that year, poor children were given free school meals. In January 1909, the first old age pensions were paid. They were hardly generous – only 5 shillings a week, which was a paltry sum even in those days and they were only paid to people over 70 years old. Nevertheless it was a start.

Also in 1909, the government formed wages councils. In those days some people worked in the so-called ‘sweated industries’, such as making clothes and they were very poorly paid and had to work extremely long hours just to survive. The wages councils set minimum pay levels for certain industries.

In 1910, the first labour exchanges, where jobs were advertised, were set up. The economy was relatively stable in the years 1900-1914 and unemployment was fairly low.

In 1911, the government passed an act, establishing sickness benefits for workers. The act also provided unemployment benefit for workers in certain trades, such as shipbuilding, where periods of unemployment were common. Meanwhile the workers had formed powerful trade unions.

Working Class Homes in 1914

In 1914, a typical working class family, lived in a ‘two up, two down’. They had two rooms downstairs and two upstairs. The downstairs front room was kept for best. The family kept their best furniture and ornaments in this room. They spent most of the their time in the downstairs, back room, which served as a kitchen and living room. In 1914, working class homes were lit by gas. Most working class homes had outside lavatories. From about 1900, some houses were built for skilled workers, with bathrooms and inside toilets. However, they were still rare in 1914. Moreover, very poor families sometimes lived in just one room.

Life expectancy was low. Often parents could not afford medical treatment for their children and hospitals were basic and few. Whooping cough, diphtheria and scarlet fever were common killer diseases. Infants from working class families were most at risk. Children who survived these diseases continued to suffer from dental decay, ear and eye infections, rickets, head lice, pneumonia, bronchitis and undernourishment. They were small in height and usually underweight.

Children were still treated much the same as adults. In 1900 children were able to smoke, drink and gamble and often went into pubs, with their parents. Children were also responsible for any crime they committed and were punished and put in prison like adults. It was not until the ‘Children’s Charter’, an Act of Parliament in 1908 that juvenile courts were established to treat children under 14 years as children. It became illegal to sell tobacco or alcohol to those under 14. After 1908, children were sent to special Reform Schools rather than prison and had to stay in school until they were 14.

Food in 1914

Food was expensive in 1914. Some working class families, typically sat down to a tea, of a plate of potatoes and malnutrition was common among poor children. In 1914, a working class family spent about 60% of their income on food. Sweets were a luxury in 1914. However, for those who could afford it, new types of biscuit were available. The Digestive was invented in 1892. Custard creams were invented in 1908 and Bourbons were invented in 1910. Bread was the staple food for most of Hull’s population. Bread made from wheat was expensive, so people ate barley and rye bread. In years of bad harvest as in the late 18th century, high grain prices caused terrible hardship and starvation. Potatoes replaced bread as the staple food in the 19th century. Meat such as beef, mutton, pork, game and poultry, could be afforded by the wealthy and eaten regularly. The poorest in Hull would have gone without. River and sea fish were eaten fresh, salted or dried, and traditionally eaten on a Friday. Many of the vegetables grown today, – parsnips, broccoli, or artichokes were used in the 17th Century. At the time, people were suspicious of raw vegetables and fruit and tomatoes did not become popular until the 20th century.

Transport in 1914

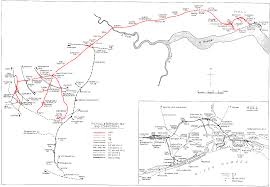

In 1914, railways were the main form of overland transport. Cars were very rare, although number plates were introduced in 1903. The same year a 20 MPH speed limit was introduced. Most towns had electric trams. In many towns by 1914, there were also motor buses and Hull had it’s own tram system. Below is a picture of the Botanic Station, Spring Bank, Hull. During ww1 train fares increased dramatically.

Working Class Leisure in 1914

In 1914, the average working week in Britain was 54 hours. By then, many people only worked half a day on Saturday. Skilled workers often had paid holidays, but most people only had bank holidays. Nevertheless, the working class were starting to have more leisure time and football matches became a popular pastime. Many towns had free public libraries. Newspapers also became much more common. The Daily Mail was first published in 1896, The Daily Express was first published in 1900 and the Daily Mirror began publication in 1903. By 1914 life expectancy in Britain was about 50 for a man and about 54 for a woman.

Hull’s Trade, Docks, and Industry

Hull continued to be an important port in the later middle ages. It exported lead and grain as well as wool. Imports included cloth from the Netherlands, iron-ore from Sweden, oil seed from the Baltic and timber from Riga and Norway. Timber and oil seed continue to be major imports through the port of Hull to the present day.

Hull continued to be an important port in the later middle ages. It exported lead and grain as well as wool. Imports included cloth from the Netherlands, iron-ore from Sweden, oil seed from the Baltic and timber from Riga and Norway. Timber and oil seed continue to be major imports through the port of Hull to the present day.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, Hull’s earliest “industries” included making bricks, burning lime and milling corn. Metal, leather and textile manufacture, and flax, rape seed and sugar processing continued on a small scale in the 17th century.

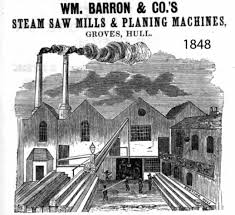

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Hull’s industries grew to become important to the wealth of the city. An 1811 map records eleven corn mills, two sugar houses, two oil mills, a whiting mill, two lead mills, a glue factory, soapery, foundry, engine-maker’s, six roperies, sailmakers and wool spinners. The growth in trade during the 18th century, meant overcrowding in the river Hull and led to the building of Britain’s first inland dock in Hull in 1778. The expansion in trading and fishing during the 19th century meant new docks had to be built up to the First World war. Merchant shipping moved continually further into the East Hull docks.

Domestic trading had been established at Hull’s market Place in 1293, and was vital to everybody for food and household goods. The market place was enlarged during the 18th and 19th centuries and the present indoor marker hall was built in 1904.

Hull’s annual Fair started in the 13th century and like the marker place was a time to buy and sell animals and goods. From 1598, Hull Fair lasted for 16 days, from 16th September when horses, cattle, sheep and small wares, such as pewter, shoes and linen were brought and sold. The nature of Hull Fair has since changed completely and is now a huge ‘funfair’

In the 19th century, Hull’s industry was diverse: shipping, shipbuilding, oil milling, paint making, fishing and cotton spinning were all major employers. Between 1815-1825, Hull became the largest whaling port in the world, with 67 vessels and 2,000 men employed in the industry. The discovery of the “silver Pits” fishing ground, only 50 miles from Hull, meant the first trawlers moved to Hull from Ramsgate and Brixham in 1845. The number of fishing smacks increased from 29 in 1845, to about 270, in 1863, and increased further, helped by the introduction of ice to preserve fish on board. In 1913, there were 389 steam trawlers registered in Hull, 230 were operated by just four firms, Red Cross, great Northern, Gamecock and Hellyers and Co. There were far more people who worked on shore in the fishing industry than went to sea. Those employed in the fishing industry lived in the Hessle Road area of west Hull, near the fish landing docks, and developed a distinctive way of life and community spirit.

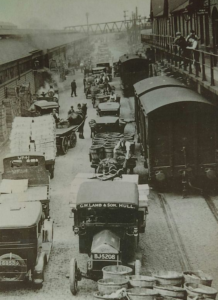

The port after 1840, required railway workers, barge and lightermen, ship chandler’s, shipping clerks, leather workers, tanners, and brewers. Hull industry had many jobs which were either seasonal or casual, or uncertain in their prospects. There was also less work for women and children than in other cities. Domestic service was the main source of income. In Hull, in 1881, there were 9,500 servants, of which 8,400 were women (nearly 90%)

The rapid growth in the scale of industry reflected similar developments in the country as a whole. New industries were accompanied by changes in transport, overseas trade, agriculture, and banking, which had a profound effect on the way people lived and worked. The first bank to open a branch on Hessle Road was the Hull Savings Bank in 1891. The Hull Co-Op opened its first store on the corner of Wassand street, in 1890, and a more successful branch on Wilton Street, Holderness Road and became a Co-operative stronghold, sharing profits out among its members.

Hull was probably at its most prosperous at the start of the First World War. This was reflected in the restoration of Holy Trinity church in 1907, the building of Hull City Hall in 1909, and the Municipal Guildhall between 1904 -1916. While Hull’s whaling industry, declined in the 1860’s, it was soon replaced by a booming fishing and ship building industry. This period of great prosperity was enhanced by the discovery of the fish rich, ‘silver pits’ in the North Sea and new fishing methods, such as the ‘trawl’. The development of steam powered trawlers, also enabled Hull fishermen to fish as far a field as Iceland and the White Sea. Many other Hull industries developed in the 19th Century, using imported raw materials, through its ports. These included corn milling, seed crushing, paint making and cotton weaving.

From 1800 -1900, Hull’s population increased ten times from 22,000 in 1801, to over 290,000 by 1914. New industries grew around imported commodities, such as timber, wheat, soya beans and seeds for the oil crushing industries. The first reference to milling rape seed for oil in Hull was in 1525, and the Oil Milling industry was well developed by the mid 18th Century. During the 19th century, seed crush for oil became a large scale industry, employing some 1,500 people in 1893. In 1889 there were 23 oil refiners listed. British Oil and Cake Mills was formed in Hull in 1899.

Hull was known for Flour Milling and its milling of corn as early as the 14th Century. By 1858 Hull had 18 corn millers, most of whom were employed in grinding locaaly grown corn in windmills. From 1887, with the establishment of the purpose built St Andrews Fish Dock, on Hessle Road, Hull became the biggest fishing port in the British Empire and provided food and materials for a third of Britain.

On the 26th June 1914 King George V opened the ‘King George Dock’, which completed the port complex and confirmed Hull as the third largest port in England, surpassed only by Liverpool and London. some of Hull’s largest employers were:-

- Needlers Ltd: In 1856, Fred Needler started making sweets in Anne Street, Hull, employing three members of staff. As business increased the firm moved in 1890 to Brook Street and later to a larger building in Spring Street, Hull. By 1906, the workforce numbered 50 and a new factory was built at Sculcoates Lane. The same year the company name, which had originally been Fred Needler’s Confectionary Works was changed to Needler’s Ltd. The Needler’s sweet factory, was spacious and well equipped. It employed 1,700 workers, mostly women, to make confectionaries and ‘Military Mints’ for soldiers at the front. Like many other family firms, Needler’s took an interest in the welfare of their workers, with a profit sharing scheme, and in 1916 a Social Welfare Department. The Needler family continued to be active in the firm until 1986, when the business was acquired by a holding company.

Needler’s Sweet Factory, Bournemouth Street, Sculcoates Lane, Hull - – Fenner’s:

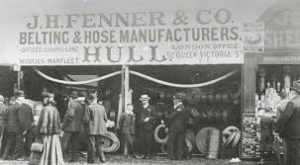

The Fenner Group was founded in 1861 by Joseph Henry Fenner and located at 21½ Bishop Lane in Hull, England. Subsequently, the Company moved to Marfleet, at that time a small village outside Hull.

The Fenner Group was founded in 1861 by Joseph Henry Fenner and located at 21½ Bishop Lane in Hull, England. Subsequently, the Company moved to Marfleet, at that time a small village outside Hull.

Joseph Henry Fenner The early products manufactured were leather belting for use in power transmission, lacing and hoses, including fire hoses. By the 1890s, the Company was exporting its products widely across Europe and into India and the Far East. When Joseph Henry Fenner died in 1886, his son Henry John Fenner, managed the company. His son, John Prebble Fenner, was apprenticed as a leather belting manufacturer served as a Second Lieutenant in the 7th East Yorkshire and was killed on 8 Aug 1916. In 1913, immediately prior to the First World War, export markets accounted for over 70 per cent of sales. The loss of many of these markets during the war forced the Company to focus on domestic opportunities after the war was over. In the 1920s and 1930s, Fenner made many technological developments and, during this period, Fenner first established its technical leadership in textiles, particularly as reinforcements for rubber products.

– Rank Hovis McDougal:

- founded by Joseph Rank in 1875. He built a mechanically-driven flour mill in Hull in 1885, becoming one of the

largest flour producers in the world.) Joseph Rank Ltd, of Clarence Street, employed

- nearly 3,000 women in flour production during the war, and Joseph Rank himself was asked to join the Wheat Control Board due to National food shortages

- Reckitt & Sons: (Reckitt’s founded by Isaac Reckitt in Hull in 1840. He became a major producer of health, hygiene and home products, such as blue washing powder, (1879), “Brasso” metal polish (1905), shoe polish (1913) and later “Windolene” and Dettol”. After his death in 1862, the business passed to his three sons. The company had three factory sites at Dansom Lane, Morely street and Stoneferry Road. Reckitts expanded at the outbreak of the war by buying two German companies based in England – Rawlins & Son and the Global Metal Polish Company. They employed 4,761 in 1915, which rose 5,609 in 1917. By the Armistice 1,100 Reckitt’s employees were serving in the armed forces and 153 had lost their lives. Being Quakers, Reckitt’s factories, produced non combative war goods, such as cleaning materials, gas masks, and petrol cans. They provided a number of facilities and welfare schemes for their employees, such as health care, evening classes and pensions, and in 1908 opened “Garden Village”, a housing estate off Holderness Road, for employees. In the 1920’s Reckitt and JJ Coleman merged their overseas trade and in 1954 they merged fully as Reckitt and Coleman. Today Reckitt and Coleman are still Hull based and a major employer. Hull remains a centre of the pharmaceutical industry.

-

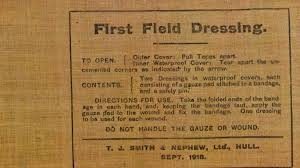

- Smith & Nephew: In 1856 Thomas James Smith opened a small chemist shop in Whitefriargate, Hull, and supplied hospitals with cod liver oil. From this developed the firm of Smith and Nephew, when his nephew, Nelson Smith became a partner in 1896. On his death in 1896, another nephew, Horatio Nelson Smith took over the management of the business, and produced multi national medical equipment.

- Smith & Nephews’, built a factory at Neptune Street in Hull. It grew from 50 to 1,200 employees, and supplied field dressings and surgical equipment for the Allies, throughout the war. One particular order, for the French Government, in October 1914, was worth £350,000 (£108 million), and was delivered in just 5 months. A few days after the declaration of World War 1 in 1914, Horatio Nelson Smith (the nephew of the company founder T. J Smith) met with an envoy of the French President in London. The company was awarded a contract to supply £350,000 of surgical and field dressings, to be delivered in five months.Every British soldier carried two field dressings, and with the millions of casualties caused, no doubt Hull helped save many lives.

Hull’s Smith & Nephew provided many WW1 Field Dressings.

- – Wilson Shipping Line: (Founded by Thomas Wilson Sons & Co in 1840, the company operated a relatively large fleet, and was a leading Maritime interest at the time. The Company expanded in 1900 by buying Hull’s Earles ship yard in 1900 for a sum of £170,000. It built steamships, yachts, war ships and ‘knock down’ ships which could be reassembled abroad. It provided vessels for many other British shipping firms, especially those operating on North Sea routes, such as the Great Eastern Railway and the Hull & Netherlands Steamship Company. The Wilson Line, Hull’s largest merchant shipping company, was badly affected by the First World War. It had lost 15 of its 79 ships by 1916, and by the end of the war, over 40 of its 84 vessels and some 300 crew members had been lost in the war. It was eventually sold in 1916 after the loss of three of its largest and most prestigious vessels to enemy action (“Aaro” and “Calypso” sunk ; and the “Eskimo” captured).

- – Fishing Companies. Hull was the home of the great boxer Fleets, such as the Gamecock, Great Northern and the Red Cross Fleets, to the companies of Pickering & Haldane Steam Trawling Co, Kelsall Brothers & Beeching, F&T Ross, Hudson Brothers, Hamlyns, Marrs, Boyd Line, Lord Line and Hellyers. From the early 1840`s, fishermen, boys and vessels came from all corners of the UK to fish from Hull. The Devon Smacks from Brixham and Plymouth, the South East coast smacks of Ramsgate and Gt Yarmouth, to the North East coast smacks from Scarborough and Shields.

Hull Fish Docks – The “Bullnose” – Blundell, Spence & Co: The ready supply of oil from the seed-crushing industry led to paint manufacturing becoming a major industry in Hull in the 19th Century. Blundell’s Paint Works was founded in 1811 as a partnership between former Hull city councillor and Lord Mayor Henry Blundell and his brother-in-law William Spence. The company, Blundell and Spence, manufactured paint in a factory on the corner of Spring Bank and Beverley Road. Still referred to as Blundell’s Corner, this site was once occupied by the Hull Daily Mail. It was one of the leading paint manufacturers and largest employer in Hull. The company was one of the first to introduce a profit sharing scheme for workers. It created new colours, such as ‘Brunswick Green’ and ‘Hull Red’ which was used to paint the keels of ships.

- – Earle’s Cement Company: Brothers George &Thomas Earle established their cement company at Neptune Street, in Hull in 1821. By 1866 it had expanded and moved to a 10 acre site in Wilmington area of East Hull. It served as a significant employer, providing work for several hundred people and by the end of the 19th century it had become one of the premier cement manufacturers in the country. Although it amalgamated in 1912 with other cement companies to form the British Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd., it retained its identity through the marketing of its Pelican brand cement up until 1966, when it subsequently became the Blue Circle Group, which is now part of the Lafarge Cement Company.

Rose Downs and Thompson, based at Cannon Street, Hull, was established in 1777. They invented the Anglo American Presses, which could press large numbers of oil cakes, and in 1870, they became the principal British firm for making oil mill machinery. Most of their customers were the seed-crushing firms. In the 1880’s the company diversified into winches, grab cranes and other pieces of steam machinery for trawl fishing. This move helped them survive a period of debt in the 1880’s and their financial position improved in the 1890s. They became well established engineers, iron founders and manufacturers of oil mill and hydraulic machinery.

In 1910, the firm expanded, buying a gear wheel firm in Leeds and opening branch offices in Shanghai and Hong Kong. In 1914, they were Engineers, Iron Founders and Boiler Makers. They still specialised in Oil Mill machinery, made the Kingston Dredger and employed some 350 people. In 1916, John Campbell Thompson, the chairman, died, but not before the company had converted to munitions making to help with the war effort. By October 1918, Rose, Downs and Thompson, employed 938 workers including 359 women (3 under 18 year old girls) with 212 employees leaving for war service.

Other Trades and Industry There were some 115 major factories in Hull. Of these, 25 were involved in seed crushing and oil cake manufacture, eight in oil extracting and refining, 11 in paint and colour making, three in the manufacture of soap and two in the production of margarine. Grain warehousing was carried out in 10 factories and there were six flour mills. The fishing industry accounted for three premises for cod liver oil extraction and two factories produced fish manure. There were 13 saw mills, four ship yards and six marine and mill engineering works. Other large factories were engaged in the manufacture of starch, blue and black lead (6); tar distilling (2); the making of tin cannisters and paint drums (4); tanning and leather production (3); canvas and sack making (1); and sweets and confectionery (1). In addition to these larger factories, a total of 1,169 workshops were registered with the City Council. The trades with the largest number of workshops were bakers (83), boot repairers (77), cabinet makers (24), coopers (39), cycle repairers (49), dressmakers (118), fish curers (62), tinsmiths (20) and watch and clock makers (27). The largest number of employees in these workshops was in the fish curing trade (407 men and 535 women), with dressmaking second (10 men and 849 women) and tailoring (271 men and 326 women) coming third. Approximately, 700 men and women were employed as outworkers, the vast majority of people being engaged in bespoke tailoring and the making of fish nets. The above details reflect the many facets of life in Hull, suits and dresses made to measure, leather boots and shoes which could be repaired, craftsman-made furniture etc. The number of bicycle repairers also indicated the large number of cycles used in the city, and it was said that only Coventry could match Hull for its number of cyclists. By 1919, there were at least 30 premises in Hull still involved in ‘dirty’ processes, such as tripe boiling (6), cod liver boiling (5), gut scraping (3), fish manure production (3), tanning (3), fat and candle melting (2), soap boiling (2), bone boiling (2). Hull had expanded massively in the 19th and 20th Century, and by 1914, began to look like a modern city. However, although Hull was prosperous, many of its citizens were not, and the City’s population remained relatively poor. Hull’s wealthy families were relatively small in number, compared to Liverpool, Bristol or London, and these families increasingly moved away from Hull, to live in style, outside the City.

Grace’s Guide to Industrial British History http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Main_Page. (Grace’s Guide Ltd is a charity (No.1154342) for the advancement of education of the history of Industry and Engineering in the UK.)

Hull was characterised by dock related work which was temporary and low paid. Over 35% of the population had jobs, such as unloading ships; quayside activities; warehousing and shipyard engineering. Many were unskilled casual workers, often out of work in winter, due to Hull’s trade with the frozen, Baltic Ports. In 1884 it was estimated that 1,000 Hull families were starving in East Hull, resulting in the premature death of many children. The construction of Albert Dock stopped in 1885 because the Hull & Barnsley Railway Company ran out of money. This put 5,000 men, mostly ‘navies’ out of work. Weddings declined, which is usually an indication of hard times, and there were some terrible winters in Hull, which compounded the misery of the poor.

Increasing Population & Overcrowding

Hull’s population increased rapidly – from an estimated 22,000 people in 1801, to 119,500 in 1870. This rose to 186,292 people in 1885 and then 291,118 in 1914. The growing population and increasing competition for work, led to increased poverty for many local residents. Overcrowding was rife.

For example, in 1909, Hull’s Medical Officer, reported that 303 houses registered with the Authority in Hull, provided accommodation for 3,557 persons, and not all this accommodation was occupied. While many new people were arriving in Hull, others left the City and moved abroad. From 1900 onwards, one in twenty British citizens emigrated to the colonies for a better life. In 1912 alone, 300,000 people left Britain, with the majority moving to the United States, Australia and Canada. Conditions were even worse in the surrounding countryside and many agricultural workers, who could afford to, moved to Hull in the hope of a better life.

The influx of this workforce was added to by emigrants from Ireland and the Continent. A plaque in Hull’s Paragon Railway station, commemorates more than 2.2 million people who passed through Hull on their way to America, Canada and South Africa. Over 1,000 emigrants arrived in Hull every day and many decided to stay. The 1891 Census shows 906 German residents living in Hull, many of them pork butchers. The long standing and vibrant Jewish community in Hull was greatly increased by Jews fleeing religious persecution in Russia in 1881.

Poor Housing was one of the major health problems facing the City. In 1914, over 90% of Hull people rented their homes from private landlords and the standard of accommodation was squalid. Many houses were erected with speed on ill-prepared sites to meet the urgent demand for accommodation from a rapidly increasing population. There was almost no accommodation specifically for the elderly, or adapted housing for the disabled and very few homes solely for women. Over 80% of the estimated 66,090 houses in Hull, were of the ‘working class’ type, that is, they were let at a rental not exceeding £26 per year. A typical “sham” four roomed house, consisting of a living room, scullery, two bedrooms and bath, but without hot water, was rented in 1914, at five shillings and sixpence per week clear.

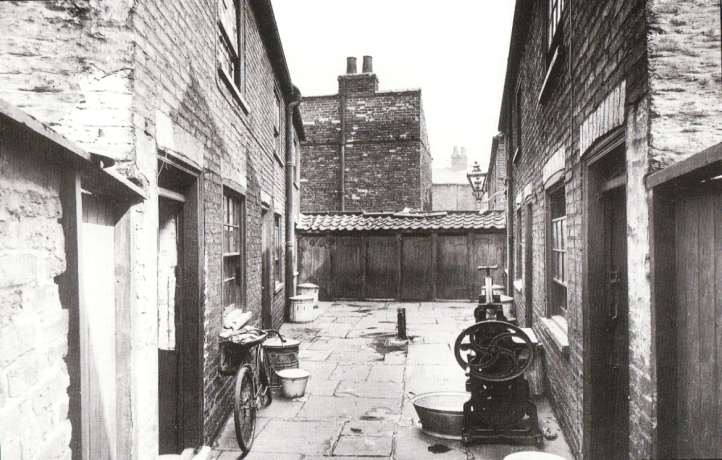

There were some 21,800 ‘Terrace’ type houses deemed unsatisfactory. Many of them were in the older working class neighbourhoods, and were four or five roomed houses, built in terraces. They led off from the main streets, with between ten to thirty houses in each terrace. They were built at a density of about 60 houses to the acre, compared with an average of 7 to the acre, for the City as a whole. The structural conditions within this group of houses varied considerably. Many had rear external walls, of only four and half inches thickness, whilst a very large number were congested at the rear and had no secondary means of access. There were also about, 2,800 slum houses which were old, poor in structure, had similarly thin walls, and mostly were without a damp-proof course. They were situated generally in narrow ‘courts’, in congested districts and were without adequate light and ventilation. The only water tap was usually located in the area of the court and was shared by all the court inhabitants. The sanitary conveniences were also located within the court area and in many cases had to be shared by the occupants of more than one house. There were about 500 houses in Hull which backed on to factories, and therefore had no through ventilation. By 1919, it was estimated that a total of 5,000 new houses were required to meet the arrears which had accumulated during the war years. A further 2,578 were needed to rehouse people living in unhealthy areas and another 200, to rehouse those living in individually unfit houses, in different parts of the City. There were a large number of insanitary cellar dwellings and kitchens. Filth and dirt, was rife and not only infected living conditions, but transmitted illnesses, far beyond their location, through the agency of flies, water supplies and defective drainage. The collection of dry refuse by Hull Corporation did not begin until 1901 and the building of indoor water closets did not start until 1903. By 1912, only 9,881 or 15% of Hull homes had inside toilets. Many houses lacked a rear entrance and occupants had to carry their ‘night soil’ out through the dwelling. By the outbreak of war, there were approximately 300 registered Lodging Houses. These included the Dockers’ Home in Trippett Street, which could accommodate 77 men, in separate ‘cubicles’, and the Salvation Army Lodging House, in Chapel Lane, with bedrooms for up to 130 men. The largest lodging house was Victoria Mansions, in Great Passage Street, which provided separate ‘cubicles’ for 494 working men and had a restaurant and barber’s shop within the building. Some 597 canal boats were also registered as family accommodation. Over 740 homes were recorded as keeping up to 2,850 pigs. The many docks and ships moored in the City Centre at Queens Gardens, meant many Hull houses were plagued by rats and vermin. Few properties had electricity and the smoke from domestic chimneys, factories and coal fired ships polluted the atmosphere. The lack of natural sunlight produced a serious vitamin ‘D’ deficiency in the general population. While Hull had an overcrowded City Centre, the worst living conditions were to be found in Hull’s dock area. Many working class families were crammed into poorly built court houses, often 12 people to a house and different families sharing the same room. These ‘homes’ were old, damp, with insufficient light and ventilation, without back ways and crowded together.

They were uncomfortably hot in summer, bitterly cold in winter and had no direct water supply. Toilets were inadequate and had to be shared by households in the same street. Rubbish stagnated in unpaved streets. The Eastern Daily News published a report in 1883, which compared the streets off Hessle Road, with the ‘foulest slums in Constantinople’. It reported houses “had no furniture and everywhere animals and humans lived together, with sewage flowing from outdoor privies and forming pools in the street.”

Disease

Severe overcrowding and squalid living conditions put Hull’s health at great risk. Outbreaks of diseases, such as small pox, typhus fever, diphtheria and tuberculosis were common. Some, like the Cholera epidemic in Hull in the summer of 1849, lasted 3 months and killed 1,860 out of a population approaching 81,000. Of those who died, 1,738 were recorded as belonging to the ‘labouring classes’ and 40% from the Hessle Road area. By the close of 1871, 23% of Hull children died before the age of one, and 45% died before the age of 12. By 1914, 121 out of the registered 960 Hull births still ended in infant mortality – a rate of 12%. Most children were artificially fed and did not attend infant welfare clinics. They invariably died of diarrhoea, and of ‘rickets’, a disease characterised by poor nutrition, with a softening and deformation of bones. Infant mortality was largely related to improper feeding, poor education, ignorance, negligence and indifference on the part of their guardians. The outbreak of war in 1914 interfered not only with the development of the school health service in Hull, but also with the expansion of services for infants and the pre-school child.

Corruption

Hull’s economic and social problems were often compounded by local corruption. In an age when ‘laissez faire‘ was worshipped in society, it was difficult to expect high standards in public office. Town Councilors were mostly businessmen and amongst some of the worst speculative builders and slum landlords. They probably saw no evil in protecting their business interests and using their special knowledge of the City to make a profit. Thus improvements made at public expense, such as parks, often resulted in higher property rentals and a better environment for them to live in. Even the Police which had been formed in Hull in 1836, were not beyond reproach. Drinking on duty was common and many police officers were frequently charged, with “being helpless with drink while on duty.” In 1885, the Chief Constable of Hull was ‘caught’ with a young prostitute, and forced to resign. He later emigrated to Australia. Crime, lawlessness and prostitution were common in all areas of the town centre. Dog fights were held every Saturday at Stepney Lane, off Beverley Road, which the Police thought better not to interfere with. From 11am, Paragon Street was a “parade of prostitutes, the numbers increasing all day until the night brought drunken fights.” Bookmakers openly took bets on Drypool Green.

The Age of Improvement

The foundations of modern Hull, were laid during a 80 year period before the First World war. A rapid development timeline, shows Hull’s first police force established (1836); the start of the Hull to Selby railway (1840); the start of the Thomas Wilson Shipping line (1841); the building of the Railway Dock (1846); Victoria Dock (1850); The Hull and Holderness Railway (1854); the creation of Pearson Park, (1860); The Hull School of Art (1861); Londesborough Barracks (1864); the founding of Hull FC Rugby Club (1865), the building of Hull Town Hall (1866); the completion of Albert Dock (1869); Hull Prison (1870); William Wright Dock (1873); Hull Trams (1875); Hull Botanic Gardens (1880); Hull Philharmonic Society (1881); Hull Kingston Rovers Rugby (1882); St Andrews Dock (1883); The Hull and Barnsley Railway and Alexandra Dock (1885); the Hull Daily Mail established (1885); Hull’s first Synagogue (1886), the building of East Park (1887); County Borough status (1888); the Boulevard Stadium (1895); Hull Cricket Circle (1898); Hull City status (1897); The opening of King Edward Street and Jameson Street (15 Oct 1901); Hull Telephone exchange (1902); the opening of an electric tramway on Hedon Road (17 Dec 1903); Hull City Football Club founded (1904); Beverley Road baths, opened 29 May 1905); the Wilberforce Museum (1906); Riverside Quay (1907); the building of Hull City Hall (1909); the first Theatre De Luxe (1911); King George Dock (1914), Hull’s first cinema, The (Tower) Pavilion Picture Palace (1915) and the Councils Guildhall and law courts, also completed in 1915.

Better Housing: New streets were laid out in the 1860’s and new terraced housing built from the 1870’s onwards. In 1891, the number of houses in Hull was 49,387, which increased to 53,398 houses in 1895, and 60,237 homes in 1906. This eased overcrowding, as Hull’s population grew from 186,292 in 1885, to 291,118 by 1914. Between 1899 to1906, the Council demolished 604 unfit houses and structurally altered another 71 to make them habitable. In 1903, 200 houses were cleansed and ‘lime washed’ and a halt was made on cellar dwellings. The first Council Houses’ were built at Upper Union Street in 1904. In 1908, Reckitt’s opened Hull’s first Garden Village, which by 1913, included 600 houses, built in five sizes, in twelve different styles, and with streets named after trees and shrubs. Facilities included a shopping centre, club house, a hostel for female workers, as well as several almshouses.

Public Parks: The first public park in Hull was Beverley Park, which opened in 1860. West Park opened in 1885. The Council provided work for the unemployed in the form of the construction of East Park. However, workers were so weak, that they collapsed and had to be replaced by labourers’ from the East Riding. Local benefactors also funded four parks, including Pickering and Pearson Park.

Learning and Education: The Ragged and Industrial School opened in Mill Street in 1849 with voluntary workers to feed clothe and train neglected and vagrant children. The boys learned cobbling, joinery and tailoring, the girls, sewing knotting and housework. A School of Art was opened in Hull in 1861. A Technical School followed it in 1894 and Hull Central Library also opened in 1894. Many charity schools were opened to provide children with some basic education. In Hull, the Cogan School in Salthouse Lane, was foundered for “clothing and instructing 20 poor girls”, who received three years of schooling in domestic science. Inspired by religion, these schools taught children to be “dutiful and obedient”. Thomas Ferens provided an art gallery and sponsored local libraries. By 1897 there were 33 Council schools within the City. In 1914, it was only compulsory to attend school until the age of 12. Many children left school early to work and support their families. Only 6% of children remained at school over the age of 16.

Improved Public Health: The Council founded the ‘Victoria Hospital for Sick Children’ on Park Street in 1873, a pre-school ‘Child Health Service’, and also a ‘Health Clinic’, in Jameson Street. A Maternity Hospital was built on Hedon Road in 1887, and the Castle Hill hospital was established in 1911. Mrs Edwin Robson opened a Maternity hospital, at 569 Holderness Road in 1912. A four storey, 240 bed, Naval Hospital was also completed on Argyll Street in 1914. (It still stands today behind Hull Royal Infirmary.) Mother and Infant Welfare Clinics were opened between 1915-9, based at 14 Kingston Square, 70 Dansom Lane, Clarendon House, on Spring Bank and 69 Coltman Street. Hull’s improving health also owes much to the pioneering work of Doctor, Mary Murdoch, and her assistant Doctor, Louisa Martindale, who shared a practice at Grosvenor House, located at 120 Beverley Road. Both women shared a crusade to improve women’s lives in Hull and also started a women’s suffrage society, holding committee meetings in their house, which attracted 200 attendees. In 1904, Mary Murdoch, became founding president of Hull’s NUWSS (National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society), attracting hundreds of members and forming branches in nearby towns. Mary often acted as NUWSS branch delegate during out of town trips, such as when they visited London to present a petition to the House of Commons. Louisa eventually returned to her home in Brighton, but Mary continued to be an inspiration to local women, even driving voters to the polls in her open top carriage during the local by-election of 1907, decorated with the red, white and green colours of the suffrage movement. In 1910, Mary Murdoch became Hull’s first female GP Doctor, a remarkable achievement at the time. She served as the Senior Physician at the Victoria Hospital for Sick Children, where she worked from 1892, until her death. She also became involved in several public campaigns including working to improve the appalling living conditions in the city. When war broke out in 1914, Doctor Murdoch dedicated herself to helping the sick and injured, but sadly died in 1916 after a fall in the snow, visiting one of her many patients.

New Council Services: Street widening, better drainage, public baths and laundries reduced the spread of infectious diseases. The water supply from the River Hull was abandoned and clean water supplies from Cottingham and Spring Head were established into the City. An electricity generating station was built in 1893 to provide some street lighting. A volunteer Fire Brigade was also formed from 1887. The Council began Public refuse collection in 1901. It established street cleaning, street lighting; water filtration, and food and public Health inspections to improve general living conditions. The Council opened cemeteries, and built the Hull Crematorium on 2nd January 1901. This was the first municipal crematorium in Britain. The Council also operated two Workhouses and a number of orphanages to provide some relief to the poor and disadvantaged.

Sport, Clubs and Entertainment: Societies and clubs began to emerge to provide recreation and education. The Young Peoples’ Institute (YPI) was established in 1860, at 36 George Street, to promote the “intellectual, moral and religious improvement of young people.” 700 members enrolled in its first year and it expanded in 1891 by purchasing 1 & 3 Charlotte Street. The Hull Boy’s Club was established in Roper Street, on the 18th November 1902, to promote sport and “train youth to be good and useful citizens”. It was a centre for boxing. By 1891, Hull had 15 bicycle dealers to support a growing number of weekend cyclists. There were street bands, and the Police band performed concerts in the parks. One park concert by the Artillery band attracted ten thousand people. The Hedon racecourse was opened in Preston. New swimming baths were opened in 1885, 1898 and 1905. By 1914 there were 29 Cinemas and Halls showing films in the city. Hull also had many pubs and beer was cheap, about two pence a pint, which proved a huge attraction for working men. Hull has always been a great sporting city. Both of Hull’s professional rugby league clubs and football team were well established before the First World War. Hull Football Club, formed in 1865, by ex public school boys from York, became one of the founding members of the Northern Rugby Football Union formed in 1895.  .Hull Kingston Rovers rugby team began in 1882, as Kingston Amateurs. They were made up of young boiler makers form the West Hull shipping industry and originally played rugby at Gillett Street, off Hessle Road. The Hull City Association Football Club was formed in June 1904 and played their first football matches at the ‘Boulevard’ the home of Hull FC. Hull Cricket Club was founded in 1875 and the Zingari Cricket club in 1896. Both cricket clubs remain today, literally across the road from each other, on Chanterlands Avenue, Hull. There were also many running Clubs operating in Hull at the time. These included the East Hull Harriers, Speedwell Harriers, Central Harriers, Hull Harriers, St Marks Harriers, and Stepney Harriers. Some of the Clubs even staged runs on Thursday afternoons to cater for shop workers who were off work on half day closing. The Hull Kingston Swimming Club was formed on 5th August 1886 as an amateur club for men. Its motto was ‘Kingston First’. It grew at an astonishing rate with more than 200 members being enrolled in its first year. (It was at this Hull club, that one of it’s famous Olympians, Jack Hale, invented the ‘Dolphin Method’ or butterfly stroke.) Such is Hull’s passion for sports, Hull formed its own ‘Pals battalion, the 12th East Yorkshires, known as the “Hull Sportsmen’s” battalion. During the course of the war, the 12th EYR, lost 366 men, with 138 of them killed on one day, at the Battle of Ancre, on the 13th November 1916. Jack Cunningham won Hull’s first Victoria Cross, with the 12th Sportsman Battalion on this day.

.Hull Kingston Rovers rugby team began in 1882, as Kingston Amateurs. They were made up of young boiler makers form the West Hull shipping industry and originally played rugby at Gillett Street, off Hessle Road. The Hull City Association Football Club was formed in June 1904 and played their first football matches at the ‘Boulevard’ the home of Hull FC. Hull Cricket Club was founded in 1875 and the Zingari Cricket club in 1896. Both cricket clubs remain today, literally across the road from each other, on Chanterlands Avenue, Hull. There were also many running Clubs operating in Hull at the time. These included the East Hull Harriers, Speedwell Harriers, Central Harriers, Hull Harriers, St Marks Harriers, and Stepney Harriers. Some of the Clubs even staged runs on Thursday afternoons to cater for shop workers who were off work on half day closing. The Hull Kingston Swimming Club was formed on 5th August 1886 as an amateur club for men. Its motto was ‘Kingston First’. It grew at an astonishing rate with more than 200 members being enrolled in its first year. (It was at this Hull club, that one of it’s famous Olympians, Jack Hale, invented the ‘Dolphin Method’ or butterfly stroke.) Such is Hull’s passion for sports, Hull formed its own ‘Pals battalion, the 12th East Yorkshires, known as the “Hull Sportsmen’s” battalion. During the course of the war, the 12th EYR, lost 366 men, with 138 of them killed on one day, at the Battle of Ancre, on the 13th November 1916. Jack Cunningham won Hull’s first Victoria Cross, with the 12th Sportsman Battalion on this day.

(see http://ww1hull.org.uk/index.php/our-loses/the-sportsmen)

Employment Opportunities: There was growth in seed crushing mills along the River Hull. Local companies like Reckitts started to take a paternal interest in its workers, providing pensions, and profit sharing schemes. Reckitts built the ‘Garden Village’ housing scheme in East Hull in 1908. The building of the Hull and Barnsley railway line in 1885, opened up the massed markets of the Yorkshire hinterland, Lancashire, the Midlands and beyond. By 1914, Hull was Britain’s third largest port in terms of trade and Britain’s biggest fishing port. Hull was also a major passenger port, with over 2 million people passing through the city to America and beyond.

Transport: The Council established an electric tram system in 1899, following the five main roads in Hull. Two of these lines went west, and two east. The fifth went to the north, and branched to include extra lines serving suburban areas. Three tram depots were established at Hessle Road (near Regent Street), Temple Street and Jesmond Gardens. By 1914, there were 180 trams, operating along 20 miles of track throughout Hull. Trams allowed people to move quickly, safely and cheaply away from their work place, and this spread new housing and wealth along the main roads into the city. Large houses were built along Hessle Road, Beverley Road, Spring Bank, Holderness Road and Cottingham Road.

Communications: Hull’s telephone system, which opened in 1880, and purchased by the Council in 1906, became unique in the United Kingdom for having a Council owned telephone system, with its own cream coloured telephone boxes.

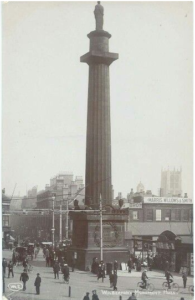

Civic Pride: A new City Centre, was planned and built, at the turn of the Century to improve the City’s status. Hull attracted more wealth and visitors. Hull gained a new municipal boundary in 1885, and three Parliamentary constituencies, known as Hull East, West and Central. Hull became a County Borough in 1888 and was awarded City status in 1897 and the first Hull citizen became Lord Mayor in 1914. In 1903, the Royal Family visited Hull to open Victoria Square. In 1904 a memorial to the dead of the South African war was erected outside Paragon train station. Hull City Hall was built in 1909 and the Guildhall, on Alfred Gelder Street, as built between 1904 -1916. However, despite rapid progress and many improvements, Hull remained extensively poor with only a few pockets of affluence. This was typical of many British cities. In 1914, about 80% of the British people were defined as ‘working class’ and did not own any property. One percent of Britain’s richest people owned 70% of the wealth. The average weekly wage was only £1.40. Life expectancy for a wealthy man was 55 years. Most people in poorer parts of Cities were lucky to live beyond 30 years old. Women worked, mostly as maids, cooks and servants, and did not have the vote. There were no female Members of Parliament and only half of men could vote. The fishing industry in Hull, which employed large numbers, was a tough life for those who sailed. It was also grindingly hard for the men and women who made nets, gutted fish, washed the quays and worked on the docks. Hull was tied to the sea and when the catch was poor, or trade fell, livelihoods were badly affected. The First World War was particularly hard on Hull. When the war started, Hull’s direct trade with Germany fell by 12% and removed job prospects in Hull almost immediately. For many, joining the armed services offered a uniform, regular meals and wages. The ‘King’s Shilling’ given to all those who enlisted, was not just an attractive option, but an only option.