Britain’s War Memorial. We tend to approach war memorials with pathos and a narrative about the futility of war, but the generation that built them were actually proud of them. People wanted to show the pride of sacrifice. They even experienced joy that their fathers, husbands and sons, had stepped up to the plate in the time of need. War memorials were defined in positive terms – as ‘Defence against aggression’, for ‘Justice’, ‘Liberty’ and Glory’. They were a sign of a colossal generational effort to “end all wars, for humanity” and celebrate the gift, that those who fell, gave to future generations.

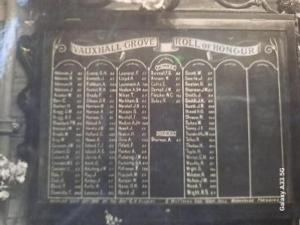

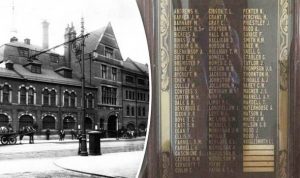

There were therefore many ideas put forward to commemorate the Great war and the people who fought in it. This resulted in a wide variety of memorials. There were official tokens of remembrance in the form of memorial plaques, issued to relatives of the fallen and commemorative “Peace” medals. Charitable care for ex-Servicemen was begun under the auspices of the Flanders Poppy Fund. The red poppy is now internationally recognized as a symbol of Remembrance, with its roots in the tragedy of the First World War. Memorial rolls of honour were put up in factories, sports clubs, railway stations, schools, and universities. Church windows were designed and dedicated to military units or individuals. Memorial buildings were constructed to provide “living memorials”, for example, as community centres, places for rehabilitation, or worship.

After the First World War, communities were keen to erect memorials to remember their dead. Unlike Belgium, France and Italy, the majority of Britain’s 750,000 war dead, are buried overseas and have no known graves. In fact, Britain in 1915 pursued an active policy, not to repatriate their dead and wealthy families who tried to, were often criticised. This spatial distance, absence from home, and deep sense of loss, has remained a strong part of family histories ever since. It is the reason why war memorials continue to be important in Britain, and commemorating the First World War still remains heartfelt, even after a 100 years. Over 5,000 memorials were raised in towns across Britain, in the first two years after the War, and some 37,000 exist today, in public spaces, in various forms. The demand for war memorials lasted many years and many were not completed until long after the war. The variety and diversity of permanent war memorials may well have been inspired by Hull’s earlier Street Shrines.

Hull Street Memorials.

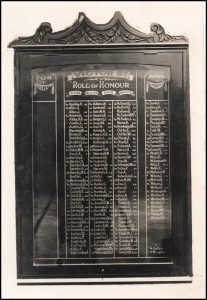

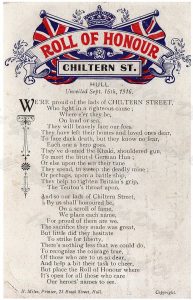

The first and earliest war memorials in Hull, were the Street ‘Rolls of Honour’, started in 1915. They commemorated all those locally serving in the armed forces. The idea of street war memorials started in South Hackney, in the East end of London, (Daily Mirror 11/05/1916), but it was soon adopted in other towns. These “wayside alters”, became particularly widespread in Hull, between August and December 1916, and by the end of 1916, Hull had at least 120 Street Memorials. They continued into 1917, when the Raglan Street and George Street Memorials were unveiled. They were supported by local churches and chapels, who observed a “spiritual awakening” in the community.

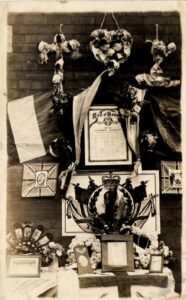

The names of servicemen, were often written on paper scrolls, or scratched onto wooded boards, and displayed prominently on Street corners. Some Shrines included only those men directly involved from the street, others included relatives from other streets. The memorials were often highly decorated, with flowers, flags and patriotic pictures, so much so, that they became known as ‘Street Shrines’. A great deal of work went into designing these ‘Rolls of Honour’. While designs and estimates were available from local Lithographers and Printers, (see advertisements in the Hull daily Mail, 25/10/1916), most Street Shrines and Rolls of Honour, were created by local skilled tradesmen and public spirited individuals. Women were prominent in organising and maintaining the memorials. The purpose being to be remember loved ones serving and particularly those who were lost at sea, or those killed, who could not be repatriated. By the beginning of 1917, Hull had already lost 3,500 men in the war, so there was massive demand to commemorate the war dead. The enthusiasm for street shrines was influenced by the propaganda film, “The Battle of The Somme”, which was released nationally, in August 1916. It was playing to packed audiences in the numerous Hull cinemas, at the time. The film gave the public a first time, glimpse of trench life and what men were doing at the front. The film was a morale booster, for an already patriotic public, and perhaps spurred communities to show their support for “their boys”, during the “Big Push”, which at the time, they thought would win the war.

Local committees were set up to create Hull’s street memorials. Memorials needed preparing, making, paying for, positioning and unveiling. Ladies went round each house, collecting names, information and money. The Memorials took many shapes, forms and styles. Some were made in stone, or wood. Others were lists of names written on parchments of paper. They often included poems, or a collection of framed photographs of men, or leading national figures of the time,like the King, Generals and Admirals. Many were innovative and creative. The Rustenburg Street Shrine, included, an embroidered East Yorkshire cap badge, a horse shoe made of bullet cartridges and at the top, a Harp with three broken strings, to represent, three lost lives, (HDM 25/09/1916).

The Street memorials were beautiful, colourful and numerous. The Hull Daily Mail, reported that : –

“A good deal of taste has been displayed in many decorations and everywhere people have “done things well.”

The May Terrace shrine on Walker Street, unveiled on 24 September 1916, was described as “of Gothic design, richly upholstered and enclosed in an outer case.” and….. “quite a showplace,…. for the residents put out in a line down the centre, tables containing photos adorned with glasses of flowers and coloured cloth, and there was a homely and pathetic touch furnished by memorial cards of relatives who have lost their lives. A cigar box stood on a table in this terrace, and the hundreds of visitors on Saturday evening [23 September 1916] and again yesterday [24 September 1916] were invited to contribute a copper for our sailors’ and soldiers’ tobacco.” The Church Lads Brigade and a local Boy Scout troop attended, “and the band played the general salute when the vicar drew the curtain.”

Similarly, “Walker Street to Tadman Street, possessed 30 to 40 shrines – canopied with flags, from end to end and scarcely a house, which was was not gaily dressed with bunting and displaying portraits of the King, Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener, with Admirals and Generals, of Britain and her Allies. Even the Terrace yards and squares, where the poor families dwell, were a brilliant mass of paper flowers and patriotic mottoes, while every window displayed the photo, either of soldiers, blue jackets, or minesweepers, who have left that house to fight for their country.” It continues, “The remembrance of these (Shrines), filled the hearts of many women who crowded before the shrine and moved them to tears.” (Hull Daily Mail, 25/09/1916)

The Exmouth Street, “Roll of Honour”, was Hull’s, first street shrine, in 1915. It was small and went unreported at the time, but was later acknowledged, (Hull Daily mail 11/07/1917).

Other streets, on Hull’s Hessle Road, also claimed the honour of being the first.

In November 1915, St Marks Church, was the first to erect a large, wooden board, on the railings outside, showing all the men

from St Marks Street serving in the war. This may have been Britain’s first War memorial. A similar Roll of Honour was unveiled at St Thomas’ Church, Campbell Street, Hull (HDM 15/11/1915). Other congregations followed suit For example, Queens Hall (645 men); Thornton Hall (435) and King’s Hall (422) listed a total of 1,502 men who had enlisted with 41 killed already by 1915. Individual Streets began their own Rolls of Honour around the same time.

Some small streets, like Alexandra Street, Warne Street and Sutton Street, clubbed together, to collectively produce their own “Street Shrine”. Six streets, at the south end of St George’s Road, unveiled their Rolls of Honour, on 30/08/1916. They included the names of 990 men serving. Other, ‘Roll of Honours’ covered many streets, such as Wilmington and Sculcoates Lane. St Andrews had a shrine, which only the people who worked on Hull docks saw. Some streets, like Wharncliffe Street, the home of Jack Harrison, VC, never had a “Shrine” (Hull Daily Mail, 10/12/1918 & 17/11/1919).

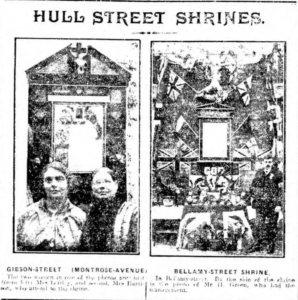

There was keen competition between Hull Streets, to provide the best memorials and collect the most money. Montrose Avenue, boasted the finest Street Memorial, Courtney Street the largest, and Northumberland Avenue drew the largest crowds. It was reported that the unveiling of the Wilmington Roll of Honour, on the 12th November 1916, attracted over 10,000 people, (HDM 13/11/1916). The opening ceremonies were often grand affairs, with bands, choirs, promiment singers, large crowds attending and were widely reported in the local newspapers.

The “Street Shrines” were usually unveiled by a local Councillor and blessed by a Clergymen. While each ceremony, was unique and personal, they followed a familiar theme and pattern. Guest singers would often sing a hymn, or patriotic songs, finished by the National Anthem, or “Last Post”. Neighbouring Terraces were festooned with bunting and union jacks. Windows often displayed photographs of serving men. Some opening ceremonies were solemn, with Hymns, sermons and prayers. Others, were less religious. Nearly all ended in a street party, even in the rain.

Some ceremonies caused incidents, such as the unveiling of the New George Street memorial, in Hull, on the 8th October 1916. Here, Thomas Boast, the local Greengrocer, had failed to display a flag in his shop, and was attacked by a crowd for being unpatriotic. Another example, was Emily Atkin, from New George Street and Alice Brown, from Scott Street, who were fined £5, for breaking a shop window and accusing the shop owner’s wife of being ‘Austrian’.

While Street memorials were widely popular, they relied largely on the goodwill of residents to maintain them. Local people were also expected to pay for them. Inevitably these ‘Rolls of Honour’, could not keep pace with mass conscription, the movement of men between regiments and the avalanche of casualties, over time. The names on the shrines were sometimes misspelt. Some also included relatives who lived elsewhere. There was also some opposition to the memorials, with people refusing to include names, or complaining that the money should be spent on the troops, or the returning wounded. Some criticised that names had also been mis-spelt, left out or ignored.

The memorials usually started small and there was insufficient space to record all the casualties. For example, Hull’s Bean Street, lost at least 102 men in the War; Waterloo Street 75; Barnsley Street 59; Walker Street 52, Spyvee Street, 51; and hundreds of men died from the packed communities of Hessle Road, Beverley Road and Holderness Road.

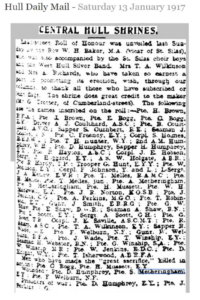

The Hull Daily Mail reported on many unveilings and printed a number of “Rolls of Honour”.

The Street Memorials were not necessarily accurate records. There were often mis spelt surnames, wrong initials, incorrect regiments, duplications, omissions, inconsistencies and other errors. Sometimes, the same servicemen appeared on several different memorials as soldiers moved address, or were included on memorials, by relatives in other streets, who themselves moved. Others included relatives who lived elsewhere, such as Sergeant, Sydney Johnson, 12th EYR, on the Bridlington Street shrine, but who was born in Boston, Lincolnshire and lived in Grimsby. Another was Percival Jones, also of the 12th EYR, who was born and lived in Goole.

A resident from Osbourne Street, complained to the newspaper that their Street Memorial should be reprinted, stating there were “dozens of mistakes” and some men had been omitted from the list, even though their names had been submitted (Hull Daily Mail, 1 Nov 1916). Similarly, the current marble memorial, at Eton Street, Hull, bears little resemblance to its original “Roll of Honour”, which included many more names of men killed in the war. These Street Shrine inaccuracies may have compromised their appeal and willingness to contribute towards them. For those compiling the local Rolls of Honour, it must have been a thankless task, keeping their memorials updated and accurate, to the satisfaction of everyone. Keeping pace with mounting casualties would have probably diminished the initial enthusiasm for the street shrine, which also became a mournful reminder of the sad side of war. The local press reported that “South Street, included the names of seven men who had fallen.” In Edgar Street, “four have been killed, one has been drowned and another one missing.” In Ropery Street, “five have been killed and one is a prisoner of war.” Grange Street, – “five killed, several wounded and two have lost limbs.” It may explain why Hull’s Street Shrines faded over time and were not repeated in the Second World War.

The administrative difficulties and declining enthusiasm for war, meant that many Street memorials were not updated after 1916. Most ‘Street Shrines’ were spontaneous gestures and only designed as temporary structures. They were not long lasting and deteriorated in poor weather. The “Street Shrines” became neglected, as the people, who maintained them passed away or moved on. Few rate payers wanted to pay for “Street Memorials”. Their maintenance relied entirely on voluntary contributions and local goodwill. The British Legion declined liability and the Hull Corporation did not adopt the Street Memorials. It was noted in 1922, that many of Hull’s Street Shrines were looking, “dirty, dilapidated and with the glass broken” (HDM 25/11/1922). A youth was witnessed, taking the flowers from the Walcott Memorial, handing then to a girl and kicking the vase down the street.

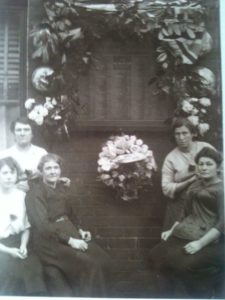

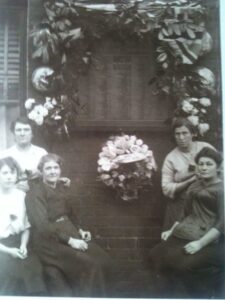

Margaret Calvert is the lady wearing the white blouse on the back left of the photo.

The young lady sat in front of her is Laura Calvert and the older lady in black, is Mrs Blanchard who lost two sons in the Great War.

There were however, some exceptions. The Courtney Street memorial, which had fallen into dis-repair, was re-erected in 1924. Similarly, Flinton Street updated their Hessle Road, Street Shrine, in November 1918. Church Street, Drypool, renovated their Street Memorial in 1923 (HDM 05/09/1923). Eton Street, converted their Roll of Honour, to a marble memorial in 1921, but ran out of money and included only a few of the men lost. The Walcott Street, Roll of Honour was still going strong in 1931, washed down fortnightly, flowers put in vases and re-varnished, from time to time, (HDM 11/11/1931). Similarly, the Residents of Gee Street and Wellsted Street, proudly maintained their memorial by attaching a weekend collection box, to pay for the cost of fresh flowers (10/11/1933). Bean Street residents raised funds to have their memorial renovated in 1931 (HDM 18/09/1931). Waller Street attempted to update their memorial long after the war, but this has now disappeared. Hull’s Street Shrines still remained an important focus for local Peace Parties and annual Remembrance services. However, when Hull’s Cenotaph was completed in 1924, they probably lost their significance.

Many of Hull’s Street Shrines were removed soon after the war. Some were placed in local school rooms, churches and chapels. The Mersey Street memorial for example, was relocated to Mersey Street school (HDM 03/02/1922). Bean Street moved their Street Shrine to Thornton Hall, in 1922, but because Bean Street covered three parishes, there was some debate whether this was the right place. (HDM 03/10/1921). Both buildings were lost in an air raid, during the Second World War. The Portland Street Shrine, was removed for safety in 1941, and placed in St Stephen’s church, which was then destroyed in the Blitz, in the same year.. The Alexandra Street, Warne Street and Sutton Street, was rededicated, on the walls of the Londesborough Street Recreation Club (HDM 22/12/1924). The Courtney Street, Roll of Honour was rediscovered years later in an attic, restored in 1924, but was again lost. Courtney Street lost 63 men in the war. The street was demolished and with it, faded the memory of this once proud, patriotic community.

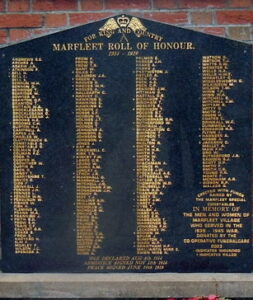

Many Street memorials, were destroyed during the Second World War blitz, which devastated 90% of Hull. Others were lost through slum clearance in the 1970’s and post war reconstruction. Just a few examples, of Hull Street memorials survive today. Most notably, these are at, Sharp Street, Newland Avenue, Eton Street, on Hessle Road and on Hull’s Dansom Lane. There is also the Marfleet memorial, but this is a modern update on the original. Other examples of street shrines are also preserved in the Hull Transport museum.

The street shrines have now become a reminder of the lost streets of Hull. The historic Drypool village of Hull, contained places like, Church Street, Raikes Street, Marvel Street, Wentworth Street, Bellamy Street, Prior Street and Feather Street. Each of these Streets proudly displayed their own Rolls of Honour. All were lost in the “blitz” during World War 2. Similarly, the “Shrines” in Hull’s Central West District, which contained the Rolls of Honour, for Bridlington Street, Holmes Street, Wainfleet Terrace and Finsbury Grove, were lost, during post war reconstruction. The part they played in the First World War is now largely forgotten.

The following ‘Street Shrine’ details were reported in the Hull Daily Mail during 1916. They give some idea of the popularity of Street Memorials, and the large numbers of men who enlisted. They also indicate the impact of casualties on these Hull communities.

Alicia Street and Christopher Street Shrine – 65 men serving (08/10/1916),

Aldborough Street Shrine – list 48 men serving including 5 dead (Hull Daily Mail 10/10/1916),

Alexandra Road – 77 Serving and 3 killed, (HDM 21/12/1916),

Alexandra Street, Warne Street and Sutton Street shared a memorial, which showed 261 serving and 9 dead (Hull Daily Mail 21/10/1916);

Balfour Street – 157 men serving, including 6 dead (HDM 09/11/1916),

Barmston Street – The shrine was attached to the rails of St Silas Church and unveiled on the 22/10/1916,

Barnsley Street – 256 men serving and 13 dead (Hull Daily Mail 14/11/1916),

Bean Street – 396 serving and 20 dead (HDM 07/10/1916),

Beaumont Street – 65 names,

Bellamy Street – 51 houses, 38 men serving, and 3 fallen (HDM 16/10/1916),

Blenheim Street – 83 serving and 5 dead (HDM 26/11/1916),

Brighton Street – 129 serving and 8 dead (HDM 30/08/1916),

Bridlington Street – 65 serving and 7 dead (HDM 24/12/1916),

Brunswick Avenue Roll of Honour – 12 men serving (HDM 21/11/1916),

Central Street & Main Street – 71 serving, 3 killed, 15 wounded of which 4 had been discharged from service, (HDM 17/11/1916),

Chiltern Street – 103 men serving;

Church Street – 22 men serving (HDM 10/11/1916),

Conway Street , Rosamond Street, and Sefton Street memorials, showed 167 men serving, 7 of which had been killed (Hull Daily Mail 12/09/1916),

Courtney Street, one of the largest Shrines, compiled by Mrs Russell, of 15 Grove Terrace. 305 names, 2 wounded, 1 missing, 16 dead. (HDM 10/10/1916)

Crystal Terrace, Courtney Street – 15 houses, 9 serving, 2 killed (10/10/1916)

Crowle Street Shrine, 262 men serving, arranged by Regiment, (03/11/1916)

Cumberland Street Roll of Honour – HDM 23/10/1916)

Dansom Lane Street Shrine – 142 men serving and 14 dead (HDM 23/10/1916),

Derby Street – 46 men serving (HDM 11/11/1916),

Epworth Street – 26 houses, 31 men serving, 1 killed, 2 wounded. Private, A Teasdale awarded the DCM. (HDM 29/11/1916),

Eastbourne Street – 122 serving plus the names of 13 killed (HDM 08/09/1916),

Emmeline Terrace, St Paul’s Street – 19 houses & 32 men serving;

English Street – 107 men serving and 12 dead (HDM 25/11/1916),

Eton Street – 260 Houses with 204 men serving, with three awarded gallantry medals, (HDM 22/09/1916),

Exmouth Street, Newland Avenue, Hull’s first Street Shrine, (HDM 11/07/1917),

Flinton Street & St Andrew’s Street Shrine – 300 names with 22 sailors and fishermen lost at sea (HDM 08/09/1916),

Gibson Street – 73 serving and 5 dead (HDM 25/11/1916),

Gillett Street, – affixed outside a barber shop, showed 325 men and 1 nurse. 24 were dead, (HDM 30/08/1916),

Glasgow Street – 91 served, 7 dead (HDM 01/10/1916),

Grange Street – reported 179 men, of which 5 had been killed and two had lost limbs, (HDM 26/09/1916),

Elm Street & Maple Street, Queens Road – 81 serving and 3 dead (HDM 25/10/1916),

Havelock Street – affixed to Dr Moir’s wall at the end of the Street. 127 names and one killed – (HDM 07/09/1916),

Haworth Street – 39 serving and 3 killed (HDM 21/12/1916)

Hull Old Town Shrine -188 men serving and 13 dead by 1916,

Lake Street – 55 men serving, including 5 killed (HDM 08/01/1917),

Liddell Street – 79 serving and 5 dead (HDM 23/09/1916),

Lincoln Street – 83 men serving (HDM 19/11/1916),

Liverpool Street – 182 men serving and 8 killed (HDM 30/08/1916),

Lockwood Street, “lists 103 names with 16 men dead, The Tock family at No:21 have 11 family members serving, including 7 sons. There are also 4 Gorrods, 3 Keeches, 3 Lamberts, and 4 Woods serving.” By 1916 it already shows 16 killed, 2 wounded and 2 Prisoners of War. (HDM 05/11/1916),

Lorne Street – 154 men serving, 9 killed, 19 wounded, 2 Prisoners of War and 2 others discharged (HDM 24/11/1917),

Manchester Street – 170 men serving and 5 killed (HDM 30/8/1916),

Marmaduke Street – 113 men serving, four killed, three wounded , 1 discharged (HDM 27/09/1916),

Massey Street – 70 serving and 4 dead (HDM 19/09/1916),

Mayfield Street – 39 serving and 2 dead (HDM 11/11/1916),

Mersey Street Shrine – 93 serving, 10 killed, 1 Military Medal, (HDM 30/12/1916),

Montrose Avenue, Gibson Street had 19 houses with 31 men serving, including five brothers. By 28/11/1916, three men had been killed, one was missing and 11 others had been wounded.

New George Street – 159 serving and 23 dead. 21 wounded, 5 Prisoners of war, and 15 Discharged. E Gould, EYR awarded the MC. (HDM 03/09/1916),

Newland Avenue, Salisbury Crescent and Woodbine Terrace Street Shrines affixed to No 127 Newland Avenue. Unveiled on 21/12/1916, it listed the names of 59 men serving, one of which had been killed (HDM 21/12/1916),

Nicholson Street, Tunis Street and Exchange Street Shrine – 174 serving and 4 dead, (HDM 16/10/1916),

Nornabell Street – 275 serving and 25 killed by 1916, 42 wounded, 1 missing & 1 prisoner of war. It unusually lists the dates on which each servicemen was killed, (HDM 08/11/1916),

Northumberland Avenue Shrine – 228 men served, of which 7 were killed, 2 drowned, 1 died, 1 died of wounds, 15 wounded, 6 Prisoners of War, and Private, J.L. Elston, EYR, was awarded the DCM.,

Norwood Street – 102 men serving and 12 killed (HDM 27/10/1916),

Old Town Memorial – 16 killed (HDM 01/12/1916),

Osborne Street – 163 serving from 115 houses. Six men from one house, 13 killed, 13 wounded & 1 prisoner of war (HDM 30/10/1916),

Park Road Shrine – 75 men served (HDM 11/11/1916),

Paisley Street Shrine – (HDM 23/10/1916),

Portland Street and Garden Street – 98 served and 7 dead (HDM 28/10/1916),

Porter Street and Michael Street – 116 men serving from 88 houses, of which 14 had been killed, 14 wounded, three of them wounded three times, and three others were Prisoners of War (HDM 04/10/1916),

Prior Street, Feather Lane, Prospect Place and Raike Street Shrine – 91 names serving in 1916,

Princes Road Street Shrine – 45 men serving (HDM 14/12/1916),

Providence Row – 181 men serving, and 12 reported killed (HDM 19/09/1916),

Raglan Street, Newland Avenue, – 80 names (HDM 11/07/1917),

Raywell and Russell Street Shrines described as a beautiful shrine within one of Hull’s poorest streets. It showed 77 men serving, 2 dead and 7 wounded (HDM 22/11/1916),

Redbourne Street and Newton Street -117 serving and 7 dead (HDM 13/11/1916),

Reform Street Shrine – 100 serving and 9 dead (HDM 25/10/1916),

Richmond Terrace and Cottingham Drainside Roll of Honour – 95 men serving and 5 dead (HDM 10/11/1916),

Rose Street – 50 houses, 66 men and one Nurse serving, 20/09/1916;

Rosemead Street Shrine – showed 127 serving and 7 dead (HDM 25/10/1916),

Rugby Street and St Andrews Street – 167 men serving and 10 dead (HDM 18/09/1916),

Rustenburg Street, New Bridge Road – 58 men serving, including 3 killed (HDM 25/09/1916),

Sarah Ann Terrace – 35 served , 3 dead (HDM 08/09/1916),

Scarborough Street – fastened to a house, showed 120 serving and 2 dead (HDM 30/08/1916),

Scott Street Shrine – 93 serving and 8 dead (HDM 09/10/1916),

Sculcoates Lane Shrine – 152 serving and 8 dead (HDM 09/11/1916),

Severn Street – 79 men serving, (demolished in a WW2 air raid)

Sharp Street, Newland Avenue – 139 served and 10 dead,

Shaw Street Shrine – 42 serving and 1 dead (HDM 18/11/1916),

Somerset Street Shrine, Hessle Road – 124 serving and 6 dead (HDM 28/09/1916),

South Boulevard Street – 112 serving, 9 dead (HDM 11/10/1916),

South Parade Street Shrine – 141 serving and 7 dead (HDM 03/10/1916),

Spencer Street – 131 serving and 8 dead (HDM 01/12/1916),

Spyvee Street Shrine – 238 men serving including 20 dead (HDM 28/10/1916),

Staniforth Place and Gilbert Street Shrine – 152 serving and 13 dead (HDM 04/10/1916),

Stanley Street – 196 men serving, and 4 dead (HDM 21/11/1916),

Strickland Street – 276 names – 24 killed and 3 Prisoners of War (HDM 26/10/1916),

Studley Street Shrine – (HDM 23/12/1916),

Subway Street – 146 serving and 8 dead (HDM 19/09/1916),

Sykes Street – 231 men serving and 17 killed, 27 wounded, 2 prisoners of war, (HDM 03/10/1916),

St Marks Street and Church Memorial – lists 152 names in 1915,

Trinity Street – 44 men serving (HDM 04/10/1916),

Walker Street – 300 men had enlisted and 22 dead (HDM 26/9/1916), https://ww1hull.com/hull-casualties/walker-street-1914-1918-memorial/

Walilker Street – 48 men serving and 2 dead (HDM21/11/1916),

Waller Street – 167 men serving and 15 killed (HDM 30/10/1916),

Waterloo Street, Sarah Ann Terrace, – 31 houses, 35 men serving, 3 killed and 2 wounded,

Welbeck Street Shrine – 72 men serving in 1916,

Wellsted Street and Gee Street showed 235 men serving including 12 dead (HDM 26/09/1916),

Wenlock Street – 26 men serving, (HDM 17/11/1916),

West Parade Street Shrine – 174 men serving and 19 dead (HDM 14/10/1916),

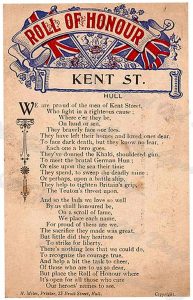

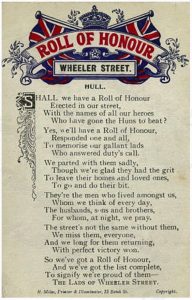

Wheeler Street, – 164 men serving (HDM 27/09/1916),

William Street – 144 serving and 11 dead (HDM 06/10/1916),

Williamson Street Shrine – 124 serving and 6 dead (HDM 08/11/1916),

Wilmington Roll of Honour – listed 460 names of those serving (HDM 13/11/16),

Witty Street – 70 men serving, of which 2 had been killed in 1916, (HDM 30/08/1916),

Worthing Street – 98 names & 5 killed (HDM 19/09/1916),

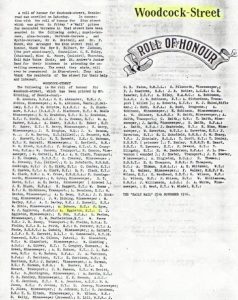

Woodcock Street – 215 serving and 5 dead (HDM 25/11/1916),

Wyndham Street and Wenlock Street, – 145 men serving (HDM 17/11/1916).

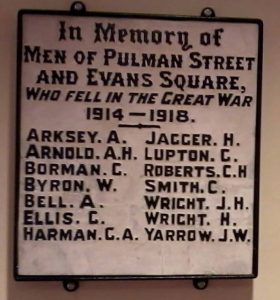

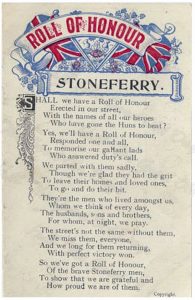

Below are some pictures of Hull’s Street Shrines at Providence Row, Newington Street, Courtney Street, and St Mary’s Terrace, Sculcoates Lane. Also Sharp Street, Aldbro Street, West Dock Avenue, Pulman Street and Evans Square, Stoneferry, Wilmington, Grange Street, Victor Street and the Groves area of Hull. They are part of Hull’s largely forgotten history of ww1.

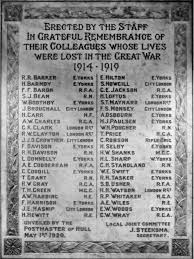

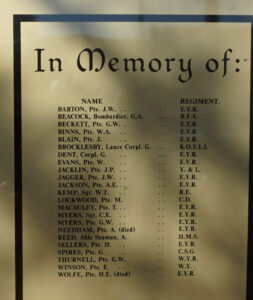

After the 1914-1918 war there was a great need to remember those who had served or died for their country. It was common for names to be listed on memorial boards, posters and plaques at various locations around Hull, paid for by companies where they had worked, churches, or by voluntary donations. Many Hull firms, such as Reckitt’s, Hammonds and the Wilson Shipping Line had their own workplace war memorials. The Hull & Barnsley Railway Company, displayed a bronze plaque, with the names of 183 men killed in the war. The Anlaby Road Wesleyan Church had a Great War Memorial, with 48 names, with the heading “Our Boys’ Response – all these offered themselves for service at the nation’s call. The prayers of this church are requested for our absent ones. God defend the right.”

Hull’s world famous Reckitt’s firm, saw 70 of its men join at the outbreak of war and by 1917, 820 men had enlisted. A total of 1,108 Reckitt employees, served from its world wide workforce, with 153 employees killed and 50% of the remainder wounded or disabled. In tribute to their service, Sir James Reckitt erected a memorial fountain in the grounds of its Hull Office, at Dansom Lane, which still stands today. See – https://ww1hull.com/the-financial-cost-of-ww1/hull-in-the-first-world-war/reckitts-ww1/

The Hull Post Office, which lost at least 46 men in the war, still retains a marble, memorial tablet, at their sorting Office, in St Peter’s Street. Schools also produced their own war memorials. Hull’s Hymers’ College built a memorial hall, in 1917, which contains the names of 116 former pupils, lost in the Great War. Similarly, Hull’s Grammar School Memorial, records the names of 88 former scholars. The Clifton Street School Memorial lists 66 pupils killed in the First World War. Hull’s Municipal Technical College, listed 52 former students on their Park Street ww1 memorial. The names of 28 Hull teachers are also recorded on a bronze tablet mounted in Hull’s Guildhall .

As a consolation, Hull City Council produced a book to commemorate the Peace after the First World War and these were given to all school children as a Souvenir.

After the War, remembrance became paramount, to ensure that the dead had not died in vain, and because so many men had no known grave. Like London, Hull built its own cenotaph to remember its war dead. It was erected, opposite the rail station, at Paragon Square, Ferensway, to a design by the Glasgow Architect, Mr T. Harold Hughes. Paid entirely through public donations, at a cost of £24,000, the Cenotaph was built by Quibell and Son (Hull), and unveiled on the 20th September 1924. The Hull Cenotaph is a simple, design, devoid of any representations of heroism and victory, or any religious symbolism. It provides a blank canvas, for the viewer to project their own feelings of war. Hull’s Cenotaph remains a successful design. Even today, it still evokes the eternal, human feelings, of death and loss and remains a gathering place for all remembrance events.

As a practical memorial to those who survived, Hull established the City of Hull Great War Trust, in 1918. It was funded through voluntary donations and proceeds were used to help those wounded and disabled and the dependents of those lost in the war. The Great War Trust was a unique idea pioneered in Hull and helped men and women from all forces, including the fishing fleet and mercantile marine. The Trust distributed nearly £300,000 and assisted over 4,000 people before it was closed in 1983.

On the 16th October 1927, the Kingston Upon Hull War Memorial was unveiled at the French village of Oppy. This remembered the men of Kingston-upon-Hull and all local units who gave their lives in the Great War: Many of the casualties of 31st Division who died at Oppy Wood, were from the Hull area. The ground of which the memorial stands was donated by the Vicomte and Vicomtesse du Bouexic de la Driennays, in memory of their 22 year old son Pierre, an NCO of the French 504th Tank Regiment, who was killed in action at Guyencourt on 8 August 1918. It too, is located on the village square of Oppy.

The following Pictures include: the Bronze plaque of the Hull Technical college, Park Street: Hull Boys Club Memorial formerly at Roper Street; the marble Post Office memorial, St Peter’s Square, Hull; Clifton Street School Roll of Honour 1914-18, Hull’s Cenotaph memorial, Paragon Square, and the Hull Kingston Memorial, Oppy Wood, France. For other memorials see the following link – http://www.hull-peoples-memorial.co.uk/Database/Memorials/Memorials.php

Thank You to “Hull, the Good Old Days” Facebook, for many of the photos included on this page

Cross of Sacrifice, Hull Northern Cemetery (431 WW1 Graves). Identical Memorial Cross’ are located at Hull Western Cemetery (494 WW1 graves) and Hedon Road Cemetery, East Hull (249 CWGC graves).

Thank you for the link, telling the life story of Ernest Loveday and his family. Much appreciated. Paul