A separate, but related event to the Great War, was the great 1918 flu pandemic. It exclusively attacked human beings and not other animals. This deadly flu virus infected more than one-third of the world’s population, and within months had killed more than 50 million people – three times as many in World War I – and did it more quickly, than any other illness in recorded history. Unlike other flu outbreaks which happen every year and vary in severity, this particularly flu virus attacked young, healthy adults, aged between 20-40. There was no cure, no vaccine and little support that medicine could provide.

A separate, but related event to the Great War, was the great 1918 flu pandemic. It exclusively attacked human beings and not other animals. This deadly flu virus infected more than one-third of the world’s population, and within months had killed more than 50 million people – three times as many in World War I – and did it more quickly, than any other illness in recorded history. Unlike other flu outbreaks which happen every year and vary in severity, this particularly flu virus attacked young, healthy adults, aged between 20-40. There was no cure, no vaccine and little support that medicine could provide.

It affected 200,000 British troops, 400,000 French and 500,000 German troops. Some argue that the virus accelerated the end of WW1 and tipped the balance of power, in the later days of the war, towards the Allied cause. Data reveals that the viral waves hit Germany before the Allied powers and that both poor health and mortality in Germany and Austria were considerably higher than in Britain and France.

The origins of this virulent new strain of the flu are still unknown. It is believed that the flu virus came from wild birds and spread to farm animals, like ducks, chicken and possibly pigs. The first known flu victim was Albert Gitchell, a farmer from Haskell County, Kansas, who worked with animals and was later conscripted into the army. As a camp cook at Fort Riley, Kansas, USA, Gitchell quickly spread the virus while serving food to troops and was the first recorded to die of this flu. Within three weeks, 1,100 soldiers in the camp were infected and 38 had died. Lack of knowledge about the new virus, meant it was not properly diagnosed or properly contained, The flu was therefore accidentally carried to Europe by infected American forces personnel. One in every four Americans had contracted the influenza virus and 25 American Troop Transports, left for Europe in March 1918. They arrived at the Port of Brest in France and the troops were quickly moved to the front. By April 1918, the flu had broken out in the trenches. The virus travelled through infected people, along roads and railways, criss-crossing Europe, and soldiers carrying the hidden virus back home. In Britain, Glasgow was the first city to be infected. By June 1918, the first flu cases appear in Manchester, and then London. The disease spread rapidly through the continental US, Canada and Europe. It eventually reached around the globe, partially because many were weakened and exhausted by the famines of the World War.

The killer Flu spread in waves between 1918-1919.

4th March 1918 – Pandemic – Day Zero – Albert Gitchell maybe the first flu victim, Fort. Riley’s Camp, Funston, Kansas, USA.

April 1918 – Pandemic + 40 Days – 20 million infected. 20,000 dead.

June 2018 – Pandemic + 100 Days – 130 million infected in USA and Europe. 200,000 dead.

September 1918 – Pandemic + 180 days – 150 million infected in USA and Europe. 250,000 dead.

October 1918 – Pandemic + 210 days – The Flu spreads worldwide. 1.4 million dead.

November 1918 – Pandemic + 240 days – All Continents (except Australia) infected. Up to 60 million dead worldwide.

July 1919 – Pandemic + 500 days – Pandemic ends – up to 100 million dead worldwide, ten times more than all those killed in WW1.

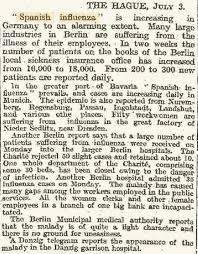

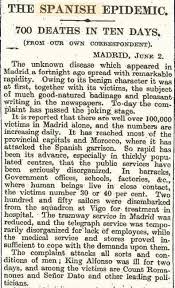

It was nicknamed ‘Spanish flu’ as the first cases were in reported in Spain’s uncensored press. Newspapers during World War One, were censored, (Germany, the United States, Britain and France all had media blackouts on news that might lower morale), so although there were influenza (flu) cases elsewhere in China and India, it was the Spanish cases that hit the headlines. In Spain, some 8 million people were infected in May 1918. One of the first casualties was the King of Spain, Alfonzo the 13th. In Spain they called it ‘French Flu’!

In three waves, the Spanish Influenza epidemic of 1918-1919, infected 500 million people across the world, including remote Pacific islands and the Arctic, and killed 50 to 100 million of them. This was three to five percent of the world’s population, making it one of the deadliest natural disasters in human history. This particular virulent strain of flu was unusual, as it was most deadly for those between the ages of 20 to 35, making war veterans among the most susceptible. It seems that the strong immune systems of healthy people over reacted to the virus, destroying vital organs, starving the body of oxygen, turning lips and ears blue through the lack of blood supply, and attacking the lungs. Death was painful. Victims coughed blood and often drowned in their own mucus. The virus was distinct in that it had a rapid onset and it was not unusual for victims to die within hours. Another oddity was that the influenza appeared most deadly during the Summer months of the Northern Hemisphere, rather than the Winter.

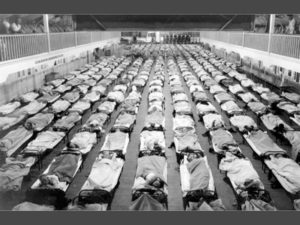

The Spanish Flu Becomes Incredibly Deadly. While the first wave of the Spanish flu had been extremely contagious, the second wave of the Spanish flu was both contagious and exceedingly deadly. In late August 1918, the second wave of the Spanish flu struck three port cities at nearly the same time. These cities (Boston, United States; Brest, France; and Freetown, Sierra Leone) all felt the lethal affects of this new mutation immediately. Hospitals quickly became overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of patients. When hospitals filled up, tent hospitals were erected on lawns. Nurses and doctors were already in short supply because so many of them had gone to Europe to help with the war effort. Desperately needing help, hospitals asked for volunteers. Knowing they were risking their own lives by helping these contagious victims, many people, especially women, signed up anyway to help as best they could.

The Symptoms of the Spanish Flu.

The victims of the 1918 Spanish flu suffered greatly. Within hours of feeling the first symptoms of extreme fatigue, fever, and headache, victims would start turning blue. Sometimes the blue colour became so pronounced that it was difficult to determine a patient’s original skin colour. The patients would cough with such force that some even tore their abdominal muscles. Foamy blood exited from their mouths and noses. A few bled from their ears. Some vomited; others became incontinent. They would drown in their own blood, struggle for breath and suffocate. The “Spanish Flu” struck so suddenly and severely that many of its victims died within hours of coming down with their first symptom. Some died a day or two after realising that they were sick. Not surprisingly, the severity of the “Spanish Flu” was alarming. People around the world worried about getting it. Some cities ordered everyone to wear masks. Spitting and coughing in public was prohibited. Schools and theatre`s were closed. People also tried their own homemade prevention remedies, such as eating raw onions, keeping a potato in their pocket, or wearing a bag of camphor around their neck. None of these things stemmed the onslaught of the Spanish flu’s deadly second wave. In 1918, the virus struck with fearsome speed, often killing its victims within hours of the first signs of infection. Eyewitness accounts of the time describe how a commuter began to cough and never made it home and how four women sat down to play bridge one evening and three were dead by the morning.

“Those afflicted were first aware of a shivery twinge at breakfast,” says Juliet Nicholson in “The Great Silence 1918-1920, Living In The Shadow of The Great War”. By lunchtime their skin had turned a vivid purple. By evening, before there was time to lay the table for supper, death would have occurred.”

Piles of Dead Bodies

The number of bodies from the victims of the Spanish flu, quickly outnumbered the available resources to deal with them. Morgues were forced to stack bodies like cord wood in the corridors. There were not enough coffins for all the bodies, nor were there enough people to dig individual graves. In many places, mass graves were dug to free the towns and cities of the masses of rotting corpses. In some town, the dead were left outside homes to be collected.

Armistice Brings Third Wave of the Spanish Flu

On November 11, 1918, an armistice brought an end to World War I. People around the world celebrated the end of this “total war” and felt jubilant that perhaps they were free from the deaths caused by both war and flu. However, as people hit the streets, gave kisses and hugs to returning soldiers, they also started a third wave of the Spanish flu. The third wave of the Spanish flu was not as deadly as the second wave, but still deadlier than the first. Although this third wave also went around the world, killing many of its victims, it received much less attention. People were ready to start their lives over again after the war; they were no longer interested in hearing about, or fearing a deadly flu.

Towards the end of 1918, a new nursery rhyme started to be heard in playgrounds across Britain, sung by skipping schoolchildren: “I had a bird, its name was Enza. I opened the door and in-flu-enza.” Like many such rhymes, its chirpy cadence, hid a far more macabre reality.

It soon became apparent that this was no ordinary flu and a few months later a more virulent strain had emerged. Doctors believed those who had contracted the earlier virus would be immune to this bout – but they were wrong.

In Britain, Glasgow was the first city to be affected in May and by June it had spread to London. By November, death figures reported in the newspapers were growing: “London County, 2,458; London outer ring, 1,705; Sheffield, 465; Leicester, 260; Hull, 220.”

In hindsight, Britain was woefully under-prepared for the outbreak. Britain’s Chief Medical Officer, Sir Arthur News-Holme, initially told Britons to simply carry on, advising just a few pointers: avoid sneezing and coughing in public, carry plenty of fresh handkerchiefs, wash hands regularly and gargle with disinfectant mouthwash. A mixture of mustard and Bovril was thought to boost the immune system, as was alcohol. Authorities were focused on the ongoing war effort, and Sir Arthur News-Holme, wanted normal life to go on, munition factories to remain open and public services to continue as they were.

However, Dr James Niven, the Chief Medical Officer for Manchester, seeing the full force of the flu in a crowded, industrialised City took an entirely different view. On his own initiative, he began conscientiously collecting and analysing figures to learn about the disease. When schoolchildren started to die, Dr Niven knew that the disease did not discriminate. He recommended the closure of all schools and cinemas. He wanted to reduce people’s proximity to each other – or as the concept is known today, enforce ‘social distancing’ measures. He also swiftly handed out 35,000 leaflets across Manchester, advising locals on how to reduce the risk of becoming infected with the virus and giving out strict instructions for the isolation of those that did. Dr Niven also organised the mass provision of free food, baby milk in particular, to combat starvation during the pandemic. Dr Niven’s provisions no doubt saved many lives. However, he was largely ignored by the Government. Following his retirement he suffered from depression and committed suicide on September 30, 1925. Another key worker, in the Pandemic, was Dr Basil Hood, the medical superintendent of St Marylebone Infirmary, Kensington. He provided front line, palliative care and gave a harrowing account of the Spanish Flu. “The staff fought like Trojans to feed the patients, scramble as best they could through the most elementary nursing and keep the delirious in bed!” “Each day the difficulties became more pronounced as the patients increased and the nurses decreased, going down like ninepins themselves,” Hood wrote. “Sad to relate some of these gallant girls lost their lives in this never-to-be-forgotten scourge and as I write I can see some of them now literally fighting to save their friends then going down and dying themselves.” By December, Hood was exhausted and collapsed sick. When he returned to the Infirmary in February, the epidemic was still raging and two more nurses had died, bringing the fatalities to nine. Revisiting his notes in retirement, Hood called the epidemic “the worst and most distressing occurrence of my professional life”. In all, the hospital had admitted 850 influenza patients, nearly half had developed pneumonia, and 197 had died. By the time the pandemic ended in April 1919, 250,000 Britons had perished. Other unsung heroes of the Spanish Flu, were the many women, who provided the majority of care during the pandemic, because the virus disproportionately affected young men. While their contribution is largely ignored, they helped shape the future for women in medicine, and provided female nurses of the time with a sense of professional fulfilment.

In Britain, coverage of the flu, was initially scant because of a reluctance to publicise a fatal disease to a public already saturated with news of mortality. It was only later – as the death toll mounted – that many schools, theatres and dance halls were closed and people were urged to stay at home. Streets were sprayed with chemicals and people wore anti-germ masks. Some councils insisted that cinemas be emptied every few hours to allow windows to be opened and halls aerated.

Hospitals were spilling over with the sick and dying, while some wards had to close because all the nurses were struck down. Some towns demanded signed health certificates before strangers could enter. There was a shortage of coffins, morticians and grave-diggers. Funerals had to be limited to 15 minutes. Other countries and states brought in their own legislation. In Arizona handshaking was outlawed. In France, spitting became a legal offence. US President Woodrow Wilson contracted the disease while negotiating the Treaty of Versailles and the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt died in its first wave.

Vaccines were available, but had no effect on those already infected, while millions died from secondary bacterial infections, which we would now treat with antibiotics. People did their best to prevent the influenza, people wore masks, public entertainment was curtailed. In October 1918, Australia, sealed the continent off from the outside world and established the first Quarantine Camp. In response to the pandemic, Britain created the first Ministry of Health in 1919, to ‘take all such steps as may be desirable to secure the preparation, effective carrying out and co-ordination of measures conducive to the health of the people’. This remains with us today in the form of the Department of Health and Social Care 2018.

Hull and the “Spanish Flu”

In Hull, the outbreak began during the last week of June 1918 and lasted for almost a year. During the period June 1918 to May 1919, a total of 1,261 deaths were recorded as being due to influenza, whilst deaths ascribed to pneumonia and broncho-pneumonia were considerably above the average for the previous ten years. The disease was not confined to the congested and crowded districts of the City, which indicated that insanitary conditions had no direct casual relationship with its incidence; it was prevalent in all parts and the person attacked were representative of every section of the community. The disease abated somewhat on two occasions during the twelve months that it was active. The first occasion being during August and September when four deaths only occurred over a period of eight weeks. The second occasion was much shorter in duration, deaths from influenza, declining in January until only one death was recorded during the last week of that month, but the figures rose again during February. The peak of the epidemic was in October and November 1918, when over a five week period, there were 684 Hull deaths, representing a little over half the total deaths during the whole epidemic period. Despite the high death rate, schools remained open and businesses carried on as usual. The disease was so widespread that it was considered no benefit would accrue from closing schools. However, letters were sent to the proprietors of cinemas and other places of entertainment advising them on the ventilation and disinfection of their premises. Handbills were distributed to the public detailing precautions which could be taken, and these were supplemented by the Health Visitors when they called on mothers in the poorer and more overcrowded parts of the City. Patients were removed to hospitals and houses were fumigated on request. Prophylactic vaccine was also made available to medical practitioners who wished to use it.

The ‘Spanish flu’ would kill over 228,000 people and 30,000 soldiers in Britain and between 50-100 million people worldwide. The following are some examples how the flu was reported locally.

Hull Daily Mail 1 July 1918

INFLUENZA OUTBREAK

PNEUMONIA FOLLOWS

At least a dozen persons in different parts of the Rossendale valley have

succumbed to pneumonia, following the disease [influenza]. On Saturday Pte

James Caine (30), Lancashire Fusiliers, died at 3, Turner’s Buildings, Stacklands,

Bacup, from pneumonia after only a few days’ illness. He had served with the

colours for nearly four years, and leaves a widow and five young children.

Private James H. Bell and Mrs Bell, of Edward Street, Haslingden, have lost three

out of four young children in ten days as a result of measles and the epidemic. All

the elementary schools at Bacup and Rawtenstall are to be kept closed for

another week, and all the factories, workshops, picture houses etc in Bacup,

Waterfoot and Rawtenstall are being disinfected as fast as possible.

(Identical report appeared in Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, on 1 July 1918)

Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, on 2 July 1918

THE INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC

Report includes the following…

‘…The wife and the father of Air Mechanic Pepperday, R.A.., Plantation Street,

Bacup, have died from the effects of the disease whilst the soldier was at home

on leave….”

Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 3 July 1918

INFLUENZA RAVAGES

‘…Yesterday the death occurred at 9, Wellington street, Britannia, Bacup, of

Frances Barlow (15), a mule spinner at a local mill, and daughter of Lance-Corporal

James Barlow, R.E., who is in France. She had been ill only a few days from

pneumonia succeeding influenza. Her two sisters are ill with the same malady.

Patrick Walsh (58), one of the founders of the Bacup Irish Club, died yesterday

from the disease…’

Birmingham Post, 6 July 1918

INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC

MANY DEATHS THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY

(reports of deaths throughout the UK includes the following)

Two more deaths following influenza were reported at Bacup, one being a

woman who had been married only a few months. It has been decided that the

Rawtenstall elementary school shall remain closed until August 6.

On 29th May 1918, the Hull Daily Mail reported that a type of influenza was sweeping through Spain.

The ‘Spanish plague’ was causing many deaths and the Government offices in the country had closed.

Many businesses were also forced to shut their doors and two thirds of the tramway staff were off work ill.

The Hull Daily Mail reported on the 28th June 1918 the strange flu had hit officially hit Hull. The lengthy article reported a policeman had collapsed in the middle of Woodcock Street as a result of the “Spanish Flu.”

The first recorded victim was an Indian seaman who had sailed into Hull and died on board his vessel once it was docked. Official death records show that he was a 25 year old with the surname of Nomezulla.

Dr Riley, director of education in Hull, reported no unusual absences in Hull schools due to the virus, but one Hull doctor revealed over 100 cases a day were passing through his surgery, with at least 20 serious cases visited at home. He added that “a few fine days and it should be all cleared away.”

The reality of the situation struck home when children started dying. On the 1st July 1918, it was reported Kate Denman, an 11 year old of Hodgson Street, had passed away of the condition. An inquest heard her lungs were in a state of inflammation and that the cause of death was pneumonia caused by influenza.

The second case reported was of Elsie Barton who was the 9 year old daughter of a soldier who died under similar circumstances at her home in Arthur’s Terrace, off Courtney Street.

Hull Death tolls

At the end of 1918 the total death toll, according to the Annual Health Report from the Hull Medical Officer, was 975. The worst affected area was South Newington, with 122 deaths reported, and the worst age group affected was those between 25 years old and 45 years old, with 280 people dying in the city in that age bracket.

First Wave of the virus

Much like the current pandemic, the Spanish flu came to Hull in devastating waves. Initially it was thought the outbreak lasted a year but the official medical report stated Hull suffered three outbreaks between 1918-1919, with the first wave hitting Hull in June and July 1918, the second wave hitting in October, November and December 1918, and the third wave arriving in February, March and April 1919. It stated that it did not matter what social class or what district you lived in, everyone was at risk.

The first wave claimed the lives of 78 people, the second wave 872 deaths, with the third wave claiming 265 lives.

The authorities decided it was pointless closing schools, they felt the disease was so widespread among the population it was a pointless exercise.

Self-isolation

One of the leading lights at the time of the outbreak in Hull was Dr Wright Mason, the Medical Officer of Health for Hull. He told the Hull Daily Mail the best option for anyone with symptoms would be bed rest and to keep warm.

He warned meeting with other people was dangerous and aided the spread of the disease, and that this led to unnecessary risks, and secondary complications.

He also said confined spaces such as railway carriages, closed vehicles, and public resorts were prime locations for the spread and warned the young and people with colds and sore throats were more susceptible.

He insisted efforts had been undertaken in Hull to stop the spread and Hull Corporation Sanitary Authority were hard at work, but the disinfection of houses was not required.

He advised all people needed to do at home was to keep rooms ventilated and keep fresh air flowing through the room, with the patients who were suffering to be kept wrapped up warm and out of draughts.

One of the strangest twists came on July 12, 1918, when a letter writer to The Hull Daily Mail advised the best way to combat influenza was to eat raw onions. The writer revealed he had been an eater of raw onions for years and had never had influenza.

Hull Second wave

On October 10, 1918 another wave of influenza had arrived, and was hitting hard in many provincial centres. A large outbreak was reported in north-west Hull. Dr Wright Mason was asked whether he was going to close the schools to stop the spread, but said he had not made a decision.

It was also reported that a clerk in the employ of the Hull Corporation had suffered two deaths in his family, when his children, aged six and two, had died as a result of the influenza.

Medical advice

Dr Wright Mason issued a statement entitled “Precautions against Influenza,” and featured a step by step guide on how best to avoid the disease.

It stated early symptoms included an increase in temperature, irritation of the throat, severe pain in the eyes, head and back, and tenderness of the muscles, especially in the legs and back.

It warned anyone with these symptoms should be put into isolation, in a bed, in a warm room, and medical assistance sought immediately. It was said that if this was done the risk of spreading the disease would decrease. Any children showing early symptoms should be kept from school and the head teachers immediately notified.

On the termination of the illness, all the bed and clothing from the room should be thoroughly cleaned, and the room cleansed, with the windows thrown open to allow fresh air and light to enter.

But schools remained reopen and parents were asked to act quickly if children were showing symptoms.

Mask wearing

Like today, the wearing of masks were a hot topic. On the 9th November 1918, it was reported that Hull residents might have to wear masks in a bid to stop the spread.

The American Army had invented a mask that was proving to be successful and delivering a high degree of immunity. The mask would be worn over the mouth and nose and was made from impregnated gauze.

Very few people wore the mask at the time and at least one person was pulled before the police courts for refusal to wear a mask in a public place.

An order was made by the Government that from November 25, 1918: “No entertainment shall be carried on for more than three hours consecutively. “There shall be an interval of not less than thirty minutes between any two entertainments. “During the interval the place shall be effectually and thoroughly ventilated. The rules applied to cinemas, theatres, music halls, pubs, clubs and other venues.”

Third wave

On February 15, 1919, the disease was once again spreading in the north of England and was present in Hull.

Dr GW Lilley told warned there were signs of an increase in cases. He said there was no need to worry and that cases were predominantly among the aged. The Hull Medical Officer for Health in Hull reported there had been 12 deaths in Hull in the previous week, compared to the 9 cases the week before.

Counting the cost

Every Friday reports were published showing the weekly death figures but, while the third wave was prominent in Hull, figures begin to drop and death tolls decreased.

By the end of the outbreak, the total number of deaths in Hull from Influenza was 1,261. “Spanish Flu” ended up killing around 50 million people worldwide, which left a death toll three times higher than those killed during the First World War.

One of the high-profile casualties of the Spanish Flu outbreak was Sir Mark Sykes, the MP for Hull Central. Part of the Sledmere-based landowning Sykes family dynasty, he had served as an Army general during the First World War and played an important role in the subsequent peace negotiations in Paris where he represented the British government. However, while he was in the French capital in early 1919 he contracted the disease and died in his hotel. He was just 39-years-old.

The Influenza Death Toll 1918-1919

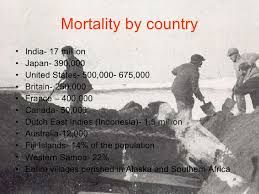

The exact global mortality rate from the 1918/1919 pandemic is unknown, but an estimated 10% to 20% of those who were infected died. About a third of the world population infected, with between 3% to 6% of the entire global population killed. Influenza may have killed as many as 25 million people in its first 25 weeks. Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people, while current estimates say 50–100 million people worldwide were killed. The disease killed in every corner of the globe. The country that suffered most was India. The first cases appeared in Bombay in June 1918. The following month deaths were being reported in Karachi and Madras. With large numbers of India’s doctors serving with the British Army, the country was unable to cope with the epidemic. As many as 17 million died in India, about 5% of the population.

In Japan, 23 million people were affected, and 390,000 died.

In the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), 1.5 million were assumed to have died from 30 million inhabitants.

In Tahiti, 14% of the population died during only two months. Similarly, in Samoa in November 1918, 20% of the population of 38,000 died within two months.

In the United States, about 28% of the population suffered, and 500,000 to 675,000 died. Native American tribes were particularly hard hit. Entire villages perished in Alaska. In Canada 50,000 died.

In Brazil 300,000 died, including president Rodrigues Alves.

In Britain, as many as 250,000 and 30,000 soldiers died; in France and Germany more than 400,000.

In West Africa, the influenza epidemic killed at least 100,000 people in Ghana. In British Somaliland one official estimated that 7% of the native population died.

Gone but Not Forgotten

The third wave of this Influenza lingered. Some say it ended in the spring of 1919, while others believe it continued to claim victims through 1920. Eventually, however, this deadly strain of the flu disappeared, or evolved into a less harmful type of flu in order to sustain itself. More people died of influenza in that single year than in the four years of the ‘Black Death’ Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351. By the end of pandemic, only one region in the entire world had not reported an outbreak: an isolated island called Marajo, located in Brazil’s Amazon River Delta. Strangely, despite the deadly losses, there are almost no public memorials to the victims of Spanish Flu.

To this day, no one knows why the flu virus suddenly mutated into such a deadly form or why it ended so suddenly. Nor do they know how to prevent it from happening again. Scientists and researchers continue to research and learn about the 1918 “Spanish Flu” in the hope of being able to prevent another worldwide pandemic of the flu. The ever mutating nature of the bird flu virus, means that the threat of killer flu enveloping the world again still persists one hundred years on. In March 2018, the Global Health Council announced a Flu Pandemic was the Number one, health risk to the planet, and could kill 300 million people within two years. In recent years, there have been further outbreaks of new flu virus’s. These include Ebola, in West Africa and SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) in Asia. In 2020, another deadly pandemic, known as “Coronavirus”, or “Covid 19”, emerged form China. Entire nations were forced into “lock down”, with billions of people put into self isolation, for months, to stem the contagion.