Due to its coastal location many men joined the Navy in its many forms. As a City with long standing maritime history, Hull men served throughout the world in the Royal Navy, Royal Marines, Naval Reserve, Merchant Service and the Hull Fishing Feet. 14,000 merchant seamen were to die in the war, over a thousand of these were from Hull. 4,000 of these sailors died in just three months during 1917, when the German U Boat attacks peaked. Hull played a crucial contribution to Britain’s war at sea. As well as supplying the Royal and Merchant navy with experienced crew and vessels, Hull fishermen cleared mines and ensured safe shipping lanes along the East coast. They hunted enemy submarines, carried cargoes, protected convoys and defended Britain’s fishing fleet. Some facts were:-

During the First World War, 300 Hull ships were used as minesweepers and for searching submarines. 61 Hull minesweepers, were lost during the war.

The first Hull vessel sunk by a mine was the ‘IMPERIALIST H250’, on the 6th September 1914, 40 miles ‘ENE’ of Tynemouth.

Hull’s first Auxillary patrol vessel lost, was the HMT ‘COLUMBIA’. She was attacked by E Boats off Forness, on the 1st May 1915, with only one survivor.

Hull also lost 68 fishing vessels during the WW1.

The first Hull vessel sunk by a German U-Boat was the ‘MERCURY H518’, on the 2nd May 1915.

On 3rd May 1915, eight Hull Vessels were sunk by submarine while fishing in the same area of the North Sea. These were the, ‘BOB WHITE H290’, ‘COQUET H831’, ‘HECTOR H896’, ‘HERO H886’, ‘IOLANTHE H328’, ‘MERRIE ISLINGTON H183’, ‘NORTHWARD HO H455′, and ‘PROGRESS H475’.

Only 93 Hull trawlers were used for fishing during the war, and all fish & chips shops were closed in Hull throughout the war.

Nine fishing trawlers from Hull were lost by mines, although others which were listed as missing may have met the same fate.

The Humber ports of Hull, Goole, Immingham and Grimsby, supplied over 880 vessels & 9,000 men from the fishing trade to the war effort.

In total, 670 fishing vessels, were lost from the Humberside region, of which 214 were minesweepers. Hull lost 129, of these ships, including 61 minesweepers.

By the end of the War, only 91 of the 300 Hull owned ships were afloat, 9 of which had been built during the war.

The Thomas Wilson & Sons Shipping line, which had started with 92 vessels, lost 56 Steamers during the war (3 captured, 49 sunk and 4 damaged, plus 401 crew). The losses were so considerable, that the company was sold to Sir John Reeves Ellerman, another shipping rival, on 13th November 1916.

Hull lost over 1,200 merchant crewmen, another 267 Royal Navy sailors and 38 Royal Marines. The majority of these died at sea and have no known grave.

At the end of the First World War, Lord Jellico declared that the Royal Navy had saved the Empire, but it was the fishermen in their boats who had saved the Royal Navy. The Royal Naval Reserve of fishermen was “a Navy within the Navy“. They swept mines, escorted convoys, hunted U-boats and carried out countless dangerous duties. While often overlooked by Admiralty officials, there contribution was at least recognized by Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon who said; ‘It is doubtful if we could have defeated the Germans, at any rate as quickly as we did defeat them, if it had not been for the assistance which the Royal Navy received from the fishing community.’ Thomas Crisp and Joseph Watts, were two former fisherman, serving in the Royal Naval Reserve, who were awarded the Victoria Cross during the war.

Hull ships and crews played a major part in that victory. The ongoing peril of unexploded sea mines continued to take the lives of Hull fisherman, long after the war had ended. For example, the Hull Trawler, Sapphire, was blown up by a mine, off Spurn Point, on 20th February 1919. Gitano’ struck a mine and was sunk with all hands on the 23rd December 1918. The Hull Trawler ’Scotland’ struck a mine, off Flamborough Head, on the 13th March 1919, killing 7 Hull men. Two days later, the steam ship, ‘Durban’ exploded‘, killing another eight Hull sailors. The ‘Isle of Man’ (Hull) exploded on the 14th December 1919, killing a further seven Hull fishermen. The steam ship ‘Barbados’ exploded on the 5th November 1920, taking ten Hull men. These included the two Weaver brothers killed on the same day. Many of these seaman had survived the war, only to be its victims after.

Dangerous work for fishing trawlers used as minesweepers

When the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) was first created in 1859, it consisted of up to 30,000 merchant seamen and fisherman who the Navy could call on in times of crisis. Fishing trawlers were strong, sturdy ships, designed to withstand severe weather conditions out at sea, and in 1907 the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet, Admiral Lord Beresford, recognised that trawlers could be used as minesweepers. His recommendation led to the formation of the Royal Naval Reserve (Trawler Section) in 1910, with approval to mobilise 100 trawlers during any crisis period and enrol 1,000 men to man them. It also introduced a new rank, that of ‘Skipper’ RNR, into the Navy List. By the end of 1911, 53 skippers had joined. In 1912 a further 25 enrolled and the Trawler Section of the Royal Naval Reserve, consisted of 142 trawlers manned by 1,279 personnel. 31 more skippers joined before the war started in August 1914, making a total of 109 skippers. Another 315 more volunteered by the end of the first week in October. By the end of 1915 the Mine sweeping Service employed 7,888 officers and men. By the end of the war, 1,467 steam trawlers had been taken into Admiralty service, with 1,502 drifters being used for Auxiliary Patrols and 39,000 fishermen drafted into the Royal Naval Reserve Trawler section.

The Royal Naval Reserve (Trawler Section):

Before the war started there were already 142 trawlers in the Trawler Section of the RNR and 109 skippers enrolled. During the first week of the war in 1914, 94 trawlers were allocated for mine sweeping duties and dispersed to priority areas, including Cromarty, the Firth of Forth, the Tyne, the Humber, Harwich, Sheerness, Dover, Portsmouth, Portland and Plymouth. They were supplied with mine gear, rifles, uniforms and pay as the first minesweepers. They were commanded by naval officers, some from the retired list, who had received a brief training in mine sweeping. Apart from the skippers, officers were also required to supplement the handful of naval officers of the existing mine sweeping service. Most of the trained pre-war RNR and RNVR officers had already been called up for service in the Fleet. For the new mine sweeping and auxiliary patrol flotillas, officers and civilians were obtained from the Merchant Navy and given temporary commissions in the RNR and RNVR. To bolster naval discipline, various Royal Fleet Reserve and pensioner petty officers were distributed among the vessels.

Sea mines were explosive devices left in the water to explode on contact with a ship or submarine. Over the course of the war some, 247,000 sea mines were laid in the world’s waters, with more than 190,000 of these laid in the North Sea. The Germans laid 25,000 mines in 1,360 minefields around the British coast and over 17,800 mines, in 60 separate minefields off other waters worldwide. Mines were difficult to see, relatively cheap to make and very effective once they had struck a target. They were also prone to breaking away from their moorings, drift with the changing winds and currents, making them an indiscriminate hazard to all shipping. The British Admiralty created a new Mine Clearance Service in 1919 to make the worlds sea lanes safe again. The service employed 700 officers and 14,500 men organised into 55 different flotillas. They divided the seas into regions, each overseen by a Mine Clearance Officer and swept the seas of mines around the British Isles, the Dutch coast, the Baltic, Mediterranean and the Black Sea. These “Minesweepers” would sweep’ mines using cutting wires, bring them to the surface, then detonate them with rifle fire. Moored mines only had a short length of chain shackled to them. The rest of the mooring was wire cable or even sisal rope in some cases; otherwise the mine could not support the weight of its mooring, particularly in deep water. This was the part of the mooring, that the sweep wire or any fitted cutter, was intended to sever. Sometimes gathering a group of mines together could lead to multiple explosions. A chain reaction could result in one massive detonation which would often sink the minesweeper. Mines also snagged in fishing nets and exploded on deck when hauled aboard. Collison between vessels during minesweeping manoeuvres were a constant hazard. Mine sweeping was therefore extremely dangerous work. As a Journalist commented at the time, It required ‘nerve, skill and unremitting watchfulness’. Fifty crew and four ships were lost clearing mines in the Dardanelles alone. Three more vessels were lost clearing mines in home waters during 1919 and another two in the Mediterranean. It was not until November 1919 that much of the sea mines had been cleared, but not in time for three Hull fishing Trawlers to be sunk in 1919 by stray mines.

How did they ‘sweep’ mines?

Early mine sweeps simply comprised of chains towed over the seabed between two ships, or even by a single ship to drag mines and their moorings out of a channel. These were later replaced with serrated wire cables towed between two ships (Actaeon Sweep). Development of the Oropesa Sweep, with its diverters and depth-keeping kite, allowed sweeps to be towed by a single ship. Sweep wires were made from flexible, steel wire rope and streamed from each quarter of a minesweeper. The cables were laid right or left-handed according to the side streamed. This helped the wires achieve hydrodynamic lift and spread. A single strand in each wire was laid in the opposite direction to provide a serrated cutting effect.

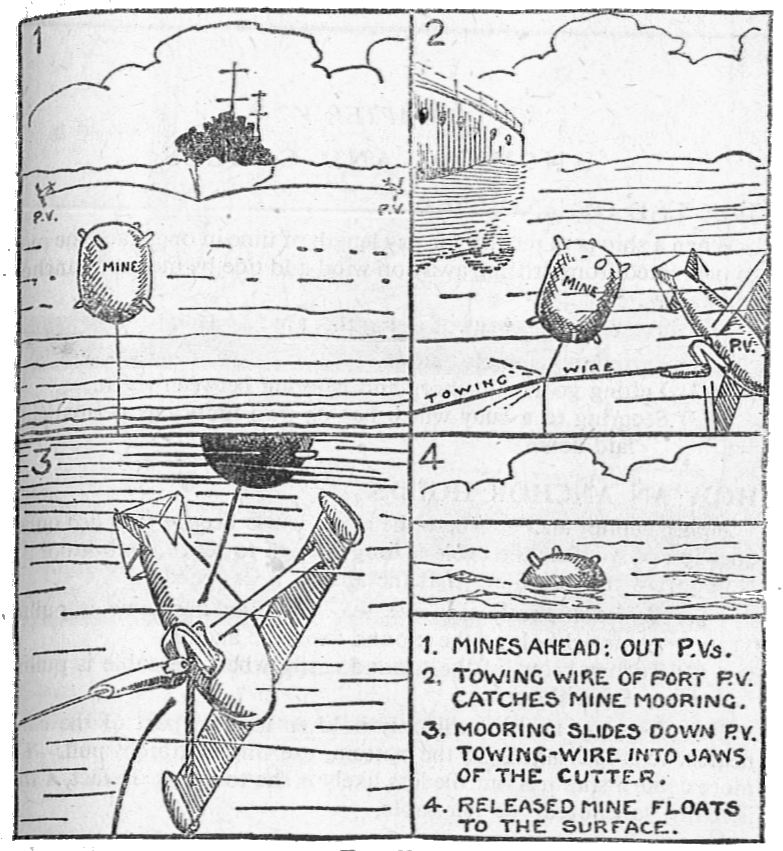

The ‘Paravane’, a form of towed underwater “glider”, was developed from 1914–16 by Commander Usborne and Lieutenant, C. Dennistoun Burney, funded by Sir George White, founder of the Bristol Aeroplane Company. Initially developed to destroy naval mines, the paravane would be strung out and streamed alongside the towing ship, normally from the bow. The wings of the paravane would tend to force the body away from the towing ship, placing a lateral tension on the towing wire. If the tow cable snagged the cable anchoring a mine then the anchoring cable would be cut, allowing the mine to float to the surface where it could be destroyed by gunfire. If the anchor cable would not part, the mine and the paravane would be brought together and the mine would explode harmlessly against the paravane. The cable could then be retrieved and a replacement paravane fitted. Burney explosive paravanes were deployed from torpedo boat destroyers in a configuration known as the ‘High Speed Sweep’ to counter submarines. However, most paravanes were non-explosive and were streamed by larger warships and merchant ships as self-defence measures to divert moored mines away from their hulls. They comprised a wire streamed to each side from the bows with a float secured to the end to divert it outwards.

The wings of the paravane would tend to force the body away from the towing ship, placing a lateral tension on the towing wire. If the tow cable snagged the cable anchoring a mine then the anchoring cable would be cut, allowing the mine to float to the surface where it could be destroyed by gunfire. If the anchor cable would not part, the mine and the paravane would be brought together and the mine would explode harmlessly against the paravane. The cable could then be retrieved and a replacement paravane fitted. Burney explosive paravanes were deployed from torpedo boat destroyers in a configuration known as the ‘High Speed Sweep’ to counter submarines. However, most paravanes were non-explosive and were streamed by larger warships and merchant ships as self-defence measures to divert moored mines away from their hulls. They comprised a wire streamed to each side from the bows with a float secured to the end to divert it outwards.

ur_collections/source_guides/ships_and_shipping.aspxhttp://www.hullcc.gov.uk/museumcollections/collections/theme.php?irn=158

http://www.mylearning.org/local-heroes-hulls-trawlermen/p-2631/

http://www.hullhistorycentre.org.uk/discover/hull_history_centre/

http://www.naval-history.net/WW1LossesBrFV1914-16.htm

http://www.scarboroughsmaritimeheritage.org.uk/auboatsarthurgodfrey.php