The Outbreak of War in Hull

On Tuesday, 4th August 1914, at 11 pm, Great Britain declared war on Germany. It was a gloriously, sunny, Bank Holiday and holiday makers were disappointed that the trains on the North East railway lines had been cancelled for troop transport. The news was greeted by an outbreak of excitement and patriotism. Crowds gathered outside the Hull Daily Mail offices, in Whitefriargate, to hear the news. When Germany refused the ultimatum to withdraw from Belgium, a cheer and patriotic singing broke out. The next day saw hysteria in the shops with panic food buying and hoarding. There was a sudden scarcity of sugar and fruit as the Wilson Line ships were detained in the ports of Hamburg. Prices rose and supplies fell, until order was restored. Hull was full of troops called up and on the move. The Territorial Army was mobilised to defend Britain, while the Regulars were sent to France. The 4th and 5th (Cyclist) Battalions of the East Yorkshire Regiment marched to the coast and dug in, ready for invasion. The Royal Field Artillery from Wenlock Barracks were recalled to Hull from Dundee. Some 300-400 reservists of the regular army left Paragon station for Chatham and other depots. The Posterngate shipping office was busy with Royal Navy Reserve, ‘hard looking, wiry men’, responding to the call, to sign on. Guards were placed on factories and power supplies to prevent sabotage, hospitals were prepared to accept casualties, and appeals for volunteers went out. The docks were full of vessels, as Hull’s 400 fishing trawlers headed for the safety of home. Hull’s Fish Dock was full of a flotilla of ships from the Red Cross and Hellyer’s fleets. Amidst of all this activity, the Government passed the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) on 8th August 1914. This gave it far reaching powers over people. Land and property could be seized for military use, suspected spies could be arrested and imprisoned. Strict censorship of the Press was enforced. In effect, the country was placed under martial law. Tradesman surrendered their horses at the Carr Lane livery stables and motor vehicles were commandeered by army officers in Hull. Sir Mark Sykes, Hull’s Central MP, mobilised 1000 Yorkshire farm wagoners from his estates, which caused a blow to farmers and the local harvest. Father Le Clerc, Chaplain of Endsleigh convent, left Hull to join the 13th French Regiment. Lady Nunburnholme, appealed for volunteers to join First Aid classes and nursing courses, at her VAD, Head Quarters, in Peel Street, Springbank, Hull.

The Belgium Refugees

The German invasion of neutral Belgium and the stories of their atrocities towards the Belgians was a powerful weapon in uniting Britain’s support for the war and in recruitment. On 9th September 1914 Hull established it’s War Refugee Committee to assist refugees until the end of the war. It’s HQ was based at Bowalley Lane and it had 500 volunteer helpers, 400 of which were women. This was a registered war charity that relied entirely on voluntary aid. The committee’s work was twofold. First, to offer hospitality to Belgium residents in their area and secondly to give relief to those disembarking at their ports. This included giving temporary relief with accommodation, food and clothes and for more permanent cases rent free lodgings and allowances for food, clothes and heating. For those who could work, jobs were sought for them. On the whole the refugees were found to be sober, industrious and gracious and many became self supporting during their stay in Britain. The Hull War Refugee Committee for Belgium , in its final report, stated that 1,249 refugees were assisted of which 612 were entertained and 637 were given some temporary material aid. In total, the Committee had received £10, 386 in voluntary subscriptions, donations and collections. This was used to assist and maintain refugees and aid their repatriations.

Support Services

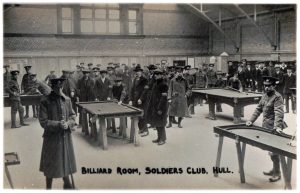

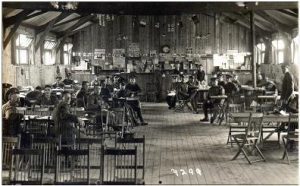

‘Soldiers Clubs’ were raised in Hull to help serving men. A Soldiers Club with reading room was located at Beverley Road baths on Stepney Lane and run by Major A J Atkinson and his wife.

A ‘Soldiers & Sailors Wives Club’ was formed on Mason Street by Mrs Hubert Johnson, the wife of the Lord Mayor. It was devoted to provide relaxation for the wife’s of servicemen away from home.

Paragon Railway Station housed a popular ‘Rest Station and canteen’ well used by departing troops. It was set up in September 1914 and staffed throughout the war by Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD).

‘Peel House’ at 150 Spring Bank, was the VAD headquarters, and run by the Lady Mayor. Peel House helped train nurses and locate hospital accommodation for soldiers posted to Hull. It also sent out thousands of parcels of clothing and essentials to troops home and abroad. War Correspondents in France were struck by the way East Yorkshire Units were looked after by people back home. Its most renowned work was sending thousands of food and clothing parcels, plus other necessities to Prisoners of War. This work was extended to captured seaman and interned civilians. Peel House raised public funds to fund their work. The residents of Freehold Street created a bread fund and distributed food to Prisoner of War through Peel House.

Recruitment

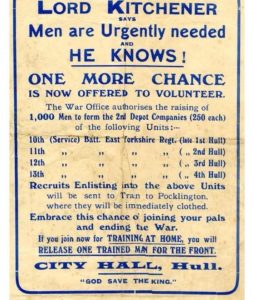

Large numbers of men rushed to enlist in the Army. Recruitment drives were launched, these appealed to men’s patriotism and sense of duty. Local authorities and prominent people took the initiative in recruiting and equipping ‘Pal’ Battalions, confident in the fact that the war office would take them over. This allowed work-mates and friends to serve together and was hugely popular. 30,000 men had joined by the end of August 1914, and 2 million men volunteered by the time conscription came in 1916. In eleven weeks Hull raised enough men to form four infantry battalions (4,000 men in all). The battalions were given unofficial names, reflecting the men’s backgrounds. For example, the 1st Hull Pal Battalion, were known as the ‘Commercials’ because its recruits were from Hull’s commercial and office sector. Other Hull Battalions were made up of local ‘Tradesmen’, ‘Sportsmen’, and Railway workers. The motives for joining were varied – a desire to travel, to escape low paid work, for adventure, but above all a genuine idealism and patriotism. This was the base on which the New Armies and Pal’s battalions were formed. Local papers reported on families at war, that had joined the cause. The ‘Hull and Lincolnshire Times‘, of 29th May 1915, reported on James Fray, of 72 Flinton Street, Hull, with seven family members enlisted, Sergeant, Herbert Thundercliff, wounded at 48 Beeton Street, with ten family members serving and Mr T.G. Marshall, of 96 St Georges Road, with five sons serving and another 15 family members enlisted, including nephews and son in laws.

Large numbers of men rushed to enlist in the Army. Recruitment drives were launched, these appealed to men’s patriotism and sense of duty. Local authorities and prominent people took the initiative in recruiting and equipping ‘Pal’ Battalions, confident in the fact that the war office would take them over. This allowed work-mates and friends to serve together and was hugely popular. 30,000 men had joined by the end of August 1914, and 2 million men volunteered by the time conscription came in 1916. In eleven weeks Hull raised enough men to form four infantry battalions (4,000 men in all). The battalions were given unofficial names, reflecting the men’s backgrounds. For example, the 1st Hull Pal Battalion, were known as the ‘Commercials’ because its recruits were from Hull’s commercial and office sector. Other Hull Battalions were made up of local ‘Tradesmen’, ‘Sportsmen’, and Railway workers. The motives for joining were varied – a desire to travel, to escape low paid work, for adventure, but above all a genuine idealism and patriotism. This was the base on which the New Armies and Pal’s battalions were formed. Local papers reported on families at war, that had joined the cause. The ‘Hull and Lincolnshire Times‘, of 29th May 1915, reported on James Fray, of 72 Flinton Street, Hull, with seven family members enlisted, Sergeant, Herbert Thundercliff, wounded at 48 Beeton Street, with ten family members serving and Mr T.G. Marshall, of 96 St Georges Road, with five sons serving and another 15 family members enlisted, including nephews and son in laws.

However, in 1915, the flow of volunteers was insufficient to meet the army’s needs and public opinion began to turn towards the ‘slackers’ – those men who had not enlisted. In October, Lord Derby, the Director of Recruitment asked all men, aged 18 to 41 to “attest” – to say they that they would join up when called. Men were divided into married and single groups and young, single men would be called up first, before married men. Arm bands were issued to attested men, to spare them the humiliation of being labelled as ‘slackers’. This voluntary recruitment initiative failed to produce the numbers of recruits needed and was replaced with compulsory conscription. On the 5th January 1916, the Military Service Act deemed all single men between 18 and 41 to have enlisted, a second Act in May, extended this to all men between 18 and 41. Finally, with the crises of 1918, a third Act in April, extended the age limit up to 51. However, few of the older conscripts saw action at the Front – rather they formed a home defence force.

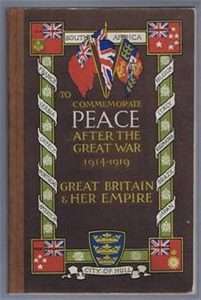

Hull’s contribution during the First World War is often underestimated. As a North Eastern, coastal City with a population of approximately 300,000, over 70,000 men served extensively across all branches of the British Army, Royal Navy, Merchant Navy, Royal Air Force, and the Home Defence. They also died serving Commonwealth nations, such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand where they had emigrated. The outbreak of war in 1914 aroused great enthusiasm in Hull and within the first six months 20,000 local men had enrolled. Hull was also attacked by Zeppelins and it raised its own Pals Battalions. The Great War affected everyone. At home there were wounded soldiers in military hospitals, refugees from Belgium and later on German prisoners of war. There were food and fuel shortages and disruption to schooling. The role of women changed dramatically and they undertook a variety of work undreamed of in peacetime.

Hull formed its own four ‘Pal’ Battalions, the 10th, 11th, 12th & 13th service Battalions of the East Yorkshire Regiment, which made up the 92nd Infantry Brigade, 31st Division. Due to its coastal locality and economic and social make up, Hull formed its own ‘bantam’ regiment made up of men of small stature, with “big hearts”. Hull formed its own heavy artillery and Garrison Brigade to defend the Humber estuary. The 17th Northumberland Fusiliers, a Railway Pal’s Battalion was also formed at King George’s Dock in Hull.

Due to its maritime history, Hull men also served throughout the world, in the Royal Navy, Royal Marines, Royal Naval Reserve, Merchant Service and the Hull Fishing Feet. Hull’s population fell by about 45,000 during the First World War. 75,000 men served in the war effort. Over 7,500 Hull men were killed and over 14,000 were wounded during the First World War. Many of these lived men in the same streets or terraces, which was to make the casualties keenly felt by the local community. The numbers of wounded increased over time, causing considerable hardship for Hull families. The Hull Lord Mayor, Alderman, Hargreaves, reported on 21st February 1919, that 14,000 Hull men had been wounded in the war of which 7,000 had been maimed. Some 12,000 Hull women had also been dealt with by the local Pensions Committee. On 9th September 1924, the Ministry of Pensions recorded that this had increased to 20,000 disabled ex servicemen from Hull and they were dealing with 2,500 Hull widows, 200 motherless and fatherless children and 3,000 Hull mothers and other near dependants. Hull City Council established a Great War, Civic Trust, to assist with the large numbers of widows, wounded and orphans left after the War. This ran until 1963 and raised £165,000.

Thank You to “Hull, the Good Old Days” Facebook, for the above photos.