OPPY WOOD, 3rd May 1917 – The Hull Pals Attack

The Capture of Oppy Wood was an engagement, North East of Arras, between May and June 1917. The Germans were in possession of a fortified wood to the west of the village of Oppy, which overlooked British positions. The wood was 1-acre (0.40 ha) in area and contained many German observation posts, machine-guns and trench-mortars. The aim of the attack was to remove this defensive obstacle and divert German resources away from the main offensive, planned at Messines in early June 1917. In military terms, Oppy Wood was a diversionary attack, by the 92nd Brigade, of the 31st Division,during the Third Battle of the Scarpe (3–4 May). It was an attack on a half mile front, in unfavourable conditions, and against impenetrable German defences. It is also known as the Battle of Gavrelle. However, for the people of Hull, Oppy Wood, would be forever remembered as the place where the Hull Pals made their name. In fierce fighting around the village, Hull lost more men on the 3rd May 1917, than any other. The attack failed and the final casualties totalled 326.

The Capture of Oppy Wood was an engagement, North East of Arras, between May and June 1917. The Germans were in possession of a fortified wood to the west of the village of Oppy, which overlooked British positions. The wood was 1-acre (0.40 ha) in area and contained many German observation posts, machine-guns and trench-mortars. The aim of the attack was to remove this defensive obstacle and divert German resources away from the main offensive, planned at Messines in early June 1917. In military terms, Oppy Wood was a diversionary attack, by the 92nd Brigade, of the 31st Division,during the Third Battle of the Scarpe (3–4 May). It was an attack on a half mile front, in unfavourable conditions, and against impenetrable German defences. It is also known as the Battle of Gavrelle. However, for the people of Hull, Oppy Wood, would be forever remembered as the place where the Hull Pals made their name. In fierce fighting around the village, Hull lost more men on the 3rd May 1917, than any other. The attack failed and the final casualties totalled 326.

The main British attacking forces in this battle were the 10th, 11th and 12th Battalions of the East Yorkshire Regiment, known as the ‘Hull Pals’. They advanced up a slope, in the dark, in four waves, over difficult terrain, illuminated by German rockets and Very Lights. They faced Oppy Wood, which was elaborately fortified, and defended by experienced German troops. They struggled forward over three belts of barb wire entanglements. Unable to keep pace with their barrage, and were exposed to murderous German machine gun fire. Despite this, the Hull Pals continued to advance. One company fought their way into Oppy village itself, while the rest were held up. After attacking three times, they were forced to withdraw under constant fire. During the action, 2nd-Lieut. John Harrison, of the 11th Battalion, silenced an enemy machine-gun post single handedly and was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Preparations for the attack on Oppy began on the 1st May 1917. Officers and NCO’s of the 10th and 13th EYR, went forward to check the assembly positions and returned next morning to issue equipment for the advance. At 11pm on the 2nd May, the 11th and 12th EYR Battalions started to move to their assembly positions. The 10th EYR moved at 11.30pm. Start time for the attack was to be 3.45am on the 3rd May, with the 10th EYR positioned on the right flank, the 11th EYR in the centre and the 12th EYR on the left flank, all opposite Oppy Wood. A preliminary bombardment by nine Field Artillery Brigades and the use of extra machine guns was expected to cut the barb wire, neutralise all German resistance and leave the trenches intact for the Pals to occupy. In reality, this failed to happen for a number of reasons.

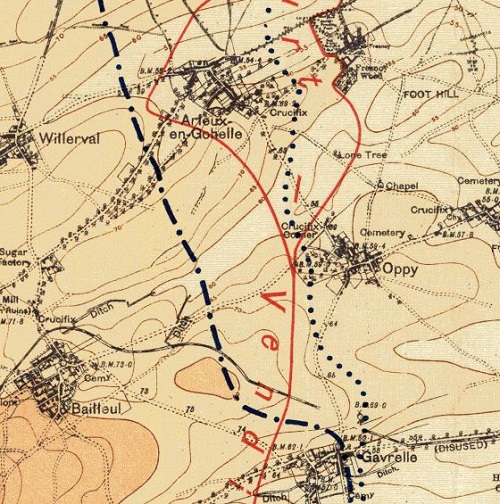

(Oppy Wood on a Trench Map & Oppy Village under fire.)

1. On the 28th and 29th April, the Battle of Arleux had been fought on the same battleground and the 13th EYR had suffered a number of casualties. The assembly positions which had been heavily shelled, offered little cover and debris from that battle littered the ground, hindering coordinated movement. The 10th EYR Battalion history records that the assembly trenches were “barely four feet deep, with no communications to the rear, nor any means of contact to left or right.”

2. Oppy Wood was full of fallen trees and tangled branches which gave the enemy great cover. A long slope of 1,000m to the west, left the British field artillery at extreme range. This reduced its accuracy and largely failed to cut the enemy wire.

3. Oppy wood was a strongly defended position, guarded by experienced German soldiers. In front of Oppy Wood, lay a well organised trench system, protected by barb wire and good communications, which covered the Oppy wood and village from flanking attacks. The wood itself contained a large number of machine gun posts and all along the German lines, machine gun posts and mortars were well placed to repel any attack. The area was held by the 1st and 2nd German Guards, which the East Yorkshire Regimental history describes as, ‘some of the bravest of the enemy troops’. The Germans had strengthened the wood by developing defensive tactics learnt from the earlier Somme battles. The British had expected to encounter demoralised troops and thought that the creeping barrage would neutralise all resistance. However, some of the German wire at the south-western corner of the wood was uncut and rather than being shaken, the Germans were actually massing for a counter attack.

4. It was originally intended to make a night assault, to evade German machine-gun fire. However, the Third and First armies needed to attack in daylight and Douglas Haig enforced a compromise zero hour of 3:45 a.m. No preparations had been made for an advance at night, such as, putting out boards, luminous paint on the German wire, taking compass-bearings or organising intermediate objectives. Sunrise was not until 5:22 a.m. and it would not be possible to see objects in the dark, at 50 yards (46 m) until 4:05 a.m.

5. On the night of the attack, there was a full moon which did not set until sixteen minutes before the attack beagn. On many parts of the front, British troops assembling, were illuminated by the moon, exposing them to enemy fire. The 11th EYR war diary records “to get to the assembly positions, Companies had to go over the top of a rise within 1000 yards, with a moon low in the sky behind them.”

6. The German defenders saw the British infantry forming up in the moonlight, in an assembly trench just 250 yards (230 m) in front of them. At midnight, the German’s sent out a patrol and at 12:30 a.m., bombarded the British lines for twenty minutes. They then began a second bombardment from 1:30 a.m. until zero hour. The German bombardment then increased, when the British preliminary bombardment began and increased again when the attack started. The 11th EYR were laying out in the open, under a heavy bombardment, for over two hours. There were few British casualties, but the shelling caused considerable confusion, with A and D companies of the 11th EYR companies unable to form into their attacking positions.

The 13th East Yorkshire Diary records “Our barrage started at 3.45am advancing at a rate of 100 yards, every four minutes and the Battalion followed 50 yards behind the barrage. It was dark, from the smoke and dust caused by our barrage, and the hostile barrage, also the fact that we were advancing on a dark wood made it impossible to see when our barrage lifted off the German trench. Consequently the Hun had time to get his machine guns up. Machine guns were firing from within the wood from trees, as well as from the front trench, nevertheless the men went forward, attacked and were repulsed. Officers and NCO’s, reformed their men in No Man’s Land, under terrific fire and attacked again, and again were repulsed. Some even attacked a third time, some isolated parties got through the wood to OppyVillage and were reported there by aeroplanes at 6am. These men must have been cut off and surrounded later. The Battalion was so scattered and the casualties had been so heavy that it was decided to consolidate the only assembly trench we had when the battle started.” At 10pm the battalion was finally relieved by the 11th East Lancs and retired back to camp for a short rest. The 12th EYR, were also spotted moving up to their assembly trench and were heavily bombarded. Their War Diary writes: “The assembling took place in brilliant moonlight over quite unknown country and with four guides (from the 13th EYR). The enemy evidently saw the troops assembling and put up an intensive barrage followed by another one later. This considerably distinguished things and at zero hour, the blackest part of the night, the troops moved forward to the attack.” The first wave of the 12th EYR entered the German front line trench, which was strongly held, the second wave followed, but was forced to withdraw and eventually the first wave was beaten back out of the enemy line. Under heavy shell fire the 12th EYR to withdraw to their original assembly trench, where they remained all day, under heavy shelling and machine gun fire. They were later relieved during the night, on the 3rd/4th May, by the East Lancashire Regiment.

The 10th EYR also suffered a “tremendous” barrage on their assembly-positions, just before zero hour, which caused much disorganisation. The darkness in this area was increased by Oppy Wood itself and meant that the infantry could not see their barrage lift. The 10th EYR, on the right found areas of uncut wire and lost many casualties when they bunched up at the gaps, before reaching the wood. All four company commanders were wounded and the smoke and dust made it impossible to see what was going on at the flanks, and indeed obscured the objectives. The struggle to secure the German first line meant that the allied barrage had moved far ahead of the small parties that penetrated the German front trenches. A considerable number of men from the 10th EYR got into and beyond the first German line, some even penetrated OppyVillage itself. One gallant soldier even brought back eight German prisoners single handed. However it was impossible to get forward to consolidate the line. Survivors from the 10th EYR eventually withdrew to the original assembly trench where they started. Many troops were then cut off and captured, or forced back with many casualties. Many of the troops were stranded in ‘No Man’s land’ and had to wait all day under fire from snipers, machine-guns and artillery until nightfall, before completing the retirement. The 10th EYR war diary found it difficult to give an accurate account of the battle. “A considerable number of men undoubtedly crossed the German line and got some way forward and possibly in places reached the first objective.” It was discovered after the war that the majority of the 10th Hull Commercials, who had been taken prisoner during the attack, had actually advanced as far as Oppy village itself.

Hull Casualties

The official figures from Battalion Diary records, report that the ‘Hull Commercials’ (10th EYR battalion) went into the attack with 16 Officers and 484 Other Ranks. Their losses were: 13 Officers and 223 Other Ranks. At least 69 men were killed on the 3rd May with an unknown number dying of wounds later. The 11th EYR suffered at least 56 fatalities on the 3rd May.

The 12th EYR reported two Officers and seven other ranks killed, 150 other ranks missing and one Officer and 127 other ranks wounded, plus one Officer dying of wounds. The ‘Soldiers died in the Great War’ records, list 81 other ranks killed in action on the 3rd May with the 12th EYR. The losses suffered by the 12th EYR, were so great, that they resulted in it being reformed into only two companies. The remnants of A & C companies were attached to the 10th EYR and the remains of Companies B and D were sent to the 11th EYR. Although the attack on Oppy Wood was repulsed with many British casualties, the operations did succeed in diverting German attention from the French front.

CWGC records show 223 men from the 10th, 11th, 12th & 13th East Yorkshire Regiment, died at Oppy Wood, on the 3rd May 1917. Another 53 men from the 8th EYR, died on the same day, attacking the village of Monchy, ten miles away from Oppy.

At least 123 of these 276 men, or 44.5% have a known Hull connection. Another 29 Hull men, also died on the 3rd May 1917, fighting for other regiments. This meant a total of153 Hull men were killed on the 3rd May 1917. They included 17 men from the 8th EYR, 44 from the 10th EYR, 30 from the 11th EYR, 29 from the 12th EYR and 3 from the 13th EYR, all killed on the 3rd May 1917.

There would be many others who later died of wounds received on this day.

The CWGC, records that 580 men of the East Yorkshire regiment died during May and June 1917, and 7,815 men from the East Yorkshire regiment killed in the war. Many of these men would have come from Hull and the East Riding, as seen by cross checking CWGC records, Soldiers Died records which show enlistment areas and the addresses of the dead compiled on this website.

Cadorna Trench Raid

The Hull Pals later carried out a successful raid on Cadorna Trench on the 23rd and 24th June 1917. The 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th EYR’s each supplied two Officers and 50 other ranks for the raid which was led by Lt, Col., Ferrand from the 11th EYR. The raid was on a 40 yard front, with 50 yards between each battalion that attacked with rifle and bombing sections. Zero Hour was 10.20pm with a heavy bombardment of the German trench, during which the raiders left their position in two lines. Immediately as the barrage lifted, the raiders rushed the German first and second lines. The raid captured 200 prisoners and killed some 280 enemy, destroying dugouts and machine guns on the way. The raid lost 24 men, including Captain Saville, Lieutenant Wright and 2/Lieutenants Cliff and Oliver killed. Another 16 men were killed in the raid with four dying of wounds later. Another 28 men returned from the raid wounded. Sergeant Marritt won the DCM, but was killed on the raid. Oppy Wood was eventually captured on the 28th June 1917, with the East Yorkshires offering assistance. The 10th EYR formed the reserve Brigade, the 11th EYR held the front line with two companies and the 13th EYR was used for carrying parties.

Total Casualties

On 3 May, the 31st Division lost 1,900 casualties in the attack on Oppy Wood. The 2nd Division composite brigade had 517 losses, which left the division “bled white” with a “trench strength” of only 3,778 men. The Hull Commercials(10th battalion) went into the attack with 16 Officers and 484 Other Ranks. Their losses were: 13 Officers and 223 Other Ranks. The 11th and 12th Battalions, which also numbered men from Hull in their ranks, had similar losses. On 8 May, the 5th Bavarian Division lost 1,585 casualties in the counter-attack at Fresnoy. In the attack of 28 June the 31st Division lost 100 men and the 5th Division casualties were 352 men. Oppy wood was eventually captured on the 28th June 1917. The 10th EYR were held in reserve, the 11th EYR occupied the front line trenches and the 13th EYR were used as carrying parties.

Commemoration

* The units which attacked Oppy Wood were awarded the battle honour Oppy. A wood on the outskirts of North Hull, is named Oppy, as a War memorial to the Hull Pals involved in the battle on the 3rd and 4th May, 1917.

* On the 16th October 1932, the people of Hull and the Commune of Oppy, unveiled a permanent memorial at the scene of the battle. The ground of which the memorial stands was donated by the Vicomte and Vicomtesse du Bouexic de la Driennays in memory of their 22 year old son Pierre, an NCO of the French 504th Tank Regiment, who was killed in action at Guyencourt on 8 August 1918.

* Oppy Wood, was also immortalised in paint, by war artist John Nash. It is held at the Imperial War Museum (reference ART 2243) and is entitled “Oppy Wood, Evening, 1917“. It is one of a series of paintings commissioned by the British War Memorial Committee set up by the Ministry of Information early in 1918 and is 2 metres high and wide. The lower half of the composition has a view inside a trench with duckboard paths leading to a dug-out. Two British infantrymen stand to the left of the dug-out entrance, one of them on the firestep looking over the parapet into No Man’s Land. There is a wood of shattered trees littered with corrugated iron and planks at ground level to the right of the composition. The sky stretches above in varying shades of blue with a spectacular cloud formation framing a clear space towards the top of the composition.

The magnificent Oppy memorial to the men of Kingston-upon-Hull and all local units, who gave their lives in the Great War: Many of the casualties of 31st Division, who died at Oppy, were from the Hull area.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

THE GALLIPOLI CAMPAIGN – The 6th East Yorkshire Regiment -Tekke Teppe- 9th August 1915.

The Gallipoli Peninsula runs in a south-westerly direction into the Aegean Sea between the Hellesport (now known as the Dardanelles) and the bay of Melas, which today is known as Saros Bay. At the time of the First World War, this narrow sea strait was a direct route to the Russian Empire, but was controlled by the Turkish Ottoman Empire, allied to Germany. In an attempt to break the deadlock on the Western Front, the Allies launched an ambitious attack on Gallipoli Peninsular on the 25th April 1915. They hoped that capturing the Dardanelles Straits would help supply Russia, defeat Turkey and encourage Greece and Bulgaria to join the allies in the war.

The Gallipoli Peninsula runs in a south-westerly direction into the Aegean Sea between the Hellesport (now known as the Dardanelles) and the bay of Melas, which today is known as Saros Bay. At the time of the First World War, this narrow sea strait was a direct route to the Russian Empire, but was controlled by the Turkish Ottoman Empire, allied to Germany. In an attempt to break the deadlock on the Western Front, the Allies launched an ambitious attack on Gallipoli Peninsular on the 25th April 1915. They hoped that capturing the Dardanelles Straits would help supply Russia, defeat Turkey and encourage Greece and Bulgaria to join the allies in the war.

The allies invaded the Gallipoli Peninsular at several beaches. They were met by stiff Turkish resistance, which confined them to narrow beachheads. The Campaign fighting was fierce, attritional and largely static. The first two weeks alone at Gallipoli, saw a higher rate of allied casualties than the Battle of the Somme, when measured as a percentage of those committed. Forced to dig in around the shorelines, the Allies spent the next eight months trying to capture the high ground and break free from the Peninsular. Eventually, the Allies were forced to withdraw from Gallipoli on the 9th January 1916. The eight month Gallipoli Campaign was a famous Turkish victory, costly to both sides.

The Allied campaign was plagued by ill-defined goals, poor planning, insufficient artillery, inexperienced troops, inaccurate maps and intelligence, overconfidence, inadequate equipment and logistics, and tactical deficiencies at all levels. Geography also proved a significant factor with the Turks holding the higher ground. Over 131,000 men were killed during the 8 month Gallipoli Campaign. The Allies lost some 250,000 men, including 140,000 men through disease. Turkish casualties were estimated to be at least 280,000, with 86,000 killled.

The Allied campaign was plagued by ill-defined goals, poor planning, insufficient artillery, inexperienced troops, inaccurate maps and intelligence, overconfidence, inadequate equipment and logistics, and tactical deficiencies at all levels. Geography also proved a significant factor with the Turks holding the higher ground. Over 131,000 men were killed during the 8 month Gallipoli Campaign. The Allies lost some 250,000 men, including 140,000 men through disease. Turkish casualties were estimated to be at least 280,000, with 86,000 killled.

Gallipoli is best remembered for forging the National identity of Australia and New Zealand who suffered severely there, and for the remarkable evacuation of the Peninsular, which was achieved with the loss of only one life.

Links The Gallipoli Campaign http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallipoli_Campaign

8 things about Gallipoli http://www.history.com/news/8-things-you-may-not-know-about-the-gallipoli-campaign?cmpid=Social_FBPAGE_HISTORY_20150425_172975093&linkId=13760087

The Gallipoli campaign has been keenly debated over the last century. Some believe it was a poorly planned exercise that failed in Whitehall, long before any serviceman set foot on the peninsular. Others argue that the campaign could have been successful, but may have made little difference to the main struggle on the Western Front.

We can only speculate. However, history has largely overlooked how close ‘D’ company and HQ Battalion, of the 6th East Yorkshire Regiment, came to winning the campaign on the 8th and 9th Aug 1915. They failed (despite claims otherwise). The following is an interesting and little known episode in the Gallipoli story.

8th – 9th August 1915 – The 6th East Yorkshire Assault on Tekke Tepe Hill

Men of the 6th East Yorkshire Pioneers,in 1915, who served at Gallipoli.

Tekke Tepe, is a hill about 800ft in height, in the centre of a series of ridges disposed, roughly in the shape of a horseshoe and enclosing Suvla Bay. General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, maintained that capturing this hill was crucial to succeed at Gallipoli. The 6th East Yorkshire Battalion landed at Gallipoli in the early hours of the 7th August 1915, with 22 Officers and 750 other ranks. (Three Officers and 153 men had been left in reserve at Imbros).

Their attack on Tekke Tepe, is vividly recorded in the 6th (Pioneer) Battalion East Yorkshire War Diary, which is with the 11th Divisional Diaries. (This diary is easy to miss as it is not part of the line Battalion War Diary bundles. It is included in the Division papers, as the Pioneers were technically Divisional troops, although it seems they were attached to the 32nd Brigade for this operation). Capt. V Kidd, Adjutant of the 8th Battalion Duke of Wellington‘s Regt (West Ridings), also recorded the event in his personal account, which is an appendix to the 8th Battalion War Diary notes. Also the 6th Battalion York & Lancs. Regiment War Diary, records the Turks’ attack over Tekke Tepe.

8th Aug 1915. Orders were received to join the 32nd Brigade with the WEST YORKS on our left, to attack and hold a position running from CHOCOLATE HILL to SULAJIK 105 C 6. The records of these orders have been lost. The Battalion advanced B [Coy] on the left under Major, BRAY, D [Coy] on the right under Capt GRANT, C [Coy] in second line and A [Coy] in reserve. Lt Col, MOORE advanced

with the 1st line. At first no opposition was met with, but occupying the ridge which joins up with CHOCOLATE HILL and was about W by S from ANAFARTA SAGIR heavy firing was encountered. (Margin: Ref to ANAFARTA SAGIR sheet 1:20,000 Gallipoli Map 105 C 6) Capt ROGERS was killed and shortly afterwards Major, ESTRIDGE was wounded in the arm.  The Turks employed numerous snipers and shot particularly at our men as they went for water at a well. Parties were sent out, but were unable to find them. The position was entrenched on the reverse slope during the day and further forward during the night. Two officer’s patrols were sent out during the evening: At about11:30 pm orders were received for the Battalion to retire to the points held by the WEST RIDING Regt and to occupy and improve a Turkish trench there. 11:30 pm. The orders have been lost. The men were tired and exhausted and short of water moving often in the dark led to equipment being mislaid.

The Turks employed numerous snipers and shot particularly at our men as they went for water at a well. Parties were sent out, but were unable to find them. The position was entrenched on the reverse slope during the day and further forward during the night. Two officer’s patrols were sent out during the evening: At about11:30 pm orders were received for the Battalion to retire to the points held by the WEST RIDING Regt and to occupy and improve a Turkish trench there. 11:30 pm. The orders have been lost. The men were tired and exhausted and short of water moving often in the dark led to equipment being mislaid.

9th Aug 1915. We found the West Riding Regiment in a vacant Turkish Trench at about 1:30 am. After some confusion getting the men into the trench in the dark, orders (lost) were received at 3:30 a.m. (late in reaching us) to deliver an attack (orders lost) on TEKKE TEPE (Sheet 119 O2) the West Riding Regt was to attack KAVALA TEPE (Sheet 119 C7) on our left. The men were at this stage in a state of extreme exhaustion and hunger. The Battalion moved northwards out of the trench in the following order D, C, B, A after passing SULAJIK we took a NE route crossing the dry beds of the streams.

Verbal orders had been given by Lt Col Moore that in the attack D and B Companies should form the first line (D on the left, B on the right) A Coy (Capt WILLATS) the second line and C Coy (now under Capt PRINGLE) the reserve. LtCol, MOORE was with D Coy. The other three companies due to the extreme exhaustion of the men and absence of explicit orders failed to keep in touch with D Coy who proceeded to advance up the lower slopes of the hill without waiting for B Coy to come into position on their right or for the other two companies to get into place. D Coy with LtColMOORE and 2 Lt STILL (Acting Adjutant) and HQ party seemed to have encountered no opposition at first. It was only when they were up the first shoulder (Sheet 119 L4) that the strength of the enemy was disclosed. Fire was poured in from concealed Turkish trenches and our men were unable to hold their ground. There was considerable confusion due to the rapid advance of D Coy and the fact that the other Companies had lost touch. D Coy suffered heavily. Capt GRANT had been wounded in the hand early in the engagement – Lt Col MOORE, 2 Lt STILL, Capt ELLIOTT, Lt RAWSTORNE, 2 Lt WILSON were all missing when what remained of the Coy fell back. A general retirement took place during which there was much mixing of units due to the Battalion failing to keep its formation. After two other stands had been made in conjunction with the West Riding Regt a line was eventually taken up along a line running N from (Sheet 118 V6). Reinforcements came up here and about 13:00 the Battalion was relieved and ordered to concentrate at the cut on A Beach (Sheet 104 B1). All orders and dispatches relating to these are lost as the orderly who carried them is missing……[A long list of Officer casualties follows] Other Ranks: Killed 20, Wounded 104, Wounded and Missing 28, Missing 183.This night the battalion bivouacked on ‘A’ Beach near the cut.” The withdrawal of the East Yorkshires of the night of 8th August was difficult. There was no moon and it was pitch dark. It was almost impossible to find equipment and assemble the battalion quickly to move off to Sulajik. All the time, the Turks continued their fire on theEast Yorkshire, while they moved back and reached the position in the early hours. The East Yorkshire soldiers on arrival at 1.30am, dropped with exhaustion. Between 3 and 3.30am, all Company Commanders were suddenly ordered to report to the Colonel. They were told that the 6th East Yorkshire Regiment had received orders to seize the very high hill above Anafarta (Tekke Tepe).

The West Ridings would attack another hill on the left (Kavak Tepe). As the orders had arrived late, the battalion had to move off immediately. The men in a state of exhaustion, thirsty and hungry had to be pulled out of their trenches. Colonel HGA Moore started off with HQ and D companies. When the three remaining companies assembled they found Colonel Moore, their Commanding Officer had gone ahead. In crossing the open space between the trenches at Sulajik and the foot of the hill, little or no opposition was encountered. Two officers of the 67th Field Company Royal Engineers, Major F.W. Brunner and Lt. V.Z. Ferranti accompanied Lt Col. Moore. Lt Ferranti was ordered to wait and follow up with the next company of East Yorkshires that came along. The group split into three parties Col Moore., Maj. Brunner and 2 Lt Still, with one party, Capt. Steel with another and Capt.

Elliott with the third. As they reached the lower slopes of the hill north of Baka Baba, the rifle fire from the snipers became more insistent. They carried on up Tekke Tepe, the casualties becoming more serious. Major Brunner was killed and many others shot down. The survivors, Col. Moore and 2nd Lt. Still leading, reached the summit along with Capt., Elliot, Lt., Rawstone and between 12 and 30 men. They were cut off by the advancing Turks and the survivors, five in number, including Mr. Still, were captured.

Elliott with the third. As they reached the lower slopes of the hill north of Baka Baba, the rifle fire from the snipers became more insistent. They carried on up Tekke Tepe, the casualties becoming more serious. Major Brunner was killed and many others shot down. The survivors, Col. Moore and 2nd Lt. Still leading, reached the summit along with Capt., Elliot, Lt., Rawstone and between 12 and 30 men. They were cut off by the advancing Turks and the survivors, five in number, including Mr. Still, were captured.

This little party of East Yorkshire men and Engineers achieved the brilliant feat of reaching a position, farther east on the heights above Suvla Bay than any other troops in the entire campaign. Of the 750 men in the 6th (Pioneer) East Yorkshire Battalion, 347, or roughly 46% had become casualties in just 3 days. Officer casualties were 15, or 75% of those who landed on 7th August. They included two Officers killed in action; five wounded; six ‘Missing in Action’ and 2 ‘Wounded and Missing’. Most of those ‘Missing in Action’ at Gallipoli were actually killed. Searching this website shows that 47 men, killed with the 6th Yorkshires came from Hull, and ten others died on the 9th August 1915 at Suvla Bay, fighting for New Zealand, the West Ridings and other regiments. After the War, all captured British Officers were required to make a written statement to the War Office, about the events surrounding their capture. Capt R D Elliott, 6th Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment captured at Tekke Tepe recounted how they reached the top of hill. Another account by Lieutenant, John Still wrote. “About thirty of us reached the top of hill, perhaps a few more. And when there were about twenty left we turned and went down again. We had reached the highest point and furthest point that British forces from SuvlaBay were destined to reach. But we naturally knew nothing of that.

This little party of East Yorkshire men and Engineers achieved the brilliant feat of reaching a position, farther east on the heights above Suvla Bay than any other troops in the entire campaign. Of the 750 men in the 6th (Pioneer) East Yorkshire Battalion, 347, or roughly 46% had become casualties in just 3 days. Officer casualties were 15, or 75% of those who landed on 7th August. They included two Officers killed in action; five wounded; six ‘Missing in Action’ and 2 ‘Wounded and Missing’. Most of those ‘Missing in Action’ at Gallipoli were actually killed. Searching this website shows that 47 men, killed with the 6th Yorkshires came from Hull, and ten others died on the 9th August 1915 at Suvla Bay, fighting for New Zealand, the West Ridings and other regiments. After the War, all captured British Officers were required to make a written statement to the War Office, about the events surrounding their capture. Capt R D Elliott, 6th Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment captured at Tekke Tepe recounted how they reached the top of hill. Another account by Lieutenant, John Still wrote. “About thirty of us reached the top of hill, perhaps a few more. And when there were about twenty left we turned and went down again. We had reached the highest point and furthest point that British forces from SuvlaBay were destined to reach. But we naturally knew nothing of that.

General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, wrote in his War Diary, that Tekke Tepe was the key hill, overlooking Suvla Bay. He believed British troops had actually reached the summit of the hill on August 9, and that, had they been given proper support, victory was in sight. However, until 1923 he had no definite evidence to confirm his belief. In October 1923, he received a letter printed in The Times, (on 30th October 1923), from Mr. John Still, a tea planter in Ceylon, who had been adjutant of the 6thBattalion East Yorkshire Regiment, a unit of the 32 Brigade, during the Suvla operations. He gave details of his own experiences on Tekke Tepe as follows:-.

“I was the only officer on that hill who had spent years in jungle and on hills and was in consequence able to appreciate things accurately. We had been ordered to take up that position on the map and we took it up. I fixed our exact position by prismatic compass. We fought all day there and had a good few casualties including two officers (or three), and then we were taken off again at night “because the regiments to right and left of you have not been able to get up”. That was the night of August 8. On our right were a Sergeant and two men only of another regiment, lost and re-found by us. I forget their unit, but I can still see the identifying mark on their backs in my mind’s eye: it was a sort of castle in yellow.

Beyond them there was a gap right away to Chocolate Hill. On our left was not as you state another regiment, but only a weak half company of the West Yorkshires with two officers of whom one was killed, and the other – Davenport– severely wounded. And this left us in the air. Your orders given to General Stopford at 6pm never reached us on Scimitar Hill. Why? They knew where we were, for I was in touch by day with Brigade H.Q. signalers on Hill 10 or close to it. By night I lost contact for both my lamps failed me. As you justly say, anyone with half an eye could see Tekke Tepe was the key to the whole position. Even I, a middle-aged amateur who had done a bit of big game shooting and knocking about saw it at once. We reconnoitered it, sent an officer and my signaler corporal to climb it, and got through to Brigade H.Q. the message giving our results.

Beyond them there was a gap right away to Chocolate Hill. On our left was not as you state another regiment, but only a weak half company of the West Yorkshires with two officers of whom one was killed, and the other – Davenport– severely wounded. And this left us in the air. Your orders given to General Stopford at 6pm never reached us on Scimitar Hill. Why? They knew where we were, for I was in touch by day with Brigade H.Q. signalers on Hill 10 or close to it. By night I lost contact for both my lamps failed me. As you justly say, anyone with half an eye could see Tekke Tepe was the key to the whole position. Even I, a middle-aged amateur who had done a bit of big game shooting and knocking about saw it at once. We reconnoitered it, sent an officer and my signaler corporal to climb it, and got through to Brigade H.Q. the message giving our results.  I sent it myself. The hill was then empty. Next morning you saw or heard that troops had actually reached the top of Tekke Tepe. Yes they had. A worn and weak company, D Company, of my regiment, together with my Colonel (Moore). Major Brunner, of the Royal Engineers., and myself started up that hill. About thirty got to the top: of them five got down again to the bottom, and of those three lived to the end of the war. I was one of them. You wonder why we did not ‘dig in’ (pages 78 and 79 of your Volume II) as we had lots of time. There, Sir is where that war was lost. You sent a Brigade at that empty hill on the afternoon of the 8th. Actually, owing to staff work being so bad, only a battalion received orders to attack, and they did not receive those orders until dawn on the 9th. I received them myself as adjutant. The order ran to this effect: “The C.-in-C. considers this operation essential to the success of the whole campaign”.

I sent it myself. The hill was then empty. Next morning you saw or heard that troops had actually reached the top of Tekke Tepe. Yes they had. A worn and weak company, D Company, of my regiment, together with my Colonel (Moore). Major Brunner, of the Royal Engineers., and myself started up that hill. About thirty got to the top: of them five got down again to the bottom, and of those three lived to the end of the war. I was one of them. You wonder why we did not ‘dig in’ (pages 78 and 79 of your Volume II) as we had lots of time. There, Sir is where that war was lost. You sent a Brigade at that empty hill on the afternoon of the 8th. Actually, owing to staff work being so bad, only a battalion received orders to attack, and they did not receive those orders until dawn on the 9th. I received them myself as adjutant. The order ran to this effect: “The C.-in-C. considers this operation essential to the success of the whole campaign”.  The order was sent out on the late afternoon of the 8th, when we were on Scimitar Hill. It reached us at dawn on the 9th in a Turkish trench at Sulejik. In the meanwhile, for those hours more precious to the world than we even yet can judge, the Brigade Major was lost! Good God why didn’t they send a man who knew the country? He was lost, lost, lost and it drives one almost mad to think of it. Excuse Me. Next morning (from the order) at dawn on the 9th you saw some of our fellows climbing cattle tracks. You don’t place them exactly where I think you really saw them, but as I know, there were none just precisely where you say you saw them, I am pretty certain it was us you saw from the ship, only we were half a mile north of where you describe.Then we climbed Tekke Tepe.Simultaneously the Turks attacked through the gap from Anafarta.

The order was sent out on the late afternoon of the 8th, when we were on Scimitar Hill. It reached us at dawn on the 9th in a Turkish trench at Sulejik. In the meanwhile, for those hours more precious to the world than we even yet can judge, the Brigade Major was lost! Good God why didn’t they send a man who knew the country? He was lost, lost, lost and it drives one almost mad to think of it. Excuse Me. Next morning (from the order) at dawn on the 9th you saw some of our fellows climbing cattle tracks. You don’t place them exactly where I think you really saw them, but as I know, there were none just precisely where you say you saw them, I am pretty certain it was us you saw from the ship, only we were half a mile north of where you describe.Then we climbed Tekke Tepe.Simultaneously the Turks attacked through the gap from Anafarta.  Their attack cut in behind D Company and held back the rest of the battalion who fought in the trench, with the Duke of Wellington‘s on their left. We went on, and, as I said, not one of us got back again. A few were taken prisoner. I was slightly wounded, and stayed three years and three months as a prisoner. Later that morning we who survived were again taken up Tekke Tepe by its northern ravine on the west side. Turkish troops were simply pouring down it and the other ravines. On the top of Tekke Tepe were four field guns camouflaged with boughs of scrub oak, and a Brigade H.Q. was just behind the ridge. I had a few minutes conversation there with the Turkish Brigadier in French. But I am coming home on leave in March or April next.

Their attack cut in behind D Company and held back the rest of the battalion who fought in the trench, with the Duke of Wellington‘s on their left. We went on, and, as I said, not one of us got back again. A few were taken prisoner. I was slightly wounded, and stayed three years and three months as a prisoner. Later that morning we who survived were again taken up Tekke Tepe by its northern ravine on the west side. Turkish troops were simply pouring down it and the other ravines. On the top of Tekke Tepe were four field guns camouflaged with boughs of scrub oak, and a Brigade H.Q. was just behind the ridge. I had a few minutes conversation there with the Turkish Brigadier in French. But I am coming home on leave in March or April next.  May I have the honour of meeting you and going over it on the map?I think much might be cleared up that was still obscure when you wrote your book. There are one or two things one prefers not to write.Please let me know your wishes in this matter. I loved your book and I want to do any small thing possible to complete your picture. Yours truly (Signed) JOHN STILL, Victoria Commemoration Buildings, Nos: 40 and 41 Ward Street, Kandy, Ceylon Sept 19.

May I have the honour of meeting you and going over it on the map?I think much might be cleared up that was still obscure when you wrote your book. There are one or two things one prefers not to write.Please let me know your wishes in this matter. I loved your book and I want to do any small thing possible to complete your picture. Yours truly (Signed) JOHN STILL, Victoria Commemoration Buildings, Nos: 40 and 41 Ward Street, Kandy, Ceylon Sept 19.

Second Lieutenant, James Theodore Underhill, was a 22 year old, adjutant serving with the 6th East Yorkshire Battalion at Galipolli and was the Signaler at Tekke Tepe. His letter to the Times, published 14thFebruary 1925, recounts the following”….Being a qualified land surveyor, and experienced in the use and construction of maps and the knowledge of the country, I was well able to keep notes of our positions and was the officer mentioned in your letter who took the patrol up Tekke Tepe. In fact I still have your signal corporal’s field glasses which I took from him while on the hill, my own being smashed by a rifle bullet whilst using them on this patrol. My report disagrees with your letter in a few minor details – for instance while on Scimitar Hill, the 9th West Yorkshires were on our left, as I was actually speaking with their officers on their own right flank, but they were withdrawn before us, God knows why. Again, while you say Tekke Tepe was not occupied, it was held very lightly by patrols. We ran into two of them before reaching the top; out of one we bagged two Turks, the other escaped us. There were also three short lengths of partially dug trenches unoccupied while we were there, but showing signs of most recent occupation. Further, you say that the Turks came in behind D Company and the rest of the battalion fought in the trench. This is not quite right. We had advance fully 1500 yards (and I was with the rear company “B”) before we encountered the Turks. When we did, it was a ‘free for all’ bayonet affair, with the Turks outnumbering us about three to one. I saw nothing of the West Yorkshires as you mention, but the West Ridings who were to have supported the Brigade!!! attack were present. However, my report and your letter agree in the great fundamental point, this, that Tekke Tepe should have been taken on the evening of August 8. That this could and would have been done had there not been a lamentable failure of the Staff, I think goes unquestioned by those of us who had an accurate knowledge of the conditions; it was the loss of the Gallipoli campaign. I am even of the opinion that, that had the Staff work not been so rotten, and that had the attack in the early morning of August 9 been by three battalions instead of us alone, it might have been successful. If you remember, the attack was to have been a brigade affair, three battalions in attack with one in support. The supports (the West Ridings) were there, but where the other two battalions were, God alone knows. I think all of Kitchener’sArmy who took part in this landing and the following few days felt it intensely that they were blamed by the Staff for the failure on the grounds of being green troops. Compared with later experiencesin France, the 11thand 10thDivision fought as well as any troops ever did, be they Regulars or otherwise, and I am sure that those of us who had the honour to belong to either the 11thor 10thDivisions feel grateful to you for coming out plainly and placing the blame where it so justly belongs.” *

Second Lieutenant, James Theodore Underhill, was a 22 year old, adjutant serving with the 6th East Yorkshire Battalion at Galipolli and was the Signaler at Tekke Tepe. His letter to the Times, published 14thFebruary 1925, recounts the following”….Being a qualified land surveyor, and experienced in the use and construction of maps and the knowledge of the country, I was well able to keep notes of our positions and was the officer mentioned in your letter who took the patrol up Tekke Tepe. In fact I still have your signal corporal’s field glasses which I took from him while on the hill, my own being smashed by a rifle bullet whilst using them on this patrol. My report disagrees with your letter in a few minor details – for instance while on Scimitar Hill, the 9th West Yorkshires were on our left, as I was actually speaking with their officers on their own right flank, but they were withdrawn before us, God knows why. Again, while you say Tekke Tepe was not occupied, it was held very lightly by patrols. We ran into two of them before reaching the top; out of one we bagged two Turks, the other escaped us. There were also three short lengths of partially dug trenches unoccupied while we were there, but showing signs of most recent occupation. Further, you say that the Turks came in behind D Company and the rest of the battalion fought in the trench. This is not quite right. We had advance fully 1500 yards (and I was with the rear company “B”) before we encountered the Turks. When we did, it was a ‘free for all’ bayonet affair, with the Turks outnumbering us about three to one. I saw nothing of the West Yorkshires as you mention, but the West Ridings who were to have supported the Brigade!!! attack were present. However, my report and your letter agree in the great fundamental point, this, that Tekke Tepe should have been taken on the evening of August 8. That this could and would have been done had there not been a lamentable failure of the Staff, I think goes unquestioned by those of us who had an accurate knowledge of the conditions; it was the loss of the Gallipoli campaign. I am even of the opinion that, that had the Staff work not been so rotten, and that had the attack in the early morning of August 9 been by three battalions instead of us alone, it might have been successful. If you remember, the attack was to have been a brigade affair, three battalions in attack with one in support. The supports (the West Ridings) were there, but where the other two battalions were, God alone knows. I think all of Kitchener’sArmy who took part in this landing and the following few days felt it intensely that they were blamed by the Staff for the failure on the grounds of being green troops. Compared with later experiencesin France, the 11thand 10thDivision fought as well as any troops ever did, be they Regulars or otherwise, and I am sure that those of us who had the honour to belong to either the 11thor 10thDivisions feel grateful to you for coming out plainly and placing the blame where it so justly belongs.” *

Some argue that the 6th East Yorkshire attack on Tekke Tepe (actually in effect only D Coy and Battalion HQ) never reached the summit on the 9th August. Also the Officers were mistaken when they said that they reached the summit or had made it up after the war to compensate for being taken Prisoner. Also as most of the East Yorkshires were killed or captured, all the official reports were compiled after the events, by persons who had not been present. The War diaries show very clearly that patrols sent by the 6th East Yorkshires on the 8th August (the day before) met with little opposition, but a later advance on the 9th August to exploit this opportunity by the 6th East Yorkshires, supported by the 8th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding) and 67 Coy Royal Engineers was too late. It was repulsed by Turkish reinforcements, with heavy loss to D Coy of the 6th East Yorkshires, who advanced without waiting for the remainder of the Battalion. However, the primary sources of Lieutenants John Still and James Underhill, who both were there at the time, claim that they did occupy Tekke Tepe. John Still was a 35 year old, tea planter, use to the hills of Ceylon and Underhill was a newly qualified land surveyor, aged 22. Both would have known if they had reached the top of Tekke Tepe. There was no collusion between these two men to make up their story. Lt., Stlll was captured and spent the rest of the war in Turkey. He believed he had been the only surviving Officer in the attack. Underhill although wounded in the chest, survived the war and then emigrated to Vancouver. If they did occupy Tekke Teppe, it would have been the furthest allied advance on the Peninsula, and if they had held this stategic position, the Gallipoli Campaign would have succeeded. After 100 years we can only speculate. It is perhaps best to concentrate on the bravery of the 6th (Pioneer) East Yorkshire Regiment, who stormed the hill with limited support in difficult conditions. These Pioneers were used in (arguably) the most important assault of the campaign. They were ably led, by Col Moore, (who had risen from the ranks) and were decimated within sight of their ultimate objective. Their attack was undermined by appalling planning and procrastination. There was no time for orders or battle preparation. It was a fragmented, uncoordinated attack, characterised by perhaps over-zealous leadership, tactical naivety, exhaustion and fatigue. (The men had to be kicked into action, from a state of near exhaustion). This superhuman effort resulted in failure, then denial and blame. The 6th East Yprkshire who had landed at Gallipoli in the early hours of the 7th August 1915, with 22 Officers and 750 Other ranks, had within 3 days, lost 15 Officers and 347 other ranks. Over 50 men from Hull died in Gallipoli on the 9th August 1915. The story of the 6th East Yorkshire at Tekke Tepe, is not a particularly well researched, or well understood part of the campaign, outside a few specialists, but it encapsulates everything in one small action that was wrong about Gallipoli.

The following recounts the progress of the 6Th East Yorkshires, after the Tekke Tepe attack.

21st August 1915 – the attack on Scimitar Hill

Wyrall’s “East Yorkshire Regiment in the Great War” shows that the 6th East Yorkshire Regiment had been in reserve from 10th to the 20th August at Nibrunesi Point where they had dug themselves in at the base of a cliff. On 20th August the 6thEast Yorkshires relieved the Northumberland Fusiliers in trenches South East of Chocolate Hill. They came under the orders of 34th Brigade who would attack “Hill W” the next morning.

The 6th Battalion were to dig in and support the Lancashire Fusiliers and the Dorset’s, who would attack the next morning. There was a delay due to lost orders and confusion, and the attack did not commence until 3pm on the 21st. When the Dorset’s and Lancashire’s left their trenches the 6th East Yorkshiresmoved forward to occupy these trenches. The Dorset’s and the Lancashire’s ran into stubborn resistance and so most of the 6th East Yorkshires were sent forward to support them. The 6th East Yorkshire‘s captured a Turkish trench in front of them and awaited relief. The 6th East York (Pioneers) had occupied Hill 70 (Scimitar Hill), next to W Hill the most vital of all the semicircle of heights overlooking Suvla Bay and were there only waiting for the brigade’s further advance upon W Hill or Anafarta Sagir, to both of which it is the key. They held this trench overnight, but it became impossible to hold the next morning (22nd August) as the number of Turks increased and they had no bombs.

Around 7.30 am the 6th East Yorkshires retreated to their original trenches and later that night they were relieved and moved back to their original reserve trenches at Nibrunesi point the following morning. The 6th East Yorkshire casualties by 22nd August 1915, included 26 Officers and 628 men. Officer casualties were 80% and other ranks 68%.

Around 7.30 am the 6th East Yorkshires retreated to their original trenches and later that night they were relieved and moved back to their original reserve trenches at Nibrunesi point the following morning. The 6th East Yorkshire casualties by 22nd August 1915, included 26 Officers and 628 men. Officer casualties were 80% and other ranks 68%.

20th October 1915

The War Diary for the 6th (Service) Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment (Pioneers) on 20th Oct 1915 is edited below. It was written in very feint pencil and just legible. The Battalion was scattered over a place known to the troops as ‘Piccadilly Circus’ or ‘Shrapnel Valley’ due to heavy Turkish shelling. There are no records of battle casualties, but the War Diary contains long lists of men admitted to hospital and lists of men who arrived in drafts. Notably most posted to D Coy – a stark reminder that D Coy was virtually wiped out on the lower slopes of Tekke Tepe on 9th August.

“Working Parties A Coy Piccadilly Circus, Div Head Quarters ^ well [illegible – above?] XI Signal Depot, Field Ambulance dugouts. B Coy 9th A.C [Army Corps] New Head Quarters, Park Lane, Holborn, Jephson’s Post Road (Oxford St). D Coy 9th A.C Head Quarters, 67th Coy RE – SW Mounted Brigade dugouts, Cannon Street. Two general road repairing parties under 2/Lieuts SIEBER and SCOTCHER. 2/Lieut HICKEY was wounded in the arm by shrapnel bullet whilst working near Piccadilly Circus & admitted into 35th Field Ambulance.”

Gallipoli 100 Years on – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-32456487

* (I am grateful to Edward Underhill who supplied the following information on his grandfather – 2nd Lt., James Theodore Underhill was born in Moseley, Staffordshire, 1892. His family emigrated to Canada in 1894 and he obtained his Land Surveyor’s qualification at McGill University (West) which was later to become the University of British Columbia. Upon the outbreak of the war, he gained his qualification as an Infantry Officer in January of 1915 at the Provisional School of Infantry in Vancouver, BC and subsequently travelled to England, having missed the opportunity to join the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). He was commissioned in March of 1915, joining the 6th (Service ) Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, as 2nd Lieutenant by the time of the actions around Teke Tepe. He was shot in the chest during the Gallipoli attack and wounded again in the right knee on 1/7/16 at Serre, serving with the 12th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. He later served with the Canandian 245th Siege Battery RGA. He lost two brothers in the war and returned to Vancouver, Canada after the war)

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

OPPY WOOD, 3rd May 1917 – The Hull Pals Attack

The Capture of Oppy Wood was an engagement, North East of Arras, between May and June 1917. The Germans were in possession of a fortified wood to the west of the village of Oppy, which overlooked British positions. The wood was 1-acre (0.40 ha) in area and contained many German observation posts, machine-guns and trench-mortars. The aim of the attack was to remove this defensive obstacle and divert German resources away from the main offensive, planned at Messines in early June 1917. In military terms, Oppy Wood was a diversionary attack, by the 92nd Brigade, of the 31st Division,during the Third Battle of the Scarpe (3–4 May). It was an attack on a half mile front, in unfavourable conditions, and against impenetrable German defences. It is also known as the Battle of Gavrelle. However, for the people of Hull, Oppy Wood, would be forever remembered as the place where the Hull Pals made their name. In fierce fighting around the village, Hull lost more men on the 3rd May 1917, than any other. The attack failed and the final casualties totalled 326.

The main British attacking forces in this battle were the 10th, 11th and 12th Battalions of the East Yorkshire Regiment, known as the ‘Hull Pals’. They advanced up a slope, in the dark, in four waves, over difficult terrain, illuminated by German rockets and Very Lights. They faced Oppy Wood, which was elaborately fortified, and defended by experienced German troops. They struggled forward over three belts of barb wire entanglements. Unable to keep pace with their barrage, and were exposed to murderous German machine gun fire. Despite this, the Hull Pals continued to advance. One company fought their way into Oppy village itself, while the rest were held up. After attacking three times, they were forced to withdraw under constant fire. During the action, 2nd-Lieut. John Harrison, of the 11th Battalion, silenced an enemy machine-gun post single handedly and was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Preparations for the attack on Oppy began on the 1st May 1917. Officers and NCO’s of the 10th and 13th EYR, went forward to check the assembly positions and returned next morning to issue equipment for the advance. At 11pm on the 2nd May, the 11th and 12th EYR Battalions started to move to their assembly positions. The 10th EYR moved at 11.30pm. Start time for the attack was to be 3.45am on the 3rd May, with the 10th EYR positioned on the right flank, the 11th EYR in the centre and the 12th EYR on the left flank, all opposite Oppy Wood. A preliminary bombardment by nine Field Artillery Brigades and the use of extra machine guns was expected to cut the barb wire, neutralise all German resistance and leave the trenches intact for the Pals to occupy. In reality, this failed to happen for a number of reasons.

1. On the 28th and 29th April, the Battle of Arleux had been fought on the same battleground and the 13th EYR had suffered a number of casualties. The assembly positions which had been heavily shelled, offered little cover and debris from that battle littered the ground, hindering coordinated movement. The 10th EYR Battalion history records that the assembly trenches were “barely four feet deep, with no communications to the rear, nor any means of contact to left or right.”

2. Oppy Wood was full of fallen trees and tangled branches which gave the enemy great cover. A long slope of 1,000m to the west, left the British field artillery at extreme range. This reduced its accuracy and largely failed to cut the enemy wire.

3. Oppy wood was a strongly defended position, guarded by experienced German soldiers. In front of Oppy Wood, lay a well organised trench system, protected by barb wire and good communications, which covered the Oppy wood and village from flanking attacks. The wood itself contained a large number of machine gun posts and all along the German lines, machine gun posts and mortars were well placed to repel any attack. The area was held by the 1st and 2nd German Guards, which the East Yorkshire Regimental history describes as, ‘some of the bravest of the enemy troops’. The Germans had strengthened the wood by developing defensive tactics learnt from the earlier Somme battles. The British had expected to encounter demoralised troops and thought that the creeping barrage would neutralise all resistance. However, some of the German wire at the south-western corner of the wood was uncut and rather than being shaken, the Germans were actually massing for a counter attack.

4. It was originally intended to make a night assault, to evade German machine-gun fire. However, the Third and First armies needed to attack in daylight and Douglas Haig enforced a compromise zero hour of 3:45 a.m. No preparations had been made for an advance at night, such as, putting out boards, luminous paint on the German wire, taking compass-bearings or organising intermediate objectives. Sunrise was not until 5:22 a.m. and it would not be possible to see objects in the dark, at 50 yards (46 m) until 4:05 a.m.

5. On the night of the attack, there was a full moon which did not set until sixteen minutes before the attack beagn. On many parts of the front, British troops assembling, were illuminated by the moon, exposing them to enemy fire. The 11th EYR war diary records “to get to the assembly positions, Companies had to go over the top of a rise within 1000 yards, with a moon low in the sky behind them.”

6. The German defenders saw the British infantry forming up in the moonlight, in an assembly trench just 250 yards (230 m) in front of them. At midnight, the German’s sent out a patrol and at 12:30 a.m., bombarded the British lines for twenty minutes. They then began a second bombardment from 1:30 a.m. until zero hour. The German bombardment then increased, when the British preliminary bombardment began and increased again when the attack started. The 11th EYR were laying out in the open, under a heavy bombardment, for over two hours. There were few British casualties, but the shelling caused considerable confusion, with A and D companies of the 11th EYR companies unable to form into their attacking positions.

The 13th East Yorkshire Diary records “Our barrage started at 3.45am advancing at a rate of 100 yards, every four minutes and the Battalion followed 50 yards behind the barrage. It was dark, from the smoke and dust caused by our barrage, and the hostile barrage, also the fact that we were advancing on a dark wood made it impossible to see when our barrage lifted off the German trench. Consequently the Hun had time to get his machine guns up. Machine guns were firing from within the wood from trees, as well as from the front trench, nevertheless the men went forward, attacked and were repulsed. Officers and NCO’s, reformed their men in No Man’s Land, under terrific fire and attacked again, and again were repulsed. Some even attacked a third time, some isolated parties got through the wood to OppyVillage and were reported there by aeroplanes at 6am. These men must have been cut off and surrounded later. The Battalion was so scattered and the casualties had been so heavy that it was decided to consolidate the only assembly trench we had when the battle started.” At 10pm the battalion was finally relieved by the 11th East Lancs and retired back to camp for a short rest. The 12th EYR, were also spotted moving up to their assembly trench and were heavily bombarded. Their War Diary writes: “The assembling took place in brilliant moonlight over quite unknown country and with four guides (from the 13th EYR). The enemy evidently saw the troops assembling and put up an intensive barrage followed by another one later. This considerably distinguished things and at zero hour, the blackest part of the night, the troops moved forward to the attack.” The first wave of the 12th EYR entered the German front line trench, which was strongly held, the second wave followed, but was forced to withdraw and eventually the first wave was beaten back out of the enemy line. Under heavy shell fire the 12th EYR to withdraw to their original assembly trench, where they remained all day, under heavy shelling and machine gun fire. They were later relieved during the night, on the 3rd/4th May, by the East Lancashire Regiment.

The 10th EYR also suffered a “tremendous” barrage on their assembly-positions, just before zero hour, which caused much disorganisation. The darkness in this area was increased by Oppy Wood itself and meant that the infantry could not see their barrage lift. The 10th EYR, on the right found areas of uncut wire and lost many casualties when they bunched up at the gaps, before reaching the wood. All four company commanders were wounded and the smoke and dust made it impossible to see what was going on at the flanks, and indeed obscured the objectives. The struggle to secure the German first line meant that the allied barrage had moved far ahead of the small parties that penetrated the German front trenches. A considerable number of men from the 10th EYR got into and beyond the first German line, some even penetrated OppyVillage itself. One gallant soldier even brought back eight German prisoners single handed. However it was impossible to get forward to consolidate the line. Survivors from the 10th EYR eventually withdrew to the original assembly trench where they started. Many troops were then cut off and captured, or forced back with many casualties. Many of the troops were stranded in ‘No Man’s land’ and had to wait all day under fire from snipers, machine-guns and artillery until nightfall, before completing the retirement. The 10th EYR war diary found it difficult to give an accurate account of the battle. “A considerable number of men undoubtedly crossed the German line and got some way forward and possibly in places reached the first objective.” It was discovered after the war that the majority of the 10th Hull Commercials, who had been taken prisoner during the attack, had actually advanced as far as Oppy village itself.

Hull Casualties

The official figures from Battalion Diary records, report that the ‘Hull Commercials’ (10th EYR battalion) went into the attack with 16 Officers and 484 Other Ranks. Their losses were: 13 Officers and 223 Other Ranks. At least 69 men were killed on the 3rd May with an unknown number dying of wounds later. The 11th EYR suffered at least 56 fatalities on the 3rd May.

The 12th EYR reported two Officers and seven other ranks killed, 150 other ranks missing and one Officer and 127 other ranks wounded, plus one Officer dying of wounds. The ‘Soldiers died in the Great War’ records, list 81 other ranks killed in action on the 3rd May with the 12th EYR. The losses suffered by the 12th EYR, were so great, that they resulted in it being reformed into only two companies. The remnants of A & C companies were attached to the 10th EYR and the remains of Companies B and D were sent to the 11th EYR. Although the attack on Oppy Wood was repulsed with many British casualties, the operations did succeed in diverting German attention from the French front.

CWGC records show 223 men from the 10th, 11th, 12th & 13th East Yorkshire Regiment, died at Oppy Wood, on the 3rd May 1917. Another 53 men from the 8th EYR, died on the same day, attacking the village of Monchy, ten miles away from Oppy.

At least 123 of these 276 men, or 44.5% have a known Hull connection. Another 29 Hull men, also died on the 3rd May 1917, fighting for other regiments. This meant a total of153 Hull men were killed on the 3rd May 1917. They included 17 men from the 8th EYR, 44 from the 10th EYR, 30 from the 11th EYR, 29 from the 12th EYR and 3 from the 13th EYR, all killed on the 3rd May 1917.

There would be many others who later died of wounds received on this day.

The CWGC, records that 580 men of the East Yorkshire regiment died during May and June 1917, and 7,815 men from the East Yorkshire regiment killed in the war. Many of these men would have come from Hull and the East Riding, as seen by cross checking CWGC records, Soldiers Died records which show enlistment areas and the addresses of the dead compiled on this website.

Cadorna Trench Raid

The Hull Pals later carried out a successful raid on Cadorna Trench on the 23rd and 24th June 1917. The 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th EYR’s each supplied two Officers and 50 other ranks for the raid which was led by Lt, Col., Ferrand from the 11th EYR. The raid was on a 40 yard front, with 50 yards between each battalion that attacked with rifle and bombing sections. Zero Hour was 10.20pm with a heavy bombardment of the German trench, during which the raiders left their position in two lines. Immediately as the barrage lifted, the raiders rushed the German first and second lines. The raid captured 200 prisoners and killed some 280 enemy, destroying dugouts and machine guns on the way. The raid lost 24 men, including Captain Saville, Lieutenant Wright and 2/Lieutenants Cliff and Oliver killed. Another 16 men were killed in the raid with four dying of wounds later. Another 28 men returned from the raid wounded. Sergeant Marritt won the DCM, but was killed on the raid. Oppy Wood was eventually captured on the 28th June 1917, with the East Yorkshires offering assistance. The 10th EYR formed the reserve Brigade, the 11th EYR held the front line with two companies and the 13th EYR was used for carrying parties.

Total Casualties

On 3 May, the 31st Division lost 1,900 casualties in the attack on Oppy Wood. The 2nd Division composite brigade had 517 losses, which left the division “bled white” with a “trench strength” of only 3,778 men. The Hull Commercials(10th battalion) went into the attack with 16 Officers and 484 Other Ranks. Their losses were: 13 Officers and 223 Other Ranks. The 11th and 12th Battalions, which also numbered men from Hull in their ranks, had similar losses. On 8 May, the 5th Bavarian Division lost 1,585 casualties in the counter-attack at Fresnoy. In the attack of 28 June the 31st Division lost 100 men and the 5th Division casualties were 352 men. Oppy wood was eventually captured on the 28th June 1917. The 10th EYR were held in reserve, the 11th EYR occupied the front line trenches and the 13th EYR were used as carrying parties.

Commemoration

* The units which attacked Oppy Wood were awarded the battle honour Oppy. A wood on the outskirts of North Hull, is named Oppy, as a War memorial to the Hull Pals involved in the battle on the 3rd and 4th May, 1917.

* On the 16th October 1932, the people of Hull and the Commune of Oppy, unveiled a permanent memorial at the scene of the battle. The ground of which the memorial stands was donated by the Vicomte and Vicomtesse du Bouexic de la Driennays in memory of their 22 year old son Pierre, an NCO of the French 504th Tank Regiment, who was killed in action at Guyencourt on 8 August 1918.

* Oppy Wood, was also immortalised in paint, by war artist John Nash. It is held at the Imperial War Museum (reference ART 2243) and is entitled “Oppy Wood, Evening, 1917“. It is one of a series of paintings commissioned by the British War Memorial Committee set up by the Ministry of Information early in 1918 and is 2 metres high and wide. The lower half of the composition has a view inside a trench with duckboard paths leading to a dug-out. Two British infantrymen stand to the left of the dug-out entrance, one of them on the firestep looking over the parapet into No Man’s Land. There is a wood of shattered trees littered with corrugated iron and planks at ground level to the right of the composition. The sky stretches above in varying shades of blue with a spectacular cloud formation framing a clear space towards the top of the composition.

The magnificent Oppy memorial to the men of Kingston-upon-Hull and all local units, who gave their lives in the Great War: Many of the casualties of 31st Division, who died at Oppy, were from the Hull area.