While fighting during WW1 spanned the globe, the Western Front was the primary focus of Britain’s war. The ‘Western Front’ marked the furthest German advances. It was a 400 mile battle line, extending from the North Sea coast at Nieuwpoort, to the Swiss border. The French held about 360 miles of this line and carried much of the war burden up to 1916, until Britain’s new Volunteer Army had been trained for action. Typically, the front line consisted of three individual trench lines about 100 meters apart, protected by belts of barb wire up, to 20 meters deep, and with positions for machine guns. Villages would be converted into fortresses and the cellars of houses fortified. In due course, a second defensive line, similar to the first, was dug three or four miles back, out of artillery range, so that a single attack could not break right through the defences. The Germans for most part occupied higher ground. Initially, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), held 20 miles of this 400 mile front in 1914, and by 1918 controlled over 120 miles of the Western Front. The Western Front was the principal and vital theatre of war, along which millions of men fought and died. From the 8.5 million men of the British Empire that enlisted, almost 5.5 million, served at some time on the Western Front. Against the German Army fought the allied armies of the British Commonwealth, France, Belgium and later the United States.

The German invasion of Europe in 1914, occupied 90% of Belgium, and 10 French regions. The resulting German-occupied territory controlled 11 million civilians, 64% of France’s pig iron production, 24% of its steel manufacturing, and 40% of France’s total coal mining capacity. This dealt a serious, but not crippling setback to French industry.

The war on the Western Front can be thought of as being in three phases:

1) a two month war of movement in 1914, as Germany attempted to capture France within the first 42 days and the Allies sought to halt it;

2) three and half years of costly siege warfare, as the entrenched lines proved impossible to crack (late 1914 to mid 1918), and finally,

3) a return to mobile warfare, when a series of German offensives, starting on the 21st March 1918, pushed back the British lines, but failed to break through. On the 16th July 1918, the Allies launched a counter offensive. Boosted by newly arrived American reinforcements, the Allies over the next 100 days recaptured all the lost ground.

The Western Front was characterised by prolonged attritional warfare, bloody battles and great loss of life. Most British soldiers died on the Western Front and the war in the trenches left tens of thousands of maimed soldiers and war widows. The unprecedented loss of life had a lasting effect on popular attitudes toward war, resulting later in an Allied reluctance to pursue an aggressive policy toward Adolf Hitler. Belgium suffered 30,000 civilian dead and France 40,000 (including 3,000 merchant sailors).

France initially led military events on the Western Front. France was fighting on their own soil and occupied most of the Western Front. However, the war’s Anglo-French coalition rarely existed harmoniously. Wrangling, suspicion, anger and subversion permeated the supposedly joint war effort. The balalnce of power shifted over time, slowly at first and later more quickly, from the French to the British and arguably, even later to the Americans. The disastrous Nivelle Offensive on 16 April 1917 and subsequent French mutinies meant Britain took a greater lead in the war.

The Western Front is often remembered for a ‘Christmas Truce’, and a football match, between opposing sides on Christmas Day 1914. It is estimated that some 30,000 troops, along some parts of the front line, met in ‘No Mans’ Land, to shake hands and exchange Christmas gifts. It was also an opportunity to bury the dead and spy on each other’s defences. There is some evidence that the British started some impromptu football matches, but the Germans mostly looked on, rather than took part. Generals on both sides soon halted this fraternization , by ordering the shelling of enemy positions. There were no further ‘Christmas Truces’, on the Western Front, after 1914. More accurately, the Western Front proved a brutal battlefield, with attritional warfare and great slaughter over four years. It left 7.5 million acres of wasteland, polluted by chemical warfare, unexploded shells and unburied dead and thousands of villages and town obliterated.

Stalemate and the use of Terror Weapons 1915-17

It was on the Western Front, that many modern weapons of mass destruction, were used for the first time.

* On the 22nd April 1915, the Germans first used poisonous gas against French and Canadian troops. They released 168,000 tonnes of chlorine gas, along a 4 mile front, killing 5,000 men and wounding another 5,000. By the end of the war all sides were using poison gas. In fact, some 30 types of poisonous gas were developed throughout the War, and some 119,000 tons of gas were used. In total, 1,200,000 soldiers on both sides were gassed, of which 91,198 died horrible deaths.

* On the 30th July 1915, the Germans first used ‘Flame Throwers‘. Their flame throwers could fire jets of flame as far as 130 feet (40 m). These were deployed against British trenches at Hooge, where the lines were just 4.5 metres. The surprise attack at 3.15am, proved terrifying to the British. However, although initially pushed back, the line was later stabilised that night by the 8th Rifle Brigade and 7th Bn KRRC. In two days of severe fighting the British lost 31 officers and 751 other ranks.

* On 15th September 1916, Britain launched the first ever Tank attack at Flers. While slow, prone to break down and used in limited numbers, tanks initially shocked the German and penetrated heavy defences.

* Tunnelling under the enemy defences was another extensively used weapon on the Western Front. At Messines Ridge, the Allies dug some 8,000 metres of tunnels. On the 7th June 1917, under a 9 mile ridge of villages, the British detonated 19 underground mines simultaneously, killing some 10,000 Germans instantly.

* The Western Front also saw the first mass use of machine guns, artillery duels and air warfare. The French 75mm cannon, was named by the Germans, as the ‘Devil Gun‘, which could fire 15 shells a minute, accurately on a target, over 4 miles away.

The Germans developed ‘Big Bertha‘, a 48-ton howitzer. It was named after the wife of its designer Gustav Krupp. It could fire a 2,050-lb shell a distance of 9.3 miles. It took a crew of 200 men six hours or more to assemble. Germany had 13 of these huge guns or “wonder weapons.” An arms race developed between all sides to deploy these weapons more destructively. Over a billion shells were fired on the Western front – the equivalent of a tonne of explosives fired for every square meter of land. Killing increased on an industrial scale. The Battle of Verdun saw combined losses of 700,000 men, the Battle of the Somme caused another million casualties and the Passchendaele offensive another 600,000 casualties. Despite successes in Italy, it was the mounting casualties along the Western Front, that forced Germany and its allies to sue for peace.

The return to mobile warfare 1918

To break the stalemate on the Western Front, Germany bouyed by reinforcements from the Russian front, launched four offensives in 1918. These offensives were code named: Michael, Georgette, Gneisenau and Blücher-Yorck). While initially successful, these Offensives were being steadily undermined by discontent at home. Germany, and Austro-Hungary were facing bankruptcy and famine. Bulgaria, a key German ally wanted peace. Civilians on the axis home front were becoming frustrated, war weary and hungry. They wanted change, peace and democracy. In January 1918, mass strikes in Berlin and elsewhere, called openly for the Kaiser’s abdication. These strikes were ruthlessly suppressed by Ludendorff, who arrested 3,000 strikers and sent them to the front. This only served to spread pessimism and revolution to German troops on the battlefield. While the German Offensives since March 1918 had captured vast territory, the land was strategically of little value and had cost Germany 785,000 dead. Advancing Germans were becoming difficult to supply with food and weapons across war torn battlefields. Many German soldiers became tired and desperate, surrendering in vast numbers. Some 386,000 demoralised German troops surrendered on the Western Front in the last three months of the war. Germany could have used its Spring Offensives as an opportunity to sue for a favourable armistice, or retreat to more fortified defences to give its army a rest. However, Germany was effectively controlled by a military dictatorship which insisted on total victory. While the Germans recovered in places and often fought stubbornly , the Allies, strengthened by American troops, and unified under the sole leadership of Marshall Foche, were developing new tactics and new weapons. Over the last 100 days, the Allies, launched a series of counter attacks all across the Western Front. To their own surprise, they pushed the Germans back, very slowly and very bloodily, to the Belgian border. While the Allies were grinding the Germans down through their superior factories, technology, manpower and command, they still lacked the logistical capacity and political will to defeat the Germans on German soil. All sides were by now becoming exhausted and reluctant to waste further lives. The Allies were planning another Offensive in 1919, when an Armistice was called on the 11th November 1918. It was thought at the time that this was just a pause in the war, but it turned out to be the end of the First World War on the Western Front. The worn out Central powers eventually sued for peace. The war on the Western Front, officially ended at 11 am, on the 11th November, 1918.

The 1914-18 War, had cost nearly 4 million Allied casualties and over 3.5 million German casualties on the Western Front alone. Nearly 750,000 Commonwealth soldiers, sailors and airmen died on the Western Front. They are buried in more than 1000 Military and 2000 civil cemeteries. More than 300,000 have no known grave and are commemorated on memorials to the missing; there are seven in Belgium and 22 in France. Some of these, like the Menin Gate and Tyne Cot at Ypres and the Thiepval Memorial on the Somme are well known and visited regularly. Others like the Indian Memorial at Neuve Chappelle are more lonely. Those they commemorate were Regulars, Territorials, volunteers and conscripts, aged from fourteen to sixty eight and ranging in rank from private soldier to lieutenant-general.

The Western Front along 250 miles and 25-30 miles wide had been reduced to a wasteland. 1,659 towns and communes had been blotted out, 2,363 others were wrecked, and 630,000 houses were destroyed or seriously damaged. So many mines were ruined, that the output of coal was reduced by a half, 21,000 factories were gutted, and the great manufacturing centres at Lille, and the Longwy district, were systematically despoiled of machinery vital to their prosperity. Deaths of civilians by artillery in the battle zone, or in the back areas by aircraft were frequent. Deaths still continue due to unexploded munitions in the Western front area. In France, around 350,000 houses were destroyed, along with 11,000 public buildings and 62,000 kilometres of railway lines. An area of about 116,000 hectares, or 460 square miles of land, in France, was declared a “Red Zone”, forever deemed uninhabitable, due to WW1 activity. The area today remains saturated with unexploded shells (including many gas shells), grenades, and rusty ammunition. Soils are heavily polluted by mercury, chlorine, arsenic, various dangerous gases, acids, and human and animal remains. The area is also littered with ammunition depots and chemical plants. Two small pieces of land near Ypres and Woevre, still remain off limits and 99% of plant life dies due to WW1 pollution. Human remains are still recovered regularly from the Western Front battlefields. About ten ww1 bodies are found around Ypres, each year. In 2009, 250 mostly Australians, were uncovered at Fromelles in France. In 2015, the remains of 125 French, British and German soldiers, some as young as 15, were found entombed in a perfectly preserved trench, on Hill 80, near Ypres. On.15th March 2021, 270 German soldiers were discovered, sealed in the buried Winterberg tunnel, near Craonne, Reims. In 1973, 400 German soldiers were found in a similar tunnel at Mont Cornillet, east of Reims, on the same Chemin des Dames battlefront. During World War I, an estimated one tonne of explosives was fired for every square metre of territory on the Western front.. As many as one in every three shells fired did not detonate. The French Département du Déminage (Department of Mine Clearance) recovers about 900 tons of unexploded munitions every year. Since 1945, approximately 630 French clearers have died handling unexploded munitions. In just the area around Ypres, 260 people have been killed and 535 have been injured by unexploded munitions since the end of the First World War. In 2013, 160 tonnes of munitions, ranging from bullets to 15-inch (38 cm) naval gun shells, were unearthed from the areas around Ypres. An annual “iron harvest” of unexploded shells, barbed wire, shrapnel, bullets and congruent trench supports are collected by Belgian and French farmers after ploughing their fields. In a normal year, the Metz Demining Centre says it collects between 45 and 50 tonnes of ordnance, and it estimates there are at least 250 to 300 tonnes still buried in the nearby rivers and rolling hills of eastern France. It is estimated that the WW1 battlefields will take another 100 years to clear.

So ended the “Great War”. The Allies had not so much won the war, but had refused to break and give in. The Germans still held much of their initial territory and marched home in good order, with their weapons. German soldiers were welcomed home as an undefeated army. This would create the myth that Germany had not lost the war, but had been undermined by revolution back home. A myth that would fuel revenge and cause the Second World War twenty years later. In truth Germany had lost the war. It was bankrupt, starving and on the verge of social collapse. It had no allies or resources to continue the war. It could not defeat America the richest nation, and France with the largest army and Britain with the world’s most powerful Navy. The Allies who were evolving new weapons and tactics and out producing Germany in every facet of war, were planning a Spring Offensive in 1919, but decided not to risk more lives needlessly. The Allies very much felt that they had won the war. Crippled by debts, the Allies forced Germany to sign the Treaty of Versailles, on 28 June 1919. Germany was made to accept full responsibility for starting the war and then repay the costs of the war to the Allies, through severe reparations which crippled the German economy. In addition, the German Rhineland was de-militarised and the Germany army restricted to only 100,000 men with no tanks, aircraft, U-Boats or modern weapons. German re-unification with Austria was outlawed to prevent this powerful threat ever re-surfacing again. German territories were given away and millions of German speaking people were to become minorities, in the newly formed nations of Poland and Czechoslovakia. These sanctions would humiliate Germany, rekindle a desire for revenge and lead to Germany overrunning Europe again in 1939.

Trench Life and Warfare

Trenches could be infested with rats, lice, snakes and frogs! Soldiers were in the front or reserve line trenches for about eight days at a time, before being relieved. Over the course of the war, soldiers could spend months, if not years, living in Trenches. The daily routine of Trench life began with the morning ‘stand-to’. An hour before dawn everyone was roused and ordered to man their positions to guard against a dawn raid by the Germans. With stand-to over, it was time for the men to have breakfast and perform ablutions.  Once complete, the NCOs would assign daily chores, before the men attended to the cleaning of rifles and equipment, filling sandbags, repairing trenches or digging latrines. Once the daily tasks had been completed the men who were off-duty would find a place to sleep. Due to the constant bombardments and the sheer effort of trying to stay alive, sleep deprivation was common. Soldiers also had to take it in turns to be on sentry duty, watching for enemy movements. Each side’s front line was constantly under observation by snipers and lookouts during daylight; movement was therefore restricted until after the dusk stand-to and night had fallen. Under the cover of darkness, troops attended to vital maintenance and resupply, with rations and water being brought to the front line, fresh units swapped places with troops moving to the rear for rest and recuperation. Trench Raiding was also carried out and construction parties formed to repair trenches and fortifications, while wiring parties were sent out to repair or renew the barbed wire in “No Man’s Land” An hour before dawn, everyone would stand-to once more.

Once complete, the NCOs would assign daily chores, before the men attended to the cleaning of rifles and equipment, filling sandbags, repairing trenches or digging latrines. Once the daily tasks had been completed the men who were off-duty would find a place to sleep. Due to the constant bombardments and the sheer effort of trying to stay alive, sleep deprivation was common. Soldiers also had to take it in turns to be on sentry duty, watching for enemy movements. Each side’s front line was constantly under observation by snipers and lookouts during daylight; movement was therefore restricted until after the dusk stand-to and night had fallen. Under the cover of darkness, troops attended to vital maintenance and resupply, with rations and water being brought to the front line, fresh units swapped places with troops moving to the rear for rest and recuperation. Trench Raiding was also carried out and construction parties formed to repair trenches and fortifications, while wiring parties were sent out to repair or renew the barbed wire in “No Man’s Land” An hour before dawn, everyone would stand-to once more.

Before an attack , a set procedure was used by a division that was moving into the front line. Once they had been informed that they were moving forward, the brigadiers and battalion commanders would be taken to the forward areas to reconnoitre the sections of the front that were to be occupied by their troops. Meanwhile, the battalion transport officers would be taken to the headquarters of the division that they were relieving to observe the methods used for drawing rations and ammunition, and the manner in which they were supplied to the troops at the front. Detachments from the divisional artillery group would move forward and were attached to the artillery batteries of the division they were relieving. Five days later, the infantry battalions that were destined for the front line sent forward their specialists from the Lewis gun teams, and the grenade officer, the machine gun officer, the four company commanders, and some of the signallers to take over the trench stores and settle into the trench routine before the battalions moved in. Overnight, the battalions would move into the line, and the artillery would take over the guns that were already in position, leaving theirs behind to be taken over by the batteries that had been relieved.

Major Battles on the Western Front

The names and dates of Britain’s WW1 battles, were decided by the House of Commons, Committee of Imperial Defence. Between 1915-1949, it produced 109 volumes of Britain’s WW1 war effort which became the British Official History of the Great War. There were many contributors to the WW1 history, the chief one being the Committee Director, Brigadier general, Sir James Edward Edmonds, (1861-1956), a military historian, of considerable intellect, fluent in many European and Asian languages. While criticised for being misleading and bias towards Britain’s WW1 Generals, Edmond’s works were of substantial historical, military and literary value.

The Battle of Mons – 23 August 1914

The Battle of Mons was the first major action of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in the First World War. At Mons, the British Army which numbered 80,000, attempted to hold the line of the Mons–Condé Canal against the advancing German 1st Army. They were outnumbered by the Germans 3:1. Although the British fought well and inflicted disproportionate casualties on the numerically superior Germans, they were eventually forced to retreat. This was due both to the greater strength of the Germans and the sudden retreat of the French Fifth Army, which exposed the British right flank. Though initially planned as a simple tactical withdrawal and executed in good order, the British retreat from Mons lasted for two weeks and covered over 250 miles (400km). The British were closely pursued by the Germans throughout and fought several rearguard actions, including the Battle of Le Cateau on 26 August, the Étreux rearguard action on 27 August and the Action at Néry on 1 September. It took the BEF to the outskirts of Paris before it counter-attacked in concert with the French, at the Battle of the Marne. Both sides had success at the Battle of Mons: the British had been outnumbered by about 3:1 but managed to withstand the German 1st Army for 48 hours, inflict more casualties on the Germans and then retire in good order. At Mons the British suffered 1,638 Casualties. The Germans lost between 2,500 – 5000 men

By 22 September 1914, following the First Battle of the Marne (6–12 September 1914) and the First Battle of the Aisne (12–21 September 1914), the French and German armies began fighting a series of battles side-stepping one another through northern France in an attempt to outflank the other. These outflanking manoeuvres would take them in a north-westerly direction from the Aisne region towards the French coast. This period of fighting became known as “The Race to the Sea”.

The Battle of Loos – 25 September – 8 October 1915

The Battle of Loos was the biggest British attack of 1915, the first time that the British used poison gas and the first mass engagement of New Army units. The French and British tried to break through the German defences in Artois and Champagne and restore a war of movement. In many places British artillery had failed to cut the German wire in advance of the attack. Advancing over open fields, within range of German machine guns and artillery, British losses were devastating. Twelve attacking battalions suffered 8,000 casualties out of 10,000 men in four hours. The British were able to break through the weaker German defences and capture the town of Loos-en-Gohelle, mainly due to numerical superiority. Supply and communications problems, combined with the late arrival of reserves, meant that the breakthrough could not be exploited. British casualties at Loos were nearly 60,000 about twice as high as German losses. The Loos Memorial commemorates over 20,000 soldiers of Britain and the Commonwealth who fell in the battle and have no known grave.

The Battles for Ypres – 1914-1918:

Ypres was one of the few parts of Belgium not occupied by the Germans. It became a symbol of Belgium resistance. It was also a major strategic position during the First World War because it stood in the way of Germany‘s planned sweep across the rest of Belgium and into France from the north (the Schlieffen Plan). The neutrality of Belgium was guaranteed by Britain; Germany‘s invasion of Belgium brought the British Empire into the war. The German army surrounded the city on three sides, bombarding it throughout much of the war. To counterattack, British, French, and allied forces made costly advances from the Ypres Salient into the German lines on the surrounding hills. Ypres was one of the sites that hosted an unofficial Christmas Truce in 1914 between German and British soldiers. Men from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, India South Africa and other commonwealth countries all fought at Ypres, alongside men from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales to preserve Ypres from capture.

The land surrounding Ypres to the north is flat and canals and rivers link it to the coast. Ypres was the major centre in this part of Flanders. Control of the town gave control of the surrounding countryside and all the major roads converged on the town. To the south of the town the land rises to about 500 feet (the Mesen Ridge) which would give a significant height advantage to whichever side controlled this ridge of high land.

First Battle of Ypres (19 October to 22 November 1914), the Allies captured the town from the Germans. The first days of November directly affected the town. Each day Ypres was shelled and civilian casualties were high. This tactic set the scene for what Ypres was to suffer for several more years. By the winter, the Germans had not taken Ypres and heavy rain meant that any movement was impossible as the roads turned to mud. The first battle at Ypres limped to a halt.

Second Battle of Ypres (22 April 1915– 25 May 1915)

The battle consisted of six engagements:

- Battle of Gravenstafel: Thursday 22 April – Friday 23 April 1915

- Battle of St. Julien: Saturday 24 April – 4 May

- Battle of Frezenberg: 8–13 May

- Battle of Bellewaarde: 24–25 May

- Battle of Hooge: 30–31 July 1915 (first German use of flamethrowers)

- Second Attack on Bellewaarde 25 September

Once the weather had settled, the Germans prepared for a new attack. They used deadly chlorine gas against defending French troops. Having never experienced this before, terrified French soldiers fled. The Gas had worked as it had got them to leave their positions. The situation was saved by Canadian troops who used handkerchiefs soaked in urine as gas masks and launched a counter-attack on the Germans. It was successful and the Germans lost the gains they had made.

Also in April, the French exploded mines under the German position held at Hill 60 – in fact, a mound created from the rubbish cleared when a railway cutting was made. Whoever controlled Hill 60 had a perfect view of what was going into Ypres and what was leaving. Hence its strategic value. Though successful, the area was reduced to a muddy bog. The British took Hill 60, but were pushed out by another successful poison gas attack by the Germans. The Germans were only pushed out of Hill 60 in 1918.

To the south of Ypres lies Mesen. The hills around Mesen had been controlled by the Germans since 1914, and to give the Allies a morale boost, the Allied High Command ordered an attack on Mesen Ridge. The Allies had spent time digging tunnels underneath the Ridge which were packed with explosives. On June 7th,1917, nineteen of the mines were detonated. The noise of the explosions was heard in London. Tens thousand Germans were killed instantly. The stunned German troops on the Ridge were easily taken by the Australian and New Zealand troops that attack the Ridge after the explosions.

Third Battle of Ypres (31 July to 6 November 1917, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele)

To the north east of Ypres, plans went less well for the Allies. British and Commonwealth forces were pursuing an ambitious goal: to break through the German lines to reach the Belgian coast and neutralise the U-boats that threatened British supply lines. However, the campaign coincided with the wettest summer for a century, turning the battlefield into a sea of mud. In October 1917 the area was drenched with rain – for a month. Conditions for the troops were appalling. Trench foot was common on both sides.

The last shell fell on Ypres on the 14th of October 1918. In the area around Ypres – including Hill 60, Passchendaele, Lys, Sanctuary Wood etc. – over 1,700,000 soldiers on both sides were killed or wounded and an uncounted number of civilians.

The Menin Gate Memorial at Ypres was unveiled on 24 July 1927. Designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, its large Hall of Memory contains names on stone panels of 54,395 Commonwealth soldiers who died in the Salient, but whose bodies have never been identified or found. On completion of the memorial, it was discovered to be too small to contain all the names as originally planned. An arbitrary cut-off point of 15 August 1917 was chosen and the names of 34,984 UK missing after this date were inscribed on the Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing instead. The Menin Gate Memorial does not list the names of the missing of New Zealand and Newfoundland soldiers, who are instead honoured on separate memorials. In the 1920’s, British veterans set up the ‘Ypres League’ and made the city the symbol of all that they believed Britain was fighting for and gave it a holy aura in their minds. Ypres became a pilgrimage destination for Britons to imagine and share the sufferings of their men and gain a spiritual benefit. In the 100th anniversary period more attempts are being made to preserve the First World War heritage in and around Ypres. Passchendaele and the extra height that the area would give the victors started on October 12th. By November 6th, the area had been captured for the Allies at terrible loss, for both sides. If one battle summarises the pain and futility of war it was Passchendaele. It is remembered not only for the rain that fell, the mud that weighed down the living and swallowed the dead, but also for the courage and bravery of the men who fought here. In just three and half months of terrible fighting, some 500,000 men became casualties for about 900 metres of land. More VCs were won on the 31st July 1917, the first day of the Battle of Passchendaele than on any other single day of battle in the First World War, and 61 VCs were awarded during the campaign as a whole. All the territory gained at Passchendaele was lost again in just three days, during the German spring offensive of 1918.

The Battle of the Somme (1 July and 18 November 1916)

To relieve pressure on the French at Verdun, and to prevent the Germans transferring troops to the Italian or Russian fronts, a large-scale Allied offensive, was launched on 1 July 1916, against the German Front Line, along the Somme River. The British Army attacked north of the river, the French Army attacked south of the river. The battle is usually regarded in three phases. The first, from the 1st-17th July, when a footing was gained on the hill crest between Deville Wood and Bazentine-le-Petit, the second, from the 17th July to the first week of September, when violent counter attacks were beaten back, and the British position on the highland was made good, and the third phase, from September, to November, when an advance was made down the northern and eastern slopes to consoldiate the flanks. The battles lasted for a gruelling four months with many thousands of casualties on both sides of the wire. The first day on the Somme (1st July) saw a serious defeat for the German Second Army, which was forced out of its first position by the French Sixth Army, from Foucaucourt-en-Santerre, south of the Somme to Maricourt, on the north bank and by the Fourth Army from Maricourt to the vicinity of the Albert–Bapaume road. The British attack along the front, between the Albert–Bapaume road and Gommecourt, fared much worse. While the British fired over a million shells at the German lines a week before the attack, some 35% of munitions were defective and of the wrong type. Many shells failed to explode. They did not cut the german wire or penetrate the deep German bunkers under ground. Recently found German archives also reveal that the Germans had learnt from captured prisoners and listening posts, when, and where the attack would start, and in many cases, which troops would confront them on the opening day. When the whistles blew at 7.30am on the 1st July 1916, 100,000 British troops emerged from their trenches and walked slowly towards the German line. They confidently believed that nothing could have survived the previous week’s bombardment. Counting from the right, the 30th, 18th and 7th Divisons were successful at Montauban and Mametz, a distance of about 5 miles, and the 21st, 34th and 8th, were partially successful at Fricourt, La Boisselle, and Ovillers. On the left, the 32nd and 36th Divisions, failed near Thiepval, the 29th and 4th, near Beaumont Hammel, the 31st at Serre, and the 56th and 46th near Gommercourt.

The cause of the failure was that the Germans were expecting the attack, and had prepared their defences and brought up extra guns. They had also surveyed and defended the battlefield for the last two years. Their artillery and machine guns covered all the battlefield and were trained to follow moving targets, within range. The British troops at the Somme, facing them, comprised a mixture of the remains of the pre-war Regular army, the Territorial Force; and mostly Kitchener’s Army, a force of volunteer recruits including many Pals’ Battalions, recruited from the same places and occupations. The “Pals”, were probably Britain’s fittest, brightest and most enthusiastic soldiers, but they were very inexperienced and tactically naive. Britain’s ‘Pal’ battalions which had taken two years to train, were decimated in the first 10 minutes of battle. Many troops failed to even reach their own front line, let alone the Germans and where there were successes, they were obtained at enormous cost. British losses on the first day, were the worst in the history of the British army, with 57,470 British casualties,19,240 of whom were killed.

The Somme battle is notable for the importance of air power and the first use of the tank. At the end of the battle, British and French forces had penetrated 10 km (6 miles) into German-occupied territory, taking more ground than in any of their offensives since the Battle of the Marne in 1914. The Anglo-French armies failed to capture Péronne and halted 5 km (3 miles) from Bapaume, where the German armies maintained their positions over the winter. British attacks in the Ancre valley resumed in January 1917 and forced the Germans into local withdrawals to reserve lines in February, before the scheduled retirement to he Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg Line) began in March. The Battle of the Somme was one of the costliest battles of World War I. The original Allied estimate of casualties on the Somme, made at the Chantilly Conference on 15 November 1916, was 485,000 British and French casualties and 630,000 German. While Allied casualties were appalling, a school of thought has emerged that the battle seriously drained German resources impeding their chance of final victory. The destruction of German units in battle was made worse by lack of rest. British and French aircraft and long-range guns reached well behind the front-line, where trench-digging and other work meant that troops returned to the line exhausted. As well as capturing 38,000 prisoners, the British army had gained much needed battle experience and the confidence of driving the Germans from strong, fortified positions and holding these gains, against frequent counter attacks.

The Somme Battle: First phase: 1st –17th July 1916

First day on the Somme, 1 July 1916 – Main article: First day on the Somme

Battle of Albert, 1–13 July 1916 – Main article: Battle of Albert (1916)

Battle of Bazentin Ridge, 14–17 July 1916 – Main article: Battle of Bazentin Ridge

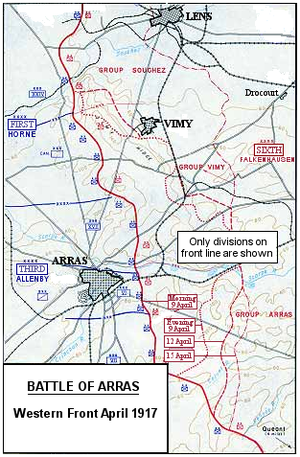

THE BATTLE OF ARRAS (9 April to 16 May 1917)

First Battle of the Scarpe (9th –14th April 1917) Main article: Battle of Vimy Ridge

British troops attacked German defences on high ground, near the French city of Arras on the 9th April 1917. The British achieved the longest advance since trench warfare had begun, surpassing the record set by the French Sixth Army on 1 July 1916.The preliminary bombardment of Vimy Ridge started on 20 March; and the bombardment of the rest of the sector on 4 April. Limited to a front of only 24 miles (39 km), the bombardment used 2,689,000 shells, over a million more than had been used on theSomme. The assault was preceded by a hurricane bombardment lasting five minutes, following a relatively quiet night. When the time came, it was snowing heavily; Allied troops advancing across no man’s land were hindered by large drifts. It was still dark and visibility on the battlefield was very poor. The British advance slowed in the next few days and the German defence recovered. The battle became a costly stalemate for both sides and by the end of the battle the British Third and First armies had suffered about 160,000 casualties and the German 6th Army 125,000 casualties.

The Second Battle of the Scarpe (23th –24th April 1917)

This included a series of battles – The Battle of Arleux (28–29 April 1917); the Third Battle of the Scarpe (3–4 May 1917) (See also: Capture of Oppy Wood); the First attack on Bullecourt (10–11 April 1917); the German attack on Lagnicourt (15 April 1917) and the Battle of Bullecourt (3–17 May 1917). By the standards of the Western front, the gains of the first two days of the Arras battle, were spectacular. A great deal of ground was gained for relatively few casualties and a number of strategically significant points were captured, notably Vimy Ridge. Additionally, the offensive succeeded in drawing German troops away from the French offensive in the Aisne sector. In many respects, the battle might be deemed a victory for the British and their allies, but these gains were offset by high casualties and the ultimate failure of the French offensive at the Aisne. By the end of the offensive, the British had suffered 158,660 casualties and gained little ground since the first day. German losses are more difficult to determine, but at least 79,418 casualties and possibly as many as 130,000. Siegfried Sassoon makes reference to the battle in the poem The General. The Anglo-Welsh lyric poet Edward Thomas was killed by a shell on 9 April 1917, during the first day of the Easter Offensive. Thomas’s war diary gives a vivid and poignant picture of life on the Western front in the months leading up to the battle. The composer Ernest John Moeran was wounded during the attack on Bullecourt on 3 May 1917.

Battle of Cambrai (20th November – 7th December 1917)

The Battle of Cambrai, fought in November/December 1917, proved to be a significant event in World War One. Cambrai was the first battle in which tanks were used en masse. In fact, Cambrai saw a mixture of tanks being used, heavy artillery and air power. Mobility, lacking for the previous three years in World War One, suddenly found a place on the battlefield – though it was not to last for the duration of the battle. While the battle of Passchendaele was being fought, Douglas Haig approved a plan to take on the Germans by sweeping round the back of Cambrai and encircling the town. The attack would use a combination of old and new – cavalry, air power, artillery and tanks that would be supported by infantry. Cambrai was an important town as it contained a strategic rail head. The Cambrai battle started at 06.20 on November 20th 1917. The Germans were surprised by an intense artillery attack directly on the Hindenburg Line. 350 British tanks advanced across the ground supported by infantry – both were assisted by an artillery rolling barrage that gave them cover from a German counter-attack. The bulk of the initial attack went well. The 62nd Division (West Riding) covered more than five miles in this attack from their starting point. Compared to the gains made at battles like the Somme and Verdun, such a distance was astonishing. However, not everything had gone to plan. The 2nd Cavalry Division had a problem crossing the vital St.Quentin Canal when a tank went over its main bridge and broke its back – the same bridge that the cavalry were supposed to use to advance to Cambrai! Elsewhere, British units also got bogged down in their attack. By November 30th, the German were ready to counter-attack and defend Cambrai. Many British army units had got themselves isolated and their command structure broke down in places. The German counter-attack was so effective that on December 3rd, Haig gave the order for the British units still near to Cambrai to withdraw “with the least possible delay from the Bourlon Hill-Macoing salient to a more retired and shorter line.” The failure to build on the initial success of the attack was blamed on middle-ranking commanders – some of whom were sacked. The initial phase of the battle did show that mobility was possible in the war, but that to sustain it, a decent command structure was needed so that impetus gained in one area of the attack was aided by gains elsewhere in the advance. British casualties were over 44,000 men during the battle, while the Germans lost about 45,000 men.