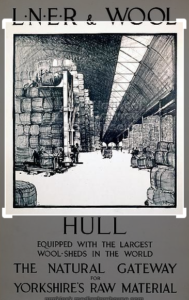

Hull has historically enjoyed successful trade links with most of the ports of Northern Europe, from Antwerp in the west, to St. Petersburg in the east, Le Havre in the south and to Trondheim in the north. Between 1836-1914, 2.2 million people, mostly from Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, Russia and Sweden, passed through Hull, on their way, to America, Canada, South Africa and Australia. Some of these people stayed in the City, adding to its commerce and culture. Hull was at the peak of its prosperity in 1914. Hull was Britain’s Second biggest Port and the Worlds largest seed crushing center. Over half of Britain’s,1.25 million tons of oil seeds, came to Hull to be crushed, refined into oil and made into feed cakes for live stock. Hull was the first town to adopt hydraulic power for public use, laying hydraulic power mains in a line following the Old harbour and River Hull, from the Pier to Sculcoates Bridge. This powered Britain’s Seed Crushing industry and Hull was the first to import cotton seeds from Egypt in 1900, to make into oil for fish fryers. It also spawned many successful Hull industries, along the River Hull, which included tool making, seed crushing engineering, oil extraction, high temperature heating and oil milling. The First World War, however, would change and damage Hull’s shipping and trade for decades.

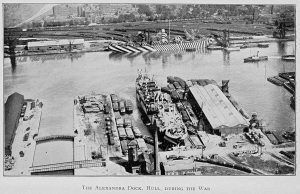

Hull’s foreign trade declined from 4.7 million tons in 1913, to just 1.6 million tons, in 1917. The tonnage of shipping entering Hull ports in 1914 was a record of 6.6 million, a figure not matched until 1923. Hull’s coal exports in 1914, were never again equalled, and the imports of wheat which reached a peak in 1912, did not reach the same level until 1931. The King George Dock had been opened in June 1914 to cater for this expanding trade. It was the largest and deepest of Hull’s docks, designed to compete with the Great Central Docks of Immingham. Before the war, two thirds of Hull’s trade came from Russia, Scandinavia, Denmark and Holland. However, 11.6% of this trade which came from Germany, ended immediately when war began. The wool trade with Australia, which had been built up before the war, collapsed entirely when war began. Hull used its long standing trading connections with neural countries like, Sweden, Norway and Holland, to maintain dairy and timber supplies during the war. However this changed in 1917, when Germany declared unrestricted sea war on all neural merchant shipping.

Hull’s foreign trade declined from 4.7 million tons in 1913, to just 1.6 million tons, in 1917. The tonnage of shipping entering Hull ports in 1914 was a record of 6.6 million, a figure not matched until 1923. Hull’s coal exports in 1914, were never again equalled, and the imports of wheat which reached a peak in 1912, did not reach the same level until 1931. The King George Dock had been opened in June 1914 to cater for this expanding trade. It was the largest and deepest of Hull’s docks, designed to compete with the Great Central Docks of Immingham. Before the war, two thirds of Hull’s trade came from Russia, Scandinavia, Denmark and Holland. However, 11.6% of this trade which came from Germany, ended immediately when war began. The wool trade with Australia, which had been built up before the war, collapsed entirely when war began. Hull used its long standing trading connections with neural countries like, Sweden, Norway and Holland, to maintain dairy and timber supplies during the war. However this changed in 1917, when Germany declared unrestricted sea war on all neural merchant shipping.

Many Hull ships were arrested or stranded in foreign ports, when war began. They were unable to return to Hull, through the German naval patrols. For example, only 40 ships arrived in Hull from Russia in 1917, compared to 757 in 1913. The number of trading ships reduced from, approximately, seven hundred to no more than forty.

Hull had monopolized ship passenger services before the war and the port played a major role in the emigration of Northern European settlers to the New World. Over 2 million emigrants passed through Hull, before travelling on to Liverpool and then North America. Many of these migrants stopped and made Hull their home, increasing the City’s population, Status, and unemployment. Many of these passenger ships, such as those owned by the Wilson Line in Hull, were sunk during the First World war, with the Company being sold in 1916.

Hull had also developed several successful fishing fleets before the war, but many of these new and technologically advanced ships were requisitioned by the Admiralty. Hull’s well-developed fishing industry became almost impossible during the war, as it was dangerous even to sail in the North Sea. This meant all Hull’s fish and chips shops closed during the war.

The Government also diverted coal and cargo away from Hull, particularly after the bombing of Scarborough in December 1914 and the Zeppelin raids over Hull, in June and August 1915. In response, Hull’s Earle shipyards continued to build ships in Hull during the war, but this was limited due to the scarcity of raw materials and manpower, required elsewhere for the war effort. Hull created new munition factories in 1916 and successfully supplied five Government contracts, during the war. With rising food shortages, the British Oil and Cake Mill, in Hull opened a new Margarine factory in 1917. This produced 200 tons of Margarine a week (Britain consumed 5,000 tons a week) It was hoped that Hull would become a major Margarine producer and Cooking fat exporter. Sadly, this never materialised. The City’s Oil producing industries were gradually overtaken by the Lever Brothers soap production in Liverpool. Therefore, while the First World War provided Hull with some opportunities, it mostly it had a negative impact on the City’s trade and industry. Once Britain’s third largest (and cheapest ) port, Hull represented only 6% of Britain’s economic output, by the end of the war.

Hull Industries: While Hull compensated with some increased trade with neutral countries, like Sweden and Holland, this too reduced in February 1917, when Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare on any shipping helping the Allies. Losses to shipowners were also severe. The Wilson Line, Hull’s largest merchant shipping company, had lost 15 of its 79 ships by 1916, and by the end, over 40 of its 84 vessels and some 300 crew members. The tonnage of shipping registered in Hull Ports fell from 230,000 ton in 1913 to 182,000 by 1917. Therefore, from probably it’s most prosperous period in 1914, Hull declined through the war, and took decades to recover. With so many Hull people dependent on the docks for work, the War had an immediate impact on livelihoods and acted as an incentive for young men to enlist.

Much of Hull’s economy was turned towards winning the war. It’s existing Industries and trades were mixed and varied. Its’ shipyards built modern minesweepers, anti submarine patrol boats and Tugs. It’s well established factories at Fenners, Needler’s, Rank Hovis and Reckitt’s, were expanded and adapted towards the war effort. Its Passenger fleets, like the Ellerman Wilson Shipping Line, supplied the British Government with 92 vessels to use as troop ships, munitions carriers, and converted armed merchant cruisers to strengthen the Royal Navy. It lost three of its largest and most prestigious ships to enemy action (Aaro and Calypso sunk; Eskimo captured) in a three-week period in the summer of 1916, and only 67 short sea vessels were left when the Wilson family sold the company to John Ellerman in 1916. John Ellerman, then lost 103 ocean vessels during the war, with a total cargo capacity of 600,000 to 750,000 tons. These included the liner City of Athens mined off Cape Town in August 1917. The City of Winchester (1914) was captured by the German cruiser Königsberg, while homeward bound from India with a very valuable cargo of produce. The City of Exeter, a fine passenger liner belonging to the Ellerman fleets was mined in the Indian Ocean, about 400 miles from Bombay. The Ellerman Wilson Roll of Honour in Hull commemorates hundreds of former employees lost in all services during the war. Hull fishing fleets, such at Hellyer Brothers and Red box were similarly used for war work. They were particularly useful for minesweeping and keeping supply lines free of hazards.

Smith & Nephews’, began as a local pharmacy in 1856. It expanded to become a medical supplies company, based at Neptune Street, Hull. During the First World War, It grew from 50 to 1,200 employees, and supplied field dressings and surgical equipment for the Allies, throughout the war. One particular order, for the French Government, in October 1914, was worth £350,000 (£43 million in 2022 prices), and was delivered in just 5 months. On the Saturday after the fall of Antwerp in October 1914 (where the Belgian army lost the whole of its medical supplies), Horatio Nelson Smith (the Nephew of founder Thomas James Smith) met Commander, Vigneron, of the Belgian Army Medical Service. Supplies were needed for the following Monday, and the entire team in Hull worked without a break throughout the weekend. Ten tonnes of dressings were loaded onto special trucks at 9.30am and were in the hands of the Belgian authorities by 8.00pm that night. Throughout the war, the company supplied dressings not only to the armies of Britain, France, Belgium and Serbia, but, on their entry, also to the American Army and the American Red Cross. Every British soldier carried two field dressings, many manufactured by Hull’s Smith & Nephew and this no doubt helped to save many lives.

Joseph Rank Ltd, of Clarence Street, played a crucial role in flour production. During the war years, the company employed 3,000 workers, many of them women who took on production jobs while men were away fighting the war. Starvation was a real threat to the people of Great Britain and Joseph Rank himself was asked to join the Wheat Control Board due to National food shortages. Frustrated by the government’s inability to warehouse large quantities of wheat as distribution became chaotic as many ships carrying supplies were sunk, he relied much on his own resources and initiative to buy and store quantities of wheat and to increase the production capacity of his London mill.

Reckitt’s expanded at the outbreak of the war by buying two German companies based in England – Rawlin’s & Son and the Global Metal Polish Company. They employed 4,761 in 1915 which rose 5,609 in 1917. By the Armistice 1,100 Reckitt’s employees were serving in the armed forces and 153 had lost their lives. Being Quakers, Reckitt’s factories, produced non combative war goods, such as cleaning materials, gas masks, and petrol cans. Reckitt’s social club hall was used as a Voluntary Aid Detachment hospital. The hospital was staffed by members of the Reckitt Nursing Division, with James Reckitt appointed as acting commandant. Reckitt’s supported the joining up of married men by making up the difference between their former wages and army pay. After the war, Reckitt’s erected two Memorial tablets and an impressive war memorial in Hull. It also published photographs of many employees serving in ww1 in the staff magazine. The Reckitt family have contributed around £160m – in today’s money – to Hull’s community since the company was founded. This includes building houses in Garden Village, the James Reckitt Library, buying the site of the Ferens Art gallery, contributing to local hospitals, universities and gifting the land which is now the East Hull park.

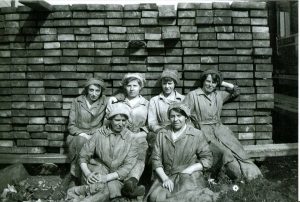

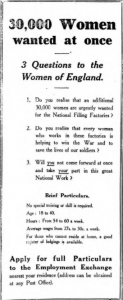

Rose, Downs and Thompsons, of Hull, was established in 1777, making cannons for the Napoleonic War. It built Britain’s first, ferro-concrete factory, using its own workforce and opened their “Old Foundry”, at Cannon Street, on 13th June, 1901. It also built the worlds’ first ferro-concrete bridge on Cleveland Street, for £758, on 13th the January 1904. This bridge linked the “Groves” district with Hull’s Stoneferry and Wilmington, greatly improving Hull’s industrial capacity and efficiency. Before the war, Rose Downs and Thompson patented and manufactured world leading, seed crushing and exported machinery across the world. It converted to making munitions in July 1915, in response to Britain’s “Shell Crisis of 1915” and in particular the shortage of high explosive shells. It produced 1,600 High Explosive shells a week and other munitions equipment, rapidly expanding its workforce throughout the war. For example, in July 1914, the firm employed 276 people, including just 3 women. By October 1918, it employed 938 workers, including 359 women (13 under 18 years of age and 341 between 18 and 51 years old). Another 212 employees were released for war service. Its Company Director, Charles Downs, a former Captain in the East Riding, Royal Garrison Artillery, and winner of the Kings (Artillery) Prize in 1908, helped to co-ordinate Hull’s munition production during the war. This was no easy task. Investigative trips to munition factories in Leicester and Rotherham in 1915, found that there were at least 17 stages to the shell making process. Each shell taking over 5 hours of labour and costing 24 shillings to make. The shell making process, included machining copper shell cases, varnishing, polishing, stamping, tapping, and screwing nose caps to the shell. Each stage of the process had to be timed and priced. It also required skilled labour, which was in short supply and sharing lathes, winches and other engineering equipment, required for trawler repairs and other competing war industries. Despite these early difficulties, Charles Downs, established the Hull & District Munitions of War Committee, on the 4th July 1915. The Hull Munitions Committee borrowed £25,000 from the Government, to convert eight Hull factories for shell production. It created an assembly line of shell production, which allowed semi skilled workers to mass produce shells. This encouraged more women into the workforce and by the end of the war Hull employed over 3,000 female “Munitionettes”. Charles Downs steered Hull firms to successfully deliver four Government Shell Contracts, during the war. On 18th February 1917, Rose Downs and Thompsons invented a new, shell making, machine, built in 13 days and 9 hours. This produced the first bomb on the 18th February 1917 and enabled Hull to produce 8,000, 4.5 inch, High Explosive Shells, per week. The Company used the Hull & Barnsley Railway line and nearby Cannon Street Goods station, to ferry munitions efficiently out of Hull.

The eight, Hull firms, which engineered shells, were the Hellyer Brothers, Trawler Owners, (2,000 shells a week); Rose, Downs and Thompson (1,600 shells); R Sizer Limited, of Cornwall Street, Wilmington (1,350 shells); CD Holmes & Co (1,000 shells); J Cherry and Sons (650 Shells); Earles Ship Building and Engineering Company (500 shells); Amos Smith Limited (600 Shells) and the St Andrews Dock Munition Committee (300 shells per week). They experimented with different types of shells, including the Canadian Mark V to Mark VII versions. Eventually, Hull specialised in producing, the fast firing, 4.5 inch, Mark V to Mark IX, High Explosive, shell, made of iron and semi steel. They collectively made 5,000 shells a week, in February 1916, increasing to 7,000 shells a week, by June 1916 and 8,000 shells a week in October 1917. By the end of the war Hull had produced 916,771 shells. (the last Hull made shell case, was given to Charles Downs, which he kept on his office table (Hull Times 21/01/1928). Hull stored manufactured shells at the Hull & Barnsley “Albion” Warehouses, on Madeley Street and distributed them from the Dairycoates Railway Depot, on Hessle Road. Shell production was often interrupted by Zeppelin raid buzzers. There were also shortages of skilled labour and materials, wage rises and rationing and competition for equipment between rival firms and businesses, which affected shell production. The Munitions Committee, for example, reported a particular bad week, on 10th July 1917, when only 5,758 shells were made.

Hull aware of its engineering capacity, rejected contracts for manufacturing Howitzers, machine guns and flying machines (13/07/1915). Hull also gave the making of 18 pounder shells to other firms, outside Hull. In addition to shell production, Robinsons, of Lockwood Street, Hull and Messrs, King & Co-Raine, of Cleveland Street, Hull, made portions of mines and submarine equipment (15/05/1917). Hull’s National Radiator Company (now Ideal standard), on Alliance Avenue, designed the 4.5 inch, cast iron, chemical shell and produced an incredible 25,000 gas shells a week (08/05/1917). In 1917, Rose Down and Thompsons started to make “Constantinesco” Fire Control sets for the Royal Flying Corps. These were fine precision control gears, that synchronised machine guns and propeller blades, allowed bullets to be fired forward, through propellers. Rose Downs and Thompson, built special premises on Reform Street, to make this essential aeroplane equipment. Starting from scratch, it produced 1,760 fire control sets, for the war effort. Messrs G Clark & Sons, of Waterhouse Lane, also made 30,000 bomb fuses a week and Rose Downs and Thompson also produced these (14/05/1918).

Only 15% of those employed on Hull’s munitions work were men of military age. The majority were boys under 18, older men and women. Female munitions workers were given a wage increase of 2/6 per week, as Fish Dock workers were being offered better terms (28/11/1916) and were paid 32 shillings a week for 53 hours work (28/02/1918). They were also provided with extra rations. Skilled munition workers were paid 41 shillings a week (02/05/1918). Shell making was a profitable business. Rose Downs and Thompson company’s weekly wage bill was approximately £870, in 1916, but the Government paid 42 shillings per shell, providing revenue of £3,200, before overheads. However, while there were profits, the Munition firms involved were very much motivated by patriotism and winning the war.

In all, Hull produced nearly a million high explosive shells and numerous gas shells for the war effort. This enabled annual national shell production to grow from 500,000 in 1914 to 76 million in 1917. By 1918, the Ministry of Munitions had a staff of 65,000 people, employing some 3 million workers, in over 20,000 factories, many of which were women. Shell production was a good business and Hull was very good at it. When the Hull & District Munitions of War Committee dissolved on 29/04/1919, it reported that Hull was the first City in the UK to repay its’ £25,000 Government War Loan, including an added £125 Interest and scored 100% efficiency marks for all its four Government Contracts. Charles Downs was given a gold watch for his efforts, as was G F Robinson of the War Saving Association, which raised £138,440 (£8.3 million in todays money). The Committee minutes state that by the end, Charles Downs had created a “Happy Band of Bothers, that had not always been the case”. He soon retired on ill health, no doubt worn down by his war work.

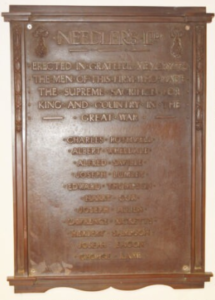

Needlers Confectionary was founded in 1886, by 18 year old Frederick Needler when he bought a small confectionery business near Paragon Station. Frederick Needler. The business proved successful and expanded several times before opening a factory at Bournemouth Street, Hull in 1906. Needlers developed a reputation for treating their employees well. From the beginning they provided staff with extensive profit sharing schemes, sick pay and pensions. Their product range included 576 lines, including 74 in chocolate. During the war, Needlers employed 1,700 workers, mostly women, to make Confectionaries and ‘Military Mints’ for soldiers at the front. Needler’s Turnover, which was £95,000 in 1913/14, peaked at £664,000 in 1920, representing some 650 tons of chocolate and 1500 tons of sweets. Needlers erected a bronze plaque to remember eleven employees killed in the war.

Many local businesses were badly affected by the loss of manpower. Some used women or injured ex-servicemen in place of the men they had lost, while others had to reduce their opening hours because of staff shortages. Women were paid only half the wage of equivalent male workers. Irish labourers got 50/- per week for helping with the harvest. The ‘Women on the Land’ Committee reported that women between 18 and 40 received 15/- per week during their 3 weeks training, then 18/- per week once trained, plus a free uniform.

By the end of the war, there were 115 major factories in Hull. Of these, 25 were involved in seed crushing and oil cake manufacture, eight in oil extracting and refining, 11 in paint and colour making, three in the manufacture of soap and two in the production of margarine. Grain warehousing was carried out in 10 factories and there were six flour mills. The fishing industry accounted for three premises for cod liver oil extraction and two factories produced fish manure. There were 13 saw mills, four ship yards and six marine and mill engineering works. Other large factories were engaged in the manufacture of starch, blue and black lead (6); tar distilling (2); the making of tin cannisters and paint drums (4); tanning and leather production (3); canvas and sack making (1); and sweets and confectionaries (1). In addition to these larger factories, a total of 1,169 workshops were registered with the City Council. The trades with the largest number of workshops were bakers (83), boot repairers (77), cabinet makers (24), coopers (39), cycle repairers (49), dressmakers (118), fish curers (62), tinsmiths (20) and watch and clock makers (27). The largest number of employees in these workshops was in the fish curing trade (407 men and 535 women), with dressmaking second (10 men and 849 women) and tailoring (271 men and 326 women) coming third. Approximately, 700 men and women were employed as outworkers, the vast majority of people being engaged in bespoke tailoring and the making of fish nets. The above details reflect the many facets of life in Hull, suits and dresses made to measure, leather boots and shoes which could be repaired, craftsman-made furniture etc. The number of bicycle repairers also indicated the large number of cycles used in the city, and it was said that only Coventry could match Hull for its number of cyclists.

Life on the home front was hard and the work often dirty and low paid. By 1919, there were at least 30 premises in Hull involved in ‘dirty’ processes, such as tripe boiling (6), cod liver boiling (5), gut scraping (3), fish manure production (3), tanning (3), fat and candle melting (2), soap boiling (2), bone boiling (2) horse slaughtering (1), hide preparation (1), cod liver oil extraction for medicinal purposes (1), and ammonia producing works (1).

The widespread use of coal for industrial power and also heating the home caused considerable smoke pollution. Public health and safety was in its infancy and there many unrecorded industrial accidents. There was also a limited welfare state, to support those unemployed or affected by the war. All this made life and work on the ‘Home Front’ particularly tough, especially for women and girls who were essential to maintain war production.

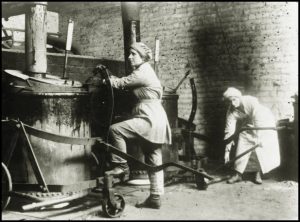

Hull’s contribution during the First World War was remarkable. Probably the complete story of Hull’s contribution in the Great War will never be known, so extensive and so diverse were the ways in which its thousands of workers toiled. While it is possible to measure actual industrial output, such as shells and other munitions, it is more difficult to assess the value of all the repairs and alterations made to hundreds of ships used by the Navy, the actual construction of war ships, how Hull’s oil, paint and colour trades helped, the manufacture of food stuffs and the contributions of all the many small trades and services carried out during the war. While Hull’s economic output undoubtedly increased during the war and assisted the nation to victory, there was little to show for the huge expenditure of labour, wages and material. Most of the unused munitions after the war were destroyed and surplus equipment became scrap. The increased production was remarkable considering the youngest and strongest of workers were away overseas. Retired men, women and girls volunteered for duties, often shortening their lives by long hours of work and increased worries and duties. (Below. Photo of three Hull Munition workers)

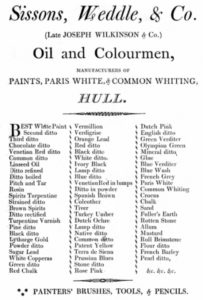

A female worker preparing paint casks in the works of Sissons and Co. Ltd., Bankside, Hull, November 1918.