WW1 – War Pensions & Grants

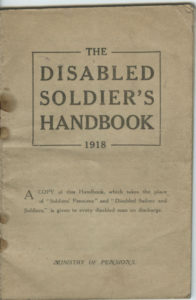

Governments were slow to respond to the needs of the wounded and their families. It was not until February 1917, that Britain established the Ministry of War Pensions. It should be noted that the Ministry of Pensions was set up primarily to reduce the rising costs of war pensions, rather than spend more money to help the victims. This shaped the bureaucracy and attitudes towards helping war widows and the British wounded. The Ministry of Pensions took over from the Admiralty, the War Office, the Army Council and the Chelsea Hospital Commissioners. It was responsible for administering all naval and military death and disability pensions and allowances, including naval and military nursing services, arising from the First World War or granted prior to 18 September 1914.

Britain sought to cut government spending to manage the national debt, which rose from £754 million in 1913 to £7,414 million in 1919. The Ministry of Pensions’ remit became to protect public spending and it developed a reputation for parsimony. It applied a strict formula to award pensions, which limited discretion to take account of an individual’s needs. In 1917, £40 million pounds was spent on disablement pensions (Ministry of Pensions, 1919) and by 1921, a total of 1.3 million pensions were awarded.

Overall, the Ministry reduced spending by almost 50 per cent, from £106,367,000 in 1921 to £54,066,000 in 1930. This reduction was achieved in numerous ways. By 1925, almost half a million pensioners, with around 50 per cent of those in receipt of a pension scaled at 20 per cent or less, were given a lump sum or gratuity defined as a ‘Final Award’. There was a subsequent reduction in medical facilities: while 332,000 disabled pensioners were undergoing treatment in 1921, this figure stood at just 41,000 by 1930. The Ministry then often covered the cost of a veteran’s health care via “Capitation” grants for treatment in public hospitals or via their personal General Practitioners. A subsequent associated reduction in Ministry staff resulted in 21,685 departmental staff in 1921, being reduced to just 3,795 a decade later.

War Gratuity

Unlike the service gratuity, the war gratuity paid an amount based on both the rank of the man and the length of service (home and/or overseas) – up to a maximum of 60 months service between 4th August 1914 and 3rd August 1919.

Service with overseas service

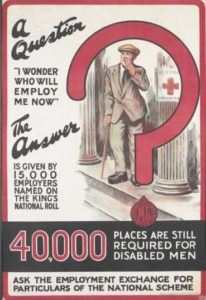

Businesses that employed the men were given preferential consideration for contracts and could display the royal crest. However, the tendency was to employ those with low level disability, leaving the severely disabled out of work. The state did not create sheltered employment opportunities or provide retraining. Britain was the only European state to rely entirely on voluntary effort to employ disabled ex-servicemen.

£5 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£5 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

Corporal

Service with overseas service

£6 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£6 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

Sergeant

Service with overseas service

£8 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£8 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

Colour or Staff Sergeant

Service with overseas service

£10 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£10 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

WO 2

Service with overseas service

£12 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£12 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

WO 1 Service with overseas service

£15 for the first 12 months service then 10s per month

Service without overseas service (minimum service period of 6 months to qualify)

£15 for the first 12 months service then 5s per month

Extract from Ministry of Pensions’ classification for military disablement pensions (Ministry of Pensions, 1919).

War Pensions

The following is a percentage of disability and % of pension entitlement, with examples of specific disability required for pension entitlement.

100% – Two or more limbs, or arm and eye, leg and eye, or both hands, or all fingers and thumbs, or hand and foot, Total loss of sight

Permanently bedridden, Total paralysis, Total permanent disablement through internal, thoracic or abdominal organs, Lunacy, Head or brain injuries which permanently disable, Very severe facial disfigurement

90% – Amputation of right arm through shoulder

80% – Amputation of leg at hip with stump, not more than 5 inches, of right arm below shoulder with stump not more than 6 inches, of left arm through shoulder, Severe facial disfigurement, Total loss of speech, Loss of both feet

70% – Amputation of leg below hip not below middle thigh, of left arm not more than 6 inches below shoulder or right arm not more than 5 inches below elbow, Total deafness

60% – Amputation of leg below middle thigh or through or not more than 4 inches below knee, or of left arm not more than 5 inches below shoulder through or not more than 5 inches below elbow, of right arm more than 5 inches below elbow

50% – Amputation of leg more than 4 inches below knee, or of left arm more than 5 inches below elbow, Loss of vision in 1 eye

40% – Loss of thumb or 4 fingers of right hand, loss of 2 toes of both feet above knuckle, Lisfranc operation, one foot

30% – Loss of thumb or 4 fingers of left hand, loss of 3 fingers of right hand

The issuing of Pensions became a slow and complex process. In 1919, the Ministry of Pensions were employing only 12,00 staff to deal with millions of claims. Payments were made from the time of the application, not the death of the victim and it could take six months before a decision was made. Payments stopped on appeal and were not backdated. Payments were often late, meagre and there was even criticism that some pensions were being decided by “seventeen year old girls”. Only servicemen with a 40-100% disability could claim a War pension. The 27s. 6d. full disability weekly payment was not enough and the flat rate for a mother who lost a son was only 5 shillings per week. Although these awards were later increased they were still inadequate. A full disablement pension of 40 shillings per week, was less than what was earned by an unskilled builder (84 shillings and 6 pence per week), a coal mining labourer (99 shillings and 3 pence per week) or a skilled coal getter (135 shillings and 6 pence per week). Pensions did not increase for dependants and there was no government plan to re-train ex-servicemen or help them return to employment.

There was also great dispute over what constituted a disability and what percentage should be awarded.

Many of the women whose husbands, fiancés, boyfriends and brothers were killed in the First World War, felt that they too had served their country by sacrificing their men to war, and that their loss deserved recognition. Women’s lives had been dramatically reshaped by these losses and left many families in financial hardship. However, only married widows were entitled to a War pension. Unmarried partners and separated wives faced many barriers. Widows had to prove their husband’s deaths were due to war service and were only awarded a portion of their husbands pension. In 1924, the original stipulation that a man must die within seven years of his injury was removed and widows could claim two thirds of her husband’s disability pension. However, confusion and disputes continued as the payment system could not account for individual needs.

Allowances paid to mothers who lost their only son, or other dependants, like a husband or other sons, could vary widely between neighbours, as well as regions. There were arguments over adequate compensation, what a man’s skills as a “breadwinner” were worth, their earning potential and what was “reasonable” standard of living. Widows were often worse off financially, than the wife of a soldier still serving. The treatment of children introduced further issues on allowances and payments. For example, no Grant or allowance was made in respect of children that were born nine months after demobilisation, yet these needed to be provided for if men were incapacitated. The payment of pensions and allowances to dependants became controversial, difficult to reconcile and caused dissatisfaction for decades. *

Many men who may have been entitled to pensions, never claimed them. Others who were originally granted pensions, tired of attending Medical Boards to be reassessed, relinquished them. The widows of these men were left without a claim, unless they could prove a continuous medical history of the complaint leading to their husband’s death and that it was direct result of war service. Even women tired of the intrusive nature of the Pension Ministry and forfeited claims.

The Ministry of Pensions main role was to protect public expenditure and evade paying pensions where possible. It went to considerable lengths to investigate cases before accepting liability. They often trawled through pre-war medical records and Friendly Society Insurance Policies to prevent claims. For example, coal miners admitting to chest troubles prior to enlisting, found claims of gas wounds rejected. The post war depression forced Governments to reduce public spending further. Compensation for “shell shock” which was not deemed a legitimate medical condition at the time, had a particular hard time securing suitable pensions. The 37,199 ex-servicemen who settled abroad via the British Government’s Overseas Settlement initiative became increasingly isolated and marginalised. (16,514 former British Servicemen, settled in Australia and around 11,500 pensioners emigrated to Canada and the USA).

Widows had to be married to the soldier at the time of injury. Men marrying widows after the war could not make a claim. The Victorian class system often prevailed. Officers were treated more leniently than other ranks and their children were given education grants to enable them to have ‘the education they would have received if their father had not been killed or disabled’.

Widows had to be seen as “deserving” and it was thought women were marrying wounded soldiers to claim a war pension. The Ministry of Pensions held all the cards. Pension claims were based on the man’s service record and these were sometimes incomplete or incorrect, but they were held sacred by the Ministry, making it difficult for claimants to dispute. For example, gas victims, after the war were refused help, because their service records referred to gunshot wounds, rather than gas. The Pension Appeals Tribunal established in 1917 was still part of the Ministry of Pensions and still put up artificial barriers to deter claims. For example, 12 Tribunals consisting of a lawyer, a discharged serviceman and a Doctor, were set up to hear appeals and disputes. However, the Pensions Appeals Tribunal was only available to those who could afford legal representation and were often located in places which deterred claimants. Portsmouth for instance, an important Naval base which had suffered many war casualties, held their Tribunal in Exeter, a long expensive train ride away, beyond the means and convenience of many impoverished war widows. The Ministry of Pensions were intrusive, stacked against poor women with little means, and often overturned Medical advice, seeing Doctors as “too soft”. They could refuse, cut and revoke pensions and had the power to remove children from their mothers for “neglect”. By March 1924, there were 18,157 orphaned children in the care of the department, there were also 3,181 whose mothers were alive; of these, 668 had been committed into care by the Special Grants Committee under the Children Act, 1908. The Pension Ministry found it easier to refuse claims of soldiers who had died in training or not seen battle, even though these home soldiers were elderly and did hazardous war work in poor conditions. For example, a 1917 Parliamentary Debate revealed 100,000 men were unfit to be conscripted, but these men were still expected to serve in some capacity. The widows of the 343 men and 3 officers who were shot for cowardice or desertion during the First World War, were left destitute until January 1918. Widows of men who had committed suicide were also refused a pension until March 1917 . Widows of men who died from disease, could also be refused a pension if ‘the man’s death from either disease or injury was due, or partly due, to his own fault or negligence’.

Many thousands of First World War widows received no pension, or had it taken away from them. Between October 1916 and March 1920, the Statutory Committee and the Ministry between them, initiated at least 40,000 investigations. In a single year between March 1918 and March 1919, 6,302 women lost their separation allowance and 939 war widows forfeited their pensions due to “unworthy” behaviour. By 1936 the numbers of war widows’ pensions being paid had fallen to 129,500 and 117,000 war widows had married again, although many widows cohabited rather than remarried as they lost their war pension on remarriage.

In 1937, when there was less scrutiny, the Ministry of Pensions withdrew pensions saying their original decision 20 years before was incorrect. This was particularly cruel for widows who had been left to care for their disabled partners largely on their own. Personal wealth greatly affected the outcome and future life chances of disabled veterans. Wealthier disabled ex-officers like Sir Jack Cohen, MP, who had lost both legs at Passchendaele, could afford to pay privately for a custom-fitted prosthesis, a motorised wheelchair, a personal attendant, a lift, home aids, and a car adapted to their needs. Meanwhile, other disabled veterans were sometimes unable to leave institutions because their families did not have access to adequate housing.

In Britain during the late 1930’s, 639,000 ex soldiers and Officers were still drawing disability pensions. This figure includes 65,000 men whose disabilities were not physical, but mental. Some servicemen were so traumatised by the experiences in the First world war, that they spent the rest of their lives in hospital. About 25% of those discharged from active service during the war were ‘psychiatric casualties’. Most were suffering from shell-shock, a condition viewed by the public as a sign of emotional weakness or cowardice. A growing number of centres, such as the Royal Victoria Hospital in Southampton and Seal Hayne in Newton Abbot specialised in such cases. When it came to housing, there was also no comprehensive government plan to provide suitable long-term accommodation. Developments in disabled housing, were largely driven by the voluntary sector, rather than the State, along with early initiatives in rehabilitation and retraining and major advances in prosthetics and plastic surgery. Some of these private and voluntary initiatives are detailed below.

Pensions Abroad.

Overall, some 15 million men were wounded in WW1 and this had enormous social, economic, demographic and political consequences. In 1919, the newly formed Weimar Republic, on the verge of wild inflation, bankruptcy, and political chaos, discovered that Germany was suddenly responsible for some 2.7 million disabled veterans, 1,192,000 war orphans, and 533,000 widows. Almost all of these people were younger than thirty and the new German Republic might be responsible for them for another half-century or more. Calculating war pensions proved expensive and contentious and only 800,000 Germans received invalidity pensions.

France had the same number of disabled as Germany, 630,000 soldiers’ relatives and about 1.4 million widows and orphans. Countries like Britain and Italy had more than a million victims. The numbers in smaller countries were far from irrelevant: in Czechoslovakia 575,000 disabled and survivors represented approximately 4 percent of entire population. The situation in Austria, Hungary, Romania and Poland was similar. In 1923, the International Labour Organization (ILO), based in Geneva, estimated around 7 million war disabled, although it did not include statistics from some countries.