The impact of war can be measured in many ways, such as the cost in lives, the financial costs and the consequences the war had on future world history.

In terms of statistical casualties, and lives lost, the First World War was the fifth most costly war in World history. All told, 16.5 million people died and 21.2 million were wounded from all combatant nations during World War 1.

The Cost in Lives

The total number of deaths during war includes about 10 million military personnel and about 7 million civilians. The Entente Powers (also known as the Allies) lost about 6 million soldiers, while the Central Powers lost about 4 million. At least 2 million died from diseases and 6 million went missing, presumed dead. About two-thirds of military deaths in World War I were in battle. This was unlike any previous conflict during the 19th century, when the majority of deaths were due to disease. Improvements in medicine, as well as the increased lethality of military weaponry, were both factors in this development. Nevertheless disease, including the ‘Spanish flu’, still caused about one third of total military deaths for all belligerents.

Britain and Commonwealth forces lost nearly 900,000 military personnel and 1.7 million men were wounded.

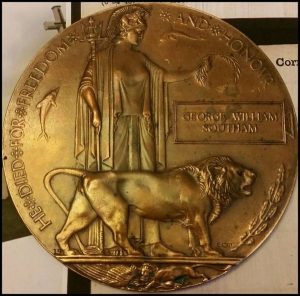

In Britain that was about 10% of the male population killed, and 70% of these men were aged between 20-24 years old. Of the 700,000 British war dead, no fewer than 71% were between the ages of 16 and 29 years. The Commonwealth War Records reveal that 14,108 British soldiers died aged 18 years or younger.

Britain’s big cities lost most men, Glasgow, 13,740; Manchester, 3,481; Liverpool, 10, 470; Birmingham, 9,842; Hull, 7,500 +, Derby, 6,952; Edinburgh, 5,281; Durham, 6,353; Leeds, 4,312; Sheffield, 4,854; and London, 41,833. But it was the northern and Scottish towns that saw their populations hardest hit. In Durham 6,300 men lost their lives. This was equivalent to almost two in ten men in the city and nearly eight per cent of the total population. Another Country Durham town, Bishop Auckland, was also it hard losing more than six per cent of just 13,600 people, all of them men between 18 and 50-years-old. Derby lost almost six per cent of its population and Dumfries, Scotland, five per cent, according to genealogy company Ancestry. Nine of the 10 towns and cities that lost the highest proportion of their population are in Northern England and Scotland.

Scotland which traditionally provided recruits for the British army’s elite regiment’s, lost 148,000 men. This was 25% of those that volunteered and more than twice the national average rate of fatalities for the whole of Britain. Over 38,000 Irishmen and 20,000 Welshmen also died in the war.

Throughout the United Kingdom, one in six families suffered a direct bereavement, 192,000 wives had lost their husbands, and nearly 400,000 children had lost their fathers. A further 500,000 children had lost one of more of their siblings. Appallingly, one in eight wives died within a year of receiving news of their husband’s death. There were also 1.7 million British wounded of which 80,000 were gas victims, 30,000 were made deaf, 80,000 had ‘shell shock’, and there were 250,000 amputees. This increased over time. At the end of 1928, nearly 2.8 million war veterans received a disability pension of some sort. While it was the big cities that lost the highest numbers of men, it was the smaller northern England and Scottish towns that saw entire generations completely wiped out.

In Germany, approximately 13 million Germans served in the military during the Great War; over 2 million or 15 percent of these, were killed. This was a demographic catastrophe for German society. Some 13 percent of German men born between 1880 and 1899 (prime candidates for service in the war), were killed between 1914 and 1918. For German women in the doomed cohorts born between 1880 and 1899, war losses meant transformed lives. For many young German women in the 1920’s, marriage and family were not possibilities; there were no young men available. This, to be sure, produced a kind of autonomy for the women affected, but, for those who had hoped for marriage and family, wartime deaths meant a lifetime alone.

After the war, the German Government reported that approximately 763,000 German civilians died during the war because of the Allied Blockade and another 150,000 died of the war-related Spanish Influenza. Total German losses, then, military and civilian, during the Great War, thus approach 3 million. The sudden and violent death of some 2 million young men confronted Germans with that peculiar 20th century phenomenon, of mass death. The apocalyptic German experience of 1914-1918, coupled with defeat, revolution, and then civil war, engendered what Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) called “absolute despair” and that obsession with messianism, apocalypse and redemption became characteristic of Weimar Germany’s culture and politics. Jason Crouthamel has explored the psychiatric dimension of this enormous trauma. For Germans, during and after the war, simply finding the bodies of the dead, and burying them properly was a vast problem.

Most of the German were either buried in mass or unmarked graves, or their graves were, after the war, in the hands of Germany’s former enemies. Germany erected innumerable local monuments in honor of their war dead, but creating a national day of mourning, with appropriate national rituals and symbols proved impossible in the politically torn Weimar Republic, and that would have devastating consequences for the legitimacy of the Weimar Republic and for German political culture.

The Wounded

Overall some 15 million men were wounded by their service during WW1 and this had enormous social, economic, demographic and political consequences.

In 1919, the newly formed Weimar Republic, on the verge of wild inflation, bankruptcy, and political chaos, discovered that Germany was suddenly responsible for some 2.7 million disabled veterans, 1,192,000 war orphans, and 533,000 widows. Almost all of these people were younger than thirty and the new German Republic might be responsible for them for another half-century or more. Calculating war pensions proved expensive and contentious and only 800,000 Germans received invalidity pensions.

In Britain during the late 1930’s, 639,000 ex soldiers and Officers were still drawing disability pensions. This figure includes 65,000 men whose disabilities were not physical, but mental. Some servicemen were so traumatised by the experiences in the First world war, that they spent the rest of their lives in hospital. The victims of the First World War were not confined to the battlefield. The attempted genocide of the Armenian people cost between 800,000 and 1.3 million lives. As many as 750,000 German civilians died as a result of the Allied Trade blockade. More Serbian civilians (82,000) died as result of the conflict, largely from disease and starvation, than Serbian soldiers (45,000).

Millions of soldiers and civilians alike were killed by the virulent Influenza pandemic that left none of the warring countries untouched in 1918 and 1919. In addition, there were the many millions of largely silent victims of the Great War: the widows, parents, siblings, children and friends who lost loved ones. Historians have only recently turned their attention to the many ways in which survivors sought to cope with the grief caused by these innumerable personal losses. During the war, in a brief essay entitled “Mourning and Melancholia,” Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) identified grieving as a complex, painful, and psychologically crucial process which had become, because of the war, an immense social problem.

Changes in Population

After the war women far outnumbered men and many were never to marry or have children. The 1921 United Kingdom Census found 19,803,022 women and 18,082,220 men in England and Wales, a difference of 1.72 million which newspapers called the “Surplus Two Million.” In the 1921 census there were 1,209 single women aged 25 to 29 for every 1,000 men. In 1931, 50% were still single, and 35% of them did not marry while still able to bear children.

In France, approximately 11% of the entire population were killed or wounded during the war. Almost 1.4 million Frenchmen died in the service of their country and another 4.2 million men were wounded – a casualty rate of 74% of all those mobilized in the French Empire. They left behind 600,000 widows, 986,000 orphans, and 1.1 million war invalids. 10% of the male population of France had been wiped out, a figure that rises to 20% for the ‘under 50’ age group. Of the 470,000 males born in France in 1890, and who were 28 years old when the war ended, half were killed or seriously wounded. In Belgium more than 40,000 young men were killed.

Much of France and Belgium, where the main WW1 battles were fought, were left devastated. The Western Front, some 250 miles long and 25-30 miles wide, had been reduced to a wasteland. 1,659 towns and communes had been blotted out, 2,363 others were wrecked, and 630,000 houses were destroyed or seriously damaged. So many mines were ruined, that the output of coal was reduced by a half. Some 21,000 factories were gutted, and the great manufacturing centres at Lille, and the Longwy district, were systematically despoiled of machinery vital to their prosperity. Even today, huge tracts of land remain cordoned off from the public and people still die from unexploded munitions left over from the war.

The Financial Cost of World War One

World War I cost more money than any previous war in history. One estimate suggests $186 billion in direct costs and another $151 billion in indirect costs, although the full cost is complex and may never be fully known. The Allies had much more potential wealth they could spend on the war. Another estimate (using 1913 US dollars) is that the Allies spent $147 billion on the war and the Germans and their allies, only $61 billion. Among the Allies, Britain and its Empire spent $47 billion and the U.S. $27 billion (America joined the war in 1917) while among the Central Powers, Germany spent $45 billion.

Before World War One, Britain was the world’s economic superpower. With rapid growth and a vast empire, the country enjoyed significant levels of wealth and resources. However it wasn’t ready for the economic impact war would have.

In contrast, Germany’s 1912 budget had approved rising military expenditure until 1917 – effectively militarising their economy ahead of the conflict.

When war erupted in the summer of 1914, Britain faced market panic and a massive financial crisis. Not only did the government need to reassure the markets, it had to prepare itself for the huge economic demands of total war. Facing the financial strain of war, the government had to find ways of raising money. They had three main economic tools at their disposal:

Taxes

Although indirect taxes raised some money, the government turned to direct taxes – on property and income – on a far greater scale. In 1913 income tax was only paid by 2% of the population. During the war, another 2.4 million people would end up being eligible so by 1918, 8% were paying income tax.

Borrowing

This took the form of big international loans but also borrowing from the public through the war bonds scheme. Big promotional campaigns were used to inspire the country to invest in the war effort.

Printing money

Freed from the Gold Standard by the Currency and Bank Notes Act of 1914, the Bank of England was able to increase availability of money by printing it, even though this risked contributing to inflation – rising prices.

In the United Kingdom, funding the war had a severe economic cost. From being the world’s largest overseas investor, Britain became one of its biggest debtors with interest payments forming around 40% of all government spending. The economy (in terms of GDP) grew about 7% from 1914 to 1918 despite the absence of so many men in the services; by contrast the German economy shrank 27%. The War saw a decline of civilian consumption, with a major reallocation to munitions. The government share of GDP soared from 8% in 1913 to 38% in 1918 (compared to 50% in 1943).

Inflation more than doubled between 1914 and its peak in 1920, while the value of the Pound Sterling fell by 61.2%. Reparations in the form of free German coal depressed local industry, precipitating the 1926 General Strike. The Versailles Treaty set German repayments for the cost of the war at 132 Billion Marks. This was to be repaid in cash or raw materials, land given up and services provided. These repayments were suspended in 1932, by which point Germany had repaid only 20.5 Billion Marks (about $6 billion).

British private investments abroad were sold, raising £550 million. However, £250 million in new investment also took place during the war. The net financial loss was therefore approximately £300 million; less than two years investment compared to the prewar average rate and more than replaced by 1928. Material loss was “slight”: the most significant being 40% of the British merchant fleet In sunk by German U-boats. Most of this was replaced in 1918 and all immediately after the war.

Although Britain was ultimately victorious, the effects of war would be felt for many years to come. Foreign trade, a key part of the British economy, had been badly damaged by the war. Countries cut off from the supply of British goods had been forced to build up their own industries, so were no longer reliant on Britain, instead directly competing with her. In 1920/21, Britain would experience the deepest recession in its history.

World War One was a significant moment in the decline of Britain as a world power. It would be gradual, but by the mid-20th century the United States would usurp Britain as the leading global economic power.

Today, nearly £2 billion worth of WW1 War bonds are circulating in the market. War bonds originally paid an interest rate of 5%, but in 1932, as the government battled against a budgetary crisis, the then Chancellor Neville Chamberlain changed the terms of those bonds. He appealed to holders to do their patriotic duty and voluntarily accept a cut in the interest rate to 3.5%. All but a small minority agreed the terms – and that wasn’t their only sacrifice.

War bond holders also agreed in effect to accept that they might never get their investment back. Whereas the original bonds had been due to be repaid in full in 1947, Chamberlain converted them to “perpetuals”, giving the government the right not to pay back the loans if they so wished, as long as they continued paying the 3.5% interest.

Surprise, surprise – no government since the 1930’s has chosen to repay these bonds. There are believed to be about 125,000 holders – some of whom might have inherited them from parents or relatives who bought them during World War One.

The continued existence of the war bond debt is possibly the most graphic illustration of the lasting shadow cast by World War One.

The Commonwealth Nations and Ireland

The Commonwealth nations which supported Britain during WW1, lost 250,000 men killed and 500,000 wounded. New Zealand lost 18,000 killed and 50,000 wounded out of the 112,000 who served. This was a casualty rate of 66%. Australia’s casualties were 80,000 killed and 137,000 wounded, 64% of those who joined. Similarly, Canada and Newfoundland lost 62,000 and 172,000 wounded, a casualty rate of 39%; South Africa lost 7,000 killed and 12,000 wounded, some 13% of those who served. It is estimated that 1.5 million Indian troops fought to defend Britain. Of those, 400,000 were Muslim soldiers. In all India lost 74,000 men and 67,000 were wounded, about 7% of those that served. In addition, 100,000 men from the African and Caribbean Colonies who acted as carriers and labourers died of disease and exhaustion, with another 18,000 killed in action. Nearly a million people in Kenya, for example, served Britain, either in the carrier corps, or in the King’s African Rifles. That was one quarter of the population. In places like the Voi region, 75% of African adult men were involved in some form of military activity

There was growing assertiveness amongst Commonwealth nations after World War 1. Battles, such as Gallipoli, for Australia and New Zealand, Vimy Ridge, for Canada, Neuve Chapelle for India, led to increasing national pride and identity. There was a greater reluctance to remain subordinate to Britain, leading to the growth of diplomatic autonomy in the 1920’s. Loyal Dominions, such as Newfoundland, were deeply disillusioned by Britain’s apparent disregard for their soldiers, eventually leading to the unification of Newfoundland with the Confederation of Canada. Colonies, such as India and Nigeria also became increasingly assertive because of their participation in the war. The populations in these countries became increasingly aware of their own power and Britain’s fragility.

In Ireland, the delay in finding a resolution to the home rule issue, partly caused by the war, as well as the 1916 Easter Rising and a failed attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland, increased support for separatist radicals. This led indirectly to the outbreak of the Irish War of Independence in 1919. The creation of the Irish Free State that followed this conflict, in effect represented a territorial loss for the United Kingdom, that was all but equal to the loss sustained by Germany, (and furthermore, compared to Germany, a much greater loss in terms of its ratio to the country’s prewar territory). Ireland lost over 38,000 men in the war. Many more Irishmen died, serving with British regiments and the Commonwealth nations. The true casualty figure may never been known. There was no triumphant welcome for Irish Soldiers returning to Southern Ireland. They were were largely shunned and met open hostility for supporting Britain during the war.

The Changing Views of WW1

No war in history had demanded so much, mobilised so many, or killed in such numbers. When it was over, the men who fought began to ask questions “What was it for?” and “Was it worth it?” The way we think about the war has changed dramatically over the last 100 years since it ended. In Britain, many myths, opinions, politics and propaganda surrounding the Great War, shaped the way it was remembered. We no longer know what we feel about it, or even if we should celebrate it. Was the ‘Great War’ a triumph or an unspeakable horror? Do we side with the War Poets that highlighted the war’s futility, or the Politicians and Generals, who resisted German militarism? We can not even agree how World War should be taught in schools. It has been a cultural battlefield for every generation that followed. Even different countries remember World War 1 in different ways. In Germany, which lost over two million men, the First World war is largely forgotten and has been superseded by the Second World War. Each new generation reinterprets WW1 in the light of their own values.

Armistice Day – A series of stunning Allied victories in the last hundred days of the war, had thoroughly exhausted the German army. Faced with starvation from the Allied Naval Blockade and revolution at home, Germany sued for peace. The two sides met in a railway carriage in the French forest of Compiegne. After three days of negotiation, Germany reluctantly accepted the Armistice terms. No one shook hands. Germany agreed to surrender all their Navy to Britain, leave all occupied land, and hand over vast quantities of weapons, equipment and prisoners. They also ceded the Alsace-Lorraine territory in the Rhineland to France, so that they too, would learn what it meant to be occupied. The Armistice was to begin at 11am, on the 11th November, 1918. It was a Ceasefire, not an end to the war. News of the Armistice did not reach Kenya for another two weeks, where fighting raged on until the 25th November. The armistice initially expired after a period of 36 days. A formal peace agreement was only reached when the Treaty of Versailles was signed the following year.

Designed by Edwin Lutyens, the permanent structure was built from Portland stone between 1919 and 1920 by Holland, Hannen & Cubitts, replacing Lutyens’ earlier wood-and-plaster cenotaph in the same location. An annual Service of Remembrance is held at the site on Remembrance Sunday, the closest Sunday to 11 November (Armistice Day) each year. Lutyens’ cenotaph design has been reproduced elsewhere in the UK and in other countries of historical British allegiance including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Bermuda and Hong Kong.

It is estimated that some 5,000 troops still died on the 11th November 1918, the final day of the First World War. It is believed that Private, George Edwin Ellison, of the 5th Royal Irish Lancers, was the last British soldier to be killed at 9.30 am. Aged 40, he died on the outskirts of Mons, ironically where his war had began in 1914.

The Allies decided not to continue with war. They feared that Germany would defend the Rhineland and that more lives would be lost. They were reluctant to occupy a Germany on the verge of civil war and revolution. They also did not want to see a strong America, which was planning to bring 3 million more troops to Europe, dictating the Peace terms.

The news of the Armistice did not reach everyone at the same moment. There were on Televisions, radio or social media to spread the news, back then. News of the Armistice spread by word of mouth, from town to town, village to village, by proclamation, newspapers and by telegram. The news was met with mixed emotions world wide, a combination of relief, sadness and pride. War Diaries suggest that soldiers at the front took some time to adapt to the Armistice news. They continued with their daily routine of sentry duty and cleaning of rifles, perhaps in bewilderment of what would happen to them next?

In London, news of the Armistice, sparked spontaneous outbursts of joy and celebration. While it was a time of sadness and mourning, the ending of the war was seen as a victory and there was great pride felt towards all the sacrifices made. Workplaces emptied, large crowds took to the streets. There was collective singing, dancing, some drinking and general merriment. The King stood on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to rejoice with the crowds below. Lloyd George, the Prime Minister, addressed Parliament, hoping that the Armistice would be “the end of all wars”. Church bells began to ring, “Big Ben” which had been silent throughout the war, chimed again, “Peace at Last” was the headline on the newspaper billboards. The general excitement of the Armistice news, is captured in the newspapers of the time.

“Processions of soldiers and munition girls arm in arm were everywhere.” (DAILY MIRROR, NOV. 12, 1918);

“American soldiers in jubilation invaded Downing Street.” (DAILY MIRROR, NOV. 12, 1918);

“At Buckingham Palace, dense crowds were shouting ‘We want the King!’ The King, the Queen, Princess Mary and the Duke of Connaught appeared on the balcony and His Majesty spoke a few words. Indescribable scenes of enthusiasm followed.” (DAILY MIRROR, NOV. 12, 1918)

Sir Edwin Lutyens, the English Architect designed the Whitehall Cenotaph in 1919. Lutyens rebuilt the Cenotaph in white, Portland stone and went on to design many other memorials in Dublin, Manchester, Leicester and the Thiepval Memorial to the missing in France.

For many years, most people were keen to remember the two million dead, missing and wounded. Thousands of memorials were built throughout Britain, and many expressed words, like

“Victory”, “Honour”, “Freedom” and “Glory”. This reveals a strong National pride that the sacrifices made would save the world from further wars. Unlike today, Britain’s civilians were unable to watch the war unfold on television, or properly understand it’s horrors. Sometimes there was the distant sound of gunfire across the channel, but most opinions were framed by war time propaganda. The silence of the returning war veterans only added to the Great War’s mythology. This created mixed views about the war. While some saw the War as futile and an end to stability, many others saw it as a National celebration and revelled in the excitement and opportunities that the war brought. Soldiers celebrated war time comradeship through regimental reunions and by joining the British Legion established in 1921. War time Generals, such as Sir Douglas Haig, were seen as a National Saviour and his 1929 funerals in London and Edinburgh, attracted over a million mourners. The Whitehall Cenotaph, was erected in 1919 to remember Britain’s ‘Glorious Dead’. The Nation would stop for a two minutes silence at 11 am, every Armistice Day – on the 11th November. The Cenotaph became a popular and successful memorial and many Cities, like Hull, built their own Cenotaph. They provided a blank canvass for the British people to project their mixed feelings about the war.

The catastrophic losses and tragedy, ensured that the 1914-18 war became known as ‘The Great War’, or the ‘War to End all Wars’. British Politicians that had sent so many young men to their deaths formed a ‘League of Nations’. They hoped that this would provide the machinery to negotiate future disputes and prevent war happening again. Veterans and Civilians argued for more democracy and rights – “A Land fit for Heroes”. Once subjects of the Crown, the word “Citizenship” emerged in the 1920’s and 1930’s, which reflect people’s rights and desire for better housing, health and employment. Government’s concerned about the “Russian Revolution, the rise of Socialism, the growth of Trade Unions and the Labour Party were keen to appease these demands. Land was set aside for public housing, social security benefits were extended and women were given an equal vote in 1928.

1930’s – In 1928, on the 10th anniversary of the ending of the Great War, Britain again reflected on the War experience. West End Plays, like ‘Journey’s End’, and the publication of many memoirs, such as ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’, ‘Cry Havoc’ and ‘Death of a Hero’, revealed the true horrors of the Great War. The terrible sacrifice, and pointless slaughter prompted a revulsion to war. A British pacifist movement established in the 1920’s, grew during the 1930’s. Some campaigned for disarmament and economic sanctions against military aggressors. Others campaigned for appeasement. Many organisations, such as the ‘No More War Movement’ and the ‘Peace Pledge Union’ were established to totally denounced war. This was to leave Britain very unprepared when the next World War began in 1939.

Post WW2 – In 1948, the British Government renamed the ‘Great War’, the ‘First World War’, to distinguish it from the ‘Second World War 1939-45’. ‘Armistice Day’ was also replaced with ‘Remembrance Sunday’ to remember those lost in all wars. These changes were significant. It highlighted that the the Great War was not the “War to End all Wars” and made people re-evaluate the purpose of the World War 1.

The 1960’s –

The 1960’s generation shaped our view again of the war. 1964 was the Great War’s 50th anniversary. It was a chance for a new generation to discover World War One afresh, and their version of the war was futile. The emergence of a youth culture in the 1960’s viewed the war through the tinted nightmare of World War Two, the Vietnam War, and the possibility of a new nuclear war caused by the ‘Cuban Crises’. The 1960’s was a more egalitarian and less deferential generation. They mocked the attitudes of predecessors. They were more interested in the individual experiences of ordinary soldiers, rather than the posturings of upper class politicians and generals. Sir Douglas Haig once a National Hero, was now labelled as as a Villain, “The Butcher of the Somme”, and responsible for the needless deaths of thousands of young men.

The release of the 26 part, television documentary, ‘The Great War’, brought a ‘dead’ conflict back to life. Books, such as Alan Clarke’s, ‘Lions led by Donkeys’, and plays like ‘Oh What a Lovely War’, savaged the futility of war and also satirised the class war within it. Academics reevaluated the Great War, as a war with no moral justification, or clear cause. It’s pointless carnage was only illuminated by the rediscovery of the long forgotten war poets, who had served in the trenches and highlighted the horrors, first hand. These poets now defined the war for an Anti War 1960’s generation. War Poems which questioned Patriotism, and the competence of Generals and Politicians, chimed with the times. Carefully edited selections of war poetry were repackaged, showing a poetic learning curve from Rupert Brook’s innocent patriotism, to Siegfried Sassoon’s angry satire and then Wilfred Owen’s bleak pity and horrors of war. Britain’s obsession for the soldier poets, would shape how World War One was taught in schools and would be publicly remembered. The Great War would now be defined by the horrors of trench life on the Western Front. The ‘Blackadder Goes Forth’ comedy series, which lampoons British Generals, and has been used as a teaching aid in schools, still echoes public perceptions of the First World War.

Recently – On the 25th July 2009, Harry Patch, the last British soldier to serve in the trenches, died, aged 111. The last living British veteran of the war, was Florence Green, who served in the armed forced, and died on 4th February 2012, aged 110. In a way, the deaths of these last survivors, marked the end of the twentieth century. Future generations will no doubt look at the First World war through Twenty first Century eyes, with a greater awareness of disability, and more empathy for the consequences of war, like stress, divorce and bereavement. The staggering loss of ten million soldiers, in largely static warfare, cannot fail to move people. Rather than accepting just one view of the war, people now take a wider perspective. There’s a keen interest in the “forgotten” stories of the war. Many people are researching their families, on line, and reconnecting with their relatives from the First World war. Community groups are springing up to discover how the war affected their local town, or village. Many are also rediscovering the diversity of World War 1 – the pioneering role of women in the war, the stories of Chinese labourers, Indian Sepoy’s, West Indians, Africans, Aborigines, Maoris and Native Americans, who also served in the conflict. Archive “black and white film” of the war is now being restored in colour, breathing new life, depth and colour into the generation of 1914-1918. An explosion of commemorative events between 2014-2018, reveal people, throughout the world wide, keen to remember the Great War, in their individual ways. These may include Commemorative Poppy displays at the Tower of London or “Beach drawings” in Britain and Ireland. Such events have introduced the First World War to new audiences, in new ways. Whether these commemorations are sustainable remains to be seen. Just as no one commemorated the Napoleonic Wars in 1914, it is possible that the First World War will also fade into History. However, this is unlikely in the short term. The First World War was a watershed moment in World history, and will always be remembered for the global social change it brought forward. The First World War also remains a painful reminder to the dangers of Imperialism, Nationalism and misplaced Patriotism.

The Legacy of the Great War

While the meaning of the Great War has changed over time, it is possible after 100 years to take a more balanced view. It is becoming accepted that the Great War was not a ‘bad’ or ‘unjust’ war, at least from an Allied point of view. It was fought against military aggression and to protect the sovereignty of small states, as well as the integrity of British power. The war had a powerful democratising affect, with people who fought it, demanding a new place in society for the ordinary citizen. The Britain we’ve inherited today and it’s citizen democracy grew out the sacrifice of World War 1. What went wrong was the bad peace that followed WW1. We can now remember the scale of sacrifices made at the time, the moving stories of the “Pals’ regiments, the horrors of battles, such as Gallipoli, the Somme, and Passchendaele, without allowing any doubts about the justice of the war, preventing our respect for the fallen.

The legacy of the Great War still has an enduring resonance. While the War helped postpone domestic strife and unite the United Kingdom between 1914-18, the war made Britain very wary about intervening in Europe again. Britain is still divided whether it should be part of Europe today. The War also widened the world and made politics international. Many of the current problems in the Middle East can be traced to the boundaries and territories that were drawn up directly after the First World War. The War forced America to emerge from isolation, and become the World Superpower which dominates today. The War replaced old Empires and military autocracies with democratic Nation States. Government’s expanded their powers and responsibilities to win the war and we all now accept greater State intervention, in terms of managing our health, welfare and taxation. Women achieved the vote and more political rights through the First World War. The War generated a quantum leap in industry, technology, medicine, culture and international politics. After World War One, Revolution, Republicanism and Fascism flourished. Old Empires fell apart and gave rise to mass democracy. People rose up and three visions emerged to harness ‘people power’. These were Bolshevism and the one Party State, Liberty and Republicanism, with no place for monarchs and aristocrats, and Fascism, with the cult of the Great Leader. These ideologies which emerged from the First World war, dominated the Twentieth Century and still shape ideas today. It is for these reasons that the First World War will always be remembered.