Serre was one of the last attacks of the fateful Somme campaign, and while history has rightly remembered the 1st July as being a horror story of monstrous proportions, little has been made of the Hull Pals attack at Serre.

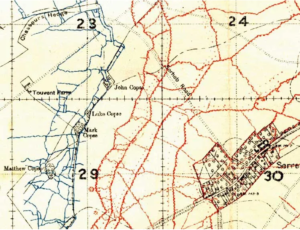

The overall British plan was to attack over a reasonably compact front, with XIII Corps in the north, between Hebertune and Serre, tasked with protecting the flank of V Corps. Their area of attack was a line running southwards and slightly east, between Serre to Beaucourt, on the edge of the River Ancre. The aim was to advance across some 500 meters, seize the Le Transloy Ridge and capture four fortified villages: Beaumont Hamel and Serre, which had been British objectives on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, as well as St Pierre and Beaucourt. On Monday, 13th November 1916, the Hull Pals were tasked to attack German positions around the fortified ruins of Serre. They needed to overrun three lines of German trenches and flatten out a dangerous salient between the Albert-Bapaume road and Serre, with the village of Beaumont-Hamel at its head.

British forces had attempted to seize this high ground during the previous month. They had been held back by heavy rain that transformed the devastated landscape of the Somme battlefield into one huge swamp. Snow and sleet added to the intense suffering of the infantry. Much of the battlefield was now a near featureless bog and a layer of ice had formed over the top with men suffering from exposure.

A 48-hour preliminary bombardment began on the 11th November, and the brigade moved into the trenches on the night of 12/13th, along communication trenches clogged with mud. Poor weather conditions prevented the Royal Flying Corps from carrying out reconnaissance flights as rain and low cloud made visibility poor. They were therefore unable to report that the bombardment had not cut the German barb wire in many places and that the fortified ruins of Serre remained in tact. Torrential rain had turned the ground into glutinous mud and a vast sucking swamp.

At midnight the 12th and the 13th EYR (3rd and 4th Hull Pals), left their waterlogged trenches and crept forward “hugging the barrage”. They were covered by thick, wet, fog. Snipers and Lewis gunners followed in support. The 12th EYR were on the left, attacking two trenches, and the 13th EYR were on the right, attacking three German defence lines. They lay in no mans land waiting for the main attack to begin at 5.30am, on 13 November 1916.

The Hull pals attacked the slope towards Serre, in cold, wet muddy conditions. The 12th and 13th East Yorkshire led the way up the slope towards Serre, with 11th Bn in close support and 10th EYR providing flank guards and carrying parties. The attack was hampered by thick fog, light rain and a smokescreen, which reduced visibility to a few yards. Officers were unable to recognize landmarks, and many units became mixed up. Initially the two Hull battalions had little difficulty. The Germans had developed a tactic of abandoning front line trenches during heavy bombardments and the Germans holding these trenches were not expecting an attack in such appalling weather. This meant that 12th Battalion took their two trenches within 20 minutes Over 300 prisoners were captured and sent back. They accounted for more than a thousand German casualties. Thirteen men received awards for bravery. Captain Mason, Lieutenant, Burch, 2nd Lieutenant, Dann and CSN, Bamford received the Military Cross for bravery. Sergeants, Freeman, Dewson , Walters and Aket and Private Spafford, were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Sergeants, Chapman and Chester and Privates Cotton and Kerry received the Military Medal.

The first wave of 13th EYR also took the German front trench. However progress was slow. The Hull Pals were laden with grenades and ammunition, and simply sank in the mud. They were also unable to keep up with the creeping artillery barraged. They found that the artillery barrage had “churned” the ground and not cut the wire or destroyed the German dugouts built deep below the villages near the front-line.

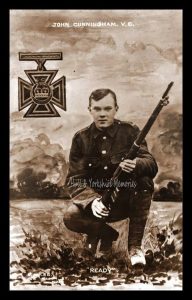

The Hull Pals continued to advance and attack through this mud, sinking in places up to their calf’s, knees and chests. They were met by stiffening German resistance and mown down by machine gun and artillery fire. They staggered breathlessly forward, wave mixed with wave. Troops which did reached the second Trench were severely depleted and confusion reigned when some German troops wanted to surrender and others refused. Poor visibility meant the Hull soldiers could not see the white tapes laid to show gaps in the wire. German machine gunners mowed down troops bunching together to pierce gaps in the wire. There were many acts of bravery as the 13th EYR stormed the second German line of Trenches. It became a memory of bayonet plunge and exploding grenade. The battalion took over 200 prisoners, but a number of these escaped in the confusion. Where the Hull men broke into the German trenches, there was fierce hand to hand fighting. Bombers cleared out the German dug-outs and collected prisoners. Private, Jack Cunningham won the Victoria Cross, aged 18, bombing a trench, almost single handed, while all his comrades were wounded.

The 2nd and 3rd waves of the 13th EYR went through without difficulty, but by the time that the 2nd wave had reached the German 2nd line, the supporting battalions (2nd Suffolk Regiment) on the right had got into difficulties, owing to unstable ground and machine gun fire. The 3rd wave of the 13th EYR took the German 3rd line, but what happened after this is uncertain. They were counter-attacked from their right and cut off, with about 50 men and 1 officer being taken prisoner. Two platoons breached the German wire, but were never heard of again. German Intelligence after the battle suggests that about 10-12 Hull Pals, finding more stable ground managed to reach the Serre village itself, but were quickly captured.

Many acts of bravery went unrewarded in the confusion. For example, Second Lieutenant, John Wood, 13th EYR, was mentioned in despatches for his great bravery, but never received an award. However, CSM Sandilands and Lance Corporal Fletcher were awarded the DCM and nine Military Medals were also awarded for gallantry in the field. (These medals went too Corporal Annable, Lance Corporals, Levitt, Howlett and Fisher, and Privates, Beacock, Chatterton, Mumby, Neylon and Smith.)

Without support, the third wave of 13th EYR were unable to hold the German third line. They beat off at least 3 German counter attacks, but were forced to withdraw to the second line, which they held until 2pm. After this parties of the 13th EYR retired to the German 1st line, which they held until 8.45pm. From 9.45am to 6pm, the Germans barraged all British lines and in particular Caber Trench, where the Battalion HQ were based. (Even friendly fire disabled eight men when a British shell fell on the HQ). Elsewhere, a Lewis gun team from 10th EYR stopped an attack on the left flank of 12th Bn and killed about 60 Germans. Corporal Edlington was awarded the DCM for his work. Sergeant, Best and Corporal, Nunns, of the carrying parties received the Military Medal for their Bravery.

While the 12th and 13th EYR tried to hold on in the captured trenches, the enemy barrage meant it was impossible to get them supplies or reinforcements. The supporting battalions of 3rd Division to their right, lost direction in the darkness and could not get across No man’s land in the deep clinging mud. Some supporting battalions, such as the 2nd Suffolk Regiment, lost so many men in trying to advance in the mud, that there was no point in attempting to reach the German trenches, as the few survivors were too exhausted to fight. A regimental officer of the 7th Lincolnshire’s later wrote that: ‘Our orders to move up were hampered by the terrible conditions. We stopped constantly to help pull men from the mud, no amount of urging would get them (the infantry) to abandon a comrade who was stuck fast. As a result we were late and few in number by the time we reached our jumping off point and the men were completely exhausted. This before we even started to advance.’

On the right, the 8th EYR (part of the 8th Infantry Brigade) attacked in the second line against Serre. The attacking battalions again struggled through mud that was at times waist-deep, and got left behind by their protective creeping barrage. In the second line, the 8th EYR had the furthest to go, across 1,000 yards (910 m) of broken trench bridges and shell-torn ground before they reached the front. As they filed forwards, the German counter-barrage caught D Company coming up from the rear. The battalion then followed the leading wave. Both waves struggled through gaps in the

wire and across the German front line. Parties of all four battalions of the 8th Brigade reached the German support line, but could not maintain themselves there; others got mixed up in the confusion at the German front line. Without support the Hull Pals were forced to retire to the first trench around 3pm. The whole mass of men tumbled back to where they started. Zero hour had been at 05.45, but by 4.30pm, all Serre operations had stalled. By 06.30pm it was clear at Brigade HQ that the battle was over. In the words of the Official History: ‘the troops of the 3rd Division … lost the battle in the mud’. The weather and deteriorating ground conditions had proved as much of an obstacle, as the German Army.”

Small-scale fighting continued all day, with the Hull Pals stranded in shell holes, resisting German counter attacks, bombardment and enemy snipers. Some soldiers went forward into the gloom to help rescue survivors. Others returned from “No Mans Land”, under the cover of darkness. After dark, the final withdrawal began, the last two parties of the Hull Pals coming in about 9.30pm. By now the British troops were suffering from exposure and all along the line, units were pulled back to be replaced by fresh troops.

By the end of the 13th November, the Hull Pals had been driven back to its starting positions and suffered over 800 casualties, mostly in the two attacking battalions. Soldiers Died records reveal that 395 men who were killed enlisted in Hull. Many more would die later of wounds.

. The 12th East Yorkshire Battalion lost 106 men. 77 killed and 4 died of wounds. Only two of the 16 officers of 12th EYR who had gone into the attack remained unwounded. (8 officers were killed and 2 later died of wounds). These Battalion War Diary losses were under reported. “Soldiers Died” records, show that 185 men killed with the 12th EYR enlisted from Hull.

. The 13th East Yorkshire Battalion lost another 138 men killed. 12 died of wounds. Plus 10 officers, (8 killed and 2 died of wounds). “Soldiers Died” records, show 165 men from Hull died with the 13th EYR in the attack.

. The 8th East Yorkshires which contained many men from Hull and Beverley, lost 2 officers killed and 3 wounded, 23 other ranks killed, 177 wounded and 30 missing. “Soldiers Died” records reveal that 25 men killed with the 8th EYR, enlisted in Hull..

. The 10th East Yorkshires, lost 6 killed, 34 wounded, 1 wounded and missing (later known to be killed). 4 died of wounds. “Soldiers Died” records, show all 10 men killed with the 10th EYR, were from Hull.

. The 11th East Yorkshires, had 12 killed, and 2 Officers and 41 other ranks wounded. 4 of the wounded died of wounds. “Soldiers Died” records, show ten of those killed were from Hull.

Among these casualty statistics are many tragic stories. They include Hull brothers, George and John Betts, and George and John Haldenby, who died the same day. Brothers, Arthur and Henry Beanland, George Alfred Smith and John Lawson Smith, all from the 13th EYR and Charles and Ernest Robinson, of the 12th EYR, who died together, in the same attack. Best friends, George Williams and Harold Shepherdson, of the 13th EYR, who died trying to save each other. Mark Wilson, killed with the 13th EYR, who had already lost two brothers in 1915. Ebeneezer Ellington, who died, leaving six young children. Albert William Pregden, 10th EYR, an only son, who enlisted underage. He is the only Pregden to die in WW1 and his family name died with him. Not all men were young, Sameuel Blakestone, was a former sailor who joined the 12th EYR and died in the battle, aged 44. Many men disappered in the mud and remained unrecovered. However, the remains of Charles Booth, 12th EYR were found on the 8th September 1920 and buried at Serre Cememtery, No:1.

There were many wounded who soon died of wounds, like Reginald Fitton, 10th EYR who died on 26/11/1916; Francis Reeve Hicks, 12th EYR, who died on 12/01/1917 and Private, Henry Wright Taylor, 12th EYR, wounded in the thigh and died of wounds in Hull, on 25/03/1919, aged 37. Similarly, John Akester Hodgson, 12th EYR, wounded, and taken prisoner, who died of wounds, years later, on 27/02/1918. Others, like, Edward Roberts, 13th EYR, who died in captivity on 03/12/1916 and Soloman Sole, 13th EYR, who died a prisoner of war, on 05/05/1917. There were also casualties never recorded like, Charles Eyre, 12th EYR, wounded in the right arm at Serre, discharged from the army on 05/09/1917 and died in Hull, on 26/08/1918, aged 28. He does not appear in any CWGC records. Also, those that survived the Serre battle, only to die six months later, when the Pals attacked again, at Oppy Wood, on 3rd May 1917. They included Sergeant, Harry Wilkinson, MM, who won the Military Medal at Serre, for storming a trench, capturing a gun and taking prisoners, who died trying the same, at Oppy Wood, in 1917. Even Jack Cunningham, who won the Victoria Cross, returned from Serre, never the same man again. He died young, after a very turbulent, post war life. Many of these men were the “The Hull Originals”, the volunteers of August and September 1914, that had queued to enlist, outside Hull City Hall. However, they were not all born in Hull. Some like, James Francis Brocklehurst, of the 10th EYR, was born in Vancouver, Canada, Sergeant, John Francis Walton, 11th EYR, was born in Cairo, Egypt; Percy Walter Huntley, of the 12th EYR, was a Londoner, Thomas John McNally and Francis Tulley, both from the 13th EYR, were born in North Ireland. The casualties therefore, had a wider affect, outside the City of Hull. Many Hull Pals now lie buried in a number of cemeteries around Serre, which were created in May 1917 when the Germans withdrew from Serre.

The news of Hull’s losses, sent shock waves through the City. Even though newspapers were censored, long casualty lists, printed over the following days, weeks and months, could not hide what happened. Reports from soldiers returning from the front, and discharged wounded servicemen, plus the rush of over worked “Telegram Boys”, reminded civilians of the brutality of war.

On the first anniversary on the Battle of the Serre, the Hull Daily Mail, printed many sorrowful messages, under the heading, “In Proud and undying Memory of the 13th November 1916” (Hull Daily Mail, 13/11/1917, page 3). The memoriam section on the back pages of the Hull Daily Mail, provided many moving verses and poems from bereaved friends, families and loved ones. Even a hundred years later, the reader cannot fail to be moved by reading these personal expressions of remembrance.

The Hull Pals attack on Serre was a failure and soon forgotten. It was overtaken by successes elsewhere. The 51st Highland Division for example, took Beaumont Hamel, the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division took Beaucourt and the 1/1st Cheshire Regiment distinguished itself by taking St Pierre. These successes were achieved at high cost. Some 44,ooo British infantry had lined up for battle in the morning, on the 13th November 1916. By the end of the day, there were some 22,000 casualties, mostly missing. The Germans lost approximately 45,000 casualties, including 7,000 prisoners.

Over the four month Somme Campaign, the Allies had advanced some seven miles on the Somme. Bapaume, a first week objective, remained in German hands. Historians agree that the Somme, cost the Allies almost 624,000 casualties – nearly 420,000 of them British. The Germans counted their casualties differently, with estimates ranging from 680,000 – exceeding the Allied total – to 500,000. Allied commanders had finally conceded that the Somme offensive no longer provided a realistic chance for decisive victory.

The village of Serre was evacuated by the Germans in their withdrawal in February 1917, but again lost to them on the 25th of March 1918. It was retaken when the Allies advanced again on the 14th of August 1918. Serre today is just a small cluster of houses and a farm on the D919 road. The area west of the Serre village has a number of small cemeteries, which were started in May 1917. Serre also contains the remains of trenches, and the Sheffield Memorial Park which was opened in 1936 (The City of Sheffield adopted the village of Serre, after also suffering severe losses on the Somme).