In Hull, income tax increased as did the number of people paying it. Whilst wages improved, many goods were more expensive and became un-affordable. Income tax increased five times between 1914-1918 and was paid by twice as many people. It would never fall to pre-war levels again. During the war, prices increased on all the basics: rent, fuel and clothing, as well as food. However, food prices increased most sharply and continuously throughout the war, sometimes at an alarming rate. Food prices overall rose by 60%, sugar, eggs and meat prices increased by 400%. By 1917, bitter beer was 5 times the price it was in 1914. In 1918 there was a further increase in the duty on spirits, beer duty was doubled. As beer became scarce, publicans stopped serving pints; landlords were selling beer by the glass which equalled a third of a pint. ‘Government’ beer was not popular. Many farmers in Hull and East Riding produced their own beer for their workers.

Food became a growing concern for people, not just the quantity, but the quality. There were no fridges or freezers to preserve food, all food was perishable, and therefore had to be brought fresh and daily. Food became increasingly scarce due to enemy attacks on shipping and a poor harvest in 1916. These shortages provoked frustration, food queues and hoarding. Parliament announced in 1916 that there were only six weeks of food left in the country. The Government limited the number of food courses that could be served at meals in restaurants and hotels. In 1917 the harvests also failed in France and Italy. Considerable supplies of food also had to be diverted to those countries. This reduced the quality of bread in Britain. No one liked ‘War Bread’ which was said to cause “rashes, indigestion, dysentery and lowering of body strength”, and an investigation was ordered. The price of flour had soared. There was a prohibition on baking ‘light pastries’ but cakes, buns, scones and biscuits were permitted providing they had only 15% sugar. It was noted with envy that in Hull people could still buy cheesecakes, lemon and jam tarts, but not in Beverley. A bacon famine was feared because of the cost of feeding pigs, and an outbreak of swine fever meant lots of healthy pigs were slaughtered. However, by the summer of 1918 bacon and ham were released from rationing. Horses were requisitioned to pull artillery, ambulances and supply wagons. In the first few weeks of the war 170,000 horses had been supplied to help the war effort. Prices dropped drastically. A horse sold pre-war for £2,000, in 1915 resold for £105. The loss of thoroughbred horses caused concern about the future of horse breeding as over 250,000 had been killed by May 1917.

To prevent Britain being starved into submission, the Government built more merchant ships, developed the convoy system, set up the Women’s Land Army and introduced allotments, to help increase food production. 250,000 land girls, 84,000 wounded soldiers and 30,000 prisoners of war were put to use on the land, but they only increased the a surplus of food to last Britain for one more month. Many of today’s allotments were originally established during the First World War. The East Riding War Agricultural Committee was created to increase food production. Beverley got its first allotments in 1914 amid fears that food stocks would not get the nation through to the next harvest. The local papers always had information on how to grow food, agricultural notes, Home Hints & Garden Gossip. Courses on War Time Gardening were provided for nine Beverley teachers who would then train school children.

By 1917 there were 41 acres of allotments in Beverley; Kitchen Lane, Captain Samman’s field, Morton Lane, Scarr’s Field, the Football field, Wellington Terrace, Norwood, Grovehill Road, Holme Church Lane corner. The following year the committee identified about 20 acres available for 300 more allotments in Pasture Terrace, Kitchen Lane, Cattle Market Lane (2 ½ acres), and Queensgate. A further 20 acres of Figham and 3 or 4 acres of Westwood on the Fishwick Mill site could be ploughed and cultivated. Allotment holders had their problems. They were accused of undercutting Market Gardeners and criticised for working on Good Friday, but protested they were doing “the best piece of good work possible”. The use of cooked rhubarb leaves instead of cabbage almost killed a woman. Gardens were invaded by rooks and pigeons, commonly believed to be fleeing the fighting in Europe. The East Riding War Agricultural Committee organised shoots to provide “good human food”. A letter in the Beverley Recorder suggested only shooting the foreign birds and not the native pigeons! There were problems with children ‘scrumping’ apples and one man complained about losing a third of his shallots to thieves.In 1917 the East Riding War Agricultural Committee decided 70,000 acres of grassland should be ploughed up, which would require 450 tractors. Farmers were unhappy about ploughing land which could feed cattle or sheep but was largely unsuitable for corn. In 1918 the Cultivation of Lands Order said that not less than 60% of arable land should be sown with the following crops for Harvest 1919 – wheat, barley, oats, rye, flax, potatoes or carrots. By mid 1918 the area under corn and potatoes in the East Riding increased by 90,000 acres and a good harvest was expected. Soldiers, women, and 40 German Prisoners of war, billeted in camps would get in the harvest. Horse racing had been stopped on the Westwood. Foxhunting was prohibited and hounds would be sent to the USA and returned after the war in the belief that tons of crops would be saved and men released for the forces. 50% of hounds were destroyed.

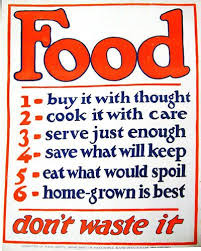

Despite appeals for people to cut down on food, potatoes, sugar, butter and margarine were in great demand and very scarce. Food rationing was introduced for the first time, in Britain, in February 1918. This started with sugar, and then restrictions on meat, butter, jam, and margarine. Cheese and tea were rationed locally. Ration coupons were issued to control rising food prices and share out limited food supplies fairly. Ration cards were issued and people registered with a local butchers or grocers. The weekly ration was set at 15 ounces of meat, five ounces of bacon and four ounces of butter or margarine. With rationing, food queues disappeared and everyone received a fair share. Prices kept high, but the threat of shortages was averted. Grocers were liable to be imprisoned if they imposed conditions on the sale of sugar, such as a requirement for other things to be bought at the same time. A greengrocer was fined 10/- for refusing to sell potatoes to people who weren’t his regular customers. Beverley tobacconists did good business before Christmas because of people sending cigarettes to the lads at the front. Tobacco went up from 6/5d to 8/2d per pound, a rise of 2d per ounce to the consumer. Matches went up from ½d to 1d. There was an increase of 2d in the shilling on luxuries. In February 1918 Free Demonstrations of Economic Cookery were held. The withdrawal of labour from food production and the difficulty of importing goods safely created tremendous food shortages. People were told to drink coffee instead of tea. Beverley Grocer, Richard Care, advised, “Drink less tea, use Care’s coffees and cocoa”, while Abrams’ shop sold “Coffee for Tea Drinkers. While tea is short we strongly advise the people of Beverley & District to Drink Abrams’ Coffee. Put plenty in and Make it Good. Don’t forget that pinch of salt”. Coal shortages meant everyone must conserve gas and electricity. Paper was in short supply so experiments to combine 25% of waste paper with sawdust, straw, oat husks, or potato stalks were all tried with varying results. Remnants of candle wax were used as floor polish. Fine ashes mixed with vinegar made a splendid metal polish. Restaurants and cafes could not serve meals between 9.30 p.m. and 5.30 a.m., potatoes could only be served on Fridays and meat was off the menu on two days a week so vegetarian sausages were introduced. No gas or electricity should be used in places of entertainment between 10.30 p.m. and 1 p.m. the following day. Shops had to close early in 1918 to conserve coal and gas stocks.

The Government set up 363 ‘National Kitchens’, including one in Hull, to feed people during World War One. These improved diets, cut down food waste and proved hugely popular. A bowl of soup, a joint of meat and a portion of side vegetables cost 6d – just over £1 in today’s money. Puddings, scones and cakes could be bought for as little as 1d (about 18p). These self-service restaurants, run by local workers and partly funded by government grants, offered simple meals at subsidised prices. A 1918 ‘Scarborough Post’ story about the national kitchen in Hull emphasised the ambition of the typical urban outlet: “The place has the appearance of being a prosperous confectionery and cafe business. The business done is enormous.”